McConnel & Kennedy Mills

| |

| Location | Ancoats |

|---|---|

| [1][2] | |

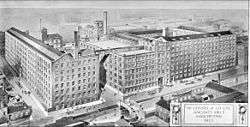

McConnel & Kennedy Mills are a group of cotton mills on Redhill Street in Ancoats, Manchester, England. With the adjoining Murrays' Mills, they form a nationally important group.

The complex consists of six mills, Old Mill built in 1797, Long Mill from 1801 and Sedgewick Mill built between 1818–1820. A further phase of building in the early 20th century added Sedgewick New Mill in 1912, Royal Mill, originally the New Old Mill built in 1912 but renamed in 1942, and Paragon Mill also built in 1912. Paragon Mill at eight storeys high was the world's tallest cast iron structure when it was built.

History

The first phase of mills in Manchester such as Garratt Mill (1760), Holt's Mills, Meredith's Factory (1760), Gaythorn Mill (1788), Wood Mill (1788) and Knott Mill (1792) were water-powered, taking their power from the River Medlock.[3] Salvin's ran a room and power mill (1780) on the Shooters Brook in Ancoats, and here the partnership of Sandford, McConnel and Kennedy was formed. Salvin's factory failed to get enough power from Shooters Brook, so he improved the head of water with a Savery type steam-powered pump. In 1793 John Kennedy directly connected a spinning mule to a steam engine. On 2 March 1795 the partnership was terminated, McConnel and Kennedy moved to other premises in Derby Street. Kennedy manufactured and sold spinning mules until 1801.[4]

The next phase of mills was powered by Boulton and Watt double-acting beam engines. Though flowing water was no longer required, a considerable amount of water was needed for the engines' condensors which was provided by a mill lodge, canal or brook. The first Boulton and Watt engine in Manchester was bought by Drinkwater's Mill in Piccadilly in 1789, and installed by the Birmingham company's prizefighting engineer, Isaac Perrins.[5]

James McConnel, served an apprenticeship with William Cannan in Chowbent, and moved to Manchester in 1788 to work for Alexander Egelsom a weft and twist dealer with a cotton spinning establishment on Newton Street, Ancoats. The Murrays probably used the same building. In 1791 McConnel joined the partnership with Sandford and Kennedy. By 1797 McConnel and Kennedy had built a mill with steam powered spinning mules. This was Old Mill, powered by a 16 hp Boulton and Watt engine in an external engine and boiler house. The seven-storey mill was 16 bays long and 4 bays deep and had a cupola on the roof.[6]

Between 1801 and 1803, Long Mill was built, it was eight storeys high, 30 bays long by 4 bays deep, its 45 hp Boulton and Watt engine was placed in an internal engine house on the south side of the mill but the boilers were external. A tunnel and a bridge connected it to Old Mill. The Green Dragon public house on the corner of the plot, was left in situ. In 1809, a gas making plant was built on the site, and Long Mill became one of the first gas-lit mills. There were six gasometers and 1500 burners were fed by a 19mm pipe.[7]

Colonel Sedgewick sold adjacent land to McConnel & Kennedy in 1817 and the four blocks of Sedgewick Mill were erected between 1818 and 1820. The largest, facing Redhill Street (Union Street), was eight storeys high and 17 bays long. The blocks were of fireproof construction. The mill's main drive shaft ran in a tunnel under the ground floor from the internal engine house which contained a 54 hp Boulton and Watt beam engine with a 24 feet (7.3 m) flywheel. Sir William Fairbairn and James Lillie, designed and installed the shafting, which was unusual as the wings of the mill were offset at 15 degrees to the right angle. The main drive shaft powered a vertical shaft in each bay that ran to each floor. The company was the largest employer in Manchester at the time. John Kennedy retired in 1826, and the firm traded as McConnel & McConnel Co.[8]

Alexis de Tocqueville, described Redhill Street Mill in 1835 as "... a place where some 1500 workers, labouring 69 hours a week, with an average wage of 11 shillings, and where three-quarters of the workers are women and children". During the Cotton Famine, the company had obtained rights to Heilmann's combing machine.

As the century progressed, bigger and bigger machinery was used. Fairbairn and Lillie were employed to modify the structure of the mills in the mid-1860s. This involved replacing the old cast iron columns with new ones, each floor used a different technique.

Sedgewick New Mill, was an unusually narrow five-storey L shaped mill by A. H. Stott, designed for doubling sewing thread. It was Stott's second commission and neither party were satisfied with the result.[9] McConnel became part of the Fine Spinners' and Doublers' Association Limited in 1898. Paragon Mill and New Old Mill were built in the Edwardian Baroque style by H. S. Porter using Accrington brick and terracotta. They had cast iron columns supporting transverse steel beams and reinforced concrete floors. Initially they were built with five-storeys and nine bays but a sixth storey was added later. The machinery was electrically driven and a new electricity substation was built in 1915. At the same time, Sedgewick New Mill and Long Mill were virtually rebuilt to take heavier equipment (usually this meant ring spinning frames).

The mills were visited by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1942. New Old Mill was renamed Royal Mill, it was extended, and cut Cotton Street with a new entrance arch claiming Royal Mill had been first built in 1797.[10]

Spinning ceases

Spinning ceased in 1959, and the frames were sold. The buildings were bought by Leslie Fink who let out the space. The Long Mill was rented by the Flatley Drying Company, manufacturers of the Flatley clothes dryer invented by Andrew J. Flatley. In February 1959, the mill burned down and the site was redeveloped in 2001.[11]

References

- ↑ Manchester 2000

- ↑ Williams & Farnie 1992, p. 164

- ↑ Miller & Wild 2007, pp. 21, 27

- ↑ Miller & Wild 2007, p. 36

- ↑ Musson, A. E.; Robinson, E. (June 1960). "The Origins of Engineering in Lancashire". The Journal of Economic History (Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association) 20 (2): 224–225. JSTOR 2114855.

- ↑ Miller & Wild 2007, p. 50

- ↑ Miller & Wild 2007, p. 51

- ↑ Miller & Wild 2007, p. 53

- ↑ Miller & Wild 2007, p. 54

- ↑ Miller & Wild 2007, p. 55

- ↑ Miller & Wild 2007, p. 56

Bibliography

- Ashmore, Owen (1982). The Industrial Archaeology of North-west England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0820-4.

- Williams, Mike; Farnie, D. A. (1992). Cotton Mills in Greater Manchester. Preston: Carnegie Publishing. ISBN 0-948789-89-1.

- Miller, Ian; Wild, Chris (2007), A & G Murray and the Cotton Mills of Ancoats, Lancaster: Oxford Archaeology North, ISBN 978-0-904220-46-9 Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - "Cotton Mills in Manchester and Salford 1891". Graces Guides. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

External links

Coordinates: 53°29′01″N 2°13′39″W / 53.483612°N 2.22744°W