Mandore (instrument)

|

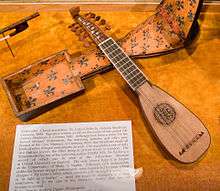

Picture of a mandore, with François de Chancy's tablature from Marin Mersenne's Harmonie Universelle, published 1636 in Paris. | |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| Related instruments | |

The mandore is a musical instrument, a small member of the lute family, teardrop shaped, with four, six courses of gut strings[1] and pitched in the treble range.[2] It was considered a new instrument in French music books from the 1580s,[3] but is descended from and very similar to the gittern.[4] It is considered ancestral to the modern mandolin. Other earlier instruments include the medieval European citole[5] and the Greek and Byzantine pandura.

The history of modern mandolins, mandolas and guitars are all intertwined.[6] The instruments shared common ancestor instruments.[7] Some instruments became fashionable widely, and others locally. Experts argue as to the differences; because many of the instruments are so similar but not identical, classifying them has proven difficult.

Some experts consider the mandore a forerunner to the mandolino[4] (also known as a Baroque mandolin), which in turn branched out into a family of mandolins that includes the Neapolitan mandolin, the Genoese mandolin, and the Cremonese mandolin.[8] Others consider that the mandore and mandolino may have been contemporary, with different names being used in different countries; the mandolino in Italy, the mandore in France.[9] It is also considered a forerunner or close relative of the 17th century mandola.[10]

Name controversy

The instrument has also been called mandora[11] or mandola in Italian,[12] vandola in Spanish [13] and mandörgen,[14] or quinterne[2][11] in German. Michael Praetorius used the names Mandürichen, Bandürichen, Mandoër, Mandurinichen, Mandüraen, and Pandurina.[15]

While the mandore and mandora have been considered equivalent names for the same instrument by some authors, there are authors who believe that mandora is strictly for a different kind of lute, tuned in the bass range.[2][16] For an article on the bass-range instruments, see Mandora.

The instrument has also been mistakenly called mandöraen instead of mandörgen by modern readers of Praetorius' book. However, the "raen" in the word is actually "rgen". The error is due to a lithographic fault in reproducing plate 16; that fault truncated the g into an a.[17] The error can be seen when comparing two different versions of the plate (compare the two versions in the file history).

A brief history

The Cantigas de Santa Maria shows 13th century instruments similar to lutes, mandores, mandolas and guitars, being played by European and Islamic players. The instruments moved from Spain northward to France[18][19] and eastward towards Italy by way of Provence.

Beside the introduction of the lute to Spain (Andalusia) by the Moors, another important point of transfer of the lute from Arabian to European culture was Sicily, where it was brought either by Byzantine or later by Muslim musicians.[20] There were singer-lutenists at the court in Palermo following the Norman conquest of the island from the Muslims, and the lute is depicted extensively in the ceiling paintings in the Palermo's royal Cappella Palatina, dedicated by the Norman King Roger II of Sicily in 1140.[20] His Hohenstaufen grandson Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor (1194 - 1250) continued integrating Muslims into his court, including Moorish musicians.[21] By the fourteenth century, lutes had disseminated throughout Italy and, probably because of the cultural influence of the Hohenstaufen kings and emperor, based in Palermo, the lute had also made significant inroads into the German-speaking lands.

Construction

Like the earlier gittern, the mandore's back and neck were in earlier forms carved out of a block of wood.[22] This "hollowed out construction" did still exist in the 16th century, according to James Tyler, but was becoming rare.[22] The method was being replaced by gluing curved staves together to form back, and adding a neck and peg box.[22]

From Mersenne: The normal length of a mandore is 11⁄2 feet long. It is built as a lute, with "strips of fir or other wood" ... "cut and bent into melon shape" to make a rounded back.[23] The fingerboard is on the same plane as the soundboard, with a bridge glued onto the soundboard. Strings are secured in the pegboard in the neck, pass over the fingerboard and soundboard and are tied to a flat bridge, which is glued to the soundboard.[24] The instrument may have as few as four strings or as many as six. It could also have four to six courses of two strings.[24] The soundhole was covered with a rose, either carved directly into the soundboard or glued in.[10]

Methods of playing

From Marin Mersenne, 1635: A musician plays the mandore "with the finger or the tip of a feather between thumb and index finger or tied to one of the other fingers."[23] "Those who make perfect use of the mandore would move the pick so fast over the strings that they seem to form even chords as they would be if played at the same time."[25]

Another early 17th century author, Michael Praetorius, agreed. He said, "They play either with a cittern-type quill plectrum, or with one finger - and this with the speed, clarity, and precision that we would expect from the use of three or four fingers. There are some players, however, who start to use two or more fingers once they are familiar with the instrument."[26]

Tuning

According to Praetorius

Michael Praetorius detailed four tunings for the Mandore in his book Syntagma Musicum in 1619. He listed three tunings (with one repeated) for tuning the mandore. His tuning illustrate tuning for both 4-stringed instruments and 5-stringed instruments.[4]

Fifths and fourths

The listed tunings using fifths and fourths between strings are:[4]

- C-G-C-G

- C-G-C-G-C

- G-D-G-D

Fourths and fifths

The listed tuning for fourths and fifths tuning is:[4]

- C-F-C-F-C

According to Mersenne

Mersenne indicates in his book that there were many ways to tune a mandore, but three ways predominated: tuning in unison, tuning with a lowered string, and tuning in a third.

Tuning in Unison

For a four string mandore, Mersenne said, "The fourth string is a fifth of the third; the third string is at the fourth of the second, and the second at a fifth from the treble string."[23] In other words, the mandore used a combination of fourths and fifths the courses of strings, such as c-g-c-g.[27]

Tuning with a lowered string

Mersenne indicated that this was less common than tuning in unison. To tune this way, "the treble string is lowered a tone, so to make a fourth with the third string."[28] In other words, going from tuning c-g-c-g to c-g-c-f.

Tuning in a third

In tuning a third, one "lowers the treble string down a minor third, so it makes a major third with the third."[28] An example is going from c-g-c-g to c-g-c-e.

According to the Skene Manuscript

The tunes in the Skene Manuscript are for a mandore tuned in fourths and fifths. Dauney points out in his editing of the Skene Manuscript that the tablature is written strangely, that although it is tabbed for a four-string instrument, it is marked under the bottom line, indicating a five-string instrument:[29]

- A-D-A-D-A

and also an older lute tuning in fourths (except between F and A, which is a third):[29]

- C-F-A-D-G

Relationship to other instruments

Mandore compared to lute

Marin Mersenne ends his section on the mandore in his book Harmonie Universelle by saying, "It is nothing but an abbreviated lute."[25] He said this in the context that one could look at his section on the lute for applicable information. Lutes were larger than mandores, which Mersenne described as miniature. Lutes had more courses of strings and were not restricted to the high treble range, but could play into the bass range.

Earlier in the section he compared the lute to the mandore. "Now although the mandore has only four strings, nevertheless one plays it rather above all that is played in a lute, whose chorus it covers because of the liveliness and sharpness of its tone, which penetrates and so preoccupies the ear that the lutes have trouble being heard."[30] He said that good mandore players were prone to speedy picking, blurring notes together in a rush of speed.[25]

Mandore compared to treble lute

Mandores and treble lutes were tuned differently: treble lutes from the 16th and early 17th centuries had six or more courses of strings, tuned to a "4th, a 4th, a major third, a 4th, a fourth."[31]

Though a member of the lute family, it has been said that the mandore was not a treble lute, which had six or more courses and was tuned the same way as mainstream lutes[32]

Mandore compared to mandola and mandolino

To a layman, images of the mandola and mandore show no obvious differences, when comparing two instruments from the same time period. One visible difference was that the mandola and mandolino commonly used double courses of strings, where illustrations of the mandore commonly show single strings.[1] A less visible difference was in the tuning: the Italian mandola and smaller mandolino were tuned entirely in fourths, the mandola using e-a-d-g (or if using a 5 or 6 course instrument g-b-e-a-d-g); the French mandore used combinations of fourths and fifths, such as c-g-c-g or c-f-c-f. .[1][32] As the instruments developed, they became physically less similar. By the 17th century, makers such as Antonio Stradivarius had two styles of instrument patterns, with the mandola having strings almost twice as long as the mandolino's.[33]

Two styles of mandolas have made it into museums, flat-backed and bowl-backed. Flat-backed mandolas resemble citterns. Bowl-backed mandolas resemble mandores. One example that has survived of a bowl-backed mandola is that made by Vicenti di Verona in 1696, held by the Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, Hungary. By looks alone, telling the bowl-backed mandola from the mandore can be a challenge.

Mandore compared to Neapolitan mandolin

Pictures and illustrations of the mandore show an instrument that at a casual look, appears very similar to lutes and the later mandolins. The mandore differs from the Neapolitan mandolin in not having a raised fretboard and in having a flat soundboard.[1] Also It was strung with gut strings, attached to a bridge that is glued to the soundboard[34] (similar to that of a modern guitar). It was played with the fingertips.

In contrast, the Neapolitan mandolin's soundboard is bent.[35] It uses metal strings attached to the end of the instrument, crossing over a bridge that pushes downwards into the bent soundboard.[35]

The differences in design reflect progress in a technological push for louder instruments.[36] If the mandore's gut-strings were tightened too much they broke, but metal strings could pull the fixed bridge off the soundboard, or damage the soundboard. The bend in the Neapolitan's soundboard (new technology at the time) let the soundboard take the pressure of metal strings, driving the bridge down into the soundboard.[36] The result was a louder instrument with less fragile strings. The metal strings are played with a plectrum, creating even more volume.[37]

Mandolins are tuned in fifths, typically g-d-a-e for a four string mandolin.

Mandore compared to bandola

Another group of related instruments to the mandore are the vandola or bandola, the bandurria and the bandolim, of Spanish origin, also played in Portugal and South America.

In 1761, Joan Carles Amat said of the vandola, in his Guitarra espanola, y vandola, "And it should be noted that the vandola with six courses is described here, because it is the more perfect form of the instrument, and better known and more widely used at this time than that with four or five courses".

Mandore compared to the Scottish mandora

A principal source of music for the Scottish variant of the instrument can be found in The Ancient Melodies of Scotland by William Dauney. This book is a history of Scottish music, and contains some information on the mandora. Dauney makes it clear that the mandora (which he also calls the mandour) for which the tunes in the Skene Manuscript are written, is the same instrument that Mersenne called the mandore.[29]

Composers

- Renaissance mandore: Martin Agricola, Pierre Brunet, Adrian Le Roy, Ottomar Luscinius, Sebastian Virdung et al.

- 17th century mandora: François de Chancy, Henry François de Gallot, Valentin Strobel, Maitrise von François-Pierre Goy et al.

- 18th century mandora: Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, Giuseppe Antonio Brescianello, Johann Paul Schiffelholz et al.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mandore (instrument). |

Research papers and books

- A Reprint of François Chancy's Tablature de Mandore, along with modern sheet music with Mandore tabs, and a research paper on the Mandore by Jeffrey C. Lambert

- Important academic paper by James Tyler laying out a detailed view of the mandore's history

- Online text of The Ancient Melodies of Scotland by William Dauney, with mandore tablature from the Skene manuscript

Web pages

- Page (in French) explores differences between Mandore and Mandolino

- Page by the Ensemble Gabriele Leone compares "French Baroque" mandore with other baroque instruments

- Many pictures of vintage mandolins and pre-mandolins laid out side by side

- Meteora, Barlaam Monastery, King David's XVI-cent. fresco with mandore.

- Medici's court, musician with mandore.

- Meteora, Barlaam Monastery, King David's XVI-cent. fresco with mandore.

- Brief history with pictures; shows relationship between mandolin, gittern and mandore

- Picture of a Stradivarius mandolin or mandolino, from Cremona, Italy, 1680; very similar to the mandore

- Comparisons of mandolin type instruments

- Music for the mandore

- Mandore's History

- Old tabulatures for mandore

Museum Examples

- Good picture of a mandore in the Victoria and Albert Museum, England

- About mandore in the Victoria and Albert Museum

- Page from the French museum Médiathèque de la Cité de la musique, Paris with a 17th-century mandore, with pictures from several angles

- Another page from the French museum Médiathèque de la Cité de la musique, Paris featuring a 17th-century mandore, with pictures from several angles

- A 1655 mandore, in the collection of the Future Museum, Southwest Scotland

- A 1717 mandore by Joannes Schorn of Salisburgh in the collection of the University of Edinburgh Musical Instruments Museum

- An 18th-century mandore labelled Michel Angelo Bergonzi figlio di Carlo fece in Gremona l'anno 1755, from the collection of the Future Museum, Southwest Scotland

- Another Bergonzi mandore in the collection of the University of Edinburgh Musical Instruments Museums Edinbugh

- Another 18th century mandore from the Future Museum, Southwest Scotland, labelled Petrus Merighi fecit Parmae 1767

Literature

- D. Gill: "Mandore and Calachon", FoMRHI Quarterly, no. 19 (1980), p. 61–63

- D. Gill: "Mandores and Colachons", Galpin Society Journal, p. xxxiv (1981), p. 130–41

- D. Gill: "Alternative Lutes: the Identity of 18th-Century Mandores and Gallichones", The Lute, xxvi (1986), p. 51–62

- D. Gill: "The Skene Mandore Manuscript", The Lute, xxviii (1988), 19–33

- D. Gill: "Intabulating for the Mandore: Some Notes on a 17th-Century Workbook", The Lute, xxxiv (1994), p. 28–36

- C. Hunt: "History of the Mandolin"; Mandolin World News Vol 4, No. 3, 1981

- A. Koczirz: "Zur Geschichte der Mandorlaute"; Die Gitarre 2 (1920/21), p. 21–36

- Marin Mersenne: Harminie Universelle: The Books on Instruments, Roger E. Chapman trans. (The Hague, 1957)

- E. Pohlmann: Laute, Theorbe, Chitarrone; Bremen, 1968 (1982)

- M. Prynne: "James Talbot's Manuscript, IV: Plucked Strings – the Lute Family", Galpin Society Journal, xiv (1961), p. 52–68

- Tyler, James (1981). "The Mandore in the 16th and 17th Centuries" (PDF). Early Music (January 1981) 9 (1): 22–31. doi:10.1093/earlyj/9.1.22. JSTOR 3126587.

- James Tyler and Paul Sparks: The Early Mandolin: the Mandolino and the Neapolitan Mandoline, Oxford Early Music Series, Clarendon Press 1992, ISBN 978-0198163022

- James Tyler: The Early Guitar: a History and Handbook Oxford Early Music Series, Oxford University Press, 1980, ISBN 978-0193231825

References

- McDonald, Graham (2008). The Mandolin Project. Jamison, Australia: Graham McDonald Stringed Instruments. ISBN 978-0-9804762-0-0.

- Mersenne, Marin; Chapman, Roger E (1957) [1635]. Harmonie Universelle. The Hague, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Tyler, James; Sparks, Paul (1992). The Early Mandolin. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-816302-9.

- 1 2 3 4 McDonald 2008, pp. 7–8

- 1 2 3 "Mandore [Mandorre].". The Groves Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Retrieved 2015-03-21.

- ↑ McDonald 2008, p. 7

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tyler, James (1981). "The Mandore in the 16th and 17th Centuries" (PDF). Early Music (January 1981) 9 (1): 22–31. doi:10.1093/earlyj/9.1.22. JSTOR 3126587. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- ↑ McDonald 2008, pp. 4–8

- ↑ McDonald 2008, p. 1

- ↑ McDonald 2008, pp. 1–14

- ↑ McDonald 2008, pp. 8–14

- ↑ Dave Hynds. "Mandolins: A Brief History". mandolinluthier.com. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- 1 2 McDonald 2008, pp. 9–10

- 1 2 Nikolova, Kőnemann (2000). The Illustrated Enclyclopedia of Musical Instruments From all eras and regions of the world. Bulgaria: Kibea Publishing Company. p. 164. ISBN 3-8290-6079-3.

- ↑ Whitney, William Dwight (1906). The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia. New York: The Century Company. p. 3606.

- ↑ The Harvard Dictionary of Music, page 484

- ↑ Lambert, Jeffrey C. "François Chancy's Tablature de Mandore a Major Document" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- ↑ James Tyler. "Mandore". In Macy, Laura. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- ↑ Alburger, Mark. "Giorgio Mianerio (1535–1582) — Old and New". Music History, Thursday January 13, 8535. Retrieved 2010-11-11.

- ↑ "Mandore [Mandorre]". musicviva.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- 1 2 "Mandore Boissart". The Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ↑ Didier Le Roux and Jean-Paul Bazin. "History of the Mandolin: The French baroque : the mandore". ensemble-gabriele-leone.org. Retrieved 2010-11-06.

- 1 2 Colin Lawson and Robin Stowell, The Cambridge History of Musical Performance, Cambridge University Press, Feb 16, 2012

- ↑ Roger Boase, The Origin and Meaning of Courtly Love: A Critical Study of European Scholarship, Manchester University Press, 1977, p. 70-71.

- 1 2 3 Tyler & Sparks 1992, pp. 6–7

- 1 2 3 Mersenne & Chapman 1957, p. 130

- 1 2 "Mandore [Mandorre]". Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- 1 2 3 Mersenne & Chapman 1957, p. 134

- ↑ Praetorius, Michael; Crookes, David Z (1986) [1614]. Syntagma Musicum. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816260-5.

- ↑ McDonald 2008, pp. 8–10

- 1 2 Mersenne & Chapman 1957, p. 131

- 1 2 3 Dauney, William (1838). "The Skene Manuscript". Ancient Scotish Melodies, from A Manuscript of the Reign of King James VI. with An Introductory Enquiry illustrative of the History of the Music of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Printing and Publishing Company. (the Skene manuscript)

- ↑ Mersenne & Chapman 1957, p. 133

- ↑ Tyler & Sparks 1992, p. 5

- 1 2 "Mandolin [mandola, mandoline, mandolino]". The Groves Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ McDonald 2008, p. 10

- ↑ McDonald 2008, p. 8

- 1 2 McDonald 2008, p. 11

- 1 2 McDonald 2008, p. 14

- ↑ McDonald 2008, pp. 11, 14

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||