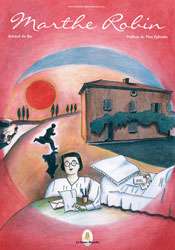

Marthe Robin

| Marthe Robin | |

|---|---|

|

Marthe Robin | |

| Born |

13 March 1902 Châteauneuf-de-Galaure |

| Died |

6 February 1981 (aged 78) Châteauneuf-de-Galaure |

Marthe Robin (born 13 March 1902 in Châteauneuf-de-Galaure, died on 6 February 1981) was a French Roman Catholic mystic and founder of the Foyers de Charité and a reported stigmatist.[1][2] She became bedridden when she was 21 years old, and remained so until her death.[3] According to witnesses she ate nothing for many years apart from receiving Holy Eucharist.[4] She is also reported to have seen apparitions of the Virgin Mary and of Christ.

A file of documents supporting her beatification was submitted to the diocesan authorities in 1987, and transmitted to the Vatican in 1996.[5] On 6 May 2010 a "Positio" was signed in Rome by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints. This file was made up of all the documents that support Marthe Robin's reputation for holiness. It culminated in her recognition for heroic virtues on 7 November 2014.[6]

Life

Childhood

Marthe Robin was born into a peasant farming family on 13 March 1902 in Châteauneuf-de-Galaure (Drôme, France),[7] in a hamlet called Les Moillés, which was locally known as "La Plaine". She was the sixth and last child of Joseph Robin d’Amélie-Célestine Chosson. She attended to the Châteauneuf-de-Galaure primary school, and stayed there until she was thirteen. She never took her end of primary school exams. She helped out on the family farm and participated in village life. Her personality is described by some witness as being "a happy young girl, open to the future, helpful, and sometimes mischievous..."..[8] In spite of the fact that her parents were non-practicing Catholics,[9] Marthe was drawn to prayer at an early age. She said: "J’ai toujours énormément aimé le Bon Dieu comme petite fille… J’ai toujours énormément prié dans ma vie" ("I always really loved God when I was a little girl. I have always prayed throughout my life").[10]

Sickness

In 1903, Marthe and her older sister, Clémence, both caught typhoid fever. Clémence died of it, and Marthe was close to death. After two months Marthe recovered, although she had fragile health throughout the rest of her childhood.

Marthe fell sick again on 1 December 1918. The doctors who examined her thought she had a brain tumor. She fell into a coma which lasted four days. When she came out of the coma, she seemed better for several weeks. But then the sickness got worse, until she was partially paralyzed. She also had eyesight problems, and lost her sight altogether for several months. In April–May 1921, she went into remission, but this was followed by several crises, which culminated in the definitive paraylsis of her lower body from May 1928 onwards.[11]

Marthe continued to live on the farm, and her family and friends became her carers. Like many sick people, she suffered from the incomprehension of those around her, including members of her family.[12] Her mobility problems, combined with hypersensitivity to light oblige her to become a recluse in a dark bedroom.[8]

An interpretation of her sickness has been given, on the basis of medical records gathered by the diocesan inquiry, and also a medical examination performed in 1942 by two doctors (Jean Dechaume, professor at Lyon Faculty of Medicine and a surgeon, André Ricard).[13] It seems as though Marthe may have been suffering from lethargic encephalitis,[14] also called von Economo disease, an inflammatory infection of the nervous system.

The trial of sickness that started in 1918 strengthened Marthe's faith. She did her best to bear it patiently, and tried to make herself useful to the family by doing needlework. Then, in 1925, she wrote an Act of abandon and love to the will of God.[15] She desired to consecrate herself to Christ and from then onwards loved the Eucharist more and more.[15]

Mystical phenomena

Marthe's spiritual life was also marked by mystical phenomena.[16][17][18] The testimonies of friends and family, priests, bishops and lay people who met her are recorded in the diocesans enquiry (1986–1996), and on the basis of this Bernard Peyrou, Postulator of the Cause for Beatification has written a biography of Marthe.[19] The authenticity of these testimonies in the eyes of the Catholic Church are currently being examined as part of the Cause of Beatification.

On 25 March 1922, according to the testimony of her sister Alice, Marth had a personal vision of the Virgin Mary.[20] Following the testimonies gathered by the 1986 Diocesan Enquiry, this vision was followed by others.[20] She reported that Christ appeared to her on the night of 4 December 1928. She confessed this vision to Père Faure, her parish priest, then took the decision to give her life entirely to God and to unite herself with his sufferings through prayer and love.[21] From then on, her spiritual life was more and more centered on the Passion of Christ and the Eucharist. She received regular visits from several local priests.[22]

From 1930 onwards, Marthe ate no food other than the consecrated host. This (unsought) fast lasted until her death fifty-one years later. Her stigmata first appeared in early October 1930.[23][24][25] In October–November 1931 she started to relive the Passion of Christ every Friday, and this too lasted until her death in 1981.[25][26] Many friends, family members and numerous priests witnessed this.[27][28]

Marthe herself pleaded discretion concerning these phenomena and encouraged Christians not to focus on them.[29][30] Five successive bishops of the diocese of Valence that Marthe belonged to, as well as being prudent,[31] all said they knew Marthe and that she had never come across as somebody to be mistrusted.[32]

Spiritual direction

On 3 December 1928, during a parish mission organized at Châteauneuf-de-Galaure, two Franciscan priests, Père Jean and Père Marie-Bernard, visited Marthe.[33] Père Marie-Bernard reassured her and talked to her about spiritual vocation. In 1928, she entered the Franciscan Third order.[34]

In the same year, Père Faure, her parish priest, became her spiritual director, a role that he did not relish because he could not personally relate to mystical experience.[35] In 1936, Marthe met Georges Finet, a priest from Lyon who took over Père Faure's role.[36][37] Marthe's relationship with Père Finet was close and continued for the rest of her life.[38]

Last days, death and funeral

In early February 1981, Marthe had a coughing attack that became more and more acute. On Thursday 5 February, she had a high fever. That evening, like every Thursday, she prayed to be united to Christ in his Passion. Members of the foyer said the Rosary around her bed, then left her alone. The following day, at about 5 p.m., when Pere Finet went into her room, he found Marthe unconscious on the floor, near her bed. She had died, probably of exhaustion, in the early hours of Friday 6 February. Père Colon, a medical doctor, and Dr Andolfatto, the doctor of Châteauneuf, confirmed her death.[39] No autopsy was carried out.[40] Her funeral took place on 12 February, in the sanctuary at Châteauneuf-de-Galaure, in the presence of four bishops and over 200 priests.[41] Her tomb is in the cemetery of St Bonnet.

Influence and posterity

Ministry to others

Although she was bedridden, Marthe met countless people. She participated in the life of her diocese and her village as well as she was able. In October 1934, at her initiative, a girl’s school was founded at Châteauneuf-de-Galaure. It developed rapidly.[42] With the help of George Finet, she also founded the first Foyer de Charité. The foyer organized five-day retreats, and 2,000 retreatants participated annually.[43] Most of them, at the end of the retreat, went to visit Marthe. It is estimated that, in fifty years, she individually met more than 100,000 people, including hundreds of priests and many bishops.[44] Some visitors went to her seeing advice about their lives. In general, she did not give specific, categorical advice. Rather, she asked questions, made suggestions, prevented visitors from going off the subject, and let them reach their own conclusions.[45] She was also a prolific letter writer, which she managed by dictating to a secretary.[46]

Marthe Robin received visits from people such as Jean Guitton, Father Garrigou-Lagrange, Marcel Clément, Estelle Satabin, Father Thomas Philippe, Sister Magdeleine (1898-1989), founder of the Petites Sœurs de Jésus, Father Perrin, founder of the secular institute Caritas Christi, Father Henri Caffarel, founder of the Equipes Notre-Dame, sister Marie Dupont-Caillard, founder of the Sœurs et Frères de Bethléem.[47][48] She also followed and supported, to differing degrees, the setting up of various of the new Catholic communities and associations that were founded in France during the 20th century,[49] for example the Communauté Saint Jean, the Communauté de l'Emmanuel, the Communauté des Béatitudes, the Frères Missionnaires des Campagnes, founded by Father Epagneul, a Dominican, and the Association Claire Amitié, founded by Thérèse Cornille. She also met Father Eberhard, the founder of Notre-Dame de la Sagesse, Sister Norbert-Marie, who inspired the foundation of the Petites Sœurs de Nazareth, and Mère Myriam, who founded the communauté des Petites Sœurs de la Compassion, d'Israël et de Saint-Jean in 1982.[48][50]

The number of visitors going to pray at the farmhouse on La Plaine, where Marthe Robin lived, doubled between 2001 and 2011, reaching 40,000 a year.[51]

Foyers de Charité

In 1936, Marthe Robin founded the Foyers de Charité at Châteauneuf-de-Galaure.[52][53] Lay people participated in the life of this foyer, under the supervision of a priest. This involvement of lay people was unusual in pre-Vatican II Catholicism. Since then, a total of 75 these communities have been founded in 44 countries,[54] either directly by Marthe herself or inspired by her example. In 1984, the Foyers de Charity were officially recognized by the Catholic Church as an Association de fidèles de droit international, under the Pontifical Council for laypeople.[55]

The Foyers de Charité have in turn influenced the founders of various communities within the charismatic renewal, including the Community of St. John, the Emmanuel Community, and the Community of the Beatitudes.

Beatification process

In 1986, a diocesan inquiry was opened to investigate the possibility of Marthe's beatifcation.[5][56][57] Two religious experts, a theologian and a historian, were entrusted with the case in 1988. The Vatican granted a Nihil obstat in 1991. Between 1988 and 1996, more than 120 witnesses and experts were consulted. From 1993 to 1995, a critical biography was written for the Congregation for the cause of saints.[58] A file of 17,000 pages was submitted to the Vatican in 1996.[57][59] A decree of the Congregation for the cause of saints dated 24 April 1998 agreed that the diocesan inquiry was valid. The Positio, a summary of 2000 pages of the beatification file which lays out the results of the diocesan inquiry was submitted on 6 May 2010, for a commission of theologians to study; a meeting of these experts took place on 11 December 2012.[60][61][62] The "heroic virtues" of Marthe Robin were recognized on 7 November 2014 by Pope Francis (Press release of the French Bishops). She is therefore declared venerable and recognition of a miracle could open the door to her beatification.

Medical and skeptical opinion

The philosopher Jean Guitton claimed that Marthe was offered the possibility of medical analysis at a clinic for several months in order to prove to skeptics that her apparent inability to eat was not some elaborate hoax. But Marthe declined, saying "Do you really think that will convince people? Those who don’t believe it will not believe it any more because of that.".[63] Consequently, there is no clinical proof of Marthe Robin’s fifty year fast. Guitton deplored that "in this present era, prudence requires us to suppose that such phenomena can only be explained by autosuggestion, hysteria, or mental illness rather than by a noble and transcendent cause."

Many scientific sceptics consider that Marthe’s mystic manifestations, particularly her long fast, were simply an elaborate hoax[64] and in the scientific world, even though numerous doctors at the time ruled out this possibility[65] many others diagnosed it as hysteria. For example:

- Gonzague Mottet, for whom "l’avalanche de troubles qui n’ont en commun que leur appartenance à la classique sémiologie des manifestations hystériques est assez caricaturale pour nous permettre de porter le diagnostic de conversion hystérique." ("the avalanche of [Marthe Robin’s] disorders, which have in common only their listing under the classic semiology of hysterical manifestations, are sufficiently ridiculous to allow a diagnosis of hysterical conversion."),[66]

- Jean Lhermitte, for whom, more generally, these phenomena are "des accidents de nature névrosique ou mieux psychonévrosique à caractère hystérique." ("accidents of a neurotic, or rather psychoneurotic, nature with a hysterical character"),[67]

- Pierre Janet, for whom "les sainte Hildegarde, les Marie Chantal, les Catherine Emmerich et bien d'autres avaient tout simplement des attaques de catalepsie" ("People like Saint Hildegarde, Marie Chantal, Catherine Emmerich and many others simply had attacks of catalepsy")[68]

- the sceptic priest Herbert Thurston who declared that he had "encore jamais vu de cas de stigmatisation chez un sujet dépourvu de symptômes névrotiques." ("never yet seen a case of stigmatization in a patient who did not also have neurotic symptoms"),[69]

- Jean-Martin Charcot, who diagnoses all extraordinary manifestations — long fasts, miraculous healings, demonic possession, levitation, apparitions — as hysteria[70]

- Herbert Thurston, for whom "le cas de Thérèse Neumann présente des analogies frappantes avec ce que vivait l’hystérique américaine Mollie Fancher" ("the case of Thérèse Neumann bears striking similarity to the experience of the American hysteric Mollie Fancher"),[70] (The same diagnosis of "grave hysteria" was applied to Thérèse Neumann in 1938).[71]

- According to an inquiry by the philosophy professor François de Muizon, worn shoes and a basin containing melæna were found in the Marthe Robin’s room, which would seem to indicate that she could move more than was usually reported[72][73]

- According to François de Muizon, no one has ever been able to explain her survival in spite of her long fast [73][74] At the same time, the author considers it most unfortunate that no autopsy was ever done.[73]

See also

- Stigmata

- Francis of Assisi

- Padre Pio

- Alexandrina of Balasar

- Maria Domenica Lazzeri

- Marie Rose Ferron

- Lydwine of Schiedam

References

- ↑ Freze, Michael. 1993, They bore the wounds of Christ, OSV Publishing ISBN 0-87973-422-1 p.284

- ↑ Freze, Michael. 1993, Voices, Visions, and Apparitions, OSV Publishing ISBN 0-87973-454-X p.252

- ↑ Langan, Thomas. The Catholic tradition 1998 ISBN 0-8262-1183-6 p.446

- ↑ Gallagher, Jim. The Voice of Padre Pio, 1996

- 1 2 Peyrous (2006), p. 10

- ↑ "Marthe Robin Declared 'Venerable' by the Pope", Press Release, Site officiel sur Marthe Robin, 7 November 2014, accessdate = 8 November 2014

- ↑ "Marthe Robin's life", the Foyers de Charité

- 1 2 Peyrous (2006), pp. 21–29

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), p. 27

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), p. 26

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 34–35

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 37–42

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 35–36, 75, 149

- ↑ Antier (1996), pp. 401–407

- 1 2 Peyrous (2006), p. 47

- ↑ Raymond Peyret, Marthe Robin, l’offrande d’une vie, Salvator, 2007, 334 pages.

- ↑ Antier (1996)

- ↑ Roland Maisonneuve, Les Mystiques chrétiens et leurs visions de Dieu un et trine, Paris, Cerf, 2000, 350 pages.

- ↑ Peyrous (2006)

- 1 2 Peyrous (2006), p. 42

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 55–56

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 70–71

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), p. 72

- ↑ J. Barbier, Trois stigmatisés de notre temps—Thérèse Neumann, le Padre Pio, Marthe Robin, éd. Tequi, 1987

- 1 2 Marthe Robin Souffrance, lumière et charité Serge Laporte. Dossier Les mystiques, Le Monde des Religions, mai-juin 2007, page 37.

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 73–75

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 187–188

- ↑ , Marthe Robin, témoignage d’un psychiatre, Paris, éd. de l’Emmanuel, 1996.

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), p. 265

- ↑ Justine Louis, "L’Église catholique face à l’extraordinaire chrétien depuis Vatican II", thèse de doctorat sous la direction de Régis Ladous, Université Jean Moulin Lyon 3, Institut d’Histoire du christianisme, 2008, p. 257

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), p. 150

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 149–150, 307

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), p. 53

- ↑ (French) "Marthe Robin Souffrance, lumière et charité" Serge Lafitte, in "Les mystiques", Le Monde des Religions, May–June 2007, page 37

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 55–56, 70–72

- ↑ Christine Pina, Voyage au pays des charismatiques français, éd. de l’Atelier et éd. Ouvrières, Paris, 2001, p. 43

- ↑ Claire Lesetegrain, Le P. Jacques Ravanel, fondateur du foyer de La Flatière, est mort, lacroix.com, 12 October 2011.

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 115–131

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 338–339

- ↑ de Muizon (2011)

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), p. 342

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 96–97, 135–136

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), p. 221

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 307–309

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), p. 259

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 268, 323–324

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 296–312

- 1 2 Les communautés nouvelles - Nouveaux visages du catholicisme français Olivier Landron, Ed. Cerf Histoire, page 123–126

- ↑ Peyrous (2006)

- ↑ This community was disbanded by the Catholic Church in 2005 (Le Bien public, 20 March 2005).

- ↑ Marthe Robin attire toujours des foules, la-croix.com, 4 février 2011.

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), pp. 133–143

- ↑ Vatican website

- ↑ Deux anniversaires pour les Foyers de charité, Rédaction en ligne, La Croix, 3 février 2011.

- ↑ Peyrous (2006), p. 334

- ↑ (French) "Entretien avec le postulateur de la cause de béatification de Marthe Robin", Catholique.org news.catholique.org Retrieved 24 June 2009

- 1 2 Entretien avec le postulateur de la cause de béatification de Marthe Robin sur le site zenit.org

- ↑ "Marthe Robin, un long chemin vers une possible béatification (par Fr.X. Maigre)". La Croix (in French). 7 August 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ↑ Anniversaire de la mort de Marthe Robin sur le site new.catholiques.org

- ↑ Nouvelles de la cause de béatification de Marthe Robin sur le site foyer-de-charite.com

- ↑ État d'avancement de la cause de Marthe Robin, site newsaints.faithweb.com, consulté le 28 avril 2014.

- ↑ Une année de célébrations autour de Marthe Robin, Site de la Conférence des évêques de France, 4 février 2011.

- ↑ Portrait de Marthe Robin par Jean Guitton, Grasset, 1999, p.

- ↑ Template:Référence incomplète

- ↑ Blanche, Marthe, Camille, Notes Sur Trois Mystiques par Jean Vuilleumier, L'âge d'homme, 1996, p. 42 : "Les spécialistes ... ont écarté la supercherie ou la simulation ... ils ne remarquaient rien qui puisse laisse penser à des perturbations psychiques ... aucun signe de débilité mentale, aucune manifestation délirante." ("Specialists have ruled out any possibility of hoax or simulation (…) they did not observe any signs of psychic perturbations (…), no sign of mental debility, no delirious manifestations")

- ↑ Marthe Robin, la stigmatisée de la Drôme. Étude d’une mystique du XXe siècle, Gonzague Mottet, Toulouse, Erès, 1989, p. 84.

- ↑ "Marie-Thérèse Noblet (1889-1930), considérée du point de vue neurologique", Jean Lhermitte, p. 207.

- ↑ L’automatisme psychologique, Essai de psychologie expérimentale sur les formes inférieures de l'activité humaine (1889) dans Pierre Janet, Encyclopédie psychologique, L’Harmattan, 2005.

- ↑ Herbert Thurston, Les phénomènes physiques du mysticisme, p. 246.

- 1 2 Stigmatisés, hystériques : des "symptômes" similaires? sur le site de l'Université Jean Moulin, Lyon 3.

- ↑ Théo livre 1 - Les saints par Michel Dubost, Stanislas Lalanne, Mame, 2011.

- ↑ de Muizon (2011), p. 74: "Elle ne peut plus ni manger ni boire."

- 1 2 3 Émission Au cœur de l'Histoire sur europe1.fr

- ↑ de Muizon (2011), pp. 76–79: "Comment survit-elle ?"

Sources

- Antier, Jean-Jacques (1996) [1991]. Marthe Robin, le voyage immobile. Perrin. ISBN 9782915313635.

- de Muizon, François (2011). Marthe Robin, le mystère décrypté. Éd. Presses de la Renaissance.

- Peyrous, Bernard (2006). Vie de Marthe Robin. Éditions de l'Emmanuel/Foyer de Charité editions. ISBN 2-915313-63-6.

Bibliography

- Marcel Clément, Pour entrer chez Marthe, Fayard, 1993.

- Jean Guitton, Portrait de Marthe Robin, Grasset, 1985 ; réédition Le Livre de Poche, 1999

- Henri-Marie Manteau-Bonamy, Marthe Robin sous la conduite de Marie, 1925-1932, éd. Saint-Paul, 1995, 191 pages.

- Jacques Ravanel, Le secret de Marthe Robin, Presses de la Renaissance, 2008

- Raymond Peyret, Marthe Robin: The Cross and the Joy Alba House, 1983 ISBN 0-8189-0464-X

External links

- (French) Official site about Marthe Robin by the Foyers de Charité (in French).

- Portrait of Marthe Robin by Marchand Conférence des évêques de France (in French).

|