On shell and off shell

In physics, particularly in quantum field theory, configurations of a physical system that satisfy classical equations of motion are called on shell, and those that do not are called off shell.

In quantum field theory, virtual particles are termed off shell (mass-shell in this case) because they don't satisfy the Einstein energy-momentum relationship; real exchange particles do satisfy this relation and are termed on shell (mass-shell).[1] In classical mechanics for instance, in the action formulation, extremal solutions to the variational principle are on shell and the Euler–Lagrange equations give the on shell equations. Noether's theorem is also another on shell theorem.

Mass shell

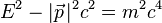

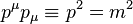

The term is a synonym for mass hyperboloid, meaning the hyperboloid in energy–momentum space describing the solutions to the equation:

which gives the energy E in terms of the momentum  and the rest mass m of a particle in classical special relativity. The equation for the mass shell is also often written in terms of the four-momentum; in Einstein notation with metric signature (+,–,–,–) and units where the speed of light c = 1, as

and the rest mass m of a particle in classical special relativity. The equation for the mass shell is also often written in terms of the four-momentum; in Einstein notation with metric signature (+,–,–,–) and units where the speed of light c = 1, as  . In the literature, one may also encounter

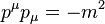

. In the literature, one may also encounter  if the metric signature used is (–,+,+,+).

if the metric signature used is (–,+,+,+).

Virtual particles corresponding to internal propagators in a Feynman diagram are in general allowed to be off shell, but the amplitude for the process will diminish depending on how far off shell they are. This is because the  -dependence of the propagator is determined by the four-momenta of the incoming and outgoing particles. The propagator typically has singularities on the mass shell.[2]

-dependence of the propagator is determined by the four-momenta of the incoming and outgoing particles. The propagator typically has singularities on the mass shell.[2]

When speaking of the propagator, negative values for E that satisfy the equation are thought of as being on shell, though the classical theory does not allow negative values for the energy of a particle. This is because the propagator incorporates into one expression the cases in which the particle carries energy in one direction, and in which its antiparticle carries energy in the other direction; negative and positive on-shell E then simply represent opposing flows of positive energy.

Scalar field

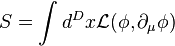

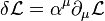

An example comes from considering a scalar field in D-dimensional Minkowski space. Consider a Lagrangian density given by  . The action

. The action

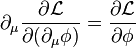

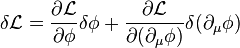

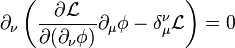

The Euler-Lagrange equation for this action can be found by varying the field and its derivative and setting the variation to zero, and is:

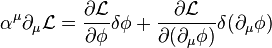

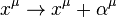

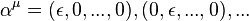

Now, consider an infinitesimal spacetime translation  . The Lagrangian density

. The Lagrangian density  is a scalar, and so will transform as

is a scalar, and so will transform as  . By Taylor-expanding the Lagrangian density, we can find another equivalent expression for

. By Taylor-expanding the Lagrangian density, we can find another equivalent expression for  :

:

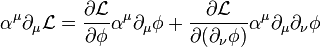

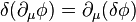

Substituting for  and noting that

and noting that  (since the variations are independent at each point in spacetime):

(since the variations are independent at each point in spacetime):

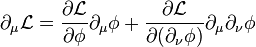

But the fields themselves are scalars, so they transform exactly like  :

:

Since this has to hold for independent translations  , we may "divide" by

, we may "divide" by  and write:

and write:

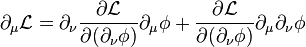

This is an example of equation that holds off shell, since it is true for any fields configuration regardless of whether it respects the equations of motion (in this case, the Euler-Lagrage equation given above). However, we can derive an on shell equation by simply substituting the Euler-Lagrange equation:

We can write this as:

And if we define the quantity in brackets as  , we have:

, we have:

This is an instance of Noether's theorem. Here, the conserved quantity is the stress–energy tensor, which is only conserved on shell, that is, if the equations of motion are satisfied.