Maria Sibylla Merian

| Maria Sibylla Merian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

2 April 1647 Frankfurt, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died |

13 January 1717 (aged 69) Amsterdam, Dutch Republic |

| Occupation | Naturalist, scientific illustrator, entomologist |

| Known for | Documentation of butterfly metamorphosis, scientific illustration |

Maria Sibylla Merian (2 April 1647 – 13 January 1717) was a German-born naturalist and scientific illustrator, a descendant of the Frankfurt branch of the Swiss Merian family, founders of one of Europe's largest publishing houses in the 17th century.

Merian received her artistic training from her stepfather, Jacob Marrel, a student of the still life painter Georg Flegel. She remained in Frankfurt until 1670, relocating subsequently to Nuremberg, Wieuwerd (1685), where she stayed in a Labadist community till 1691, and Amsterdam.

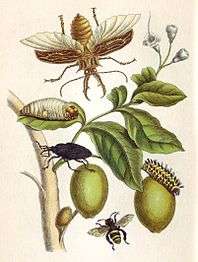

Merian published her first book of natural illustrations, titled Neues Blumenbuch, in 1675 at age 28.[1] In 1699, following eight years of painting and studying, and on the encouragement of Cornelis van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck, the then-governor of the Dutch colony of Surinam, the city of Amsterdam awarded Merian a grant to travel to South America with her daughter Dorothea.[2] Her trip, designed as a scientific expedition makes Merian perhaps the first person to "plan a journey rooted solely in science."[3] After two years there, malaria forced her to return to Europe.[1][2] She then proceeded to publish her major work, Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, in 1705, for which she became famous. Because of her careful observations and documentation of the metamorphosis of the butterfly, she is considered by David Attenborough[4] to be among the most significant contributors to the field of entomology. She was a leading entomologist of her time and she discovered many new facts about insect life through her studies.[5]

Early life and early career

Maria Sibylla Merian was born on 2 April 1647 in Frankfurt, then a free imperial city of the Holy Roman Empire, into the family of the Swiss engraver and publisher Matthäus Merian the Elder. Early on, she had access to many books about natural history.[6] Her father died three years later, and in 1651 her mother married still life painter Jacob Marrel. Marrel encouraged Merian to draw and paint. While he lived mostly in Holland his pupil Abraham Mignon trained her. At the age of thirteen she painted her first images of insects and plants from specimens she had captured.[7] Regarding her youth, in the foreword to Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, Merian wrote: "I spent my time investigating insects. At the beginning, I started with silk worms in my home town of Frankfurt. I realized that other caterpillars produced beautiful butterflies or moths, and that silkworms did the same. This led me to collect all the caterpillars I could find in order to see how they changed".[8]

In 1665 Merian married Marrel's apprentice, Johann Andreas Graff from Nuremberg; his father was a poet and director of the local high school, one of the leading schools in 17th century Germany. Two years later she had her first child, Johanna Helena, and the family moved to Nuremberg, her husband's home town. While living there, Merian continued painting, working on parchment and linen, and creating designs for embroidery. She also gave drawing lessons to unmarried daughters of wealthy families (her "Jungferncompaney", i.e. virgin group), which helped her family financially and increased its social standing. This provided her with access to the finest gardens, maintained by the wealthy and elite where she could continue collecting and documenting insects.[6] In 1678, she gave birth to her second daughter.[9]

In 1679, she published her first work on insects which was a two-volume, illustrated book focusing on insect metamorphosis.[7]

In 1681 she moved to Frankfurt am Main to live with her mother, after her stepfather died. In 1685 the family moved to Friesland where her half-brother Caspar Merian lived in a religious community. She split with her husband as well.[7]

Friesland

Jean de Labadie set up a his community in a stately home – Walta Castle – at Wieuwerd in Friesland, which belonged to three sisters Van Aerssen van Sommelsdijck, who were his adherents. Here printing and many other occupations continued, including farming and milling.

At its peak, the community numbered around 600 with many more adherents further afield. Visitors came from England, Italy, Poland and elsewhere, but not all approved of the strict discipline. Those of arrogant disposition were given the most menial of jobs. Fussiness in matters or food was overcome since all were expected to eat what was put in front of them.

Several noted visitors have left their accounts of visits to the Labadist community. One was Sophie of Hanover, mother of King George I of Great Britain; another was William Penn, the Quaker pioneer, who gave his name to the US state of Pennsylvania; a third was the English philosopher John Locke.[10]

In 1690 her mother died.

Amsterdam

In 1691 she moved with her daughters to Amsterdam and met with Caspar Commelin and Steven Blankaart. In 1692 she divorced from her husband.

In 1699 the city of Amsterdam granted Merian permission to travel to Suriname in South America, along with her younger daughter Dorothea Maria. The goal of the mission was to spend five years illustrating new species of insects.[7] In order to finance the mission, she sold 255 of her own paintings.[3] Before departing, she wrote:

In Holland, with much astonishment what beautiful animals came from the East and West Indies. I was blessed with having been able to look at both the expensive collection of Doctor Nicolaas Witsen, mayor of Amsterdam and director of the East Indies society, and that of Mr. Jonas Witsen, secretary of Amsterdam. Moreover I also saw the collections of Mr. Fredericus Ruysch, doctor of medicine and professor of anatomy and botany, Mr. Livinus Vincent, and many other people. In these collections I had found innumerable other insects, but finally if here their origin and their reproduction is unknown, it begs the question[sic] as to how they transform, starting from caterpillars and chrysalises and so on. All this has, at the same time, led me to undertake a long dreamed of journey to Suriname.[8]

Suriname

Merian worked in Suriname, which included what later became known as the French, Dutch and British Guianas, for two years,[13] traveling around the colony and sketching local animals and plants. She criticized Dutch planters' treatment of natives and black slaves. She recorded local native names for the plants and described local uses. In 1701 malaria possibly forced her to return to the Dutch Republic.[7]

_1987%2C_MiNr_788.jpg)

Back in the Netherlands, Merian sold specimens she had collected and published a collection of engravings of plant and animal life in Suriname. In 1705 she published a book Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium about the insects of Suriname.[5]

In 1715, Merian suffered a stroke and was partially paralysed. She continued her work, but her illness probably affected her ability to work. A later registry lists her as a pauper.

Maria Sibylla Merian died in Amsterdam on 13 January 1717 and was buried four days later. Her daughter Dorothea published Erucarum Ortus Alimentum et Paradoxa Metamorphosis, a collection of her mother's work, posthumously.

Modern Appreciation

In the last quarter of the 20th century, the work of Merian was re-evaluated, validated, and reprinted.[14] Her portrait was printed on the 500 DM note before Germany converted to the euro. Her portrait has also appeared on a 0.40 DM stamp, released on 17 September 1987, and many schools are named after her. In 2005, a modern research vessel named Maria S. Merian was launched at Warnemünde, Germany. She was honored with a Google Doodle on 2 April 2013 to mark her 366th birth anniversary.[15]

Work

Merian worked as a botanical artist. She published collections of engravings of plants in 1675, 1677, and 1680. She collected and observed live insects and created detailed drawings to illustrate insect metamorphosis. In her time, it was very unusual that someone would be genuinely interested in insects, which had a bad reputation and were considered "vile and disgusting."[7] As a consequence of their reputation, the metamorphosis of these animals was largely unknown. Merian described the life cycles of 186 insect species, amassing evidence that contradicted the contemporary notion that insects were "born of mud" by spontaneous generation.Moreover, although certain scholars were aware of the process of metamorphosis from the caterpillar to the butterfly, the majority of people did not understand the process.

Merian's process of creating her art used vellum charta non nata which she primed with a white coat.[16] Because of the guild system in Europe, women were not allowed to paint in oil.[3] Merian painted with watercolors and gouache, instead.[16]

The work that Anna Maria Sibylla Merian published, Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung – The Caterpillars' Marvelous Transformation and Strange Floral Food, was very popular in certain segments of high society as a result of being published in the vernacular. However, her work was largely ignored by scientists of the time because the official language of science was still Latin.

Merian also described many other details of the evolution and life cycle of the insects she observed. For example, she showed that each stage of the change from caterpillar to butterfly depended on a small number of plants for its nourishment. She noted that as a consequence the eggs were laid near these plants.[6]

Merian was one of the first naturalists to observe insects directly.[7] This approach gave her much more insight into their lives and was contrary to the way that most scientists worked at the time.

The pursuit of her work in Suriname was an unusual endeavour, especially for a woman. In general, only men received royal or government funding to travel in the colonies to find new species of plants and animals, make collections and to work there, or to settle. Scientific expeditions at this period of time were not common, and Merian's unofficial, self-funded expedition raised many eyebrows. She succeeded, however, in discovering a whole range of previously unknown animals and plants in the interior of Surinam. Merian spent time studying and classifying her findings and described them in great detail. She not only described the insects she found, but also noted their habitat, habits and uses to indigenous people.[6] Her classification of butterflies and moths is still relevant today. She used Native American names to refer to the plants, which became used in Europe:

I created the first classification for all the insects which had chrysalises, the daytime butterflies and the nighttime moths. The second classification is that of the maggots, worms, flies, and bees. I retained the indigenous names of the plants, because they were still in use in America by both the locals and the Indians.[8]

Merian's drawings of plants, frogs,[17] snakes, spiders, iguanas, and tropical beetles are still collected today by amateurs all over the world. The German word Vogelspinne—(a spider of the infraorder Mygalomorphae), translated literally as bird spider—probably has its origins in an engraving by Maria Sibylla Merian. The engraving, created from sketches drawn in Surinam, shows a large spider who had just captured a bird. In the same engraving and accompanying text Merian was the first European to describe both army ants and leaf cutter ants as well as their effect on other organisms.[18]

Shortly before Merian's death, her work was seen in Amsterdam by Peter the Great. After her death he acquired a significant number of her paintings[19] which to this day are kept in academic collections in St. Petersburg.[20]

Popular culture

On 2 April 2013, Merian was honoured with a Google Doodle, in celebration of her 366th birthday.[21]

Gallery

See also

Bibliography

| Library resources about Maria Sibylla Merian |

| By Maria Sibylla Merian |

|---|

- Neues Blumenbuch. Volume 1. 1675

- Neues Blumenbuch. Volume 2. 1677

- Neues Blumenbuch. Volume 3. 1677

- Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung und sonderbare Blumennahrung. 1679

- Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium. 1705

Footnotes

- 1 2 Cavna, Michael (April 2, 2013). "Maria Sibylla Merian Doodle: Naturally, Google celebrates the artist's evergreen legacy". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- 1 2 GrrlScientist (April 2, 2013). "Maria Sibylla Merian: artist whose passion for insects changed science". The Guardian (London). Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Reidell, Heidi (April 2008). "A Study of Metamorphosis". Americas 60 (2): 28–35. Retrieved 10 August 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Natural Curiosities film, BBC

- 1 2 Kristensen, Niels P. (1999). "Historical Introduction". In Kristensen, Niels P. Lepidoptera, moths and butterflies: Evolution, Systematics and Biogeography. Volume 4, Part 35 of Handbuch der Zoologie:Eine Naturgeschichte der Stämme des Tierreiches. Arthropoda: Insecta. Walter de Gruyter. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-11-015704-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Todd, Kim (June 2011). "Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717): An Early Investigator of Parasitoids and Phenotypic Plasticity". Terrestrial Arthropod Reviews 4 (2): 131–144. doi:10.1163/187498311X567794. Retrieved 10 August 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Swaby, Rachel (2015). Headstrong: 52 Women Who Changed Science - And the World. New York: Broadway Books. pp. 47–50. ISBN 9780553446791.

- 1 2 3 Foreword from Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (Metamorphosis of the Insects of Surinam)

- ↑ Wulf, Andrea (January 2016). "The Woman Who Made Science Beautiful". The Atlantic. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ Glausser, Wayne (1998). Locke and Blake: a conversation across the eighteenth century. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 23–4. ISBN 0-8130-1570-7.

- ↑ "Digitaler Portraitindex: Bildnis Esther Barbara von Sandrart, geb. Bloemart".

- ↑ Adrian Staecker. "Virtuelles Kupferstichkabinett".

- ↑ de Bray (2001), p. 48.

- ↑ Erlanger-Glozer, Liselotte (March–April 1978). "Maria Sibylla Merian, 17th Century Entomologist, Artist, and Traveller". Insect World Digest 3 (2): 12–21.

- ↑ Lachno, James. "Maria Sibylla Merian: Scientific illustrator honoured with Google doodle". The Daily Telegraph (London). Retrieved April 2, 2013.

- 1 2 Kopaneva, N.P. (February 2010). "The Vivid Colors of Merian". Science First Hand 25 (1): 110–123. Retrieved 10 August 2015. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Etheridge, Kay (2010). "Maria Sybilla Merian's Frogs" (PDF). Bibliotheca Herpetologica 8: 20–27.

- ↑ Etheridge, Kay (2011). "Maria Sibylla Merian and the metamorphosis of natural history" (PDF). Endeavour 35 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1016/j.endeavour.2010.10.002. PMID 21126767.

- ↑ Todd (2007), pp. 228–229

- ↑ Wettengl, Kurt, ed. (1998). Maria Sibylla Merian, 1647–1717: artist and naturalist. Ostfildern-Ruit: Verlag Gerd Hatje. pp. 34 and 54. ISBN 3775707514.

- ↑ Lachno, James (April 2, 2013). "Maria Sibylla Merian: Scientific illustrator honoured with Google doodle". London: The Telegraph. Retrieved April 2, 2013.

References

- de Bray, Lys (2001). The Art of Botanical Illustration: A history of classic illustrators and their achievements. Quantum Publishing Ltd., London. ISBN 1-86160-425-4.

- Patricia Kleps-Hok: Search for Sibylla: The 17th Century's Woman of Today, U.S.A 2007, ISBN 1-4257-4311-0; ISBN 1-4257-4312-9.

- Helmut Kaiser: Maria Sibylla Merian: Eine Biografie. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2001, ISBN 3-538-07051-2

- Uta Keppler: Die Falterfrau: Maria Sibylla Merian. Biographischer Roman. dtv, München 1999, ISBN 3-423-20256-4 (Nachdruck der Ausgabe Salzer 1977)

- Charlotte Kerner: Seidenraupe, Dschungelblüte: Die Lebensgeschichte der Maria Sibylla Merian. 2. Auflage. Beltz & Gelberg, Weinheim 1998, ISBN 3-407-78778-2

- Dieter Kühn: Frau Merian! Eine Lebensgeschichte. S. Fischer, Frankfurt 2002, ISBN 3-10-041507-8

- Inez van Dullemen: Die Blumenkönigin: Ein Maria Sybilla Merian Roman. Aufbau Taschenbuch Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-7466-1913-0

- Kurt Wettengl: Von der Naturgeschichte zur Naturwissenschaft – Maria Sibylla Merian und die Frankfurter Naturalienkabinette des 18. Jahrhunderts. Kleine Senckenberg-Reihe 46: 79 S., Frankfurt am Main 2003

- Kim Todd: Chrysalis: Maria Sibylla Merian and the Secrets of Metamorphosis. Harcourt, USA, 2007. ISBN 0-15-101108-7.

- Ella Reitsma: "Maria Sibylla Merian & Daughters, Women of Art and Science" Waanders, 2008. ISBN 978-90-400-8459-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maria Sibylla Merian. |

- Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium:

- Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium images at website sponsored by Johns Hopkins University

- Online version of Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium from GDZ

- Das kleine Buch der Tropenwunder : kolorierte Stiche from the Digital Library of the Caribbean

- Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (1705) - full digital facsimile from the Linda Hall Library

- Online version of Over de voortteeling en wonderbaerlyke veranderingen der Surinaemsche Insecten from GDZ

- Online version of Erucarum ortus, alimentum et paradoxa metamorphosis from GDZ

- Online version of De Europische Insecten

- The Flowering Genius of Maria Sibylla Merian Ingrid Rowland on Merian from The New York Review of Books

- Der Raupen wunderbare Verwandlung, images from collection at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Gaedike, R.; Groll, E. K. & Taeger, A. 2012: Bibliography of the entomological literature from the beginning until 1863 : online database – version 1.0 – Senckenberg Deutsches Entomologisches Institut.

-

"Merian, Marie Sibylle". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

"Merian, Marie Sibylle". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

|

_by_Maria_Sibylla_Merian.jpg)