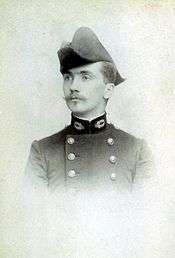

Maximilien Marie de Ficquelmont

| Charles-François-Maximilien Marie de Ficquelmont | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1 January 1819 Hôtel d'Angoulême Lamoignon, Paris, France |

| Died |

27 April 1891 (aged 72) Boulevard Saint-Germain, Paris, France |

| Residence | Paris, France |

| Citizenship | French |

| Nationality | French |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Alma mater | École Polytechnique |

| Doctoral advisor | Auguste Comte |

| Known for | imaginary number i |

Charles-François-Maximilien Marie de Ficquelmont (1819 − 1891) was a French mathematician, historian of mathematics and military officer, famous for resolving one of the most difficult problem of equational mathematics by inventing the imaginary number i.[1]

Biography

Count Charles-François-Maximilien Marie de Ficquelmont was born at the Hôtel Lamoignon in Paris on January 1, 1819, the son of a branch of a preeminent family of senior nobility. His father was a high-ranking military officer in Napoleon's Grande Armée, and Ficquelmont was expected to follow in his father's steps as a student at the prestigious École Polytechnique. He graduated from the Polytechnique in 1838 and went on to attend the École d'application de l'artillerie et du génie in Metz as an officer student in artillery. While an officer in training in Metz, he discovered a key element of solid mechanics as he found out how solid matters are moving.

In 1841, he was made a lieutenant-major, but, more attracted by the field of mathematics, he chose to resign from the army and move back to Paris. Close to the positivist movements, Ficquelmont began to spend time with his former professor philosopher Auguste Comte, who soon became his mentor.[2] In 1844, Ficquelmont introduced him to his sister, countess Clotilde de Vaux. Comte fell passionately in love with her, a feeling that she did not reciprocate,[3] and the one-sided affair ended when Clotilde suddenly died of tuberculosis a year later. Following Clotilde's death in 1846, Ficquelmont and Comte grow apart while Comte dedicated himself to reorganising his previous philosophical system into a new positivist secular religion inspired by Clotilde's moral values:[4] the Positivist Church or Religion of Humanity.

In 1862, backed by the famous mathematicians Joseph Liouville and General Jean-Victor Poncelet, Ficquelmont was appointed professor of Mechanics. In 1875, he was appointed head of admissions at the École Polytechnique. Besides his academic achievements at the Polytechnique, Ficquelmont developed a new theory of transcendental numbers that led him to resolve one of the most difficult problems of equational mathematics by inventing the imaginary number i.[5] Ficquelmont also became well known for his work as an historian of mathematics.[6]

Growing old, Ficquelmont entered politics during the Third Republic and became mayor of Châtillon. In 1890, he retired from the Polytechnique and died a year later.

Honors

Maximilien Marie de Ficquelmont was made chevalier (1876), then officer (12 juillet 1880), of the Légion d’honneur,[7] France's highest honor.

Works

As a mathematician he "resolved one of most difficult problem of equational mathematics".[8] As a historian of mathematics, he published a 12-volume encyclopedia, History of the Mathematics,[9] which was divided into two parts: Théorie des fonctions de variables imaginaires (tomes I à III, Gauthier-Villars, 1874–1876, 3 vol.) and Histoire des sciences mathématiques et physiques (tomes I à XII, Gauthier-Villars, 1883–1888, 12 vol.)

Family

As a consequence of the French Revolution, the Ficquelmont family spread across Europe. Part of the family remained in France where Maximilien – named after his grandfather count Maximilien-Chrétien de Ficquelmont (1746-1819) – was born the second child and first son of countess Henriette-Philippine and commander Joseph-Simon Marie de Ficquelmont, grand officier of the Légion d'honneur.[7] But other members settled in Naples, Hungary, England but more importantly:

- – the Empire of Austria, where Maximilien's uncle, Reischgraf Charles-Louis de Ficquelmont became Minister-President;

- – the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, where one of Maximilien's grand-uncles, count Antoine-Charles de Ficquelmont (1753-1833), recreated the title Count de Ficquelmont within the Dutch nobility[10] (July 16, 1822).

Ficquelmont had one elder sister, the famous positivist muse Clotilde de Vaux, and one younger brother, count Léonard Marie de Ficquelmont (1820–1860), chevalier[7] of the Légion d'honneur, who was also a military officer trained at the École Polytechnique and who died without issue at the Battle of Palikao. The siblings had only one cousin: Elisabeth-Alexandrine de Ficquelmont, Countess de Ficquelmont by birth and Princess Clary und Aldringen by marriage..

On January 20, 1844, Ficquelmont married countess Philiberte Félicité Aniel with whom he had a son, Charles-Paul-Augustin-Maximilien-Léon Marie de Ficquelmont (1845 – 1886), chevalier of the Légion d'honneur,[11] who graduated from the École Polytechnique to become a French military officer. He served as Chief of Defence of the artillery and died during the Franco-Chinese War, having had issue.

Sources and references

- ↑ Théorie des fonctions de variables imaginaires, tomes I à III, Gauthier-Villars, 1874–1876, 3 vol.

- ↑ Henri Gouhier, La vie d'Auguste Comte (1931, rééd. 1997), libr. phil. Vrin, Coll. bibl. des textes Phil

- ↑ André Thérive, Clotilde de Vaux ou La déesse morte, Albin Michel, 1957

- ↑ Auguste Comte, Système de politique positive (1851–1854)

- ↑ 'Théorie des fonctions de variables imaginaires, tomes I à III, Gauthier-Villars, 1874–1876, 3 vol.

- ↑ Histoire des sciences mathématiques et physiques, tomes I à XII, Gauthier-Villars, 1883–1888, 12 vol

- 1 2 3 Chancellerie of the Légion d'honneur

- ↑ « les problèmes les plus élevés de l'analyse transcendantale »in La Nature n°936 – 9 mai 1891

- ↑ Maximilien Marie, Histoire des sciences mathématiques et physiques (volume 3 : de Viète à Descartes), 1884

- ↑ the title became Belgian after 1830

- ↑ 18 janvier 1881

|