Measurement and signature intelligence

Measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT) is a technical branch of intelligence gathering, which serves to detect, track, identify or describe the signatures (distinctive characteristics) of fixed or dynamic target sources. This often includes radar intelligence, acoustic intelligence, nuclear intelligence, and chemical and biological intelligence.

MASINT may have aspects of intelligence analysis management, since certain aspects of MASINT, such as the analysis of electromagnetic radiation received by signals intelligence, are more of an analysis technique than a collection method. Some MASINT techniques require purpose-built sensors.

MASINT was recognized by the United States Department of Defense as an intelligence discipline in 1986.[1][2] MASINT is technically derived intelligence that—when collected, processed, and analyzed by dedicated MASINT systems—results in intelligence that detects and classifies targets, and identifies or describes signatures (distinctive characteristics) of fixed or dynamic target sources. In addition to MASINT, IMINT and HUMINT can subsequently be used to track or more precisely classify targets identified through the intelligence process. While traditional IMINT and SIGINT are not considered to be MASINT efforts, images and signals from other intelligence-gathering processes can be further examined through the MASINT discipline, such as determining the depth of buried assets in imagery gathered through the IMINT process.

William K. Moore described the discipline: "MASINT looks at every intelligence indicator with new eyes and makes available new indicators as well. It measures and identifies battlespace entities via multiple means that are difficult to spoof and it provides intelligence that confirms the more traditional sources, but is also robust enough to stand with spectrometry to differentiate between paint and foliage, or recognizing radar decoys because the signal lacks unintentional characteristics of the real radar system. At the same time, it can detect things that other sensors cannot sense, or sometimes it can be the first sensor to recognize a potentially critical datum."[3]

It can be difficult to draw a line between tactical sensors and strategic MASINT sensors. Indeed, the same sensor may be used tactically or strategically. In a tactical role, a submarine might use acoustic sensors—active and passive sonar—to close in on a target or get away from a pursuer. Those same passive sonars may be used by a submarine, operating stealthily in a foreign harbor, to characterize the signature of a new submarine type.

MASINT and technical intelligence (TECHINT) can overlap. A good distinction is that a technical intelligence analyst often has possession of a piece of enemy equipment, such as an artillery round, which can be evaluated in a laboratory. MASINT, even MASINT materials intelligence, has to infer things about an object that it can only sense remotely. MASINT electro-optical and radar sensors could determine the muzzle velocity of the shell. MASINT chemical and spectroscopic sensors could determine its propellant. The two disciplines are complementary: consider that the technical intelligence analyst may not have the artillery piece to fire the round on a test range, while the MASINT analyst has multispectral recordings of it being used in the field.

As with many intelligence disciplines, it can be a challenge to integrate the technologies into the active services, so they can be used by warfighters.[4]

Understanding "measurement" and "signature"

In the context of MASINT, "measurement" relates to the finite metric parameters of targets. "Signature" covers the distinctive features of phenomena, equipment, or objects as they are sensed by the collection instrument(s). The signature is used to recognize the phenomenon (the equipment or object) once its distinctive features are detected.[1] MASINT measurement searches for differences from known norms, and characterizes the signatures of new phenomena. For example, the first time a new rocket fuel exhaust is measured, it would be a deviation from a norm. When the properties of that exhaust are measured, such as its thermal energy, spectral analysis of its light (i.e., spectrometry), etc., those properties become a new signature in the MASINT database.

MASINT has been described as a "non-literal" discipline. It feeds on a target's unintended emissive byproducts, or "trails"—the spectral, chemical or RF emissions an object leaves behind. These trails form distinctive signatures, which can be exploited as reliable discriminators to characterize specific events or disclose hidden targets."[5]

While there are specialized MASINT sensors, much of the MASINT discipline involves analysis of information from other sensors. For example, a sensor may provide information on a radar beam, collected as part of Electronics intelligence (ELINT) gathering mission. Incidental characteristics recorded such as the "spillover" of the main beam (side lobes), or the interference its transmitter produces would come under MASINT.

MASINT specialists themselves struggle with providing simple explanations of their field.[6] One attempt calls it the “CSI” of the intelligence community,[6] in imitation of the television series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation. This emphasizes how MASINT depends on a great many sciences to interpret data.

Another possible definition calls it "astronomy except for the direction of view."[6] The allusion here is to observational astronomy being a set of techniques that do remote sensing looking away from the earth (contrasted with how MASINT employs remote sensing looking toward the earth). Astronomers make observations in multiple electromagnetic spectra, ranging through radio waves, infrared, visible, and ultraviolet light, into the X-ray spectrum and beyond. They correlate these multispectral observations and create hybrid, often “false-color” images to give a visual representation of wavelength and energy, but much of their detailed information is more likely a graph of such things as intensity and wavelength versus viewing angle.

National and multinational

There has been work on developing standardized MASINT terminology and architecture in NATO.[7] Other work addresses the disappointments of Non-Cooperative Target Recognition.[8] For this function, infrared beacons (infrared MASINT) proved disappointing, but millimeter-wave recognition shows more promise. Still, cooperative, network-based position exchange may be crucial in preventing fratricide. The bottom line is that MASINT cannot identify who is inside a tank or aircraft of interest.

Numerous countries produce their own antisubmarine warfare sensors, such as hydrophones, active sonar, magnetic anomaly detectors, and other hydrographic sensors that are frequently considered too "ordinary" to be called MASINT.

China

China is not reported to be pursuing the more specialized MASINT technologies,[9] although it does produce its antisubmarine sensors.

Germany

Following the first successful launch on December 19, 2006, about a year after the intended launch date, further satellites were launched at roughly six-month intervals, and the entire system of this five-satellite SAR Lupe synthetic aperture radar constellation achieved full operational readiness on 22 July 2008.[10]

Italy

Italy and France are cooperating on the deployment of the dual-use Orfeo civilian and military satellite system.[11]

Orfeo is a dual-use (civilian and military) earth observation satellite network developed jointly between France and Italy. Italy is developing the Cosmo-Skymed X-band polarimetric synthetic aperture radar, to fly on two of the satellites.

Russia

Russia does have nonimaging infrared satellites to detect missile launches.[12] Russia produces, of course, a wide range of antisubmarine warfare sensors.

United Kingdom

UK developed the first successful acoustic system, sound ranging to detect hostile artillery and anti-submarine acoustic detection in World War I. In the 1990s, an improved acoustic system for artillery location acoustic artillery location system was introduced, which complements Counter-battery radar.

United States

Within the US Intelligence Community the Directorate of MASINT and Technical Collections office of the Defense Intelligence Agency is the central agency for MASINT. This was formerly called the Central MASINT Office. For education and research, there is the Center for MASINT Studies and Research of the Air Force Institute of Technology.

Clearly, the National Reconnaissance Office and National Security Agency work in collecting MASINT, especially with military components. Other intelligence community organizations also have a collection role and possibly an analytic role. In 1962, the Central Intelligence Agency, Deputy Directorate for Research (now the Deputy Directorate for Science and Technology), formally took on ELINT and COMINT responsibilities.[13]

The consolidation of the ELINT program was one of the major goals of the reorganization. ... it is responsible for:CIA's Office of Research and Development was formed to stimulate research and innovation testing leading to the exploitation of non-agent intelligence collection methods. ... All non-agent technical collection systems will be considered by this office and those appropriate for field deployment will be so deployed. The Agency's missile detection system, Project [deleted] based on backscatter radar is an example. This office will also provide integrated systems analysis of all possible collection methods against the Soviet antiballistic missile program is an example.[13]

- Research, development, testing, and production of ELINT and COMINT collection equipment for all Agency operations.

- Technical operation and maintenance of CIA deployed non-agent ELINT systems.

- Training and maintenance of agent ELINT equipment

- Technical support to the Third Party Agreements.

- Data reduction of Agency-collected ELINT signals.

- ELINT support peculiar to the penetration problems associated with the Agent's reconnaissance program under NRO.

- Maintain a quick reaction capability for ELINT and COMINT equipment.

It is not clear where ELINT would end and MASINT would begin for some of these projects, but the role of both is potentially present. MASINT, in any event, was not formalized as a US-defined intelligence discipline until 1986.

MASINT from clandestinely placed sensors

CIA took on a more distinct MASINT responsibility in 1987.[14] The National Security Archive commented, "In 1987, Deputy Director for Science and Technology Evan Hineman established ... a new Office for Special Projects, concerned not with satellites, but with emplaced sensors—sensors that could be placed in a fixed location to collect signals intelligence or measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT) about a specific target. Such sensors had been used to monitor Chinese missile tests, Soviet laser activity, military movements, and foreign nuclear programs. The office was established to bring together scientists from the DS&T’s Office of SIGINT Operations, who designed such systems, with operators from the Directorate of Operations, who were responsible for transporting the devices to their clandestine locations and installing them.

The National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency plays a role in geophysical MASINT.

Multinational counterproliferation

All nuclear testing, of any level, was forbidden under the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) (which has not entered into force), but there is controversy over whether the preparatory commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) or the Treaty Organization itself will be able to detect sufficiently small events. It is possible to gain valuable data from a nuclear test that has an extremely low yield, useless as a weapon but sufficient to test weapons technology. CTBT does not recognize the threshold principle and assumes all tests are detectable.

The CTBTO runs an International Monitoring System (IMS) of MASINT sensors for verification, which include seismic, acoustic, and radionuclide techniques. See National technical means of verification for a discussion of the controversies surrounding the ability of the IMS to detect nuclear tests.

Military uses

Even though today's MASINT is often on the edge of technologies, many of them under high security classification, the techniques have a long history. Captains of warships, in the age of sail, used his eyes, and his ears, and sense of touch (a wetted finger raised to the breeze) to measure the characteristics of wind and wave. He used a mental library of signatures to decide what tactical course to follow based on weather. Medieval fortification engineers would put their ear to the ground to obtain acoustic measurements of possible digging to undermine their walls.

Acoustic and optical methods for locating hostile artillery go back to World War I. While these methods were replaced with radar for modern counter-battery fire, there is a resurgence of interest in acoustic gunfire locators against snipers and urban terrorists. Several warfighter application areas are listed below; also see Deeply Buried Structures.

Non-cooperative target recognition

MASINT could be of tactical use in "Non-Cooperative Target Recognition" (NCTR) so that, even with the failure of identification friend or foe (IFF) systems, friendly fire incidents could be prevented.(Ives)

Unattended ground sensors

Another strong need where MASINT may help is with unattended ground sensors (UGS).[15] During the Vietnam War, UGS did not provide the functionality desired in the McNamara Line and Operation Igloo White. They have improved considerably, but are still an additional capability for humans on the ground, not usually replacing people altogether.

In the U.S., much of the Igloo White technology came from Sandia National Laboratories, which subsequently designed the Mini Intrusion Detection System (MIDS) family, and the U.S. Marine Corps's AN/GSQ-261 Tactical Remote Sensor System (TRSS). Another major U.S. Army initiative was the Remotely Monitored Battlefield Sensor System (REMBASS), which it upgraded to Improved REMBASS (IREMBASS), and now is considering REMBASS II. The REMBASS generations, for example, increasingly intertwine interconnections of infrared MASINT, Magnetic MASINT, seismic MASINT, and acoustic MASINT.

The UK and Australia also are interested in UGS. Thales Defence Communications, a division of French Thales and formerly Racal, builds the Covert Local Area Sensor System for Intruder Classification (CLASSIC) for use in 35 countries, including 12 NATO members. Australia adopted the CLASSIC 2000 version, which, in turn, becomes part of the Australian Ninox system, which also includes Textron Systems’ Terrain Commander surveillance system. CLASSIC has two kinds of sensors: Optical Acoustic Satcom Integrated Sensor (OASIS) and Air Deliverable Acoustic Sensor (ADAS), as well as television cameras, thermal imagers, and low-light cameras.

ADAS sensors were in a U.S. program, Army Rapid Force Projection Initiative advanced concept technology demonstration (ACTD), using OASIS acoustic sensors and central processing, but not the electro-optical component. ADAS sensors are emplaced in clusters of three or four, for increased detection capability and for triangulation. Textron says that the ADAS acoustic sensors can track fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters, and UAVs as well as traditional ground threats.

ACTD added Remote Miniature Weather Station (RMWS), from System Innovations. These RMWS measure temperature, humidity, wind direction and speed, visibility and barometric pressure, which can then be sent over commercial or military satellite links.

Employing UGS is especially challenging in urban areas, where there is a great deal more background energy and a need to separate important measurements from them. Acoustic sensors will need to distinguish vehicles and aircraft from footsteps (unless personnel detection is a goal), and things such as construction blasting. They will need to discriminate among simultaneous targets. Infrared imaging, for the urban environment, will need smaller pixels. If either the targets or the sensor is moving, micro-electromechanical accelerometers will be needed.

Research programs: Smart Dust and WolfPack

Still more of an UGS research program, under DARPA, is Smart Dust, which is a program for developing massively parallel networks of hundreds or thousand "motes," on the order of 1 mm3.

Another DARPA program is WolfPack, a ground-based electronic warfare system. WolfPack is made up of a "pack" of "wolves." Wolves are distributed electronic detection nodes with location and classification capability, which may use radiofrequency MASINT techniques along with ELINT methods. The wolves could be hand, artillery, or airdrop delivered. WolfPack may fit into an Air Force program for a new subdiscipline of counter-ESM, as well as Distributed Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (DSEAD), an enhancement on SEAD. If the Wolves are colocated with jammers or other ECM, and they are very close to the target, they will not need much power to mask the signatures of friendly ground forces, in frequencies used for communications or local detection. DSEAD works in a similar way, but at radar frequencies. It may be interesting to compare this counter-ELINT discipline with ECCM.

Disciplines

| Intelligence cycle management |

|---|

| Intelligence collection management |

| MASINT |

MASINT is made up of six major disciplines, but the disciplines overlap and intertwine. They interact with the more traditional intelligence disciplines of HUMINT, IMINT, and SIGINT. To be more confusing, while MASINT is highly technical and is called such, TECHINT is another discipline, dealing with such things as the analysis of captured equipment.

An example of the interaction is "imagery-defined MASINT (IDM)". In IDM, a MASINT application would measure the image, pixel by pixel, and try to identify the physical materials, or types of energy, that are responsible for pixels or groups of pixels: signatures. When the signatures are then correlated to precise geography, or details of an object, the combined information becomes something greater than the whole of its IMINT and MASINT parts.

As with many branches of MASINT, specific techniques may overlap with the six major conceptual disciplines of MASINT defined by the Center for MASINT Studies and Research, which divides MASINT into Electro-optical, Nuclear, Geophysical, Radar, Materials, and Radiofrequency disciplines.[16]

A different set of disciplines comes from DIA:[17]

- nuclear, chemical, and biological features;

- emitted energy (e.g., nuclear, thermal, and electromagnetic);

- reflected (re-radiated) energy (e.g., radio frequency, light, and sound);

- mechanical sound (e.g., engine, propeller, or machinery noise);

- magnetic properties (e.g., magnetic flux and anomalies);

- motion (e.g., flight, vibration, or movement); and

- material composition.

The two sets are not mutually exclusive, and it is entirely possible that as this newly recognized discipline emerges, a new and more widely accepted set will evolve. For example, the DIA list considers vibration. In the Center for MASINT Studies and Research list, mechanical vibrations, of different sorts, can be measured by geophysical acoustic, electro-optical laser, or radar sensors.

Basic interaction of energy sources with targets

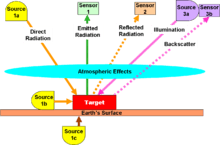

Remote sensing depends on the interaction of a source of energy with a target, and energy measured from the target.[18] In the "Remote Sensing" diagram, Source 1a is an independent natural source such as the Sun. Source 1b is a source, perhaps manmade, that illuminates the target, such as a searchlight or ground radar transmitter. Source 1c is a natural source, such as the heat of the Earth, with which the Target interferes.

The Target itself may produce emitted radiation, such as the glow of a red-hot object, which Sensor 2 measures. Alternatively, Sensor 1 might measure, as reflected radiation, the interaction of the Target with Source 1a, as in conventional sunlit photography. If the energy comes from Source 1b, Sensor 1 is doing the equivalent of photography by flash.

Source 3a is under the observer's control, such as a radar transmitter, and Sensor 3b can be tightly coupled to Source 3. An example of coupling might be that Sensor 3 will only look for backscatter radiation after the speed-of-light delay from Source 3a to the target and back to the position of Sensor 3b. Such waiting for a signal at a certain time, with radar, would be an example of electronic counter-countermeasures (ECCM), so that a signal jamming aircraft closer to Sensor 3b would be ignored.

A bistatic remote sensing system would separate source 3a from sensor 3b; a multistatic system could have multiple pairs of coupled sources and sensors, or an uneven ratio of sources and sensors as long as all are correlated. It is well known that bistatic and multistatic radar are a potential means of defeating low-radar-observability aircraft. It is also a requirement, from operations personnel concerned with shallow water[19] operations.

Techniques such as synthetic aperture have source 3a and sensor 3b colocated, but the source-sensor array takes multiple measurements over time, giving the effect of physical separation of source and sensor.

Any of the illuminations of the target (i.e., Source 1a, 1b, or 3a), and the returning radiation, can be affected by the atmosphere, or other natural phenomena such as the ocean, between source and target, or between target and sensor.

Observe that the atmosphere comes between the radiation source and the target, and between the target and the sensor. Depending on the type of radiation and sensor in use, the atmosphere can have little interfering effect, or have a tremendous effect requiring extensive engineering to overcome.

First, the atmosphere may absorb part of the energy passing through it. This is bad enough for sensing if all wavelengths are affected evenly, but it becomes much more complex when the radiation is of multiple wavelengths, and the attenuation differs among wavelengths.

Second, the atmosphere may cause an otherwise tightly collimated energy beam to spread.

Classes of sensor

Sensing systems have five major subcomponents:

- Signal collectors, which concentrate the energy, as with a telescope lens, or a radar antenna that focuses the energy at a detector

- Signal detectors, such as charge-coupled devices for light or a radar receiver

- Signal processing, which may remove artifacts from single images, or compute a synthetic image from multiple views

- Recording mechanism

- Recording return mechanisms, such as digital telemetry from satellites or aircraft, ejection systems for recorded media, or physical return of a sensor carrier with the recordings aboard.

MASINT sensors may be framing or scanning or synthetic. A framing sensor, such as a conventional camera, records the received radiation as a single object. Scanning systems use a detector that moves across the field of radiation to create a raster or more complex object. Synthetic systems combine multiple objects into a single one.

Sensors may be passive or coupled to an active source (i.e., "active sensor"). Passive sensors receive radiation from the target, either from the energy the target emits, or from other sources not synchronized with the sensor.

Most MASINT sensors will create digital recordings or transmissions, but specific cases might use film recording, analog recording or transmissions, or even more specialized means of capturing information.

Passive sensing

Figure "Remote Sensing Geometry" illustrates several key aspects of a scanning sensor.

The instantaneous field of view (IFOV) is the area from which radiation currently impinges on the detector. The swath width is the distance, centered on the sensor path, from which signal will be captured in a single scan. Swath width is a function of the angular field of view (AFOV) of the scanning system. Most scanning sensors have an array of detectors such that the IFOV is the angle subtended by each detector and the AFOV is the total angle subtended by the array.

Push broom sensors either have a sufficiently large IFOV, or the scan moves fast enough with respect to the forward speed of the sensor platform, that an entire swath width is recorded without movement artifacts. These sensors are also known as survey or wide field devices, comparable to wide angle lenses on conventional cameras.

Whisk broom or spotlight sensors have the effect of stopping the scan, and focusing the detector on one part of the swath, typically capturing greater detail in that area. This is also called a close look scanner, comparable to a telephoto lens on a camera.

Passive sensors can capture information for which there is no way to generate man-made radiation, such as gravity. Geodetic passive sensors can provide detailed information on the geology or hydrology of the earth.

Active sensors

Active sensors are conceptually of two types, imaging and non-imaging. Especially when combining classes of sensor, such as MASINT and IMINT, it can be hard to define if a given MASINT sensor is imaging or not. In general, however, MASINT measurements are mapped to pixels of a clearly imaging system, or to geospatial coordinates known precisely to the MASINT sensor-carrying platform.

In MASINT, the active signal source can be anywhere in the electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to X-rays, limited only by the propagation of the signal from the source. X-ray sources, for example, must be in very close proximity to the target, while lasers can illuminate a target from a high satellite orbit. While this discussion has emphasized the electromagnetic spectrum, there are also both active (e.g., sonar) and passive (e.g., hydrophone and microbarograph) acoustic sensors.

Quality of sensing

Several factors make up the quality of a given sensor's information acquisition, but assessing quality can become quite complex when the end product combines the data from multiple sensors. Several factors, however, are commonly used to characterize the basic quality of a single sensing system.

- Spatial resolution defines the correspondence between each recorded pixel and the square real-world area that the pixel covers.

- Spectral resolution is the number of discrete frequency (or equivalent) bands recorded in an individual pixel. Remember that relatively coarse spectral resolution from one sensor, such as the spectroscopic analyzer that reveals a "bush" is painted plaster, may greatly enhance the ultimate value of a different sensor with finer spectral resolution.

- Radiometric resolution is the number of levels of energy recorded, per pixel, in each spectral band.

- Temporal resolution describes the intervals at which the target is sensed. This is meaningful only in synthetic imaging, comparison over a longer time base, or in producing full-motion imagery.

- Geospatial resolution is the quality of mapping pixels, especially in multiple passes, to known geographic or other stable references.

Cueing

Cross-cueing is the passing of detection, geolocation and targeting information to another sensor without human intervention.[20] In a system of sensors, each sensor must understand which other sensors complement it. Typically, some sensors are sensitive (i.e., with a low incidence of false negatives) while others have a low incidence of false positives. A fast sensitive sensor that covers a large area, such as SIGINT or acoustic, can pass coordinates of a target of interest to a sensitive narrowband RF spectrum analyzer for ELINT or a hyperspectral electro-optical sensor. Putting sensitive and selective, or otherwise complementary sensors, into the same reconnaissance or surveillance system enhances the capabilities of the entire system, as in the Rocket Launch Spotter.

When combining sensors, however, even a quite coarse sensor of one type can cause a huge increase in the value of another, more fine-grained sensor. For example, a highly precise visible-light camera can create an accurate representation of a tree and its foliage. A coarse spectral analyzer in the visible light spectrum, however, can reveal that the green leaves are painted plastic, and the "tree" is camouflaging something else. Once the fact of camouflage is determined, a next step might be to use imaging radar or some other sensing system that will not be confused by the paint.

Cueing, however, is a step before automatic target recognition, which requires both extensive signature libraries and reliable matching to it.

References

- 1 2 Interagency OPSEC Support Staff (IOSS) (May 1996), "Section 2, Intelligence Collection Activities and Disciplines", Operations Security Intelligence Threat Handbook, retrieved 2007-10-03

- ↑ US Army (May 2004). "Chapter 9: Measurement and Signals Intelligence". Field Manual 2-0, Intelligence. Department of the Army. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ↑ William K. Moore (January–March 2003). "MASINT: new eyes in the battlespace". Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ↑ Ives, John W. (9 April 2002). "Army Vision 2010: Integrating Measurement and Signature Intelligence". US Army War College. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ↑ Lum, Zachary (August 1998). "The measure of MASINT". Journal of Electronic Defense. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- 1 2 3 Center for MASINT Studies and Research. "Toward a Better Definition [of MASINT]". Air Force Institute of Technology. BetterDef. Archived from the original on April 26, 2008. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ↑ Meiners, Kevin (22 March 2005). "Net-Centric ISR" (PDF). National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA). Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ↑ Bialos, Jeffrey P.; Stuart L. Koehl. "The NATO Response Force: Facilitating Coalition Warfare Through Technology Transfer and Sharing" (PDF). Center for Transatlantic Relations and Funded by the Center for Technology and National Security Policy. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 11, 2006. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ↑ Lewis, James A. (January 2004). "China as a Military Space Competitor" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ↑ Spaceflight now—Radar reconnaissance spacecraft launched

- ↑ Deagel.com (October 19, 2007), Successful Launch Second German Sar-Lupe Observation Satellite, Deagel 2007, retrieved 2007-10-19

- ↑ Interagency OPSEC Support Staff (May 1996). "Operations Security Intelligence Threat Handbook, Section 3, Adversary Foreign Intelligence Operations".

- 1 2 Central Intelligence Agency (1962), Deputy Director for Research (PDF), CIA-DDR, retrieved 2007-10-07

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency (1965), Organization chart, mission and functions of the Office of Special Projects (PDF), retrieved 2007-10-07

- ↑ Mark Hewish (June 2001). "Reformatting Fighter Tactics" (PDF). Jane's International Defence Review. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Center for MASINT Studies and Research, Center for MASINT Studies and Research, Air Force Institute of Technology, CMSR, archived from the original on July 7, 2007, retrieved 2007-10-03

- ↑ Rau, Russell A, Assistant Auditor General, Defense Intelligence Agency (June 30, 1997), Evaluation Report on Measurement and Signature Intelligence, Rau 1997, retrieved 2007-10-21

- ↑ Meaden, Geoffery J.; Kapetsky, James M. (1991), Geographical information systems and remote sensing in inland fisheries and aquaculture. Chapter 4: Remote Sensing as a Data Source (– Scholar search), Meaden1991, retrieved 2007-10-15

- ↑ National Academy of Sciences Commission on Geosciences, Environment and Resources (April 29 – May 2, 1991). "Symposium on Naval Warfare and Coastal Oceanography". NASCGER-91. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Bergman, Steven M. (December 1996). "The Utility of Hyperspectral Data in Detecting and Discriminating Actual and Decoy Target Vehicles" (PDF). US Naval Postgraduate School. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

External links

- ATIA—Advanced Technical Intelligence Association (formerly MASINT Association)

- ATIC—Advanced Technical Intelligence Center for Human Capital Development

- CMSR—Center for MASINT Studies and Research

- NCMR—National Consortium for MASINT Research

- The Intelligence Community in the 21st Century

- "A Tale of Two Airplanes" by Kingdon R. "King" Hawes, Lt Col, USAF (Ret.)

- Measurement and signature intelligence Citizendium article