Melting-point depression

- This article deals with melting/freezing point depression due to very small particle size. For depression due to the mixture of another compound, see freezing-point depression.

Melting-point depression is the phenomenon of reduction of the melting point of a material with reduction of its size. This phenomenon is very prominent in nanoscale materials, which melt at temperatures hundreds of degrees lower than bulk materials.

Introduction

The melting temperature of a bulk material is not dependent on its size. However, as the dimensions of a material decrease towards the atomic scale, the melting temperature scales with the material dimensions. The decrease in melting temperature can be on the order of tens to hundreds of degrees for metals with nanometer dimensions.[1][2][3][4]

Melting-point depression is most evident in nanowires, nanotubes and nanoparticles, which all melt at lower temperatures than bulk amounts of the same material. Changes in melting point occur because nanoscale materials have a much larger surface-to-volume ratio than bulk materials, drastically altering their thermodynamic and thermal properties.

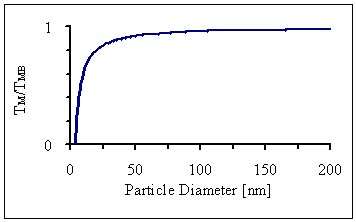

This article focuses on nanoparticles because researchers have compiled a large amount of size-dependent melting data for near spherical nanoparticles.[1][2][3][4] Nanoparticles are easiest to study due their ease of fabrication and simplified conditions for theoretical modeling. The melting temperature of a nanoparticle decreases sharply as the particle reaches critical diameter, usually < 50 nm for common engineering metals.[1][2][5] Figure 1 shows the shape of a typical melting curve for a metal nanoparticle as a function of its diameter.

Melting point depression is a very important issue for applications involving nanoparticles, as it decreases the functional range of the solid phase. Nanoparticles are currently used or proposed for prominent roles in catalyst, sensor, medicinal, optical, magnetic, thermal, electronic, and alternative energy applications.[6] Nanoparticles must be in the solid state to function at elevated temperatures in several of these applications.

Measurement techniques

Two techniques allow measurement of the melting point of nanoparticle. As described above, the electron beam of the transmission electron microscope (TEM) can be used to melt nanoparticles.[4][7] The melting temperature is estimated from the beam intensity, while changes in the diffraction conditions to indicate phase transition from solid to liquid. This method allows direct viewing of nanoparticles as they melt, making it possible to test and characterize samples with a wider distribution of particle sizes. The TEM limits the pressure range at which melting point depression can be tested.

More recently, researchers developed nanocalorimeters that directly measure the enthalpy and melting temperature of nanoparticles.[5] Nanocalorimeters provide the same data as bulk calorimeters, however additional calculations must account for the presence of the substrate supporting the particles. A narrow size distribution of nanoparticles is required since the procedure does not allow users to view the sample during the melting process. There is no way to characterize the exact size of melted particles during experiment.

History

Melting point depression was predicted in 1909 by Pawlow. [8] Takagi first observed melting point depression of several types of metal nanoparticles in 1954.[4] A variable intensity electron beam from a transmission electron microscope melted metal nanoparticles in early experiments. Diffraction patterns changed from characteristic crystalline patterns to liquid patterns as the small particles melted, allowing Takagi to estimate the melting temperature from the electron beam energy.

Physics

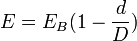

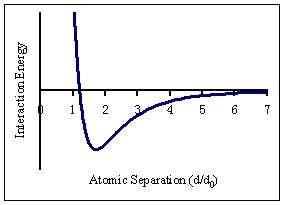

Nanoparticles have a much greater surface to volume ratio than bulk materials. The increased surface to volume ratio means surface atoms have a much greater effect on chemical and physical properties of a nanoparticle. Surface atoms bind in the solid phase with less cohesive energy because they have fewer neighboring atoms in close proximity compared to atoms in the bulk of the solid. Each chemical bond an atom shares with a neighboring atom provides cohesive energy, so atoms with fewer bonds and neighboring atoms have lower cohesive energy. The average cohesive energy per atom of a nanoparticle has been theoretically calculated as a function of particle size according to Equation 1.[9]

Where: D=nanoparticle size

- d=atomic size

- Eb=cohesive energy of bulk

As Equation 1 shows, the effective cohesive energy of a nanoparticle approaches that of the bulk material as the material extends beyond atomic size range (D>>d).

Atoms located at or near the surface of the nanoparticle have reduced cohesive energy due to a reduced number of cohesive bonds. An atom experiences an attractive force with all nearby atoms according to the Lennard-Jones potential. The Lennard-Jones pair-potential shown in Figure 2 models the cohesive energy between atoms as a function of separation distance.

The cohesive energy of an atom is directly related to the thermal energy required to free the atom from the solid. According to Lindemann’s criterion, the melting temperature of a material is proportional to its cohesive energy, av (TM=Cav).[10] Since atoms near the surface have fewer bonds and reduced cohesive energy, they require less energy to free from the solid phase. Melting point depression of high surface to volume ratio materials results from this effect. For the same reason, surfaces of bulk materials can melt at lower temperatures than the bulk material.[11]

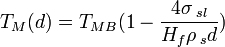

The theoretical size-dependent melting point of a material can be calculated through classical thermodynamic analysis. The result is the Gibbs–Thomson equation shown in Equation 2.[2]

Where: TMB=Bulk Melting temperature

- σsl=solid–liquid interface energy

- Hf=Bulk heat of fusion

- ρs=density of solid

- d=particle diameter

A normalized Gibbs–Thomson Equation for gold nanoparticles is plotted in Figure 1, and the shape of the curve is in general agreement with those obtained through experiment.[12]

Semiconductor/covalent nanoparticles

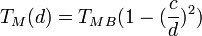

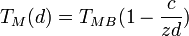

Equation 2 gives the general relation between the melting point of a metal nanoparticle and its diameter. However, recent work indicates the melting point of semiconductor and covalently bonded nanoparticles may have a different dependence on particle size.[13] The covalent character of the bonds changes the melting physics of these materials. Researchers have demonstrated that Equation 3 more accurately models melting point depression in covalently bonded materials.[13]

Where: TMB=Bulk Melting temperature

- c=materials constant

- d=particle diameter

Equation 3 indicates that melting point depression is less pronounced in covalent nanoparticles due to the quadratic nature of particle size dependence in the melting Equation.

Proposed mechanisms

The specific melting process for nanoparticles is currently unknown. The scientific community currently accepts several mechanisms as possible models of nanoparticle melting.[13] Each of the corresponding models effectively match experimental data for melting of nanoparticles. Three of the four models detailed below derive the melting temperature in a similar form using different approaches based on classical thermodynamics.

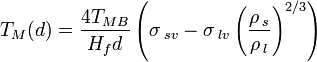

Liquid drop model

The liquid drop model (LDM) assumes that an entire nanoparticle transitions from solid to liquid at a single temperature.[10] This feature distinguishes the model, as the other models predict melting of the nanoparticle surface prior to the bulk atoms. If the LDM is true, a solid nanoparticle should function over a greater temperature range than other models predict. The LDM assumes that the surface atoms of a nanoparticle dominate the properties of all atoms in the particle. The cohesive energy of the particle is identical for all atoms in the nanoparticle.

The LDM represents the binding energy of a nanoparticles as function of the free energies of the volume and surface.[10] Equation 4 gives the normalized, size dependent melting temperature of a material according to the liquid-drop model.

Where: σsv=solid-vapor interface energy

- σlv=liquid-vapor interface energy

- Hf=Bulk heat of fusion

- ρs=density of solid

- ρl=density of liquid

- d=diameter of nanoparticle

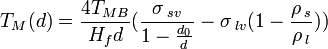

Liquid shell nucleation model

The liquid shell nucleation model (LSN) predicts that a surface layer of atoms melts prior to the bulk of the particle.[14] The melting temperature of a nanoparticle is a function of its radius of curvature according to the LSN. Large nanoparticles melt at greater temperatures as a result of their larger radius of curvature.

The model calculates melting conditions as a function of two competing order parameters using Landau potentials. One order parameter represents a solid nanoparticle, while the other represents the liquid phase. Each of the order parameters is a function of particle radius.

The parabolic Landau potentials for the liquid and solid phases are calculated at a given temperature, with the lesser Landau potential assumed to be the equilibrium state at any point in the particle. In the temperature range of surface melting, the results show that the Landau curve of the ordered state is favored near the center of the particle while the Landau curve of the disordered state is smaller near the surface of the particle.

The Landau curves intersect at a specific radius from the center of the particle. The distinct intersection of the potentials means the LSN predicts a sharp, unmoving interface between the solid and liquid phases at a given temperature. The exact thickness of the liquid layer at a given temperature is the equilibrium point between the competing Landau potentials.

Equation 5 gives the condition at which an entire nanoparticle melts according to the LSN model.[15]

Where: d0=atomic diameter

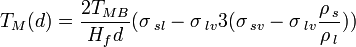

Liquid nucleation and growth model

The liquid nucleation and growth model (LNG) treats nanoparticle melting as a surface initiated process.[16] The surface melts initially, and the liquid-solid interface quickly advances through the entire nanoparticle. The LNG defines melting conditions through the Gibbs-Duhem relations, yielding a melting temperature function dependent on the interfacial energies between the solid and liquid phases, volumes and surface areas of each phase, and size of the nanoparticle. The model calculations show that the liquid phase forms at lower temperatures for smaller nanoparticles. Once the liquid phase forms, the free energy conditions quickly change and favor melting. Equation 6 gives the melting conditions for a spherical nanoparticle according to the LNG model.[15]

Bond-order-length-strength (BOLS) model

The bond-order-length-strength (BOLS) model employs an atomistic approach to explain melting point depression.[15] The model focuses on the cohesive energy of individual atoms rather than a classical thermodynamic approach. The BOLS model calculates the melting temperature for individual atoms from the sum of their cohesive bonds. As a result, the BOLS predicts the surface layers of a nanoparticle melt at lower temperatures than the bulk of the nanoparticle.

The BOLS mechanism states that if one bond breaks the remaining neighbouring ones become shorter and stronger. The cohesive energy, or the sum of bond energy, of the less coordinated atoms determines the thermal stability including melting, evaporating and other phase transition. The lowered CN changes the equilibrium bond length between atoms near the surface of the nanoparticle. The bonds relax towards equilibrium lengths, increasing the cohesive energy per bond between atoms, independent of the exact form of the specific interatomic potential. However, the integrated cohesive energy for surface atoms is much lower than bulk atoms due to the reduced coordination number and overall decrease in cohesive energy.

Using a core–shell configuration, the melting point depression of nanoparticles is dominated by the outermost two atomic layers yet atoms in the core interior remain their bulk nature.

The BOLS model and the core–shell structure have been applied to other size dependency of nanostructures such as the mechanical strength, chemical and thermal stability, lattice dynamics (optical and acoustic phonons), Photon emission and absorption, electronic colevel shift and work function modulation, magnetism at various temperatures, and dielectrics due to electron polarization etc. Reproduction of experimental observations in the above-mentioned size dependency has been realized. Quantitative information such as the energy level of an isolated atom and the vibration frequency of individual dimer has been obtained by matching the BOLS predictions to the measured size dependency.[16]

Particle shape

Nanoparticle shape impacts the melting point of a nanoparticle. Facets, edges and deviations from a perfect sphere all change the magnitude of melting point depression.[10] These shape changes affect the surface to volume ratio, which affects the cohesive energy and thermal properties of a nanostructure. Equation 7 gives a general shape corrected formula for the theoretical melting point of a nanoparticle based on its size and shape.[10]

Where: c=materials constant

- z=shape parameter of particle

The shape parameter is 1 for sphere and 3/2 for a very long wire, indicating that melting-point depression is suppressed in nanowires compared to nanoparticles. Past experimental data show that nanoscale tin platelets melt within a narrow range of 10 oC of the bulk melting temperature.[7] The melting point depression of these platelets was suppressed compared to spherical tin nanoparticles.[5]

Substrate

Several nanoparticle melting simulations theorize that the supporting substrate affects the extent of melting-point depression of a nanoparticle.[1][17] These models account for energetic interactions between the substrate materials. A free nanoparticle, as many theoretical models assume, has a different melting temperature (usually lower) than a supported particle due to the absence cohesive energy between the nanoparticle and substrate. However, measurement of the properties of a freestanding nanoparticle remains impossible, so the extent of the interactions cannot be verified through experiment. Ultimately, substrates currently support nanoparticles for all nanoparticle applications, so substrate/nanoparticle interactions are always present and must impact melting point depression.

Solubility

Within the size–pressure approximation, which considers the stress induced by the surface tension and the curvature of the particle, it was shown that the size of the particle affects the composition and temperature of a eutectic point (Fe-C[1]) the solubility of C in Fe[18] and Fe:Mo nanoclusters.[19] Reduced solubility can affect the catalytic properties of nanoparticles. In fact it has been shown that size-induced instability of Fe-C mixtures represents the thermodynamic limit for the thinnest nanotube that can be grown from Fe nanocatalysts.[18]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 A. Jiang, N. Awasthi, A. N. Kolmogorov, W. Setyawan, A. Borjesson, K. Bolton, A. R. Harutyunyan and S. Curtarolo (2007). "Theoretical study of the thermal behavior of free and alumina-supported Fe-C nanoparticles". Phys. Rev. B 75: 205426. arXiv:cond-mat/0612562. Bibcode:2007PhRvB..75t5426J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.75.205426.

- 1 2 3 4 J. Sun and S. L, Simon (2007). "The melting behavior of aluminum nanoparticles". Thermochimica Acta 463: 32. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2007.07.007.

- 1 2 A. F. Lopeandia and J. Rodriguez-Viejo (2007). "Size-dependent melting and supercooling of Ge nanoparticles embedded in a SiO2 thin film". Thermochimica Acta 461: 82. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2007.04.010.

- 1 2 3 4 M. Takagi (1954). "Electron-Diffraction Study of Liquid-Solid Transition of Thin Metal Films". J Phys. Soc. Jpn. 9: 359. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.9.359.

- 1 2 3 S. L. Lai, J. Y. Guo, V. Petrova, G. Rammath and L. H. Allen (1996). "Size-Dependent Melting Properties of Small Tin Particles: Nanocalorimetric Measurements". Phys. Rev. Lett. 77 (1): 99–102. Bibcode:1996PhRvL..77...99L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.99. PMID 10061781.

- ↑ G. G. Wildgoose, C. E. Banks and R. G. Compton (2005). "Metal Nanoparticles and Related Materials Supported on Carbon Nanotubes: Methods and Applications". Small 2 (2): 182–93. doi:10.1002/smll.200500324. PMID 17193018.

- 1 2 G. L. Allen, R. A. Bayles, W. W. Giles and W. A. Jesser (1986). "Small particle melting of pure metals". Thin Solid Films 144: 297. Bibcode:1986TSF...144..297A. doi:10.1016/0040-6090(86)90422-0.

- ↑ P. Pawlow. Z. Phys. Chemie, 65(1):545, 1909

- ↑ W. H. Qi and M. P. Wang (2002). "Size effect on the cohesive energy of nanoparticle". J. Mat. Sci. Lett. 21: 1743. doi:10.1023/A:1020904317133.

- 1 2 3 4 5 K. K. Nanda, S. N. Sahu and S. N. Behera (2002). "Liquid-drop model for the size-dependent melting of low-dimensional systems". Phys. Rev. A 66: 013208. Bibcode:2002PhRvA..66a3208N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.66.013208.

- ↑ J. W. M. Frenken and J. F. van der Veen (1985). "Observation of Surface Melting". Phys. Rev. Lett. 54 (2): 134–137. Bibcode:1985PhRvL..54..134F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.54.134. PMID 10031263.

- ↑ P. H. Buffat and J. P. Borrel (1976). "Size effect on the melting temperature of gold particles". Phys. Rev. A 13: 2287. Bibcode:1976PhRvA..13.2287B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.13.2287.

- 1 2 3 H. H. Farrell and C. D. Van Sicien (2007). "Binding energy, vapor pressure, and melting point of semiconductor nanoparticles". Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology B 25: 1441. Bibcode:2007JVSTB..25.1441F. doi:10.1116/1.2748415.

- ↑ H. Sakai (1996). "Surface-induced melting of small particles". Surf. Sci. 351: 285. Bibcode:1996SurSc.351..285S. doi:10.1016/0039-6028(95)01263-X.

- 1 2 3 C. Q. Sun, Y. Wang, B. K. Tay, S. Li, H. Huang and Y. B. Zhang (2002). "Correlation between the Melting Point of a Nanosolid and the Cohesive Energy of a Surface Atom". J. Phys. Chem. B 106: 10701. doi:10.1021/jp025868l.

- 1 2 C. Q. Sun (2007). "Size dependence of nanostructures: impact or bond order deficiency" (PDF). Progress in solid state chemistry 35: 1–159. doi:10.1016/j.progsolidstchem.2006.03.001.

- ↑ P. R. Couchman and W. A. Jesser (1977). "Thermodynamic theory of size dependence of melting temperature in metals". Nature 269 (5628): 481. Bibcode:1977Natur.269..481C. doi:10.1038/269481a0.

- 1 2 R. Harutyunyan, N. Awasthi, E. Mora, T. Tokune, A. Jiang, W. Setyawan, K. Bolton, and S. Curtarolo (2008). "Reduced carbon solubility in Fe nano-clusters and implications for the growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes". Phys. Rev. Lett. 100 (19): 195502. arXiv:0803.3191. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100s5502H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.195502. PMID 18518458.

- ↑ S. Curtarolo, N. Awasthi, W. Setyawan, A. Jiang, K. Bolton, and A. R. Harutyunyan (2008). "Influence of Mo on the Fe:Mo:C nano-catalyst thermodynamics for single-walled carbon nanotube growth". Phys. Rev. B 78: 054105. arXiv:0803.3206. Bibcode:2008PhRvB..78e4105C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.78.054105.