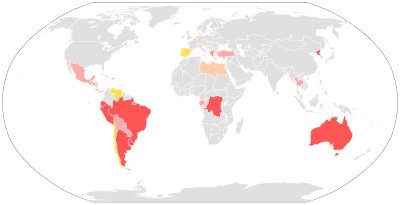

Compulsory voting

Compulsory voting, not enforced.

Compulsory voting, enforced (only men).

Compulsory voting, not enforced (only men).

Historical: the country had compulsory voting in the past.

Compulsory voting is a system in which electors are obliged to vote in elections or attend a polling place on voting day. If an eligible voter does not attend a polling place, or lodge a postal vote, he or she may be subject to a penalty such as fines or community service. As of August 2013, 22 countries, including 12 Latin American countries, have laws for compulsory voting and 11 of these 22 countries enforce these laws in practice.[1]

History

Athenian democracy held that it was every citizen's duty to participate in decision making, but attendance at the assembly was voluntary. Sometimes there was some form of social opprobrium to those not participating. For example, Aristophanes's comedy Acharnians 17–22, in the 5th century BC, shows public slaves herding citizens from the agora into the assembly meeting place (pnyx) with a red-stained rope. Those with red on their clothes were fined.[2] This usually happened if fewer than 6,000 people were in attendance, and more were needed for the assembly to continue. In fact, tools that enforced assembly attendance may have been inspired by Solon's law against neutrality and acted as a precedent of ostracism; like with ostracism, the obligation to participate was generally aimed at preventing the subversion of democratic politics by oligarchic or tyrannical forces.[3]

Arguments for

Supporters of compulsory voting generally look upon voter participation as a civic duty, similar to taxation, jury duty, compulsory education or military service; one of the 'duties to community' mentioned in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[4] They believe that by introducing an obligation to vote, it helps to overcome the occasional inconvenience that voting imposes on an individual in order to produce governments with more stability, legitimacy and a genuine mandate to govern, which in turn benefits that individual even if their preferred candidate or party isn't elected to power.

Compulsory voting systems can confer a high degree of political legitimacy because they result in high voter turnout.[5] The victorious candidate represents a majority of the population, not just the politically motivated individuals who would vote without compulsion.[6]

Compulsory voting also prevents disenfranchisement of the socially disadvantaged. Australian academic and supporter of compulsory voting, Lisa Hill, has argued that a prisoner’s dilemma situation arises under voluntary systems for marginalised citizens: it seems rational for them to abstain from voting, under the assumption that others in their situation are also doing so, in order to conserve their limited resources. However, since these are the people who are in most need of political representation, this decision is also irrational. Hill argues that the introduction of compulsory voting removes this dilemma.[7]

In a similar way that the secret ballot is designed to prevent interference with the votes actually cast, compelling voters to the polls for an election reduces the impact that external factors may have on an individual's capacity to vote such as the weather, transport, or restrictive employers. If everybody must vote, restrictions on voting are easily identified and steps are taken to remove them. If voters do not want to support any given choice, they may cast spoilt votes or blank votes. According to compulsory voting supporters, this is preferred to not voting at all because it ensures there is no possibility that the person has been intimidated or prevented from voting should they wish. In certain jurisdictions, voters have the option to vote none of the above if they do not support any of the candidates to indicate clear dissatisfaction with the candidate list rather than simple apathy at the whole process.

Another perceived benefit of the large turnout produced by compulsory voting is that it becomes more difficult for extremist or special interest groups to get themselves into power or to influence mainstream candidates. Under a non-compulsory voting system, if fewer people vote then it is easier for lobby groups to motivate a small section of the people to the polls and influence the outcome of the political process. The outcome of an election where voting is compulsory reflects more of the will of the people (Who do I want to lead the country?) rather than reflecting who was more able to convince people to take time out of their day to cast a vote (Do I even want to vote today?).

Other perceived advantages to compulsory voting are the stimulation of broader interest politics, as a sort of civil education and political stimulation, which creates a better informed population. Also, since campaign funds are not needed to goad voters to the polls, the role of money in politics decreases. High levels of participation decreases the risk of political instability created by crises or charismatic but sectionally focused demagogues.[6]

There is also a correlation between compulsory voting, when enforced strictly, and improved income distribution, as measured by the Gini coefficient and the bottom income quintiles of the population.[8]

Arguments against

Voting may be seen as a civic right rather than a civic duty. While citizens may exercise their civil rights (free speech, right to an attorney, etc.) they are not compelled to. Furthermore, compulsory voting may infringe other rights. For example, Jehovah's Witnesses[9] and most Christadelphians believe that they should not participate in political events. Forcing them to vote ostensibly denies them their freedom of religious practice. In some countries with compulsory voting, Jehovah's Witnesses and others may be excused on these grounds. If however they are forced to go to the polling place, they can still use a blank or invalid vote.

Similarly, compulsory voting may be seen as an infringement of Article 2 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which guarantees freedom of political opinion and thus the right of citizens to believe in a political system other than a democratic one, such as an absolute monarchy. However, it may also be argued that citizens may legitimately be required to vote since the right to believe in a different political system does not conflict with the obligation to conform with legal requirements of the system in place.

Another argument against compulsory voting, prevalent among legal scholars in the United States, is that it is essentially a compelled speech act, which violates freedom of speech because the freedom to speak necessarily includes the freedom not to speak.[10]

Some do not support the idea of voters being compelled to vote for candidates they have no interest in or knowledge of. Others may be well-informed, but have no preference for any particular candidate, or may have no wish to give support to the incumbent political system. In compulsory voting areas, such people often vote at random simply to fulfill legal requirements: the so-called donkey vote may account for 1–2% of votes in these systems, although due to the law of large numbers, this should have no effect on the result. Similarly, citizens may vote with a complete absence of knowledge of any of the candidates or deliberately skew their ballot to slow the polling process or disrupt the election.

The Australian system of preferential voting means a person's vote usually ends up favouring one of the two main political parties, even though the voter may not wish to advantage either. Former Australian opposition leader Mark Latham urged Australians to lodge blank votes for the 2010 election. He stated the government should not force citizens to vote or threaten them with a fine.[11] At the 2013 federal election, despite the threat of a non-voting fine of up to $170,[12] there was a turnout of only 92%,[13] of whom 6% lodged either informal or blank ballot papers.[14] In the corresponding Senate election, contested by over 50 groups,[15] legitimate manipulation of the group voting tickets and single transferable vote routing resulted in the election of one senator, Ricky Muir of the Australian Motoring Enthusiast Party, who had initially received only 0.5% of first-preference support.[16] The system was accused of undermining the entitlement of voters "to be able to make real choices, not forced ones—and to know who they really are voting for."[17]

Research

A study of a Swiss canton where compulsory voting was enforced found that compulsory voting significantly increased electoral support for leftist policy positions in referendums by up to 20 percentage points.[18] Another study found that the effects of universal turnout in the United States would likely be small in national elections, but that universal turnout could matter in close elections, such as the presidential elections of 2000 and 2004.[19] Research on compulsory voting in Australia found that it increased the vote shares and seat shares of the Australian Labor Party by 7 to 10 percentage points and led to greater pension spending at the national level.[20]

Current use by countries

As of August 2013, 22 countries were recorded as having compulsory voting.[1] Of these, only 10 countries (additionally one Swiss canton and one Indian state) enforce it. Of the 30 member states of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 10 had forms of compulsory voting.[21]

Enforced

These are the countries and sub-national entities that enforce compulsory voting:

- Argentina – Introduced in 1912.[22] Compulsory for citizens between 18 and 70 years old, non-compulsory for those older than 70 and between 16 and 18. (However, in primaries, citizens under 70 may refuse to vote, if they formally express their decision to the electoral authorities, at least 48 hours before the election. This is valid only for the subsequent primary, and needs to be repeated each time the voter wishes not to participate.)

- Australia – Introduced in 1924.[22] Compulsory for federal and state elections for citizens aged 18 and above. The requirement is for the person to enrol, attend a polling station and have their name marked off the electoral roll as attending, receive a ballot paper and take it to an individual voting booth, mark it, fold the ballot paper and place it in the ballot box. The act does not explicitly state that a choice must be made, it only states that the ballot paper be 'marked'. According to the act how a person marks the paper is completely up to the individual. In some states, local council elections are also compulsory.[23] At the 2010 Tasmanian state election, with a turnout of 335,353 voters, about 6,000 people were fined $26 for not voting, and about 2,000 paid the fine.[24] A postal vote is available for those for whom it is difficult to attend a polling station.

- Brazil[25] – Compulsory for literate citizens between 18 and 70 years old. Non-compulsory for Brazilians aged 16–17 or over 70 or illiterate citizens of any age. A justification form for not voting can be filled at election centers and post offices.

- Cyprus – Introduced in 1960.[22]

- Ecuador – Introduced in 1936.[22] Compulsory for citizens between 18 and 65 years old; non-compulsory for citizens aged 16–18, illiterate people, and those older than 65.

- Indian state Gujarat passed a bill by legislative assembly in 2009 and later again in 2011 with some modifications, which was approved by the Governor of Gujarat in November 2014, making voting compulsory in local civic body elections and a punishment for not voting.[26] The Government of Gujarat chose not to notify the law or enforce it initially, citing legal implications and difficulty in enforcement.[27] But later in June 2015, the government decided to notify and enforce the law.[28]

- Liechtenstein

- Luxembourg – Voluntary for those aged over 70.

- North Korea – Everyone over age 17 is required to vote. However, only one candidate appears on the ballot. Voting is designed to track who is and isn't in the country. Dissenting votes are possible but lead to repercussions for voters.[29]

- Nauru – Introduced in 1965.[22]

- Peru[30] – Introduced in 1933.[22] Compulsory for citizens between 18 and 70 years old, non-compulsory for those older than 70.

- Singapore – Compulsory for citizens above 21 years old as of the date of the last electoral roll revision. For example, the 2015 election has the cut-off date on 1 July 2015.

- Uruguay – Introduced in 1934, but not put into practice until 1970.[22]

- Schaffhausen canton in Switzerland has compulsory voting – Introduced to Switzerland in 1904, but abolished in all other cantons by 1974.[22]

Not enforced

Countries that have compulsory voting on the law books but do not enforce it:

- Belgium – Compulsory for every citizen from age 18 to present themselves in a polling station, legal sanctions still exist, but only the sanctions for absent appointed polling station staff have been enforced by prosecutors since 2003.[31][32]

- Bolivia – Introduced in 1952.

- Costa Rica

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Dominican Republic – Compulsory from the age of 18.

- Egypt

- Gabon

- Greece

- Guatemala

- Honduras

- Lebanon – Men only[33]

- Libya

- Mexico

- Panama

- Paraguay – Compulsory for citizens between 18 and 75 years old, non-compulsory for those older than 75.

- Thailand

- Turkey – The ₺22 fine in law is generally not enforced.[34]

Past use by countries

- Austria - Introduced in 1924 and exercised during the 1925 presidential elections

- Chile - Removed from the Constitution and replaced with voluntary voting in 2009; voluntary voting was regulated and put into practice in 2012; all eligible citizens aged over 17 are automatically enrolled (only those over 18 on election day may vote; although the act of voting itself is voluntary, polling officer duties are not if chosen by a commission for the job)[35]

- Fiji - Abolished in 2014 [36]

- Italy - Introduced in 1945, abolished in 1993.

- Netherlands - Introduced in 1917 along with universal suffrage, abolished in 1967.

- Portugal - Portuguese constitutional referendum, 1933, not enforced.

- Spain - 1907–1923, but not enforced

- US State of Georgia - In 1777 (10 years before the adoption of the federal Constitution of 1787)[37] This provision was omitted from the revised Georgia constitution of 1789.

- Venezuela - Removed in 1993[38]

Measures to encourage voting

Although voting in a country may be compulsory, penalties for failing to vote are not always strictly enforced. In Australia[39] and Brazil, providing a legitimate reason for not voting (such as illness) is accepted. In Argentina, those who were ill on voting day are excused by requesting a doctor to prove their condition; those over 500 km (310 mi) away from their voting place are also excused by asking for a certificate at a police station near where they are.[40] Belgian voters can vote in an embassy if they are abroad or can empower another voter to cast the vote in their name; the voter must give a "permission to vote" and carry a copy of the eID card and their own on the actual elections.

States that sanction nonvoters with fines generally impose small or nominal penalties. However, penalties for failing to vote are not limited to fines and legal sanctions. Belgian voters who repeatedly fail to vote in elections may be subject to disenfranchisement. Singapore voters who fail to vote in a general election or presidential election will be subjected to disenfranchisement until a valid reason is given or a fine is paid. Goods and services provided by public offices may be denied to those failing to vote in Peru and Greece. In Brazil, people who fail to vote in an election are barred from obtaining a passport and subject to other restrictions until settling their situation before an electoral court or after they have voted in the two most recent elections. If a Bolivian voter fails to participate in an election, the person may be denied withdrawal of the salary from the bank for three months.[41][42]

A postal vote may be available for those for whom it is difficult to attend a polling station.

See also

References

- 1 2 World Factbook: Suffrage at Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 16 August 2013

- ↑ Malkopoulou, Anthoula (2015). The History of Compulsory Voting in Europe: Democracy's Duty? London: Routledge, pp.52-54

- ↑ Ibid. pp.49-52

- ↑ Archived February 17, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Levine, Jonathan The Case for Compulsory Voting, The National Interest 2 November 2012

- 1 2 Lijphart, Arend (1997) "Unequal Participation: Democracy's Unresolved Dilemma", The American Political Science Review 91(1): 8–11, (Subscription required for full access.)

- ↑ Hill, L 2002 ‘On the reasonableness of compelling citizens to ‘vote’: The Australian case’, Political Studies, vol. 50, no. 1, pp.88-89

- ↑ Chong, Alberto and Olivera, Mauricio, "On Compulsory Voting and Income Inequality in a Cross-Section of Countries", Inter-American Development Bank Working Paper, May 2005.

- ↑ "Political Neutrality". Jehovah's Witnesses. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ↑ Note, The Case for Compulsory Voting in the United States, 121 Harv. L. Rev. 591, 601–603 (2007). Harvard is one of several law schools at which students may submit articles for publication in the school's law review but only anonymously in the form of "Notes" (with a capital "N").

- ↑ "Latham at Large". Channel Nine. 12 August 2010. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- ↑ What happens if I do not vote? at Australian Electoral Commission

- ↑ Turnout by State at Australian Electoral Commission

- ↑ Informal Votes by State at Australian Electoral Commission

- ↑ First Preferences by Group at Australian Electoral Commission

- ↑ http://vtr.aec.gov.au/SenateStateFirstPrefs-17496-VIC.htm

- ↑ Colebatch, Tim Bringing a barnyard of crossbenchers to heel The Age, Melbourne, 10 September 2013

- ↑ Bechtel, Michael M.; Hangartner, Dominik; Schmid, Lukas (2015-10-01). "Does Compulsory Voting Increase Support for Leftist Policy?". American Journal of Political Science: n/a–n/a. doi:10.1111/ajps.12224. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ↑ Sides, John; Schickler, Eric; Citrin, Jack (2008-09-01). "If Everyone Had Voted, Would Bubba and Dubya Have Won?". Presidential Studies Quarterly 38 (3): 521–539. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2008.02659.x. ISSN 1741-5705.

- ↑ Fowler, Anthony (2011-04-23). "Electoral and Policy Consequences of Voter Turnout: Evidence from Compulsory Voting in Australia". Rochester, NY. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1816649.

- ↑ Evans, Tim. Compulsory Voting in Australia, Australian Electoral Commission. Retrieved on 2007-01-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Compulsory Voting". IDEA. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ↑ Australian Electoral Commission Site On Rules Governing Compulsory Voting In Federal and State Elections http://www.aec.gov.au/Voting/Compulsory_Voting.htm

- ↑ Tasmanian political leaders face off in televised debate 2014-02-27

- ↑ Timothy J. Power: Compulsory for Whom? Mandatory Voting and Electoral Participation in Brazil, 1986–2006, in: Journal of Politics in Latin America. S. 97–122

- ↑ "Gujarat first state to make voting must in local body elections". The Times of India. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ↑ Dave, Kapil (12 November 2014). "Gujarat govt gets cold feet after making voting compulsory in civic body poll". The Times of India. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ↑ "Gujarat to introduce compulsory voting in upcoming local bodies polls". Firstpost. 2015-06-18. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ↑ "The Economist explains: How North Korea's elections work". The Economist. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ "Constitucion Política Del Perú". Tc.gob.pe. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- ↑ Niet-stemmers riskeren geen straf (in Dutch) De Morgen 06/06/2009

- ↑ http://www.7sur7.be/7s7/fr/1502/Belgique/article/detail/1067652/2010/02/15/Vers-la-fin-du-vote-obligatoire.dhtml

- ↑ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2123.html#le

- ↑ http://www.turkiyegazetesi.com.tr/gundem/145455.aspx

- ↑ Compulsory voting eliminated in Chile Blog post at allvoices.com, 21 December 2011

- ↑ http://www.radioaustralia.net.au/international/radio/onairhighlights/fiji-to-drop-compulsory-voting-lower-age-for-2014

- ↑ "Constitution of Georgia, 5 February 1777". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ↑ Elliot Frankal (2005-07-04). "Compulsory voting around the world | Politics | guardian.co.uk". London: Politics.guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- ↑ "Electoral Backgrounder: Compulsory Voting" (PDF). September 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ↑ "Elecciones 2015: toda la información" (in Spanish). Télam. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ↑ http://www.thenews.com.pk/Todays-News-13-20732-Of-31-countries-with-compulsory-voting-a-dozen-actually-enforce-it

- ↑ "Compulsory voting around the world", The Guardian, 4 July 2005

External links

- International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance – Compulsory voting information

- Suffrage – The CIA World Factbook

- Compulsory Voting, Not

- – Australian Electoral Commission – Electoral Backgrounder – Compulsory Voting

- – Australian Electoral Commission Australian Electoral Commission

- European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) Sessions of Workshops 2007, Workshop No.7: Compulsory Voting: Principle and Practice – academic conference papers on compulsory voting