Mariana Trench

Coordinates: 11°21′N 142°12′E / 11.350°N 142.200°E

The Mariana Trench or Marianas Trench[1] is the deepest part of the world's oceans. It is located in the western Pacific Ocean, to the east of the Mariana Islands. The trench is about 2,550 kilometres (1,580 mi) long but has an average width of only 69 kilometres (43 mi). It reaches a maximum-known depth of 10,994 m (± 40 m) or 6.831 mi (36,070 ± 131 ft) at a small slot-shaped valley in its floor known as the Challenger Deep, at its southern end,[2] although some unrepeated measurements place the deepest portion at 11,030 metres (36,190 ft).[3]

At the bottom of the trench the water column above exerts a pressure of 1,086 bars (15,750 psi) (over 1000 times the standard atmospheric pressure at sea level). At this pressure, the density of water is increased by 4.96%, making 95 litres of water under the pressure of the Challenger Deep contain the same mass as 100 litres at the surface. The temperature at the bottom is 1 to 4 °C.[4]

The trench is not the part of the seafloor closest to the center of the Earth. This is because the Earth is not a perfect sphere; its radius is about 25 kilometres (16 mi) less at the poles than at the equator.[5] As a result, parts of the Arctic Ocean seabed are at least 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) closer to the Earth's center than the Challenger Deep seafloor.

Xenophyophores have been found in the trench by Scripps Institution of Oceanography researchers at a record depth of 10.6 km (6.6 mi) below the sea surface.[6] On 17 March 2013, researchers reported data that suggested microbial life forms thrive within the trench.[7][8]

Names

The Mariana Trench is named for the nearby Mariana Islands (in turn named Las Marianas in honor of Spanish Queen Mariana of Austria, widow of Philip IV of Spain). The islands are part of the island arc that is formed on an over-riding plate, called the Mariana Plate (also named for the islands), on the western side of the trench.

Geology

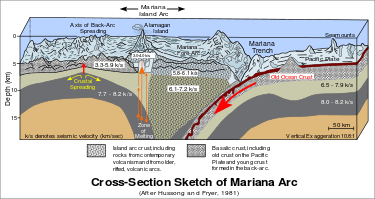

The Mariana Trench is part of the Izu-Bonin-Mariana subduction system that forms the boundary between two tectonic plates. In this system, the western edge of one plate, the Pacific Plate, is subducted (i.e., thrust) beneath the smaller Mariana Plate that lies to the west. Crustal material at the western edge of the Pacific Plate is some of the oldest oceanic crust on earth (up to 170 million years old), and is therefore cooler and more dense; hence its great height difference relative to the higher-riding (and younger) Mariana Plate. The deepest area at the plate boundary is the Mariana Trench proper.

The movement of the Pacific and Mariana plates is also indirectly responsible for the formation of the Mariana Islands. These volcanic islands are caused by flux melting of the upper mantle due to release of water that is trapped in minerals of the subducted portion of the Pacific Plate.

Measurements

The trench was first sounded during the Challenger expedition in 1875, which recorded a depth of 4,475 fathoms (8.184 km).[9] In 1877 a map was published called Tiefenkarte des Grossen Ozeans by Petermann, which showed a Challenger Tief at the location of that sounding. In 1899 USS Nero, a converted collier, recorded a depth of 5269 fathoms (9,636 m, 31,614 ft).[10] Challenger II surveyed the trench using echo sounding, a much more precise and vastly easier way to measure depth than the sounding equipment and drag lines used in the original expedition. During this survey, the deepest part of the trench was recorded when the Challenger II measured a depth of 5,960 fathoms (10,900 m, 35,760 ft) at 11°19′N 142°15′E / 11.317°N 142.250°E, known as the Challenger Deep.[11]

In 1957, the Soviet vessel Vityaz reported a depth of 11,034 m (36,201 ft), dubbed the Mariana Hollow.[3]

In 1962, the surface ship M.V. Spencer F. Baird recorded a maximum depth of 10,915 m (35,840 ft), using precision depth gauges.

In 1984, the Japanese survey vessel Takuyō (拓洋) collected data from the Mariana Trench using a narrow, multi-beam echo sounder; it reported a maximum depth of 10,924 m, also reported as 10,920 ± 10 metres.[12]

Remotely Operated Vehicle KAIKO reached the deepest area of Mariana trench and made the deepest diving record of 10,911 m on March 24, 1995.[13]

During surveys carried out between 1997 and 2001, a spot was found along the Mariana Trench that had depth similar to that of the Challenger Deep, possibly even deeper. It was discovered while scientists from the Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology were completing a survey around Guam; they used a sonar mapping system towed behind the research ship to conduct the survey. This new spot was named the HMRG (Hawaii Mapping Research Group) Deep, after the group of scientists who discovered it.[14]

On 1 June 2009 sonar mapping of the Challenger Deep by the Simrad EM120 sonar multibeam bathymetry system for deep water (300–11,000 m) mapping aboard the RV Kilo Moana (mothership of the Nereus vehicle), has indicated a spot with a depth of 10,971 m (35,994 ft). The sonar system uses phase and amplitude bottom detection, with an accuracy of better than 0.2% of water depth across the entire swath (implying the depth figure is accurate to less than ± 22 metres).[15][16]

In 2011, it was announced at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting that a US Navy hydrographic ship equipped with a multibeam echosounder conducted a survey which mapped the entire trench to 100 m resolution.[2] The mapping revealed the existence of four rocky outcrops thought to be former seamounts.[17]

The Mariana Trench is a site chosen by researchers at Washington University and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in 2012 for a seismic survey to investigate the subsurface water cycle. Using both ocean-bottom seismometers and hydrophones the scientists are able to map structures as deep as 60 mi (97 km) beneath the surface.[18]

Descents

Four descents have been achieved. The first was the manned descent by Swiss-designed, Italian-built, United States Navy-owned bathyscaphe Trieste which reached the bottom at 1:06 pm on 23 January 1960, with Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard on board.[11][20] Iron shot was used for ballast, with gasoline for buoyancy.[11] The onboard systems indicated a depth of 11,521 m (37,799 ft), but this was later revised to 10,916 m (35,814 ft).[21] The depth was estimated from a conversion of pressure measured and calculations based on the water density from sea surface to seabed.[20]

This was followed by the unmanned ROVs Kaikō in 1996 and Nereus in 2009. The first three expeditions directly measured very similar depths of 10,902 to 10,916 m.

The fourth was made by Canadian film director James Cameron in 2012. On 26 March, he reached the bottom of the Mariana Trench in the submersible vessel Deepsea Challenger.[22][23][24]

Planned descents

As of February 2012, at least three other teams are planning piloted submarines to reach the bottom of the Mariana Trench. These include: Triton Submarines, a Florida-based company that designs and manufactures private submarines, for which a crew of three will take 120 minutes to reach the seabed;[25] Virgin Oceanic, sponsored by Richard Branson's Virgin Group, designed by Graham Hawkes, and piloted by Chris Welsh, for which the solo pilot will take 140 minutes to reach the seabed;[26] and DOER Marine, a marine technology company, based near San Francisco and set up in 1992, for which a crew of two or three will take 90 minutes to reach the seabed.[27]

Life

The expedition conducted in 1960 observed (with great surprise because of the high pressure) at the bottom large living creatures such as a flatfish about 30 cm (1 ft) long,[21] and shrimp.[28] According to Piccard, "The bottom appeared light and clear, a waste of firm diatomaceous ooze".[21] Many marine biologists are now skeptical of the supposed sighting of the flatfish, and it is suggested that the creature may instead have been a sea cucumber.[29][30]

During the second expedition, the unmanned vehicle Kaikō collected mud samples from the seabed.[31] Tiny organisms were found to be living in those samples.

In July 2011, a research expedition deployed untethered landers, called dropcams, equipped with digital video and lights to explore this region of the deep sea. Amongst many other living organisms, some gigantic single-celled amoebas with a size of more than 4 in (10 cm), belonging to the class of xenophyophores were observed.[32] Xenophyophores are noteworthy for their size, their extreme abundance on the seafloor and their role as hosts for a variety of organisms.

In December 2014, a new species of snailfish was discovered at a depth of 8,145 m (26,722 ft), breaking the previous record for the deepest living fish seen on video.[33] Several other new species were also filmed, including huge crustaceans known as supergiants.[33]

Possible nuclear waste disposal site

Like other oceanic trenches, the Mariana Trench has been proposed as a site for nuclear waste disposal,[34][35] in the hope that tectonic plate subduction occurring at the site might eventually push the nuclear waste deep into the Earth's mantle. However, ocean dumping of nuclear waste is prohibited by international law.[34][35][36] Furthermore, plate subduction zones are associated with very large megathrust earthquakes, the effects of which are unpredictable and possibly adverse to the safety of long-term disposal.[35] Also, disposal of nuclear wastes may cause havoc in the hadopelagic ecosystems.

See also

- Marianas Trench Marine National Monument, United States national monument at the trench. This National Monument protects 95,216 square miles (60,938,240 acres) of submerged lands and waters of the Mariana Archipelago. It includes some of the Mariana Trench, but not the deepest part, the Challenger Deep, which lies just outside the monument area.

Notes

- ↑ Variant according to the U.S. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- 1 2 "Scientists map Mariana Trench, deepest known section of ocean in the world". The Telegraph (Telegraph Media Group). 7 December 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- 1 2 "Mariana Trench". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ infoplease.com – The Temperature in the Mariana Trench, read 2012-05-13

- ↑ David R. Williams (17 November 2010).Earth Fact Sheet. National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ "Giant amoeba found in Mariana Trench – 6.6 miles beneath the sea". Los Angeles Times. 26 October 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ Choi, Charles Q. (17 March 2013). "Microbes Thrive in Deepest Spot on Earth". LiveScience. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Glud, Ronnie; Wenzhöfer, Frank; Middleboe, Mathias; Oguri, Kazumasa; Turnewitsch, Robert; Canfield, Donald E.; Kitazato, Hiroshi (17 March 2013). "High rates of microbial carbon turnover in sediments in the deepest oceanic trench on Earth". Nature Geoscience. Bibcode:2013NatGe...6..284G. doi:10.1038/ngeo1773. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "About the Mariana Trench – DEEPSEA CHALLENGE Expedition". Deepseachallenge.com. 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- ↑ Theberge, A. (24 March 2009). "Thirty Years of Discovering the Mariana Trench". Hydro International. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 "The Mariana Trench – Exploration". marianatrench.com.

- ↑ Tani, S. "Continental shelf survey of Japan" (PDF). Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ↑ Development and Construction of Launcher System of 10000m‐Class Remotely Operated Vehicle KAIKO Mitsubishi Heavy Industry

- ↑ Whitehouse, David (16 July 2003). "Sea floor survey reveals deep hole". BBC News. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ↑ "Daily Reports for R/V KILO MOANA June and July 2009". University of Hawaii Marine Center.

- ↑ "Inventory of Scientific Equipment aboard the R/V KILO MOANA". University of Hawaii Marine Center.

- ↑ Duncan Geere (7 February 2012). "Four 'bridges' span the Mariana Trench". Wired (Condé Nast Digital). Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ "Seismic Survey at the Mariana Trench Will Follow Water Dragged Down Into the Earth's Mantle". ScienceDaily. 22 March 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ Strickland, Eliza (2012-02-29). "Don Walsh Describes the Trip to the Bottom of the Mariana Trench – IEEE Spectrum". Spectrum.ieee.org. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- 1 2 "Mariana Trench". Earthquake Hazards Program. U.S. Geological Survey. 21 October 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) webpage. Section "1960 – Man at the Deepest Depth"

- ↑ AP Staff (25 March 2012). "James Cameron has reached deepest spot on Earth". MSNBC. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ↑ Broad, William J. (25 March 2012). "Filmmaker in Submarine Voyages to Bottom of Sea". New York Times. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ↑ Than, Ker (25 March 2012). "James Cameron Completes Record-Breaking Mariana Trench Dive". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ↑ "Triton Submarines". Tritonsubs.com. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ "Virgin Oceanic". Virgin Oceanic. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ "DOER Marine". DOER Marine. 20 December 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ "Bathyscaphe Trieste | Mariana Trench | Challenger Deep". Geology.com. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ↑ "James Cameron dives deep for Avatar", Guardian, 18 January 2011

- ↑ "James Cameron heads into the abyss", Nature, 19 March 2012

- ↑ Woods, Michael; Mary B. Woods (2009). Seven Natural Wonders of the Arctic, Antarctica, and the Oceans. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 13. ISBN 0-8225-9075-1. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ↑ "Giant amoebas discovered in the deepest ocean trench". Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- 1 2 "New record for deepest fish". BBC. 19 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- 1 2 Hafemeister, David W. (2007). Physics of societal issues: calculations on national security, environment, and energy. Berlin: Springer. p. 187. ISBN 0-387-95560-7.

- 1 2 3 Kingsley, Marvin G.; Rogers, Kenneth H. (2007). Calculated risks: highly radioactive waste and homeland security. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate. pp. 75–76. ISBN 0-7546-7133-X.

- ↑ "Dumping and Loss overview". Oceans in the Nuclear Age. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mariana Trench. |

- Mariana Trench Dive (25 March 2012) – Deepsea Challenger.

- Mariana Trench Dive (23 January 1960) – Trieste (Newsreel).

- Mariana Trench Dive (50th Anniv) – Trieste – Capt Don Walsh.

- Mariana Trench – To Scale.

- Mariana Trench – Maps (Google).

- NOAA – Ocean Explorer (Ofc Ocean Exploration & Rsch).

- NOAA – Ocean Explorer – Multimedia – Mariana Arc (podcast).

- NOAA – Ocean Explorer – Video Playlist – Ring of Fire (2004–2006).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|