Marshall–Lerner condition

The Marshall–Lerner condition (after Alfred Marshall and Abba P. Lerner) refers to the condition that an exchange rate devaluation or depreciation will only cause a balance of trade improvement if the absolute sum of the long-term export and import demand elasticities is greater than unity.[1] If the domestic currency devalues, imports become more expensive and exports become cheaper due the change in relative prices. Initially, there will be a deterioration of the trade balance which can be attributed to lags in recognition of the changed situation, lags in the decision to change real variables, lags in delivery time, lags in replacement of inventories and materials and lags in production.[2] These lags ensure that the demand for exports remains inelastic in the short term. In the long-term though, when the prices become flexible, there will be a positive quantity effect on the balance of trade because domestic consumers will buy fewer imports and foreign consumers will buy more of our exports; but offsetting this is a negative cost effect on the balance of trade, since the relative cost of imports will be higher. Whether the net effect on the trade balance is positive or negative depends on whether or not the quantity effect outweighs the cost effect; if the quantity effect is greater, then it is said that the Marshall–Lerner condition is met. Essentially, the Marshall–Lerner condition is an extension of Marshall's theory of the price elasticity of demand to foreign trade.

Formally, the condition states that, for a currency devaluation to have a positive impact on trade balance, the sum of price elasticity of exports and imports (in absolute value) must be greater than 1. The net effect on the trade balance will depend on price elasticities. If goods exported are elastic to price, their quantity demanded will increase proportionately more than the decrease in price, and total export revenue will increase. Similarly, if goods imported are elastic, total import expenditure will decrease. Both will improve the trade balance.

Empirically, it has been found that trade in goods tends to be inelastic in the short term, as it takes time to change consuming patterns and trade contracts.[3] Thus, the Marshall–Lerner condition is not met, and a devaluation is likely to worsen the trade balance initially. In the long term, consumers will adjust to the new prices, and trade balance will improve. This effect is called the J-curve effect. For example, assume a country is a net importer of oil and a net producer of ships. Initially, the devaluation immediately increases the price of oil, and as consumption patterns remain the same in the short term, an increased sum is spent on imported oil, worsening the deficit on the import side. Meanwhile, it takes some time for the shipbuilder's sales department to exploit the lower price and secure new contracts. Only the funds acquired from previously agreed contracts, now devalued by the currency devaluation, are immediately available, again worsening the deficit on the export side.

Mathematical derivation

Here  is defined as the price of one unit of foreign currency in terms of the domestic currency.

is defined as the price of one unit of foreign currency in terms of the domestic currency.

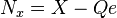

Using this definition, the trade balance denominated in domestic currency (with domestic and foreign prices normalized to one) is given by:

where X denotes exports, and Q imports.

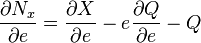

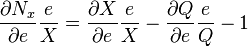

Differentiating with respect to e gives:

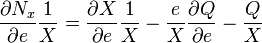

Dividing through by X:

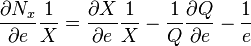

At equilibrium,  . Therefore:

. Therefore:

Multiplying through by e:

Which can be expressed as

where  and

and  are common notation for the elasticity of exports and imports with respect to the exchange rate respectively.

are common notation for the elasticity of exports and imports with respect to the exchange rate respectively.

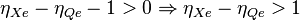

In order for a fall in the relative value of a country's currency (i.e. a rise in e using the above definition) to have a positive effect on that country's trade balance, the left hand side of the equation must be positive (i.e. for a rise in e to cause a rise in  ).

).

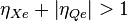

Therefore:

Which can be written as:

References

- ↑ Davidson, Paul (2009), The Keynes Solution: The Path to Global Economic Prosperity, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 125, ISBN 978-0-230-61920-3.

- ↑ Junz H. and Rhomberg R. 1973 Price Competitiveness in Export Trade Among Industrial Countries. American Economic Review, Paper and Proceedings, (412-418)

- ↑ Bahmani-Oskooee *, M.; Ratha, A. (2004). "The J-Curve: A literature review". Applied Economics 36 (13): 1377. doi:10.1080/0003684042000201794.

Further reading

- Rose, Andrew K. (1991). "The role of exchange rates in a popular model of international trade: Does the ‘Marshall–Lerner’ condition hold?". Journal of International Economics 30 (3–4): 301–316. doi:10.1016/0022-1996(91)90024-Z..