Mazar (mausoleum)

A mazār (Arabic: مزار) is a mausoleum or shrine in some places of the world, typically that of a saint or notable religious leader. Medieval Arabic texts may also use the words mašhad, maqām or ḍarīḥ to denote the same concept.[1] Another synonymous term mostly used in Palestine and in older Western scholarly literature is wali' or weli.

Etymology

- Mazār, plural mazārāt, is related to the word ziyāra (زياره), meaning 'pious visitation'. It refers to a place and time of visiting.[2] Arabic in origin, the word has been borrowed by Persian and Urdu.

Specific types of shrines

- Mashhad (مشهد), plural mashāhid, usually refers to a structure holding the tomb of a holy figure, or a place where a religious visitation occurred. Related words are shāhid (‘witness’) and shahīd (‘martyr’).[1][lower-alpha 1] A mashhad often had a dome over the place of the burial within the building. Some had a minaret.[4]

- Maqām, plural maqāmāt, literally "a place of the feet", referring to where one stays or resides, is often used for Ahl al-Bayt shrines.[5] According to Ibn Taymiyya, the maqāmāt are the places where the revered person lived, died or worshiped, and the mashāhidd are buildings over the maqāmāt or over relics of the person.[2]

Regional terms for equivalent structures

- Mazār is the Arabic word borrowed by Persian and Urdu. It is thus largely used in Iran and other countries influenced by Persian culture, in Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

- Weli, plural awliya: in Palestine, weli is the common term both for a saint and his sanctuary. A prophet's weli is called a hadrah, a common saint's is a maqam and a famous saint has a mashhad.[6] 19th- to early 20th-century Western literature has adopted the word wali, sometimes written "weli", "welli" etc., with the meaning of a tomb or mausoleum of a holy man.[7]

- Qubba, plural qubbat, lit. "dome": in Sudan, the tomb of a holy man. Sudanese folk Islam holds that the holy man is sharing his baraka or blessings also after death through his grave, which is the repository for his baraka and thus becomes a place of ziyara ziyarat or visitation. A holy man worthy of such a shrine is called in Sudan a wali, faki, or shaykh.[8]

- In northwest China, a gongbei, meaning "dome", is a shrine complex centered on a grave of a Sufi master of the Hui people.

- In Iran, a dargah is a Sufi Islamic shrine built over the grave of a revered religious figure.

- In South Africa (especially the Western Cape), a kramat is the grave of a spiritual leader or auliya, sometimes inside a rectangular building that functions also as a shrine for the deceased (often a Cape Malay).

- In Indonesia, the terms makam and kuburan refer to graves of early missionaries, notably the Wali Songo saints of Java.

Related terms

- Masjid, plural masājid, means a place of prostration or prayer, and is often used by Shi'a for shrines to which mosques have been attached.[2]

- Darīh, plural adriha, is a trench in the middle of the grave, or the grave itself.[5]

Origins

Practices vary considerably in different countries. Syncretism is not unusual, where pre-Islamic practices and beliefs persist among Muslim communities.[9] Despite Muhammad's wishes and Allah's command, a cult of saints developed within some Muslim communities at an early date, following deeply ingrained pre-Islamic practices in the Middle East. Mashhads, or sanctuaries, were established by certain people for figures mentioned from the Quran such as Muhammad, Jesus, the prophets and other main figures of the Jewish and Christian Bible, great rulers, military leaders and clerics.[10]

Sufi mystics developed the concept of Wahdat al-Wujud, in which God and the universe are considered coterminous. This doctrine, very similar to the Vedantic doctrine of non-duality, may be used to justify idolatry and tomb worship. For this reason, some Muslims consider that Sufism,is not Islam.[11]

Opponents

The Salaf as Saaliheen consider that no person can mediate between man and God. Even the Prophet was a man not expected to be worshiped. They consider that Muslims who believe that saints and their shrines have holy properties are polytheists and heretics. In 1802, Salaf forces invaded Karbala where they partially destroyed the shrine of Imam Husayn.[12]Shi'a claim that In 1925 the commander and later king of Saudi Arabia, Abdulaziz Ibn Saud, destroyed the cemetery of Jannat al-Baghi in Medina, the burial place of four of the Shia imams and of the Prophet's daughter.[12] However, the cemetery is apparently still in existence and is used daily to bury the dead.

Design

There is no specific architectural type for mazārs, which vary greatly in size and elaboration. However, they all follow the conventional design of the turba, or tomb, and generally have a dome over a rectangular base.[10]

Notable examples

- In Iraq

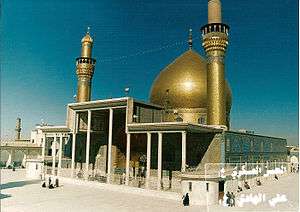

The Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala, Iraq draws Shia pilgrims from Iraq, Iran and elsewhere.

The Sardāb of Caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775–785) is preserved in Samarra, Iraq under a golden dome that was presented by Naser al-Din Shah Qajar and that was completed by Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar in 1905.[13] The tomb lies within the Al-Askari Mosque, one of the most important of Shia shrines. The mosque was badly damaged in a February 2006 bombing, presumably the work of Sunni militants.[14]

- In Iran

As of 2007, the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad, Iran attracted 12 million visitors annually, second only to Mecca as a destination for Muslim pilgrims. This shrine is known for its healing powers.

The shrine of Princess Shahrbanu, just south of Tehran, is open only to women. Shahrbanu was the daughter of Yazdegerd III, the last Sassanid ruler of Persia. She married Imam Hussein ibn Ali and was mother of the fourth Shia imam, Ali ibn al-Husayn, so has come to symbolize the early and close connection between Shiism and Iran. The shrine is popular with women seeking solace or assistance.[15]

- In Syria

The Sayyidah Zaynab Mosque, which holds the shrine of Zaynab bint Ali in Damascus, has been restored with the help of contributions from Shias from India, Pakistan, Iran and elsewhere.[16] The shrine is one of the most important Shia sites in Syria, and draws many pilgrims from Iraq, Lebanon and Iran. In September 2008 a car bomb was detonated outside the shrine, killing 17.[17]

In Aleppo, the Mashhad al-Husayn from the Ayyubid period is the most important of Syrian medieval buildings.[18] The shrine of al-Husayn was built on a place indicated to a shepherd by a holy man who appeared to him in a dream, and was built by members of the local Shia community.[19] The present building is a reconstruction: the original suffered severe damage in 1918 from a huge explosion, and for forty years lay in ruins.[18] The original restoration largely succeeded in restoring the mashhad to its former appearance. Later additions included covering the courtyard with a steel frame canopy and adding a brightly decorated "shrine", which have given the monument a very different character from the original.[19]

- In Egypt

In Egypt, many mashhads devoted to religious figures were built in Fatimid Cairo, mostly straightforward square structures with a dome. A few of the mausoleums at Aswan were more complex and included side rooms.[20] Most of the Fatimid mausoleums have either been destroyed or have been greatly altered through later renovations. The Mashad al-Juyushi, also called Mashad Badr al-Jamali, is an exception. This building has a prayer hall covered with cross-vaults, with a dome resting on squinches over the area in front of the mihrab. It has a courtyard with a tall square minaret. It is not clear whom the mashhad commemorates.[21]

Two other important mashads from the Fatimid era in Cairo are those of Sayyida Ruqayya and Yayha al-Shabib, in the Fustat cemetery. Sayyida Ruqayya, a descendant of Ali, never visited Egypt, but the mashhad was built to commemorate her. It is similar to al-Juyushi, but with a larger, fluted dome and with an elegantly decorated mihrab.[22]

- In Pakistan

Some shrines draw both Sunni and Shia pilgrims. One example is the shrine of Abdol-Ghazi Sahab in Karachi, said to be a relative of Ja'far al-Sadiq, the sixth imam. He had fled from the Abbasids in Baghdad to Sindh, where he was given refuge by a Hindu prince.[23] The Shias venerate him as a member of the family of imams, while the Sunni simply see him as a person of great sanctity.

Another example is the Lahore shrine of Bibi Pak Daman, thought to be the place of burial of one of Ali's daughters and four other women of the Prophet's family.[23] The famous Sufi saint of the Sunni branch of Islam, Sayyid Ali Hujwiri (died 1071), once meditated for forty days in this shrine.[24]

Other noted shrines

- In Uzbekistan

- Mausoleum of Sheihantaur in Tashkent, Uzbekistan

- In Kyrgyzstan

- Manas Ordo Mausoleum of Manas in Talas Province, Kyrgyzstan

- In Afghanistan

- Shrine of the Cloak in Kandahar, Afghanistan. It contains a cloak believed to have been worn by Muhammad.

- Shrine of Hazrat Ali in Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan. One of the reputed burial places of Ali.

- In China

- Afaq Khoja Mausoleum near Kashgar in Xinjiang, China, tomb of Muhammad Yūsuf and his son Afaq Khoja

- In Pakistan

- Shrine of Data Ganj Baksh near Bhati Gate, in Lahore's Walled City, Pakistan.

- Mazar-e-Quaid, tomb of the founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, in Karachi, Pakistan.

- Mazar of Sultan Bahu, the founder of Sarwari Qadri order in Garh Maharaja, in Lahore, Pakistan.

- In India

- Dargah Nizamuddin, founder of Chisti Nizami order, in Delhi, India.

- Laila Majnu Ki Mazar, near Anupgarh, Rajasthan, India. According to local legend Laila and Majnun died here.

- Mausoleum of Fakhruddin Shaheed in Galiakot, Rajasthan, India.

- In Bangladesh

- Shrine of Bayazid Bostami in Chittagong, Bangladesh

- Shrine of Hazrat Shah Jalal in Sylhet, Bangladesh.

- In Indonesia

- Imogiri in Java, mausoleum complex of the sultans of Mataram, Yogyakarta and Surakarta.

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ The city of Mashhad in Iran takes its name from the sense of mashhad meaning "place of martyrdom". It is the place where the eighth Imam Ali Al-Ridha was martyred.[3]

Citations

- 1 2 Sandouby 2008, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Sandouby 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Halm 2007, p. 26.

- ↑ Sandouby 2008, p. 17.

- 1 2 Sandouby 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ Moshe Sharon (1998). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae (CIAP), Volume Two: B-C. Brill Academic Publishing. p. 172. ISBN 9789004110830. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ Guérin, 1880, p. 488

- ↑ Robert S. Kramer, Richard A. Lobban Jr., Carolyn Fluehr-Lobban (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Sudan. Historical Dictionaries of Africa (4 ed.). Lanham, Maryland, USA: Scarecrow Press, an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-8108-6180-0. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

QUBBA. The Arabic name for the tomb of a holy man... A qubba is usually erected over the grave of a holy man identified variously as wali (saint), faki, or shaykh since, according to folk Islam, this is where his baraka [blessings] is believed to be strongest...

- ↑ Burman 2002, p. 9.

- 1 2 Houtsma 1993, p. 425.

- ↑ Burman 2002, p. 10.

- 1 2 Nasr 2007, p. 97.

- ↑ Houtsma 1993, p. 488.

- ↑ Rabasa, Chalk & Cragin 2006, p. 51.

- ↑ Nasr 2007, p. 63.

- ↑ Nasr 2007, p. 56.

- ↑ Syrian car bomb attack kills 17.

- 1 2 Tabbaa 1997, p. 110.

- 1 2 Tabbaa 1997, p. 111.

- ↑ Kuiper 2009, p. 164.

- ↑ Petersen 2002, p. 45.

- ↑ Petersen 2002, p. 45-46.

- 1 2 Nasr 2007, p. 58.

- ↑ Nasr 2007, p. 59.

Sources

- Burman, J. J. Roy (2002). Hindu-Muslim Syncretic Shrines and Communities. Mittal Publications. ISBN 978-81-7099-839-6. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Halm, Heinz (2007-07-01). The shiites: a short history. Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55876-436-1. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Houtsma, M. Th (1993). First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936. BRILL. p. 425. ISBN 978-90-04-09796-4. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Kuiper, Kathleen (2009-12-11). Islamic Art, Literature, and Culture. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-61530-097-6. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Nasr, Vali (2007-04-17). The Shia Revival: How Conflicts within Islam Will Shape the Future. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06640-1. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- Petersen, Andrew (2002-03-11). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-20387-3. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Rabasa, Angel; Chalk, Peter; Cragin, Kim; Sara A. Daly, Heather S. Gregg (2006). Beyond al-Qaeda: Part 2, The Outer Rings of the Terrorist Universe. Rand Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-4105-0. Retrieved 2013-03-12. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Sandouby, Aliaa Ezzeldin Ismail (2008). The Ahl Al-bayt in Cairo and Damascus: The Dynamics of Making Shrines for the Family of the Prophet. ProQuest. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-549-72466-7. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- "Syrian car bomb attack kills 17". BBC News. 27 September 2008. Retrieved 2013-03-13.

- Tabbaa, Yasser (1997). Constructions of Power and Piety in Medieval Aleppo. Penn State Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-271-04331-9. Retrieved 2013-03-12.