Martingale (probability theory)

In probability theory, a martingale is a model of a fair game where knowledge of past events never helps predict the mean of the future winnings. In particular, a martingale is a sequence of random variables (i.e., a stochastic process) for which, at a particular time in the realized sequence, the expectation of the next value in the sequence is equal to the present observed value even given knowledge of all prior observed values.

To contrast, in a process that is not a martingale, it may still be the case that the expected value of the process at one time is equal to the expected value of the process at the next time. However, knowledge of the prior outcomes (e.g., all prior cards drawn from a card deck) may be able to reduce the uncertainty of future outcomes. Thus, the expected value of the next outcome given knowledge of the present and all prior outcomes may be higher than the current outcome if a winning strategy is used. Martingales exclude the possibility of winning strategies based on game history, and thus they are a model of fair games.

History

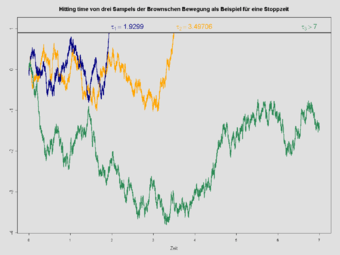

Originally, martingale referred to a class of betting strategies that was popular in 18th-century France.[1][2] The simplest of these strategies was designed for a game in which the gambler wins his stake if a coin comes up heads and loses it if the coin comes up tails. The strategy had the gambler double his bet after every loss so that the first win would recover all previous losses plus win a profit equal to the original stake. As the gambler's wealth and available time jointly approach infinity, his probability of eventually flipping heads approaches 1, which makes the martingale betting strategy seem like a sure thing. However, the exponential growth of the bets eventually bankrupts its users, assuming the obvious and realistic finite bankrolls (one of the reasons casinos, though normatively enjoying a mathematical edge in the games offered to their patrons, impose betting limits). Stopped Brownian motion, which is a martingale process, can be used to model the trajectory of such games.

The concept of martingale in probability theory was introduced by Paul Lévy in 1934, though he did not name them: the term "martingale" was introduced later by Ville (1939), who also extended the definition to continuous martingales. Much of the original development of the theory was done by Joseph Leo Doob among others. Part of the motivation for that work was to show the impossibility of successful betting strategies.

Definitions

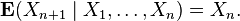

A basic definition of a discrete-time martingale is a discrete-time stochastic process (i.e., a sequence of random variables) X1, X2, X3, ... that satisfies for any time n,

That is, the conditional expected value of the next observation, given all the past observations, is equal to the last observation. Due to the linearity of expectation, this second requirement is equivalent to:

or

or

which states that the average "winnings" from observation  to observation

to observation  are 0.

are 0.

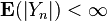

Martingale sequences with respect to another sequence

More generally, a sequence Y1, Y2, Y3 ... is said to be a martingale with respect to another sequence X1, X2, X3 ... if for all n

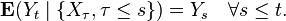

Similarly, a continuous-time martingale with respect to the stochastic process Xt is a stochastic process Yt such that for all t

This expresses the property that the conditional expectation of an observation at time t, given all the observations up to time  , is equal to the observation at time s (of course, provided that s ≤ t).

, is equal to the observation at time s (of course, provided that s ≤ t).

General definition

In full generality, a stochastic process  is a martingale with respect to a filtration

is a martingale with respect to a filtration  and probability measure P if

and probability measure P if

- Σ∗ is a filtration of the underlying probability space (Ω, Σ, P);

- Y is adapted to the filtration Σ∗, i.e., for each t in the index set T, the random variable Yt is a Σt-measurable function;

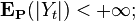

- for each t, Yt lies in the Lp space L1(Ω, Σt, P; S), i.e.

- for all s and t with s < t and all F ∈ Σs,

- where χF denotes the indicator function of the event F. In Grimmett and Stirzaker's Probability and Random Processes, this last condition is denoted as

- which is a general form of conditional expectation.[3]

It is important to note that the property of being a martingale involves both the filtration and the probability measure (with respect to which the expectations are taken). It is possible that Y could be a martingale with respect to one measure but not another one; the Girsanov theorem offers a way to find a measure with respect to which an Itō process is a martingale.

Examples of martingales

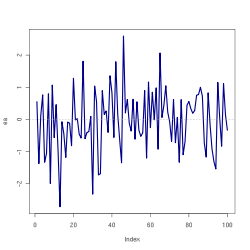

- An unbiased random walk (in any number of dimensions) is an example of a martingale.

- A gambler's fortune (capital) is a martingale if all the betting games which the gambler plays are fair.

- Polya's urn contains a number of different coloured marbles, and each iteration a marble is randomly selected out of the urn and replaced with several more of that same colour. For any given colour, the ratio of marbles inside the urn with that colour is a martingale. For example, if currently 95% of the marbles are red then—though the next iteration is much more likely add more red marbles—this bias is exactly balanced out by the fact that adding more red marbles alters the ratio much less significantly than adding the same number of non-red marbles would.

- Suppose Xn is a gambler's fortune after n tosses of a fair coin, where the gambler wins $1 if the coin comes up heads and loses $1 if the coin comes up tails. The gambler's conditional expected fortune after the next trial, given the history, is equal to his present fortune, so this sequence is a martingale.

- Let Yn = Xn2 − n where Xn is the gambler's fortune from the preceding example. Then the sequence { Yn : n = 1, 2, 3, ... } is a martingale. This can be used to show that the gambler's total gain or loss varies roughly between plus or minus the square root of the number of steps.

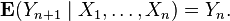

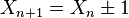

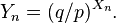

- (de Moivre's martingale) Now suppose an "unfair" or "biased" coin, with probability p of "heads" and probability q = 1 − p of "tails". Let

- with "+" in case of "heads" and "−" in case of "tails". Let

- Then { Yn : n = 1, 2, 3, ... } is a martingale with respect to { Xn : n = 1, 2, 3, ... }. To show this

-

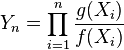

- (Likelihood-ratio testing in statistics) A population is thought to be distributed according to either a probability density f or another probability density g. A random sample is taken, the data being X1, ..., Xn. Let Yn be the "likelihood ratio"

- (which, in applications, would be used as a test statistic). If the population is actually distributed according to the density f rather than according to g, then { Yn : n = 1, 2, 3, ... } is a martingale with respect to { Xn : n = 1, 2, 3, ... }.

- Suppose each amoeba either splits into two amoebas, with probability p, or eventually dies, with probability 1 − p. Let Xn be the number of amoebas surviving in the nth generation (in particular Xn = 0 if the population has become extinct by that time). Let r be the probability of eventual extinction. (Finding r as function of p is an instructive exercise. Hint: The probability that the descendants of an amoeba eventually die out is equal to the probability that either of its immediate offspring dies out, given that the original amoeba has split.) Then

- is a martingale with respect to { Xn: n = 1, 2, 3, ... }.

- In an ecological community (a group of species that are in a particular trophic level, competing for similar resources in a local area), the number of individuals of any particular species of fixed size is a function of (discrete) time, and may be viewed as a sequence of random variables. This sequence is a martingale under the unified neutral theory of biodiversity and biogeography.

- If { Nt : t ≥ 0 } is a Poisson process with intensity λ, then the compensated Poisson process { Nt − λt : t ≥ 0 } is a continuous-time martingale with right-continuous/left-limit sample paths.

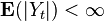

Submartingales, supermartingales, and relationship to harmonic functions

There are two popular generalizations of a martingale that also include cases when the current observation Xn is not necessarily equal to the future conditional expectation E[Xn+1|X1,...,Xn] but instead an upper or lower bound on the conditional expectation. These definitions reflect a relationship between martingale theory and potential theory, which is the study of harmonic functions. Just as a continuous-time martingale satisfies E[Xt|{Xτ : τ≤s}] − Xs = 0 ∀s ≤ t, a harmonic function f satisfies the partial differential equation Δf = 0 where Δ is the Laplacian operator. Given a Brownian motion process Wt and a harmonic function f, the resulting process f(Wt) is also a martingale.

- A discrete-time submartingale is a sequence

of integrable random variables satisfying

of integrable random variables satisfying

- Likewise, a continuous-time submartingale satisfies

- In potential theory, a subharmonic function f satisfies Δf ≥ 0. Any subharmonic function that is bounded above by a harmonic function for all points on the boundary of a ball are bounded above by the harmonic function for all points inside the ball. Similarly, if a submartingale and a martingale have equivalent expectations for a given time, the history of the submartingale tends to be bounded above by the history of the martingale. Roughly speaking, the prefix "sub-" is consistent because the current observation Xn is less than (or equal to) the conditional expectation E[Xn+1|X1,...,Xn]. Consequently, the current observation provides support from below the future conditional expectation, and the process tends to increase in future time.

- Analogously, a discrete-time supermartingale satisfies

- Likewise, a continuous-time supermartingale satisfies

- In potential theory, a superharmonic function f satisfies Δf ≤ 0. Any superharmonic function that is bounded below by a harmonic function for all points on the boundary of a ball are bounded below by the harmonic function for all points inside the ball. Similarly, if a supermartingale and a martingale have equivalent expectations for a given time, the history of the supermartingale tends to be bounded below by the history of the martingale. Roughly speaking, the prefix "super-" is consistent because the current observation Xn is greater than (or equal to) the conditional expectation E[Xn+1|X1,...,Xn]. Consequently, the current observation provides support from above the future conditional expectation, and the process tends to decrease in future time.

Examples of submartingales and supermartingales

- Every martingale is also a submartingale and a supermartingale. Conversely, any stochastic process that is both a submartingale and a supermartingale is a martingale.

- Consider again the gambler who wins $1 when a coin comes up heads and loses $1 when the coin comes up tails. Suppose now that the coin may be biased, so that it comes up heads with probability p.

- If p is equal to 1/2, the gambler on average neither wins nor loses money, and the gambler's fortune over time is a martingale.

- If p is less than 1/2, the gambler loses money on average, and the gambler's fortune over time is a supermartingale.

- If p is greater than 1/2, the gambler wins money on average, and the gambler's fortune over time is a submartingale.

- A convex function of a martingale is a submartingale, by Jensen's inequality. For example, the square of the gambler's fortune in the fair coin game is a submartingale (which also follows from the fact that Xn2 − n is a martingale). Similarly, a concave function of a martingale is a supermartingale.

Martingales and stopping times

A stopping time with respect to a sequence of random variables X1, X2, X3, ... is a random variable τ with the property that for each t, the occurrence or non-occurrence of the event τ = t depends only on the values of X1, X2, X3, ..., Xt. The intuition behind the definition is that at any particular time t, you can look at the sequence so far and tell if it is time to stop. An example in real life might be the time at which a gambler leaves the gambling table, which might be a function of his previous winnings (for example, he might leave only when he goes broke), but he can't choose to go or stay based on the outcome of games that haven't been played yet.

In some contexts the concept of stopping time is defined by requiring only that the occurrence or non-occurrence of the event τ = t be probabilistically independent of Xt + 1, Xt + 2, ... but not that it be completely determined by the history of the process up to time t. That is a weaker condition than the one appearing in the paragraph above, but is strong enough to serve in some of the proofs in which stopping times are used.

One of the basic properties of martingales is that, if  is a (sub-/super-) martingale and

is a (sub-/super-) martingale and  is a stopping time, then the corresponding stopped process

is a stopping time, then the corresponding stopped process  defined by

defined by  is also a (sub-/super-) martingale.

is also a (sub-/super-) martingale.

The concept of a stopped martingale leads to a series of important theorems, including, for example, the optional stopping theorem which states that, under certain conditions, the expected value of a martingale at a stopping time is equal to its initial value.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Balsara, N. J. (1992). Money Management Strategies for Futures Traders. Wiley Finance. p. 122. ISBN 0-471-52215-5.

- ↑ Mansuy, Roger (June 2009). "The origins of the Word "Martingale"" (PDF). Electronic Journal for History of Probability and Statistics 5 (1). Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- ↑ Grimmett, G.; Stirzaker, D. (2001). Probability and Random Processes (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-857223-9.

References

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Martingale", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- "The Splendors and Miseries of Martingales". Electronic Journal for History of Probability and Statistics 5 (1). June 2009. Entire issue dedicated to Martingale probability theory.

- Williams, David (1991). Probability with Martingales. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40605-6.

- Kleinert, Hagen (2004). Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics, Statistics, Polymer Physics, and Financial Markets (4th ed.). Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 981-238-107-4.

- Siminelakis, Paris (2010). "Martingales and Stopping Times: Use of martingales in obtaining bounds and analyzing algorithms" (PDF). University of Athens.

- Ville, Jean (1939). Étude critique de la notion de collectif. Monographies des Probabilités (in French) 3. Paris: Gauthier-Villars. Zbl 0021.14601. Review by Doob.

|

![\mathbf{E}_{\mathbf{P}} \left([Y_t-Y_s]\chi_F\right)=0,](../I/m/9a70e8a3b3451cfd6459f386323e8fb5.png)

![\begin{align}

E[Y_{n+1} \mid X_1,\dots,X_n] & = p (q/p)^{X_n+1} + q (q/p)^{X_n-1} \\[6pt]

& = p (q/p) (q/p)^{X_n} + q (p/q) (q/p)^{X_n} \\[6pt]

& = q (q/p)^{X_n} + p (q/p)^{X_n} = (q/p)^{X_n}=Y_n.

\end{align}](../I/m/9c16211e8caa92a8a5cdd7b8acbfe31d.png)

![{}E[X_{n+1}|X_1,\ldots,X_n] \ge X_n.](../I/m/eddd6a848d405b6518dd7af83464b691.png)

![{}E[X_t|\{X_{\tau} : \tau \le s\}] \ge X_s \quad \forall s \le t.](../I/m/40c23cd428c681738dc51a60552683cb.png)

![{}E[X_{n+1}|X_1,\ldots,X_n] \le X_n.](../I/m/fcd7050dc923445bc538bac0dfbd940a.png)

![{}E[X_t|\{X_{\tau} : \tau \le s\}] \le X_s \quad \forall s \le t.](../I/m/740e6c7fb56089943ec7f77a5e0b81bd.png)