Mathematics of cyclic redundancy checks

The cyclic redundancy check (CRC) is based on division in the ring of polynomials over the finite field GF(2) (the integers modulo 2), that is, the set of polynomials where each coefficient is either zero or one, and arithmetic operations wrap around.

Any string of bits can be interpreted as the coefficients of a message polynomial of this sort, and to find the CRC, we multiply the message polynomial by  and then find the remainder when dividing by the degree-

and then find the remainder when dividing by the degree- generator polynomial. The coefficients of the remainder polynomial are the bits of the CRC.

generator polynomial. The coefficients of the remainder polynomial are the bits of the CRC.

Math

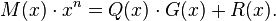

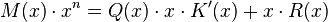

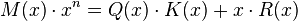

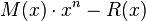

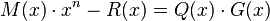

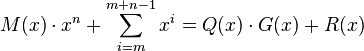

In general, computation of CRC corresponds to Euclidean division of polynomials over GF(2):

Here  is the original message polynomial and

is the original message polynomial and  is the degree-

is the degree- generator polynomial. The bits of

generator polynomial. The bits of  are the original message with

are the original message with  zeroes added at the end. The CRC 'checksum' is formed by the coefficients of the remainder polynomial

zeroes added at the end. The CRC 'checksum' is formed by the coefficients of the remainder polynomial  whose degree is strictly less than

whose degree is strictly less than  . The quotient polynomial

. The quotient polynomial  is of no interest. Using modulo operation, it can be stated that

is of no interest. Using modulo operation, it can be stated that

In communication, the sender attaches the  bits of R after the original message bits of M, which could be shown to be equivalent to sending out

bits of R after the original message bits of M, which could be shown to be equivalent to sending out  (the codeword.) The receiver, knowing

(the codeword.) The receiver, knowing  and therefore

and therefore  , separates M from R and repeats the calculation, verifying that the received and computed R are equal. If they are, then the receiver assumes the received message bits are correct.

, separates M from R and repeats the calculation, verifying that the received and computed R are equal. If they are, then the receiver assumes the received message bits are correct.

In practice CRC calculations most closely resemble long division in binary, except that the subtractions involved do not borrow from more significant digits, and thus become exclusive or operations.

A CRC is a checksum in a strict mathematical sense, as it can be expressed as the weighted modulo-2 sum of per-bit syndromes, but that word is generally reserved more specifically for sums computed using larger moduli, such as 10, 256, or 65535.

CRCs can also be used as part of error-correcting codes, which allow not only the detection of transmission errors, but the reconstruction of the correct message. These codes are based on closely related mathematical principles.

Polynomial arithmetic modulo 2

Since the coefficients are constrained to a single bit, any math operation on CRC polynomials must map the coefficients of the result to either zero or one. For example in addition:

Note that  becomes zero in the above equation because addition of coefficients is performed modulo 2:

becomes zero in the above equation because addition of coefficients is performed modulo 2:

Multiplication is similar:

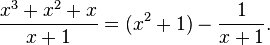

We can also divide polynomials mod 2 and find the quotient and remainder. For example, suppose we're dividing  by

by  . We would find that

. We would find that

In other words,

The division yields a quotient of x2 + 1 with a remainder of −1, which, since it is odd, has a last bit of 1.

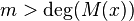

In the above equations,  represents the original message bits

represents the original message bits 111,  is the generator polynomial, and the remainder

is the generator polynomial, and the remainder  (equivalently,

(equivalently,  ) is the CRC. The degree of the generator polynomial is 1, so we first multiplied the message by

) is the CRC. The degree of the generator polynomial is 1, so we first multiplied the message by  to get

to get  .

.

Variations

There are several standard variations on CRCs, any or all of which may be used with any CRC polynomial. Implementation variations such as endianness and CRC presentation only affect the mapping of bit strings to the coefficients of  and

and  , and do not impact the properties of the algorithm.

, and do not impact the properties of the algorithm.

- To check the CRC, instead of calculating the CRC on the message and comparing it to the CRC, a CRC calculation may be run on the entire codeword. If the result is zero, the check passes. This works because the codeword is

, which is always divisible by

, which is always divisible by  .

.

- This simplifies many implementations by avoiding the need to treat the last few bytes of the message specially when checking CRCs.

- The shift register may be initialized with ones instead of zeroes. This is equivalent to inverting the first

bits of the message feeding them into the algorithm. The CRC equation becomes

bits of the message feeding them into the algorithm. The CRC equation becomes  , where

, where  is the length of the message in bits. The change this imposes on

is the length of the message in bits. The change this imposes on  is a function of the generating polynomial and the message length,

is a function of the generating polynomial and the message length,  .

.

- The reason this method is used is because an unmodified CRC does not distinguish between two messages which differ only in the number of leading zeroes, because leading zeroes do not affect the value of

. When this inversion is done, the CRC does distinguish between such messages.

. When this inversion is done, the CRC does distinguish between such messages.

- The CRC may be inverted before being appended to the message stream. While an unmodified CRC distinguishes between messages

with different numbers of trailing zeroes, it does not detect trailing zeroes appended after the CRC remainder itself. This is because all valid codewords are multiples of

with different numbers of trailing zeroes, it does not detect trailing zeroes appended after the CRC remainder itself. This is because all valid codewords are multiples of  , so

, so  times that codeword is also a multiple. (In fact, this is precisely why the first variant described above works.)

times that codeword is also a multiple. (In fact, this is precisely why the first variant described above works.)

In practice, the last two variations are invariably used together. They change the transmitted CRC, so must be implemented at both the transmitter and the receiver. While presetting the shift register to ones is straightforward to do at both ends, inverting affects receivers implementing the first variation, because the CRC of a full codeword that already includes a CRC is no longer zero. Instead, it is a fixed non-zero pattern, the CRC of the inversion pattern of  ones.

ones.

The CRC thus may be checked either by the obvious method of computing the CRC on the message, inverting it, and comparing with the CRC in the message stream, or by calculating the CRC on the entire codeword and comparing it with an expected fixed value  , called the check polynomial, residue or magic number. This may be computed as

, called the check polynomial, residue or magic number. This may be computed as  , or equivalently by computing the unmodified CRC of a message consisting of

, or equivalently by computing the unmodified CRC of a message consisting of  ones,

ones,  .

.

These inversions are extremely common but not universally performed, even in the case of the CRC-32 or CRC-16-CCITT polynomials.

Reversed representations and reciprocal polynomials

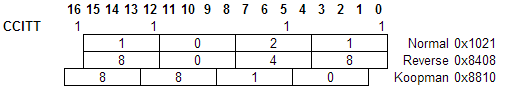

Polynomial representations

All the well-known CRC generator polynomials of degree  have two common hexadecimal representations. In both cases, the coefficient of

have two common hexadecimal representations. In both cases, the coefficient of  is omitted and understood to be 1.

is omitted and understood to be 1.

- The msbit-first representation is a hexadecimal number with

bits, the least significant bit of which is always 1. The most significant bit represents the coefficient of

bits, the least significant bit of which is always 1. The most significant bit represents the coefficient of  and the least significant bit represents the coefficient of

and the least significant bit represents the coefficient of  .

. - The lsbit-first representation is a hexadecimal number with

bits, the most significant bit of which is always 1. The most significant bit represents the coefficient of

bits, the most significant bit of which is always 1. The most significant bit represents the coefficient of  and the least significant bit represents the coefficient of

and the least significant bit represents the coefficient of  .

.

The msbit-first form is often referred to in the literature as the normal representation, while the lsbit-first is called the reversed representation. It is essential to use the correct form when implementing a CRC. If the coefficient of  happens to be zero, the forms can be distinguished at a glance by seeing which end has the bit set.

happens to be zero, the forms can be distinguished at a glance by seeing which end has the bit set.

To further confuse the matter, the paper by P. Koopman and T. Chakravarty [1][2] converts CRC generator polynomials to hexadecimal numbers in yet another way: msbit-first, but including the  coefficient and omitting the

coefficient and omitting the  coefficient. This "Koopman" representation has the advantage that the degree can be determined from the hexadecimal form and the coefficients are easy to read off in left-to-right order. However, it is not used anywhere else and is not recommended due to the risk of confusion.

coefficient. This "Koopman" representation has the advantage that the degree can be determined from the hexadecimal form and the coefficients are easy to read off in left-to-right order. However, it is not used anywhere else and is not recommended due to the risk of confusion.

Reciprocal polynomials

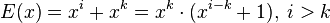

A reciprocal polynomial is created by assigning the  through

through  coefficients of one polynomial to the

coefficients of one polynomial to the  through

through  coefficients of a new polynomial. That is, the reciprocal of the degree

coefficients of a new polynomial. That is, the reciprocal of the degree  polynomial

polynomial  is

is  .

.

The most interesting property of reciprocal polynomials, when used in CRCs, is that they have exactly the same error-detecting strength as the polynomials they are reciprocals of. The reciprocal of a polynomial generates the same codewords, only bit reversed — that is, if all but the first  bits of a codeword under the original polynomial are taken, reversed and used as a new message, the CRC of that message under the reciprocal polynomial equals the reverse of the first

bits of a codeword under the original polynomial are taken, reversed and used as a new message, the CRC of that message under the reciprocal polynomial equals the reverse of the first  bits of the original codeword. But the reciprocal polynomial is not the same as the original polynomial, and the CRCs generated using it are not the same (even modulo bit reversal) as those generated by the original polynomial.

bits of the original codeword. But the reciprocal polynomial is not the same as the original polynomial, and the CRCs generated using it are not the same (even modulo bit reversal) as those generated by the original polynomial.

Error detection strength

The error-detection ability of a CRC depends on the degree of its key polynomial and on the specific key polynomial used. The "error polynomial"  is the symmetric difference of the received message codeword and the correct message codeword. An error will go undetected by a CRC algorithm if and only if the error polynomial is divisible by the CRC polynomial.

is the symmetric difference of the received message codeword and the correct message codeword. An error will go undetected by a CRC algorithm if and only if the error polynomial is divisible by the CRC polynomial.

- Because a CRC is based on division, no polynomial can detect errors consisting of a string of zeroes prepended to the data, or of missing leading zeroes. However, see Variations.

- All single bit errors will be detected by any polynomial with at least two terms with non-zero coefficients. The error polynomial is

, and

, and  is divisible only by polynomials

is divisible only by polynomials  where

where  .

. - All two bit errors separated by a distance less than the order of the primitive polynomial which is a factor of the generator polynomial will be detected. The error polynomial in the two bit case is

. As noted above, the

. As noted above, the  term will not be divisible by the CRC polynomial, which leaves the

term will not be divisible by the CRC polynomial, which leaves the  term. By definition, the smallest value of

term. By definition, the smallest value of  such that a polynomial divides

such that a polynomial divides  is the polynomial's order or exponent. The polynomials with the largest order are called primitive polynomials, and for polynomials of degree

is the polynomial's order or exponent. The polynomials with the largest order are called primitive polynomials, and for polynomials of degree  with binary coefficients, have order

with binary coefficients, have order  .

. - All errors in an odd number of bits will be detected by a polynomial which is a multiple of

. This is equivalent to the polynomial having an even number of terms with non-zero coefficients. This capacity assumes that the generator polynomial is the product of

. This is equivalent to the polynomial having an even number of terms with non-zero coefficients. This capacity assumes that the generator polynomial is the product of  and a primitive polynomial of degree

and a primitive polynomial of degree  since all primitive polynomials except

since all primitive polynomials except  have an odd number of non-zero coefficients.

have an odd number of non-zero coefficients. - All burst errors of length

will be detected by any polynomial of degree

will be detected by any polynomial of degree  or greater which has a non-zero

or greater which has a non-zero  term.

term.

(As an aside, there is never reason to use a polynomial with a zero  term. Recall that a CRC is the remainder of the message polynomial times x^n divided by the CRC polynomial. A polynomial with a zero

term. Recall that a CRC is the remainder of the message polynomial times x^n divided by the CRC polynomial. A polynomial with a zero  term always has

term always has  as a factor. So if

as a factor. So if  is the original CRC polynomial and

is the original CRC polynomial and  , then

, then

That is, the CRC of any message with the  polynomial is the same as that of the same message with the

polynomial is the same as that of the same message with the  polynomial with a zero appended. It is just a waste of a bit.)

polynomial with a zero appended. It is just a waste of a bit.)

The combination of these factors means that good CRC polynomials are often primitive polynomials (which have the best 2-bit error detection) or primitive polynomials of degree  , multiplied by

, multiplied by  (which detects all odd numbers of bit errors, and has half the two-bit error detection ability of a primitive polynomial of degree

(which detects all odd numbers of bit errors, and has half the two-bit error detection ability of a primitive polynomial of degree  ).[1]

).[1]

Bitfilters

Analysis Technique using bitfilters[1] allows one to very efficiently determine the properties of a given generator polynomial. The results are the following:

- All burst errors (but one) with length no longer than the generator polynomial can be detected by any generator polynomial

. This includes 1-bit errors (burst of length 1). The maximum length is

. This includes 1-bit errors (burst of length 1). The maximum length is  , when

, when  is the degree of the generator polynomial (which itself has a length of

is the degree of the generator polynomial (which itself has a length of  ). The exception to this result is a bit pattern the same as that of the generator polynomial.

). The exception to this result is a bit pattern the same as that of the generator polynomial. - All uneven bit errors are detected by generator polynomials with even number of terms.

- 2-bit errors in a (multiple) distance of the longest bitfilter of even parity to a generator polynomial are not detected; all others are detected. For degrees up to 32 there is an optimal generator polynomial with that degree and even number of terms; in this case the period mentioned above is

. For

. For  this means that blocks of 32767 bits length do not contain undiscovered 2-bit errors. For uneven number of terms in the generator polynomial there can be a period of

this means that blocks of 32767 bits length do not contain undiscovered 2-bit errors. For uneven number of terms in the generator polynomial there can be a period of  ; however, these generator polynomials (with odd number of terms) do not discover all odd number of errors, so they should be avoided. A list of the corresponding generators with even number of terms can be found in the link mentioned at the beginning of this section.

; however, these generator polynomials (with odd number of terms) do not discover all odd number of errors, so they should be avoided. A list of the corresponding generators with even number of terms can be found in the link mentioned at the beginning of this section. - All single bit errors within the bitfilter period mentioned above (for even terms in the generator polynomial) can be identified uniquely by their residual. So CRC method can be used to correct single-bit errors as well (within those limits, e.g. 32767 bits with optimal generator polynomials of degree 16). Since all odd errors leave an odd residual, all even an even residual, 1-bit errors and 2-bit errors can be distinguished. However, like other SECDED techniques, CRCs cannot always distinguish between 1-bit errors and 3-bit errors. When 3 or more bit errors occur in a block, CRC bit error correction will be erroneous itself and produce more errors.

See also

- Error correcting code

- List of checksum algorithms

- Parity (telecommunication)

- Polynomial representations of cyclic redundancy checks

References

- 1 2 3 Koopman, Philip (July 2002). "32-Bit Cyclic Redundancy Codes for Internet Applications" (PDF). The International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks: 459–468. doi:10.1109/DSN.2002.1028931. Retrieved 14 January 2011. - verification of Castagnoli's results by exhaustive search and some new good polynomials

- ↑ Koopman, Philip; Chakravarty, Tridib (June 2004). "Cyclic Redundancy Code (CRC) Polynomial Selection For Embedded Networks" (PDF). The International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks: 145–154. doi:10.1109/DSN.2004.1311885. Retrieved 14 January 2011. – analysis of short CRC polynomials for embedded applications