Maria Clara Eimmart

Maria Clara Eimmart (1676–1707), was a German astronomer, engraver and designer. She was the daughter and assistant of Georg Christoph Eimmart, the younger.[1]

Biography

Maria Clara Eimmart was a German Astronomer born in 1676.[1] She was the daughter of painter, engraver, and amateur astronomer Georg Christoph Eimmart, the younger.[2] Her father's profession was a lucrative one, but he spent all of his earnings in the purchase of astronomical instruments. He was a diligent observer and published his results in various memoirs and transactions of society. Her grandfather, Georg Christoph Eimmart the elder, was also an engraver and painter.[3] Eimmart the elder painted portraits, still-life, landscapes, and historical subjects. In 1678,[1] Maria Clara Eimmart’s father built a private observatory in Nuremberg on the city wall.[4] From 1699 to 1704,[4] Georg Christoph Eimmart was the director of the Nuremberg Academy of Art, the Malerakademie.[5] Through her father, Maria Clara Eimmart received an education in French, Latin, Mathematics and drawing. Through her broad education in the fine arts, she specialized in botanical and astronomical illustrations. Because of the strength of the crafts tradition in Germany, Eimmart was able to take advantage of the opportunity to train as an apprentice to her father and learned the art of astronomy from him.[4]

Eimmart's skills as an engraver allowed her to assist her father in his work.[2] Eimmart's skill in creating exact sketches led to her success in both astronomical and botanical illustration. In addition to Eimmart's depictions of the sun and moon, she also illustrated flowers, birds, ancient statues, and ancient women, but most of Maria Clara's paintings of nature and art have been lost.[1]

In 1706, Eimmart married Johann Heinrich Muller, her father’s pupil and successor.[5] Muller taught physics at the Nuremberg Gymnasium, where Eimmart assisted her husband. Their marriage successfully secured Eimmart’s position at the observatory. Muller was so influenced by the family love for astronomy that he became a diligent amateur and afterwards a professor at Altorf, where he used his manual skill in depicting comets, sun-spots, and lunar mountains aided by his talented wife. With these in their earlier Nuremberg home were associated the two Rost Brothers, novelists and astronomers; also Wurtzelbauer, and Doppelmayer, a historian of astronomy. Muller became the director of the Eimmart observatory in 1705. Muller also benefited from the marriage, because of the principle of daughter’s rights, the Eimmart's observatory was part of Maria’s inheritance, which then passed from daughter to husband. Maria Clara Eimmart died in childbirth in 1707.[1]

Astronomical Illustrations

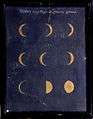

Eimmart is best known for her exact astronomical illustrations. Between 1693 and 1698, Eimmart made over 350 drawings of the phases of the moon.[1] This collection of drawings, drawn solely form observations through a telescope was called Micrographia stellarum phases lunae ultra 300 and was depicted on a distinctive blue paper. Twelve of these were given to conte Marsili, a scientific collaborator of her father, and ten survive in Bologna, together with three smaller studies on brown paper.[5] Eimmart’s continuous series of depictions became the base for a new lunar map.[1]

In 1706, Eimmart also illustrated two depictions of the total eclipse. Schiebinger states that some sources claim Eimmart published a work under her father’s name in 1701, the Ichnographia nova contemplationum de sole. However, there is no evidence to support that this was her work and not her father’s.[1]

Gallery

-

Phase of the Moon observed

-

Second Phase of the Moon

-

Illustration of the full Moon

-

Phase of Mercury Observed by Johannes Hevelius

-

Phase of Venus

-

Aspect of Mars

-

Aspect of Jupiter

-

Aspect of Saturn

-

Comets

-

Paraselene and Parhelion

-

Astronomical illustrations

See also

Astronomical Illustrations by Maria Clara Eimmart

Maria Clara Eimmart at Astronomie in Nürnberg

Georg Christoph Eimmart at Astronomie in Nürnberg

Drawing of a Vestalin by Maria Clara Eimmart Germanischen Nationalmuseum Nürnberg

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Schiebinger, Londa (1991). The mind has no sex? : women in the origins of modern science (1st Harvard pbk. ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674576254.

- 1 2 eds, William W. Payne; H.C. Wilson (1898). "Maria Clara Muller". Popular Astronomy Vol. 6. Minnesota: Goodsell Observatory of Charleton College.

- ↑ Bryan, Michael (1886). Dictionary of Painters and Engravers: biographical and critical. London: George Bell and Sons.

- 1 2 3 eds, Marilyn Ogilvie; Joy Harvey (2000). The biographical dictionary of women in science. New York [u.a.]: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92038-4.

- 1 2 3 Jeffares, Neil. "Maria Clara Eimmart". Dictionary of pastellists before 1800. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

Literature

- Hans Gaab: Zum 300. Todestag von Maria Clara Eimmart (1676–1707). In: Regiomontanusbote. 20, 4/2007, S. 7–19.

- Hans Gaab: Maria Clara Eimmart. Eine Nürnberger Astronomin. In: Nadja Bennewitz, Gaby Franger: Geschichte der Frauen in Mittelfranken. Alltag, Personen und Orte. Ars vivendi, Cadolzburg 2003, S. 145–152.

- Ronald Stoyan: Die Nürnberger Mondkarten. Teil 1: Die Mondkarte von Georg Christoph Eimmart (1638–1705) und Maria Clara Eimmart (1676–1707). In: Regiomontanusbote. 14, 1/2001, S. 29–39.

- Karl Christian Bruhns (1877), "Eimmart, Georg Christoph", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German) 5, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, p. 758

- Siegmund Günther (1885), "Müller, Johann Heinrich", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German) 22, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 583–585

- Adolf Wißner (1959), "Georg Christoph Eimmart", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German) (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot) 4: 394–394, (full text online)

|