Marcellus Empiricus

Marcellus Empiricus, also known as Marcellus Burdigalensis (“Marcellus of Bordeaux”), was a Latin medical writer from Gaul at the turn of the 4th and 5th centuries. His only extant work is the De medicamentis, a compendium of pharmacological preparations drawing on the work of multiple medical and scientific writers as well as on folk remedies and magic. It is a significant if quirky text in the history of European medical writing, an infrequent subject of monographs, but regularly mined as a source for magic charms, Celtic herbology and lore, and the linguistic study of Gaulish and Vulgar Latin.[1] Bonus auctor est (“he’s a good authority”) was the judgment of J.J. Scaliger,[2] while the science historian George Sarton called the De medicamentis an “extraordinary mixture of traditional knowledge, popular (Celtic) medicine, and rank superstition.”[3] Marcellus is usually identified with the magister officiorum of that name who held office during the reign of Theodosius I.

Life and political career

Little is known of the life of Marcellus. The primary sources are:

- Marcellus’s own preface to the De medicamentis;

- the Codex Theodosianus (probably referring to this Marcellus);

- a letter written in 399 by Symmachus to a Marcellus who is likely to have been the medical writer;

- a letter written by the Antiochan scholar Libanius that mentions a Marcellus;

- an inscription in Narbonne (his association with which would require that he not be from Bordeaux; see below);

- an anecdote in Orosius about an unnamed Gaul (also a highly conjectural link).

The Gallic origin of Marcellus is rarely disputed, and he is traditionally identified with the toponym Burdigalensis; that is, from Bordeaux (Latin Burdigala), within the Roman province of Aquitania. In his prefatory epistle, he refers to three Bordelaise praetorian prefects as his countrymen: Siburius, Eutropius, and Julius Ausonius, the father of the poet Decimus Magnus Ausonius.[4] He is sometimes thought to have come from Narbonne rather than Bordeaux.[5] There has been an attempt to make a Spanish senator of him on the basis of Symmachus’s reference to property he owned in Spain; but this inference ignores that Marcellus is said explicitly to have left Spain to return to living in avitis penatibus, or among the household spirits of his grandfathers — that is, at home as distinguished from Spain. He probably wrote the De medicamentis liber during his retirement there.[6]

The author of the De medicamentis is most likely the Marcellus who was appointed magister officiorum by Theodosius I. The heading of the prefatory epistle identifies him as a vir inlustris, translatable as “a distinguished man,” but a more formal designation of rank that indicates he had held imperial office. Marcellus’s 16th-century editor Janus Cornarius gives the unhelpful phrase ex magno officio (something like “from high office”); coupled with two references in the Theodosian Code to a Marcellus as magister officiorum,[7] Cornarius’s phrase has been taken as a mistaken expansion of the standard abbreviation mag. off. The magister officiorum was a sort of Minister of the Interior[8] and the identification is consistent with what is known of the author’s life and with the politics of the time.[9] His stated connection to the Ausonii makes it likely that he was among the several aristocratic Gauls who benefitted politically when the emperor Gratian appointed his Bordelaise tutor Ausonius to high office and from Theodosius’s extended residence in the western empire during the latter years of his reign.[10]

Marcellus would have entered his office sometime after April 394 A.D., when his predecessor is last attested,[11] and before the emperor’s death on January 17, 395. He was replaced in late November or December of 395, as determined by the last reference to a Marcellus holding office that is dated November 24 and by the dating of a successor.[12] The timing of his departure suggests that he had been a supporter of Rufinus, the calculating politician of Gallic origin who was assassinated November 27 of that year, having failed to resist if not facilitating the advance of Alaric and the Visigoths. Marcellus’s support may have been pragmatic or superficial; a source that condemns Rufinus heartily praises Marcellus as “the very soul of excellence.”[13]

Given Rufinus’s dealings with the Visigoths, however, it is conceivable that Marcellus should be identified with “a certain former high-ranking official from Narbonne” mentioned by Orosius[14] as present in Bethlehem in 415 A.D. While visiting Jerome, Orosius says he heard this Gaul relate the declaration made by Athaulf, king of the Visigoths, at Narbonne regarding his intentions toward the Roman empire.[15] John Matthews argued that Marcellus, who would have been about 60 at the time, is “clearly the most eligible candidate.”[16] Since Orosius identifies the Gaul only as having served under Theodosius, and as a “devout, cautious, and serious” person, other figures have been put forth as the likely bearer of the Athaulf declaration.[17]

Medical background

It is not unreasonable but also not necessary to conclude that Marcellus was a practicing physician. In his dissertation, the intellectual historian of magic and medicine Lynn Thorndike pronounced him the “court physician” of Theodosius I,[18] but the evidence is thin: Libanius, if referring to this Marcellus, praises his ability to cure a headache.[19] The prevailing view is that Marcellus should be categorized as a medical writer and not a physician.[20] A translator of the medical writings of Isidore of Seville characterizes Marcellus as a “medical amateur” and dismisses the De medicamentis as “nothing more than the usual ancient home remedies,”[21] and the historian of botany Ernst Meyer seems to have considered him a dilettante.[22]

Like Ausonius and later Sidonius Apollinaris, Marcellus is among those aristocratic Gauls of the 4th and 5th centuries who were nominally or even devoutly Christian but who fashioned themselves after the Republican ideal of the Roman noble: a career in politics balanced with country villas and informational or literary writing on a range of subjects, including philosophy, astronomy, agriculture, and the natural sciences.[23] Although medical writing might have been regarded as a lesser achievement, it was a resource for the pater familias who traditionally took personal responsibility for the health care of his household, both family members and slaves.[24]

Prescriptions for veterinary treatments dispersed throughout the De medicamentis also suggest the interests and concerns of the author — the letter from Symmachus serves mainly to inquire whether Marcellus can provide thoroughbred horses for games to be sponsored by his son, who has been elected praetor — and of his intended audience, either the owners of estates or the literate workers who managed them.[25] “Do-it-yourself” manuals were popular among the landowning elite because they offered, as Marcellus promises, a form of self-sufficiency and mastery.[26]

Alf Önnerfors has argued that a personal element distinguishes the De medicamentis from similar medical manuals, which are in effect if not fact anonymous. In the letter to his sons, whom he addresses as dulcissimi (“my sweetest”), Marcellus expresses the hope that they and their families will, in case of sickness, find support and remedies in their father’s manual, without intervention by doctors (sine medicis intercessione). This emphasis on self-reliance, however, is not meant to exclude others, but to empower oneself to help others; appealing to divina misericordia (“godlike compassion”), Marcellus urges his sons to extend caritas (“caring” or perhaps Christian “charity”) to strangers and the poor as well as to their loved ones.[27] The tone, Önnerfors concludes, is “humane and full of gentle humor.”[28]

Religious background

Marcellus is usually regarded as a Christian,[29] but he also embraces magico-medical practices that draw on the traditional religions of antiquity. Historian of botanical pharmacology Jerry Stannard believed that evidence in the De medicamentis could neither prove nor disprove Marcellus’s religious identity, noting that the few references to Christianity are “commonplace” and that, conversely, charms with references to Hellenistic magic occur widely in medieval Christian texts.[30] In his classic study The Cult of the Saints, Peter Brown describes and sets out to explain what he sees as “the exclusively pagan tone of a book whose author was possibly a Christian writing for a largely Christianized upper class.”[31] Historians of ancient medicine Carmélia Opsomer and Robert Halleux note that in his preface, Marcellus infuses Christian concerns into the ancient tradition of “doctoring without doctors.”[32] That Marcellus was at least a nominal Christian is suggested by his appointment to high office by Theodosius I, who exerted his will to Christianize the empire by ordering the Roman senate to convert en masse.[33]

The internal evidence of religion in the text is meager. The phrase divina misericordia in the preface appears also in St. Augustine’s De civitate Dei, where the reference to divine mercy follows immediately after a passage on barbarian incursions.[34] Marcellus and Augustine are contemporaries, and the use of the phrase is less a question of influence than of the currency of a shared Christian concept.[35] Elsewhere, passages sometimes cited as evidence of Christianity[36] on closer inspection only display the syncretism of the Hellenistic magico-religious tradition, as Stannard noted. Christ, for instance, is invoked in an herb-gathering incantation,[37] but the ritual makes use of magico-medical practices of pre-Christian antiquity. A Judaeo-Christian reference — nomine domini Iacob, in nomine domini Sabaoth[38] — appears as part of a magic charm that the practitioner is instructed to inscribe on a lamella, or metal leaf. Such “magic words” often include nonsense syllables and more-or-less corrupt phrases from “exotic” languages such as Celtic, Aramaic, Coptic, and Hebrew, and are not indications of formal adherence to a religion.[39]

The first reference to any religious figure in the text is Asclepius, the premier god of healing among the Greeks. Marcellus alludes to a Roman version of the myth in which Asclepius restores the dismembered Virbius to wholeness; as a writer, Marcellus says, he follows a similar course of gathering the disiecta … membra ("scattered body parts") of his sources into one corpus (whole body).[40] In addition to gods from the Greco-Roman pantheon, one charm deciphered as a Gaulish passage has been translated to invoke the Celtic god Aisus, or Esus as it is more commonly spelled, for his aid in dispelling throat trouble.[41]

Christian benefactor?

An inscription[42] dated 445 recognizes a Marcellus as the most important financial supporter in the rebuilding of the cathedral at Narbonne, carried out during the bishopric of St. Rusticus. John Matthews has argued that this Marcellus is likely to have been a son or near descendant of the medical writer, since the family of an inlustris is most likely to have possessed the wealth for such a generous contribution.[43] The donor had served for two years as praetorian prefect of Gaul. Assuming that the man would have been a native, Matthews weighs this piece of evidence with the Athaulf anecdote from Orosius to situate the author of the De medicamentis in the Narbonensis,[44] but this is a minority view.

The Book of Medicaments

Marcellus begins the De medicamentis liber by acknowledging his models. The texts he draws on include the so-called Medicina Plinii or “Medical Pliny,” the herbal (Herbarius) of Pseudo-Apuleius, and the pharmacological treatise of Scribonius Largus, as well as the most famous Latin encyclopedia from antiquity, the Historia naturalis of Pliny the Elder.[45]

The work is structured as follows:

- Epistolary dedication, addressed to Marcellus’s sons, a prose preface equivalent to seven paragraphs.

- Index medicalium scriptorum, or table of contents for the medical topics, listing the 36 chapter headings.

- A short tract on metrology,[46] with notes in Latin on units of measure and a conversion chart in Greek.

- Epistulae diversorum de qualitate et observatione medicinae (“Letters by various authors on ‘quality’ and ‘observation’ in medicine”), a series of seven epistles, each attributed to a different medical writer. The epistles serve as a literary device for discussing methodology, diagnosis, and the importance of ethical and accurate treatment.[47] They are not, or not wholly, fictional; just as Marcellus’s work begins with a prefatory epistle addressed to his sons, the seven letters represent prefaces to other authors’ works, some now lost. Marcellus has detached them from the works they headed and presented them collectively, translating, sometimes taking liberties, those originally in Greek, as a kind of bonus for his sons.[48] For instance, the “Letter from Celsus”, addressed to a Callistus, deals with the physician’s ethical duty in relation to the Hippocratic Oath.[49]

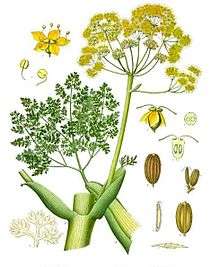

- Thirty-six chapters on treatments, consisting mainly of recipes both pharmacological and magical, and arranged by convention anatomically a capite ad calcem (“from head to toe,” in the equivalent English expression) as were Marcellus’s sources Scribonius Largus and the Medicina Plinii.[50] The treatment chapters run to 255 pages in Niedermann’s edition. Meyer lists 262 different plant names in Marcellus; allowing for synonyms, of which there are many, the number of plants mentioned would be around 131.[51] About 25 of the botanicals most frequently prescribed are “exotica”’ such as galbanum, sagapenum, and zingiber; these may have been available in Gaul as imports, but only to elite consumers. Other ingredients likely to have been rare for Marcellus’s intended audience include cinnamon, cloves, candied tragacanth, Alexandrian niter, and African snails, perhaps the Giant African land snail, which are prescribed live for pulping into a mélange. Availability is possibly a lesser criterion of selection for Marcellus than completeness and variety of interest.[52]

- And last, the Carmen de speciebus (“Song of Species”), a 78-line Latin hexameter poem on pharmacology, which Marcellus contrasts to his prose assemblage of prescriptions by asserting his originality in writing it.[53]

Significance as medical writer

Marcellus was a transitional figure between ancient and medieval materia medica. Although the contents of the recipes — their names, uses, and methods of treatment — derive from the medical texts of ancient Greece and Rome, the book also points forward to doctrines and approaches characteristic of medieval medicine. Marcellus is seldom cited directly, but his influence, though perhaps not wide or pervasive, can be traced in several medieval medical texts.[54]

A major change in the approach to writing about botanical pharmacology is signalled in the De Medicamentis. As texts associated with Mediterranean medicine traveled west and north with the expanding borders of the Roman empire, the plants required by drug recipes were no longer familiar, and the descriptions or illustrations provided by earlier herbals failed to correspond to indigenous flora. Marcellus’s practice of offering synonyms is one attempt to bridge this gap. He often provides a string of correspondences: the Greek plant name polygonos is first glossed as sanguinaria in Latin (1.2),[55] then as "what we [in Gaul?] call rubia" (1.44); in the same chapter polygonos is given as another name for millefolium (1.28), and identified elsewhere as equivalent to verbena (10.5). Of the dozen or so Celtic plant names, ten are provided with or as synonyms for Greek or Latin names. A preoccupation with naming rather than description is a characteristic also of medieval herbals.[56] The problems of identifying plants may have been an intellectual attraction for Marcellus’s Renaissance editor Cornarius, whose botanical work emphasized the value of words over illustration.[57]

Another medieval emphasis foreshadowed in Marcellus is a concern for locating ingredients in their native environment, replacing the exotic flora and fauna prescribed in texts from antiquity with indigenous species. Recipes in both Marcellus and the medieval writers tend toward “polypharmacy,” or the use of a great number of ingredients in a single preparation. Many recipes in De medicamentis contain at least ten ingredients, and one, the antidotus Cosmiana (29.11), is compounded of 73.[58]

Marcellus is one of the likely sources for Anglo-Saxon leechcraft,[59] or at least drew on the shared European magico-medical tradition that also produced runic healing: a 13th-century wooden amulet from Bergen is inscribed with a charm in runes that resembles Marcellus’s Aisus charm.[60]

Therapeutic system

In The Cult of the Saints, Peter Brown contrasts the “horizontal” or environmental healing prescribed by Marcellus to the “vertical,” authoritarian healing of his countryman and contemporary St. Martin of Tours, known for miracle cures and especially exorcism. Since magic for medical purposes can be considered a form of faith healing, that is also not a distinction between the two; “rich layers of folklore and superstition,” writes Brown, “lie beneath the thin veneer of Hippocratic empiricism” in Marcellus.[61] Nor does the difference lie in the social class of the intended beneficiaries, for both therapeutic systems encompassed “country folk and the common people”[62] as well as senatorial landowners. At the Christian shrines, however, healing required submission to “socially chartered” authority;[63] in Marcellus, the patient or practitioner, often addressed directly as “you,” becomes the agent of his own cure.[64]

While the power of a saint to offer a cure resided within a particular shrine which the patient must visit, health for Marcellus lay in the interconnectivity of the patient with his environment, the use he actively made of herbs, animals, minerals, dung, language, and transformative processes such as emulsification, calcination and fermentation. In the prefatory epistle, Marcellus insists on the efficacy of remedia fortuita atque simplicia (remedies that are readily available and act directly), despite the many recipes involving more than a dozen ingredients; in the concluding Carmen, he celebrates ingredients from the far reaches of the empire and the known world (lines 41–67), emphasizing that the Roman practitioner has access to a “global” marketplace.[65]

The text

The standard text is that of Maximillian Niedermann, Marcelli de medicamentis liber, vol. 5 of the Teubner Corpus Medicorum Latinorum (Leipzig, 1916). The previous Teubner edition had been edited by Georg Helmreich in 1889.

References

- ↑ Carmélia Opsomer and Robert Halleux, “Marcellus ou le mythe empirique,” in Les écoles médicales à Rome. Actes du 2ème Colloque international sur les textes médicaux latins antiques, Lausanne, septembre 1986, edited by Philippe Mudry and Jackie Pigeaud (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1991), p. 160.

- ↑ In the Prima Scaligerana of 1740, cited by George W. Robinson, “Joseph Scaliger’s Estimates of Greek and Latin Authors,” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 29 (1918) p. 160.

- ↑ George Sarton, Introduction to the History of Science (1927), vol. 1, p. 391.

- ↑ Alf Önnerfors, “Marcellus, De medicamentis: Latin de science, de superstition, d’humanité,” in Le latin médical: La constitution d’un langage scientifique: réalités et langage de la médecine dans le monde romain, edited by Guy Sabbah (Université de Saint-Étienne, 1991), p. 397; Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), p. 51, note 4, as reprinted in Pristina Medicamenta: Ancient and Medieval Medical Botany, edited by Katherine E. Stannard and Richard Kay, Variorum Collected Studies Series (Aldershot 1999).

- ↑ J.F. Matthews, “Gallic Supporters of Theodosius,” Latomus 30 (1971), pp. 1084–1087.

- ↑ Spanish origin argued by K.F. Stroheker, Spanische Senatoren der spätrömischen und westgotischen Zeit, in Madrider Mitteilungen (1963) p. 121, note 75, cited and contradicted by J.F. Matthews, “Gallic Supporters of Theodosius,” Latomus 30 (1971) p. 1085. The De medicamentis seems to refer to Theodosius II, son of the emperor who had appointed Marcellus to office, suggesting that it was not circulated until his accession in January 408; see Alan Cameron, “A New Fragment of Eunapius,” Classical Review 17 (1967) 11.

- ↑ Codex Theodosianus vi.29.8 (May 395) and xvi.5.29 (November 395).

- ↑ Alf Önnerfors, “Marcellus, De medicamentis,” in Le latin médical (Université de Saint-Étienne, 1991), p. 397.

- ↑ For careful and thoroughly documented conjecture about the political career of Marcellus, see J.F. Matthews, “Gallic Supporters of Theodosius,” Latomus 30 (1971) 1073–1099.

- ↑ J.F. Matthews. “Gallic Supporters of Theodosius,” Latomus 30 (1971), p. 1086, who points out that earlier (in the period 379–88) Spaniards had predominated in Theodosius’s court.

- ↑ Codex Theodosianus vii.1.14.

- ↑ Codex Theodosianus xvi.5.29.

- ↑ Alan Cameron, “A New Fragment of Eunapius,” Classical Review 17 (1967) 10–11.

- ↑ Orosius 7.43.4: virum quendam Narbonensem inlustris sub Theodosio militiae, etiam religiosum prudentemque et gravem.

- ↑ For the text of that declaration in English translation, see article on Ataulf.

- ↑ J.F. Matthews, “Gallic Supporters of Theodosius,” Latomus 30 (1971), pp. 1085–1086.

- ↑ For instance, David Frye, “A Mutual Friend of Athaulf and Jerome,” Historia 40 (1991) 507–508, argues for the Gaul named Rusticus who is mentioned in Jerome’s epistles.

- ↑ Lynn Thorndike, The Place of Magic in the Intellectual History of Europe (New York 1905), p. 99,

- ↑ Lynn Thorndike, History of Magic and Experimental Science (Columbia University Press 1923), p. 584, without citing the specific letter.

- ↑ Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), p. 48; Alf Önnerfors, “Marcellus, De medicamentis,” in Le latin médical (Université de Saint-Étienne, 1991), pp. 398–399; Carmélia Opsomer and Robert Halleux, “Marcellus ou le mythe empirique,” in Les écoles médicales à Rome, (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1991).

- ↑ William D. Sharpe, introduction to “Isidore of Seville: The Medical Writings. An English Translation with an Introduction and Commentary,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 54 (1964), p. 14.

- ↑ E.H.F. Meyer, Geschichte der Botanik (Königsberg 1854–57), vol. 2, p. 300, cited by Önnerfors, p. 398.

- ↑ Thomas Habinek, The Politics of Latin Literature: Writing, Empire, and Identity in Ancient Rome (Princeton University Press, 1998); Roland Mayer, “Creating a Literature of Information in Rome,” in Wissensvermittlung in dichterischer Gestalt (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2005), pp. 227–241.

- ↑ Elizabeth Rawson, Intellectual Life in the Late Roman Republic (The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985), p. 170; Carmélia Opsomer and Robert Halleux, “Marcellus ou le mythe empirique,” in Les écoles médicales à Rome (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1991), p. 178.

- ↑ Literacy among farm workers at the managerial level was perhaps not meant to be surprising; according to an interlocutor in Varro’s De re rustica (2.18), a master ought to require his cattleman to read veterinary excerpts from the work of Mago the Carthaginian, available in Latin and Greek translations.

- ↑ De medicamentis prefatory epistle 3, edition of Maximillian Niedermann, Marcelli de medicamentis liber, vol. 5 of the Teubner Corpus Medicorum Latinorum (Leipzig, 1916), p. 3; discussion of general topic in Brendon Reay, “Agriculture, Writing, and Cato’s Aristocratic Self-Fashioning,” Classical Antiquity 24 (2005) 331–361.

- ↑ De medicamentis prefatory epistle 3.

- ↑ Alf Önnerfors, “Marcellus, De medicamentis,” in Le latin médical (Université de Saint-Étienne, 1991), p. 404–405.

- ↑ Alan Cameron, “A New Fragment of Eunapius,” p. 11; J.F. Matthews, “Gallic Supporters of Theodosius,” Latomus 30 (1971) p. 1086.

- ↑ Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), p. 50.

- ↑ Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity (University of Chicago Press, 1981), p. 117.

- ↑ Carmélia Opsomer and Robert Halleux, “Marcellus ou le mythe empirique,” in Les écoles médicales à Rome (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1991), p. 164.

- ↑ T.D. Barnes and R.W. Westall, “The Conversion of the Roman Aristocracy in Prudentius’ Contra Symmachus,” Phoenix 45 (1991) 50–61; Prudentius, Contra Symmachum 1.506–607.

- ↑ De civitate Dei 1.8; barbarian incursions are a subject relevant to Marcellus, living in 4th century Gaul under threat of the Visigoths.

- ↑ On the interpenetration of Christianity and traditional religion and culture in the 4th century, see for instance Clifford Ando, “Pagan Apologetics and Christian Intolerance in the Ages of Themistius and Augustine,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 4 (1996) 171–207.

- ↑ As by J.F. Matthews, “Gallic Supporters of Theodosius,” Latomus 30 (1971) p. 1086.

- ↑ In nomine Christi, De medicamentis 25.13.

- ↑ De medicamentis 21.2

- ↑ William M. Brashear, “The Greek Magical Papyri: ‘Voces Magicae’,” Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II, 18.5 (1995), p. 3435; see also David E. Aune, “Magic in Early Christianity: Glossolalia and Voces Magicae,” reprinted in Apocalypticism, Prophecy and Magic in Early Christianity: Collected Essays (2006).

- ↑ De medicamentis prefatory epistle 1.

- ↑ De medicamentis 15.106, p. 121 in Niedermann; Gustav Must, “A Gaulish Incantation in Marcellus of Bordeaux,” Language 36 (1960) 193–197; Pierre-Yves Lambert, “Les formules de Marcellus de Bordeaux,” in La langue gauloise (Éditions Errance 2003), p.179, citing Léon Fleuriot, “Sur quelques textes gaulois,” Études celtiques 14 (1974) 57–66.

- ↑ CIL XII.5336.

- ↑ In the amount of 2,100 solidi.

- ↑ John Matthews, Western Aristocracies and Imperial Court, A.D. 364–425 (Oxford University Press 1975), pp. 340–341, and “Gallic Supporters of Theodosius,” Latomus 30 (1971), p. 1087.

- ↑ William D. Sharpe, “Isidore of Seville: The Medical Writings,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 54 (1964), pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), p. 48.

- ↑ Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), p. 51, note 9.

- ↑ D.R. Langslow, “The Epistula in Ancient Scientific and Technical Literature, with Special Reference to Medicine,” in Ancient Letters: Classical and Late Antique Epistolography, edited by Ruth Morello and A.D. Morrison (Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 218–219 and 230.

- ↑ Jean-Marie André, “Du serment hippocratique à la déontologie de la médecine romaine,” Revue des études latines 83 (2005) 140–153.

- ↑ Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), p. 48.

- ↑ E.H.F. Meyer, “Geschichte der Botanik,” vol. 2 (1855) 305-315, as cited by Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), p. 52, note 23. Stannard finds about 350 plant names in all.

- ↑ Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), p. 50.

- ↑ Marco Formisano, “Veredelte Bäume und kultivierte Texte. Lehrgedichte in technischen Prosawerken der Spätantike,” in Wissensvermittlung in dichterischer Gestalt (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2005), pp. 295–312, with English summary.

- ↑ Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), pp. 47 and 50, also p. 53, notes 59 and 60, for extensive references.

- ↑ Also De medicamentis 9.21, where herbae polygoni is equivalent to sanguinalis, reiterated at 9.81.

- ↑ Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), p. 50.

- ↑ Sachiko Kusukawa, “Leonhart Fuchs on the Importance of Pictures,” Journal of the History of Ideas 58 (1997), pp. 423–426.

- ↑ Jerry Stannard, “Marcellus of Bordeaux and the Beginnings of the Medieval Materia Medica,” Pharmacy in History 15 (1973), p. 50.

- ↑ Wilfrid Bonser, The Medical Background of Anglo-Saxon England (1963) p. 252.

- ↑ Mindy LacLeod and Bernard Mees, Runic Amulets and Magic Objects (Boydell Press, 2006), pp. 117 online, 139, and 141.

- ↑ Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints (University of Chicago Press, 1981), pp. 113–114.

- ↑ De medicamentis, prefatory epistle 2, ab agrestibus et plebeis.

- ↑ Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints (University of Chicago Press, 1981), p. 116.

- ↑ Aline Rousselle, “Du sanctuaire au thaumaturge,” Annales 31 (1976) p. 1095, as cited by Brown, The Cult of the Saints, p. 116: “Il devient sujet actif de sa guérison. … L’homme est engagé, corps et esprit, dans sa propre guérison.”

- ↑ Peter Brown, The Cult of the Saints (University of Chicago Press, 1981) p. 118; Aline Rousselle, “Du sanctuaire au thaumaturge,” Annales 31 (1976) p. 1095, quoted by Brown, p. 116, refers to “une thérapie globale.”

|