Mariam-uz-Zamani

| Rajkumari Heer Kunwari | |

|---|---|

| Empress Consort of the Mughal Empire | |

Artistic depiction of Mariam-uz-Zamani alias Harka Bai | |

| Reign | 6 February 1562 – 27 October 1605 |

| Born |

5 October 1542 Amer, India |

| Died |

19 May 1623 (aged 81)[1][2] Agra, India[3] |

| Burial | Tomb of Mariam-uz-Zamani, Sikandra, Agra[1] |

| Consort | Akbar |

| Issue | Jahangir |

| House | Kachwahas of Amer |

| Father | Raja Bharmal |

| Religion | Hinduism |

Mariam-uz-Zamani Begum, also known as Heer Kunwari, Hira Kunwari or Harka Bai, (5 October 1542 – 19 May 1623) was an Empress of the Mughal Empire. She was the first and chief Rajput wife of Emperor Akbar, and the mother of the next Mughal Emperor, Jahangir.[4][5][6] She was also the grandmother of the following Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan.[7]

Mariam-Uz-Zamani was referred to as the Queen Mother[8] of Hindustan, during the reign of the Great Mughal,[9] Emperor Akbar and also during her son Emperor Jahangir's reign. She was the longest serving Hindu Mughal Empress. Her tenure, from 6 February 1562 to 27 October 1605, is that of over 43 years.

Her marriage to Akbar led to a gradual shift in his religious and social policy.[10] Akbar's marriage with Rajkumari Heer Kunwari was a very important event in Mughal history. She is widely regarded in modern Indian historiography as exemplifying Akbar's and the Mughal's tolerance of religious differences and their inclusive policies within an expanding multi-ethnic and multi-denominational empire.[11]

Family

Heer Kunwari (also called Harka bai was born a Rajput princess (Rajkumari) and was the eldest daughter of Raja Bharmal,[12][13][14][15] of Amer (modern day Jaipur). She was the granddaughter of Raja Prithvi Singh of Amer. Rajkumari Heer Kunwari was also the sister of Raja Bhagwan Das of Amer, and the aunt of Raja Man Singh I of Amer,[16] who later became one of the Nine Jewels (Navaratnas) in the court of Akbar. Later, both occupied high offices in Akbar's court.

Marriage

Akbar's marriage with Heer Kunwari had far-reaching results. It led Akbar to take a much more favorable view of Hinduism and his Hindu subjects.[17] In a marriage of political alliance, Heer Kunwari was married to Akbar on 6 February 1562 at Sambhar near Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. She was his third wife after Ruqaiya Sultan Begum and Salima Sultan Begum. Heer Kunwari, as mother of the heir-apparent, took precedence over all the other wives of Akbar.[18]

In the beginning of 1569, Akbar was gladdened by the news that his first Hindu consort, Heer Kunwari, was expecting a child, and that he might hope for the first of the three sons promised by Sheikh Salim Chisti, a reputed holy man who lived at Sikri. An expectant Heer was sent to Sheikh's humble dwelling at Sikri during the period of her pregnancy. On 30 August 1569, the boy was born and received the name Salim, in acknowledgement of his father's faith in the efficacy of the holy man's prayers.[19]

Heer Kunwari was honoured with the title Mariam-uz-Zamani ("Mary of the Age") after she gave birth to Jahangir. Despite her being a non-Muslim wife, she held great respect and honour in the Mughal household.[20]

Her title, Mariam-uz-zamani, 'the Mary of the Age', has been mistaken sometimes with Akbar's mother, whose title was Mariam-makani, 'dwelling with Mary'.[21] Apart from the title of Mariam-uz-Zamani, Heer also held the title of Wali Nimat Begam which literally means the Gift of God. She held this title throughout her lifetime and even issued farmans (official documents) using this title.[22]

Akbar's marriage with Heer, later Mariam-uz-Zamani, produced important effects on both on his personal rule of life and on his public policy.[23][24][25][26] The custom of Hindu rulers offering their daughters for marriage to Muslim rulers, though not common, had been prevalent in the country for several centuries. Yet Akbar's marriage to princess of Amber/Amer is significant, as an early indication of his evolving policy of religious eclecticism.[27] The marriage with the Amer princess secured the powerful support of her family throughout the reign, and offered a proof manifest to all the world that Akbar had decided to be the Badshah or Shahenshah of his whole people i.e. Hindus as well as Muslims.[28]

Akbar took other Rajput princesses in marriage. The rajas had much to gain from the link to imperial family. Akbar made such marriages respectable for rajputs.[29]

Her niece, Manbhawati Bai or Manmati bai, daughter of her brother Bhagwan Das, married Prince Salim on 13 February 1585. Man bai later became mother to Prince Khusrau Mirza[30][31] and was awarded the title of Shah Begum by Jahangir.[32]

Jahangir paid obeisance to his mother by touching her feet. He records these instances with a sense of pride. His reference to his mother was preceded by epithet 'Hazrat', one that is usually reserved for His Majesty himself.[33] These courtesies demonstrate the amount of respect and love he held for his mother, Mariam-uz-Zamani. A number of royal functions took place in the household of Mariam-uz-zamani like Jahangir's solar weighing,[34] Jahangir's marriage to daughter of Jagat Singh,[35] and Shehzada Parviz's wedding to daughter of Sultan Murad Mirza.[36]

Religion

Akbar developed Hindu inclinations and allowed his Hindu wife to perform the customary rites in the royal palace.[37][38] Thus, contrary to the usual practice of sultans, Akbar allowed her to remain a Hindu and to maintain a Hindu temple in the royal palace. He himself participated in the puja she performed.[39] She was a devotee of Lord Krishna. Her palace was decorated with paintings of Lord Krishna and frescoes. Though she remained a Hindu, as per her wish, she was buried near her husband's grave.

Family advancement and Power consolidation

Akbar's friendly relations with the Rajputs began after his marriage with Heer Kunwari. This was an important step which profoundly influenced his future policies.[40] The marriage, secured for him the support of her family, from among whom he drew his leading counsellors.[17]

On his marriage with Heer Kunwari, Akbar summoned Raja Man Singh I, nephew of Heer Kunwari and son of Raja Bhagwan Das of Amer, the heir to the throne of Raja Bharmal, and took him into the imperial service, by giving him an office in his court.[17] Raja Bhagwan Das was also enrolled amongst the nobility.[40] Later, they both rose ultimately to high offices.[41]

The Rajas of Amer especially benefitted from their close association with the Mughals, and acquired immense wealth and power. Of twenty-seven Rajputs in Abu'l-Fazl list of mansabdars, thirteen were of Amber clan, and some of them rose to positions as high as that of imperial princes. Raja Bhagwan Das, for instance, became commander of 5000, the highest position available at that time, and bore the proud title Amir-ul-Umara (Chief Noble). His son, Man Singh I, rose even higher to become commander of 7000.[42] This position was not enjoyed by any one except the imperial princes. This marriage was thus, beneficial to both Mughals and Kachwaha Rajputs of Amer.

Akbar also allowed one of his sons, Prince Daniyal, to be brought up by Raja Bharmal's wife in Amer, as a gesture of honour to the raja's family.[43]

Political influence and power

Mariam uz-zamani was reported to have been a highly astute business woman, who ran an active international trade in spices, silk, etc.,[44] and thus, amassed a private fortune which dwarfed the treasury of many a European king.[45] She was among the most prodigious women traders at the Mughal court.[46] No other noblewoman on record seems to have been as adventurous a trader as the Queen mother.[47]

Mariam Zamani owned ships that carried pilgrims to and from the Islamic holy city Mecca. In 1613, her ship, the Rahīmī was seized by Portuguese pirates along with the 600-700 passengers and the cargo. Rahīmī was the largest Indian ship sailing in the Red Sea and was known to the Europeans as the "great pilgrimage ship". When the Portuguese officially refused to return the ship and the passengers, the outcry at the Moghul court was quite unusually severe. The outrage was compounded by the fact that the owner and the patron of the ship was none other than the revered mother of the current emperor. Mariam-uz-Zamani's son, the Indian emperor Jahangir, ordered the seizure of the Portuguese town Daman. This episode is considered to be an example of the struggle for wealth that would later ensue and lead to colonization of the Indian sub-continent.[48]

"Mariam-uz-Zamani was granted the right to issue official documents (singularly called farman), usually the exclusive privilege of the emperor."

She was one of the only four members of the court (another was the emperor) and the only woman to have the rank of 12,000 cavalry,[50] and was known to receive a jewel from every nobleman "according to his estate" each year on the occasion of New Year's festival.[46] Like only a few other women at the Mughal court, Mariam-uz-Zamani was granted the right to issue official documents (singularly called farman), usually the exclusive privilege of the emperor. Issuing of such orders was confined to the highest ladies of the harem such as Hamida Banu Begum, Mariam-uz-Zamani, Nur Jehan, Mumtaz Mahal, Nadira Banu and Jahanara Begum.[46][51][52] Mariam Zamani, like Nur Jehan, used her wealth and influence to build gardens, wells, and mosques around the countryside.[46][53]

Death

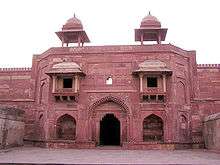

Mariam uz-Zamani died in 1623.[1] Even in her death, she remained closest to her husband. She is Akbar's only wife to be buried close to him, as per her wish.[54] A vav or step well was constructed by her son, Emperor Jahangir,as per her last wishes. The grave itself is underground with a flight of steps leading to it. Her tomb, built in 1623-27, is on the Tantpur road now known as in Jyoti Nagar. Though she remained Hindu after her marriage, she was buried according to Islamic custom, near her husband's mausoleum. Mariam's Tomb is only a kilometre from Tomb of Akbar the Great. The tomb's location reduced its chances of becoming a tourist attraction, but likewise, its lack of visibility meant it fell into a state of disrepair.[55] Later, taken over by ASI, her resting place is now dignified.[56]

There are some interesting aspects to the tomb, principally the ASI slab at the entrance which proclaims the tomb to be that of Mariam Uz Zamani, the princess of Amer who married Akbar and later gave birth to Jahangir.[57] Another interesting aspect of the tomb is that the building looks identical from the front and back and unlike other Mughal era structures, the back entrance is not a dummy.[58] The Mosque of Mariam Zamani Begum Sahiba was built by her son Nuruddin Salim Jahangir in her honour and is situated in the Walled City of Lahore, present day Pakistan. It is one of the earliest mosques in Lahore. The mosque also has a distinction of being one of the biggest mosques in present day Pakistan.

The misnomer of Jodhabai

There is a popular perception that the wife of Akbar, mother of Jahangir, was also known as "Jodha Bai".[59]

Her name as in Mughal chronicles was Mariam-uz-Zamani. Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, the autobiography of Jahangir, doesn't mention Jodha Bai nor Harka Bai or Heer Kunwari.[59] Therein, she is referred to as Mariam-uz-Zamani.[60] Neither the Akbarnama (a biography of Akbar commissioned by Akbar himself), nor any historical text from the period refer to her as Jodha Bai.[60]

According to Professor Shirin Moosvi, a historian of Aligarh Muslim University, the name "Jodha Bai" was first used to refer to Akbar's wife in the 18th and 19th centuries in historical writings.[60] According to the historian Imtiaz Ahmad, the director of the Khuda Baksh Oriental Public Library in Patna, it was Lieutenant-Colonel James Tod who first mentioned Jodhabai in his book Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan.[61]

"In the Akbarnama, there is a mention of Akbar marrying a Rajput princess of Amer but her name is not Jodhaa," says historian and director of the Khuda Baksh Oriental Public Library, Imtiaz Ahmad in Patna. She is referred to as Mariam Zamani (Mary of the Age). This is a title and not a name. It further says that Mariam Zamani is a title referred to the lady who gave birth to Prince Salim, who became Emperor Jehangir. But the name Jodha is not mentioned anywhere.[62]

Professor N R Farooqi, a historian of Allahabad Central University, states that Jodha Bai was not the name of Akbar's queen instead it was the name of Jahangir's wife Taj Bibi Bilqis Makani the Princess of Jodhpur, whose real name was Jagat Gosain.[59]

In popular culture

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mariam uz-Zamani. |

- Jodha Bai, a misnomer frequently used in reference to Mariam uz-Zamani, is a main character in the award-winning and legendary Indian film Mughal-e-Azam (1960), directed by K. Asif. Her character is played by Durga Khote.

- Jodha Bai is the lead character in the Indian epic film Jodhaa Akbar (2008), directed by Ashutosh Gowarikar. Aishwarya Rai played Jodha Bai.

- Mariam uz-Zamani is a character in Salman Rushdie's ninth novel The Enchantress of Florence (2008). She is also referred to in the book by her maiden name, Hira Kunwari.[63]

- Jodha Bai is the title character in the Ekta Kapoor's historical serial Jodha Akbar (2013). The character is portrayed by Paridhi Sharma.[64]

References

- 1 2 3 Christopher Buyers. "Timurid Dynasty GENEALOGY delhi4". Royalark.net. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ↑ Jahangirnama (1909). Alexander Rogers and Henry Beveridge, ed. The Tūzuk-i-Jahāngīrī, Volume 2. Royal Asiatic Society, London. p. 261.

- ↑ Jahangir (1909). Rogers and Beveridge, ed. The Tūzuk-i-Jahāngīrī, Volume 2. Royal Asiatic Society, London. p. 261.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne, The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. ISBN 0141001437.

- ↑ Lal, Ruby (2005). Domesticity and power in the early Mughal world. Cambridge University Press. p. 170. ISBN 9780521850223.

- ↑ Metcalf, Barbara, Thomas (2006). A Concise History of Modern India. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9.

- ↑ Christopher Buyers. "Timurid Dynasty GENEALOGY delhi5". Royalark.net. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ↑ Milford, Humphrey (1921). Early Travels In India By William Foster,. Oxford University Press. p. 203.

- ↑ Ahmed, Nazeer (2000). Islam in Global History: Volume Two. Xlibris Corporation. p. 51. ISBN 0-7388-5965-6.

- ↑ Giri, S.Satyanand (2009). Akbar. Trafford Publishing, Victoria, B.C., Canada. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-4269-1561-1.

- ↑ Smith, B.G. (2008). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History: 4 Volume Set. Oxford University Press. p. 656. ISBN 978-019-514890-9.

- ↑ Syed Firdaus Ashraf (2008-02-05). "Did Jodhabai really exist?". Rediff.com. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1917). Akbar the Great Mogul. Oxford, Clarendon Press. p. 58. ISBN 0895634716.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne, The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 136. ISBN 0141001437.

- ↑ Metcalf, Barbara, Thomas (2006). A Concise History of Modern India. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9.

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1917). Akbar the Great Mughal. Oxford, Clarendon Press. p. 58. ISBN 0895634716.

- 1 2 3 Garrett, Edwardes (1930). Mughal Rule in India. Oxford University Press,Great Britain. p. 30.

- ↑ "Part Sixteen:Fatehpur Sikri". Columbia.edu. Retrieved 2013-11-26.

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1919). Akbar the Great Mogul. Oxford, Clarendon Press. p. 102. ISBN 0895634716.

- ↑ Syed Firdaus Ashraf (2008-02-05). "Did Jodhabai really exist?". Rediff.com. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1917). Akbar the Great Mogul. Oxford, Clarendon Press. p. 58. ISBN 0895634716.

- ↑ Tirmizi, S.A.I. (1979). Edicts from the Mughal Harem. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli. pp. 12–13. OCLC 465427663.

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1917). Akbar the Great Mogul. Oxford, Clarendon Press. p. 58. ISBN 0895634716.

- ↑ Mukhia, Harbans (2004). The Mughals of India. Wiley, John & Sons, Incorporated. p. 133. ISBN 0631185550.

- ↑ Mehta, J.L. Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd, 1986. p. 222. ISBN 9788120710153.

- ↑ Edwardes, Stephen Meredyth. Mughal Rule in India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist, 1995. p. 30. ISBN 9788171565511.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne, The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 136. ISBN 0141001437.

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1917). Akbar the Great Mogul. Oxford, Clarendon Press. p. 58. ISBN 0895634716.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne, The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 145. ISBN 0141001437.

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1917). Akbar the Great Mogul. Oxford, Clarendon Press. p. 225. ISBN 0895634716.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne, The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 273. ISBN 0141001437.

- ↑ Jahangir (1968). Henry Beveridge, ed. The Tūzuk-i-Jahāngīrī: or, Memoirs of Jāhāngīr, Volume 1. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 56.

- ↑ Mukhia, Harbans (2008). The Mughals of India. Wiley India Pvt Ltd. p. 116. ISBN 9788126518777.

- ↑ Jahangir (1968). Henry Beveridge, ed. The Tūzuk-i-Jahāngīrī: or, Memoirs of Jāhāngīr, Volume 1. Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 78, 230.

- ↑ Jahangir (1968). Henry Beveridge, ed. The Tūzuk-i-Jahāngīrī: or, Memoirs of Jāhāngīr, Volume 1. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 145.

- ↑ Jahangir (1968). Henry Beveridge, ed. The Tūzuk-i-Jahāngīrī: or, Memoirs of Jāhāngīr, Volume 1. Munshiram Manoharlal. p. 81.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne, The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 136. ISBN 0141001437.

- ↑ Agrawal, Ashvini (1983). Studies in Mughal History. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 126. ISBN 9788120823266.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne, The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 136. ISBN 0141001437.

- 1 2 Garrett, Edwardes (1930). Mughal Rule in India. Oxford University Press,Great Britain. p. 40.

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1917). Akbar the Great Mogul. Oxford, Clarendon Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 0895634716.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne, The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 146. ISBN 0141001437.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne, The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. p. 193. ISBN 0141001437.

- ↑ Eraly, Abraham (2007). The Mughal World: Life in India's Last Golden Age. Penguin Books India. p. 133. ISBN 0143102621.

- ↑ Anuradha Verma (2011-05-06). "Akbar had no real love". The Times of India. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Findly, Ellison B. (1988). "The Capture of Maryam-uz-Zamānī's Ship: Mughal Women and European Traders". Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 108 (2): 232. doi:10.2307/603650. JSTOR 603650.

- ↑ Findly, Ellison B. (1988). "The Capture of Maryam-uz-Zamānī's Ship: Mughal Women and European Traders". Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 108 (2): 233. doi:10.2307/603650. JSTOR 603650.

- ↑ Findly, Ellison B. (1988). "The Capture of Maryam-uz-Zamānī's Ship: Mughal Women and European Traders". Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 108 (2): 227–238. doi:10.2307/603650. JSTOR 603650.

- ↑ Tirmizi, S.A.I. (1979). Edicts from the Mughal Harem. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli. pp. 127–128. OCLC 465427663.

- ↑ Prasad, Ram Chandra (1980). Early English Travellers in India: A Study in the Travel Literature of the Elizabethan and Jacobean Periods with Particular Reference to India. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 106. ISBN 9788120824652.

- ↑ Tirmizi, S.A.I. (1979). Edicts from the Mughal Harem. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli. pp. 127–128. OCLC 465427663.

- ↑ Mishra, Rekha. Women in Mughal India, 1526-1748 A.D. Munshiram Manoharlal, 1967. p. 67. ISBN 9788121503471.

- ↑ Mishra, Rekha. Women in Mughal India, 1526-1748 A.D. Munshiram Manoharlal, 1967. p. 112. ISBN 9788121503471.

- ↑ The Fatehpur Sikri Chronicles

- ↑ Arjun Kumar (2008-03-06). "Mariam Zamani's tomb: Jodha's rest". The Economic Times, TNN. Retrieved 2013-12-06.

- ↑ Arjun Kumar (2008-03-06). "Mariam Zamani's tomb: Jodha's rest". The Economic Times, TNN. Retrieved 2013-12-06.

- ↑ Arjun Kumar (2008-03-06). "Mariam Zamani's tomb: Jodha's rest". The Economic Times, TNN. Retrieved 2013-12-06.

- ↑ Arjun Kumar (2008-03-06). "Mariam Zamani's tomb: Jodha's rest". The Economic Times, TNN. Retrieved 2013-12-06.

- 1 2 3 Atul Sethi (2007-06-24). "'Trade, not invasion brought Islam to India'". The Times of India. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- 1 2 3 Ashley D'Mello (2005-12-10). "Fact, myth blend in re-look at Akbar-Jodha Bai". The Times of India. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ↑ Syed Firdaus Ashraf (2008-02-05). "Did Jodhabai really exist?". Rediff.com. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ↑ Syed Firdaus Ashraf (2008-02-05). "Did Jodhabai really exist?". Rediff.com. Retrieved 2008-02-15.

- ↑ Ursula K Le Guin (2008-03-29). "The real uses of enchantement". The Guardian. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ↑ Chaya Unnikrishnan (2013-06-26). "So far, so good". dnaindia.com. Retrieved 2013-12-04.