Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, known as Matthew of Paris (Latin: Matthæus Parisiensis, lit. "Matthew the Parisian";[1] c. 1200 – 1259), was a Benedictine monk, English chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey in Hertfordshire. He wrote a number of works, mostly historical, which he scribed and illuminated himself, typically in drawings partly coloured with watercolour washes, sometimes called "tinted drawings". Some were written in Latin, some in Anglo-Norman or French verse.

His Chronica Majora is an oft-cited source, though modern historians recognise that Paris was not always reliable. He tended to glorify Emperor Frederick II and denigrate the Pope.[2] However, in his Historia Anglorum, Paris displays a highly negative view of Frederick, going as far as to describe him as a "tyrant" who "committed disgraceful crimes".[3]

Life and work

In spite of his surname and knowledge of the French language, Paris was of English birth, and is believed by some chroniclers to be of the Paris family of Hildersham, Cambridgeshire.[4] He may have studied at Paris in his youth after early education at St Albans School. The first we know of Matthew Paris (from his own writings) is that he was admitted as a monk to St Albans in 1217. It is on the assumption that he was in his teens on admission that his birth date is estimated; some scholars suspect he may have been ten years or more older; many monks only entered monastic life after pursuing a career in the world outside. He was clearly at ease with the nobility and even royalty, which may indicate that he came from a family of some status, although it also seems an indication of his personality. His life was mainly spent in this religious house. In 1248, Paris was sent to Norway as the bearer of a message from Louis IX to Haakon IV; he made himself so agreeable to the Norwegian sovereign that he was invited to superintend the reformation of the Benedictine Nidarholm Abbey outside Trondheim.

Apart from these missions, his known activities were devoted to the composition of history, a pursuit for which the monks of St Albans had long been famous. After admission to the order in 1217, he inherited the mantle of Roger of Wendover, the abbey's official recorder of events, in 1236. Paris revised Roger's work, adding new material to cover his own tenure. This Chronica Majora is an important historical source document, especially for the period between 1235 and 1259. Equally interesting are the illustrations Paris created for his work.

The Dublin MS (see below) contains interesting notes, which shed light on Paris's involvement in other manuscripts, and on the way his own were used. They are in French and in his handwriting:

- "If you please you can keep this book till Easter"

- "G, please send to the Lady Countess of Arundel, Isabel, that she is to send you the book about St Thomas the Martyr and St Edward which I copied (translated?) and illustrated, and which the Lady Countess of Cornwall may keep until Whitsuntide"

- some verses

- "In the Countess of Winchester's book let there be a pair of images on each page thus": (verses follow describing thirteen saints)

– it is presumed the last relates to Paris acting as commissioning agent and iconographical consultant for the Countess with another artist.

The lending of his manuscripts to aristocratic households, apparently for periods of weeks or months at a time, suggests why he made several different illustrated versions of his Chronicle.

Manuscripts by Matthew Paris

Paris's manuscripts mostly contain more than one text, and often begin with a rather random assortment of prefatory full-page miniatures. Some have survived incomplete, and the various elements now bound together may not have been intended to be so by Paris. Unless stated otherwise, all were given by Paris to his monastery (from some inscriptions it seems they were regarded as his property to dispose of). The monastic libraries were broken up at the Dissolution. These MS seem to have been appreciated, and were quickly collected by bibliophiles.. Many of his manuscripts in the British Library are from the Cotton Library.

- Chronica Majora. Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Mss 26 and 16, 362 x 244/248 mm. ff 141 + 281, composed 1240–53. His major historical work (see below), but less heavily illustrated per page than others . These two volumes contain annals from the creation of the world up to the year 1253. The content up to 1234 or 1235 is based in the main on Roger of Wendover's Flores Historiarum, with additions; after that date the material is Paris's own, and written in his own hand from the annal for 1213 onward. There are 100 marginal drawings (25 + 75), some fragmentary maps and an itinerary, and full-page drawings of William I and the Elephant with Keeper. MS 16 has very recently had all prefatory matter re-bound separately.

.

.

- A continuation of the Chronica, from 1254 until Paris's death in 1259, is bound with the Historia Anglorum in the British Library volume below. An unillustrated copy of the material from 1189 to 1250, with much of his sharper commentary about Henry III toned down or removed, was supervised by Paris himself and now exists as British Library Cotton MS Nero D V, fol. 162–393.[5]

- Flores Historiarum. Chetham's Hospital and Library, Manchester, MS 6712. Only part of the text, covering 1241 to 1249, is in Paris's hand, though he is credited with the authorship of the whole text, which is an abridgement of the Chronica with additions from the annals of Reading and of Southwark. Additional interpolations to the text make it clear the volume was created for Westminster Abbey. It was apparently started there, copying another MS of Paris's text that went up to 1240. Later it was sent back to the author for him to update; Vaughan argues this was in 1251-2. The illustrations are similar to Paris's style but not by him. Later additions took the chronicle up to 1327.[6]

- Historia Anglorum. British Library, Royal MS 14 C VII, fols. 8v–156v.[7] 358 x 250 mm, ff 232 in all. A history of England, begun in 1250 and perhaps completed around 1255, covering the years 1070–1253. The text is an abridgement of the Chronica, also drawing on Wendover's Flores Historiarum and Paris's earlier edited version of the Chronica. Bound with it is the final part of Paris's Chronica Majora, covering the years 1254–1259 (folios 157–218), and prefatory material including an itinerary from London to Jerusalem and tinted drawings of the kings of England. All is in Paris's own hand, apart from folios 210–218 and 154v-156v, which are in a hand of the scribe who has added a note of Matthew Paris's death (f. 218v). The Chronica concludes with a portrait of Paris on his death-bed, presumably not by him.[8] By the 15th century this volume belonged to Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, son of Henry IV, who inscribed it "Ceste livre est a moy Homffrey Duc de Gloucestre". Later it was held by the bishop of Lincoln, who wrote a note that if the monks of St Albans could prove the book was a loan, they should have it back. Otherwise it was bequeathed to New College, Oxford. The fact that the book was acquired by a 16th-century Earl of Arundel suggests that Duke Humphrey's inscription was not entirely accurate, as New College would probably not have disposed of it.[9]

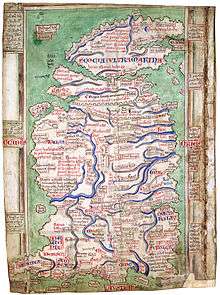

- Abbreviatio chronicorum (or Historia minor), British Library Cotton MS Claudius D VI, fols. 5–100.[10] Another shortened history, mainly covering 1067 to 1253. Probably begun circa 1255, it remained unfinished at Paris's death. Illustrated with thirty-three seated figures of English kings illustrating a genealogy. It also contains the most developed of Paris's four maps of Great Britain.

- Chronica excerpta a magnis cronicis. British Library Cotton MS Vitellius A XX, folios 77r–108v.[11] Covers from 1066 to 1246. Written at some point between 1246 and 1259. Not definitely by Paris, but evidently written under his supervision, with some of the text in his own hand.

- Book of Additions (Liber additamentorum) British Library Cotton MS Nero D I, ff202 in all, contains maps, Vitae duorum Offarum (illustrated), Gesta abbatum, the lives of the first 23 abbots of St Albans with a miniature portrait of each, coats of arms, as well as copies of original documents. A version of his well-known drawing of an elephant is in this volume, as is a large drawing of Christ, not by Paris.[12][13]

- Life of St Alban etc., dating controversial (1230–1250), Trinity College, Dublin Library, Ms 177 (former Ms E.I.40) 77 ff with 54 miniatures, mostly half-page. 240 x 165 mm. Also contains a Life of St Amphibalus, and various other works relating to the history of St Albans Abbey, both also illustrated. The Life of St Alban is in French verse, adapted from a Latin Life of St Alban by William of St Albans, ca. 1178. The manuscript also contains notes in Paris's hand (see above) showing that his manuscripts were lent to various aristocratic ladies for periods, and that he probably acted as an intermediary between commissioners of manuscripts and the (probably) lay artists who produced them, advising on the calendars and iconography.

- Life of King Edward the Confessor 1230s or 40s, Cambridge University Library MS. Ee.3.59.[14] This is the only surviving copy of this work, but is believed to be a slightly later copy made in London, probably by court artists, of Paris's text and framed illustrations. Based on the Latin Life of Edward the Confessor by Aelred of Rievaulx, c. 1162.

- Life of St Thomas of Canterbury, British Library Loan MS 88 – Four leaves (the "Becket Leaves") survive from a French-verse history of the life of Thomas Becket with large illuminations. Based on the Latin Quadrilogus compiled by Elias of Evesham at Crowland Abbey in 1198. The illuminations are attributed to Paris by Janet Backhouse, but not by Nigel Morgan. Vaughan had previously noted that the leaves from the Life of St Thomas and the Life of King Edward are of different sizes, and written by different scribes, neither of them Paris himself, so they are not likely to be part of the manuscript that Paris wrote of having lent to the Countess of Arundel; but that, "to judge from the script and the style of illumination" they are "very close copies of Matthew [Paris]'s original".[15]

- Life of St Edmund, a French-verse history of the life of Edmund Rich, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1233 to 1240. Based on Paris's own Latin prose life of Rich, composed in the late 1240s, which drew on a collection of materials made at Pontigny, statements from Robert Bacon and Richard Wych, Bishop of Chichester, and other materials including from Paris's own histories. A 14th-century copy of the prose life has survived in British Library Cotton MS Julius D VI, folios 123–156v.[16] One copy of the verse life that was in Cotton MS Vitellius D VIII was destroyed in the fire of 1731; but another copy was discovered in the early 1900s at Welbeck Abbey and is now in the British Library.[17]

- Liber Experimentarius of Bernardus Silvestris, and other fortune-telling tracts. Bodleian Library, Oxford, Ms. Ashmole 304, 176 x 128 mm, ff72. Many illustrations: author portraits (many of ancient Greeks – Socrates, Plato, Euclid, Pythagoras), birds, tables and diagrams of geomantic significance. Several later copies of the text and illustrations survive. Provenance before 1602 unknown.

- Miscellaneous writings by John of Wallingford (the Younger), British Library, MS Cotton Julius D VII,[18] 188 x 130mm, ff 134. 1247–58. Mostly scribed by John of Wallingford, another monk of St Albans, who also probably did some drawings. A portrait of John,[19] a map of the British Isles, and a Christ in Majesty are all accepted as by Paris. The main text is a chronicle, highly derivative of Paris's. This was John's property, left to his final monastery at Wymondham.

Also, fragments of a Latin biography of Stephen Langton. Various other works, especially maps.

A panel painting on oak of St Peter, the only surviving part of a tabernacle shrine (1850 x 750 mm), in the Museum of Oslo University has been attributed to Paris, presumably dating from his visit in 1248. Local paintings are usually on pine, so he may have brought this with him, or sent it later.[20]

Paris as an artist

Recent scholarship, notably that of Nigel Morgan, suggests that Paris's influence on other artists of the period has been exaggerated. This is likely because so much more is known about him than other English illuminators of the period, who are mostly anonymous. Most manuscripts seem to have been produced by lay artists in this period. William de Brailes is shown with a clerical tonsure, but he was married, which suggests he had minor orders only. The manuscripts produced by Paris show few signs of collaboration, but art historians detect a School of St Albans' surviving after Paris's death, influenced by him.

In some manuscripts, a framed miniature occupies the upper half of the page, and in others they are "marginal" – unframed and occupying the bottom quarter (approximately) of the page. Tinted drawings were an established style well before Paris, and became especially popular in the first half of the 13th century. They were certainly much cheaper and quicker than fully painted illuminations.

Paris's style suggests that it was formed by works from around 1200. He was somewhat old-fashioned in retaining a roundness in his figures, rather than adopting the thin angularity of most of his artist contemporaries, especially those in London. His compositions are very inventive; his position as a well-connected monk may have given him more confidence in creating new compositions, whereas a lay artist would prefer to stick to traditional formulae. It may also reflect the lack of full training in the art of the period. His colouring emphasises green and blue, and together with his characteristic layout of a picture in the top half of a page, is relatively distinctive. What are probably his final sketches are found in Vitae duorum Offarum in BL MS Cotton Nero D I.

Paris as an historian

From 1235, the point at which Wendover dropped his pen, Paris continued the history on the plan which his predecessors had followed. He derived much of his information from the letters of important people, which he sometimes inserts, but much more from conversation with the eyewitnesses of events. Among his informants were Richard, Earl of Cornwall and King Henry III, with whom he appears to have been on intimate terms.

The king knew that Paris was writing a history, and wanted it to be as exact as possible. In 1257, in the course of a week's visit to St Albans, Henry kept the chronicler beside him night and day, "and guided my pen," says Paris, "with much goodwill and diligence." It is curious that the Chronica majora gives so unfavourable an account of the king's policy. Henry Richards Luard supposes that Paris never intended his work to be read in its present form. Many passages of the autograph have written next to them, the note offendiculum, which shows that the writer understood the danger which he ran. On the other hand, unexpurgated copies were made in Paris's lifetime. Although the offending passages are duly omitted or softened in his abridgment of his longer work, the Historia Anglorum (written about 1253), Paris's real feelings must have been an open secret. There is no ground for the old theory that he was an official historiographer.

Matthew Paris lived at a time when English politics were extremely involved. His talent is for narrative and description. Though he took a keen interest in the personal side of politics, his portraits of his contemporaries throw more light on his own prejudices than on their aims and ideas. Like most "historians" of the period, he never pauses to weigh the evidence or to take a comprehensive view of the situation. He admires strength of character, even when it goes along with a policy of which he disapproves. Thus he praises Robert Grosseteste, while denouncing Grosseteste's scheme of monastic reform. Paris was a vehement supporter of the monastic orders against their rivals, the secular clergy and the mendicant friars. He was strongly opposed to the court and the foreign favourites. He thought the king inadequate as a statesman, although had some feeling for the man.

He attacked the court of Rome with surprising frankness, and also displayed considerable nationalism. His faults are often due to carelessness and narrow views, but he sometimes invents rhetorical speeches which are misleading as an account of the speaker's sentiments. In other cases he tampers with the documents which he inserts (as, for instance, with the text of Magna Carta). His chronology is, for a contemporary, inexact; and he occasionally inserts duplicate versions of the same incident in different places. Hence he must be rigorously checked when other authorities exist and used with caution where he is our sole informant. Nonetheless, he gives a more vivid impression of his age than any other English chronicler.

Naturalists have praised his descriptions of wildlife, brief though they are: in particular his valuable description of the first irruption into England in 1254 of the common crossbill.[21]

Studies of Matthew Paris

The relation of Matthew Paris's work to those of John de Celia (John of Wallingford) and Roger of Wendover may be studied in Henry Richards Luard's edition of the Chronica majora (7 vols., Rolls series, 1872–1881), which contains valuable prefaces. The Historia Anglorum sive historia minor (1067–1253) has been edited by Frederic Madden (3 vols., Rolls series, 1866–1869).

Matthew Paris is sometimes confused with "Matthew of Westminster", the reputed author of the Flores historiarum edited by Luard (3 vols., Rolls series, 1890). This work, compiled by various hands, is an edition of Matthew Paris, with continuations extending to 1326.

He wrote a life of St Edmund of Canterbury, which has been edited and translated by C.H. Lawrence (Oxford, 1996). He also wrote the Anglo-Norman La Estoire de Seint Aedward le Rei (the History of Saint Edward the King), which survives in a beautifully illuminated manuscript version, Cambridge, Cambridge University Library MS. Ee.3.59.[22] The text is edited in K.Y. Wallace, La Estoire de Seint Aedward le Rei, Anglo-Norman Text Society 41 (1983).

Paris House at St Albans High School for Girls is named after him.

Sources

(On manuscripts, and artistic style) Nigel Morgan, A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles, Volume 4: Early Gothic Manuscripts, Part 1 1190–1250, Harvey Miller Ltd, London, 1982, ISBN 0-19-921026-8

Notes

- ↑ John Allen Giles (translator), Matthew Paris's English history, from 1235 to 1273, Publ. 1852. (page v)

- ↑ Peter Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 58

- ↑ Matthew Paris, 'Matthew Paris on Staufer Italy'. In Jessalyn Bird, Edward Peters, and James M. Powell, Crusade and Christendom: Annotated Documents in Translation from Innocent III to the Fall of Acre, 1187-1291, p.405

- ↑ Edmund Carter (1819). The history of the county of Cambridge.

- ↑ British Library Archives and Manuscripts catalogue: Cotton MS Nero D V.

- ↑ Nigel Morgan in: Jonathan Alexander & Paul Binski (eds), Age of Chivalry, Art in Plantagenet England, 1200–1400, Royal Academy/Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London 1987, Cat 437

- ↑ British Library Digitised Manuscript information: Royal MS 14 C VII

- ↑ http://ibs001.colo.firstnet.net.uk/britishlibrary/controller/subjectidsearch?id=11624&&idx=1&startid=12427[]

- ↑ Showcases :: Matthew Paris' map of Great Britain

- ↑ British Library Archives and Manuscripts catalogue: Cotton MS Claudius D VI, fols. 5–100

- ↑ British Library Archives and Manuscripts catalogue: Cotton MS Vitellius A XX, ff 67–242.

- ↑ Itinerary From London To Chambery, In Matthew Paris's 'Book Of Additions'

- ↑ Matthew Paris’ “Lives of the Offas”, Christ of Revelations

- ↑ Paris, Matthew. "Life of St Edward the Confessor". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ Vaughn (1958), Matthew Paris, p. 171

- ↑ British Library Archives and Manuscripts catalogue: Cotton MS Julius D VI, ff 123r–156v.

- ↑ British Library Archives and Manuscripts catalogue: Add MS 70513, ff 85v-100.

- ↑ British Library Archives and Manuscripts catalogue: Cotton MS Julius D VII, ff 34r–115r.

- ↑ http://www.imagesonline.bl.uk/britishlibrary/controller/subjectidsearch?id=8541&&idx=1&startid=11208[]

- ↑ Nigel Morgan in: Jonathan Alexander & Paul Binski (eds), Age of Chivalry, Art in Plantagenet England, 1200–1400, Royal Academy/Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London 1987, Cat 311

- ↑ Perry, Richard Wildlife in Britain and Ireland Croom Helm Ltd London 1978 p.134

- ↑ Paris, Matthew. "Life of St Edward the Confessor". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bibliography

- Weiler, B., "Matthew Paris on the Writing of History," Journal of Medieval History, 35,3 (2009), 254–278.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Matthew Paris. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Matthew Paris |

- Images

- Stanford Digitized texts – Works by and about Paris, including Vaughan etc, in huge pdf files

- JSTOR review of Vaughan book

- Matthew Paris's Jerusalem pilgrim's travel guide: information, zoomable image British Library website

- Art Bulletin article on his maps;Imagined Pilgrimage in the Itinerary Maps of Matthew Paris. 12/1/1999 by Connolly, Daniel K

- Latin Chroniclers from the Eleventh to the Thirteenth Centuries:Matthew Paris from The Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Volume I, 1907–21.

- Life of St Edward the Confessor, Cambridge Digital Library

|