Malayan Emergency

| Malayan Emergency Darurat Malaya 馬來亞紧急状态 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the decolonisation of Asia and the Cold War | |||||||||

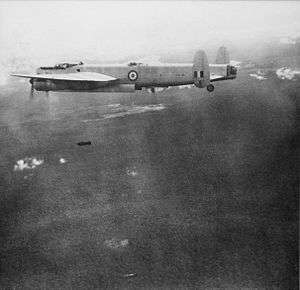

Australian Avro Lincoln bomber dropping 500lb bombs on communist rebels in the Malayan jungle (c. 1950) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Anti-communist forces:

Supported by: |

Communist forces: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

250,000 Malayan Home Guard troops 37,000 Special Constables 24,000 Federation Police |

Up to 150,000 Min Yuen (30,000 to 40,000 likely) *

| ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Killed: 1,346 Malayan troops and police 519 British military personnel Wounded: 2,406 Malayan and British troops/police |

Killed: 6,710 Wounded: 1,289 Captured: 1,287 Surrendered: 2,702 | ||||||||

| Civilian casualties: 2,478 killed, 810 missing | |||||||||

| ||||||

The Malayan Emergency (Malay: Darurat) was a Malayan guerrilla war fought between Commonwealth armed forces and the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), the military arm of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), from 1948–60.

"Malayan Emergency" was the colonial government's term for the conflict. The MNLA termed it the Anti-British National Liberation War.[2] The rubber plantations and tin-mining industries had pushed for the use of the term "emergency" since their losses would not have been covered by Lloyd's insurers if it had been termed a "war".[3]

Despite the communists' defeat in 1960, communist leader Chin Peng renewed the insurgency in 1967; it lasted until 1989, and became known as the Communist Insurgency War (Second Malayan Emergency). Although Australian and British armed forces had largely withdrawn from Malaya (by then known as Peninsular Malaysia) years earlier, the insurgency still failed.

Origins

Economic issues

The Malayan economy relied on the export of tin and rubber, and was therefore vulnerable to any shifts in the world market. When the British took control of the Malayan economy, they imposed taxes on some Malayan goods, which impacted the traditional economy. This led to an increase in poverty for the Malayan people.[4] Many Chinese people found employment in tin mines or fields or responsible for the trade of materials.[5] This heightened the inter-ethnic tensions as the Malayan people found that ethnic Chinese had replaced them in certain jobs and work became more difficult to find. This forced many Malay nationals into the rubber industry, which in turn was heavily dependent upon the volatile world prices.[4]

Economic tension intensified during the Second World War. The Japanese occupation of Malaya began in 1941 and from that point onwards the “export of primary products was limited to the relatively small amounts required for the Japanese economy.”[6] This led to large areas of rubber plantations being abandoned and many mines closing. The latter was progressively affected by a shortage of spare parts for machines.[6] Rice imports, which made up a large portion of the Malayan diet, fell rapidly due to limited trade and thus the population was forced to focus their efforts on producing enough food to stay alive.[7] Many people believed that the British would soon return and ‘save’ them so they did not attempt to learn the farming skills that would be essential for survival.[8] This then led to severe famine in Malaya from 1942.

The withdrawal of Japan at the end of World War II left the Malayan economy disrupted. Problems included unemployment, low wages, and high levels of food inflation, well above the healthy rate of 2–3%. The Malayan Communist Party began to use the failing economy as a tool of propaganda against the British. The British had not addressed the under-lying economic problems that were now worse within Malaya than they had ever been.[6] There was considerable labour unrest and a large number of strikes occurred between 1946 and 1948. One example of this was a 24-hour general strike organised by the MCP on 29 January 1946.[9] During this time, the British administration was attempting to repair Malaya's economy—revenue from Malaya's tin and rubber industries was important to Britain's own post-war recovery. Protesters were dealt with harshly, by measures including arrests and deportations. In turn, protesters became increasingly militant. In 1947, alone, the Chinese communists in Malaya organised a further 300 strikes.[9]

First point of war

On 16 June 1948, the first overt act of the war took place when three European plantation managers were killed at Sungai Siput, Perak.[10] The Malayan Communist Party (MCP) was ordered to go on the offensive in accordance with Soviet global strategy.[11]

The British brought emergency measures into law, first in Perak in response to the Sungai Siput incident and then, in July, country-wide. Under the measures, the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and other leftist parties were outlawed and the police were given the power to imprison without trial communists and those suspected of assisting them. The MCP, led by Chin Peng, retreated to rural areas and formed the MNLA, also known as the Malayan Races Liberation Army (MRLA) or the Malayan People's Liberation Army (MPLA). The MNLA began a guerrilla campaign, targeting mainly the colonial resource extraction industries, which in Malaya were the tin mines and rubber plantations.

The MNLA was partly a re-formation of the Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), the MCP-led guerrilla force which had been the principal resistance in Malaya against the Japanese occupation. The British had secretly trained and armed the MPAJA during the later stages of World War II. Disbanded in December 1945, the MPAJA officially turned all of its weapons in to the British Military Administration. Members who agreed to disband were offered economic incentives; however, around 4,000 members rejected these incentives and went underground.[12]

Guerrilla war

The MNLA commonly employed guerrilla tactics, sabotaging installations, attacking rubber plantations and destroying transportation and infrastructure.[13]

Support for the MNLA was mainly based on around 500,000 of the 3.12 million ethnic Chinese then living in Malaya. These 500,000 have been referred to as 'squatters' and the majority of them were farmers living on the edge of the jungles where the MNLA were based. This allowed the MNLA to supply themselves with food, in particular, as well as providing a source of new recruits.[14] The ethnic Malay population supported them in smaller numbers. The MNLA gained the support of the Chinese because they were denied the equal right to vote in elections, had no land rights to speak of, and were usually very poor. The MNLA's supply organisation was called "Min Yuen." It had a network of contacts within the general population. Besides supplying material, especially food, it was also important to the MNLA as an information gatherer.

The MNLA's camps and hideouts were in the rather inaccessible tropical jungle with limited infrastructure. Most MNLA guerrillas were ethnic Chinese, though there were some Malays, Indonesians and Indians among its members. The MNLA was organised into regiments, although these had no fixed establishments and each encompassed all forces operating in a particular region. The regiments had political sections, commissars, instructors and secret service. In the camps, the soldiers attended lectures on Marxism–Leninism, and produced political newsletters to be distributed to the locals. The MNLA also stipulated that their soldiers needed official permission for any romantic involvement with local women.

In the early stages of the conflict, the guerrillas envisaged establishing "liberated areas" from which the government forces had been driven, with MNLA control being established, but did not succeed at this.

British response

The initial government strategy was primarily to guard important economic targets, such as mines and plantation estates. Later, General Sir Harold Briggs, the British Army's Director of Operations in Malaya, developed an overall strategy known as the Briggs Plan. Its central tenet was that the best way to defeat an insurgency, such as the government was facing, was to cut the insurgents off from their supporters amongst the population. The Briggs plan also recognised the inhospitable nature of the Malayan jungle. A major part of the strategy involved targeting the MNLA food supply, which Briggs recognised came from three main sources: camps within the Malayan jungle where land was cleared to provide food, aboriginal jungle dwellers who could supply the MNLA with food gathered within the jungle and the MNLA supporters within the 'squatter' communities which lived on the edge of the jungle.[14]

The Briggs Plan was multifaceted, with one aspect which has become particularly well known: the forced relocation of some 500,000 rural Malayans, including 400,000 Chinese, from squatter communities on the fringes of the forests into guarded camps called New Villages. These villages were newly constructed in most cases, and were surrounded by barbed wire, police posts and floodlit areas, meant to keep the inhabitants in and the guerrillas out. At the start of the Emergency, the British had 13 infantry battalions in Malaya, including seven partly formed Gurkha battalions, three British battalions, two battalions of the Royal Malay Regiment and a British Royal Artillery Regiment being used as infantry.[15] This force was too small to meet the threat of the "communist terrorists" or "bandits" effectively, and more infantry battalions were needed in Malaya. The British brought in soldiers from units such as the Royal Marines and King's African Rifles. Another effort was a re-formation of the Special Air Service in 1950 as a specialised reconnaissance, raiding and counter-insurgency unit.

The Permanent Secretary of Defence for Malaya, Sir Robert Grainger Ker Thompson, had served in the Chindits in Burma during World War II. His vast experience in jungle warfare proved valuable during this period as he was able to build effective civil-military relations and was one of the chief architects of the counter-insurgency plan in Malaya.[16][17]

Sir Gerald Templer became the commander of the British forces in 1952. He is widely credited with turning the situation in the Malayan emergency in favour of the British forces. During his two-year command 'two-thirds of the guerrillas were wiped out, the incident rate fell from 500 to less than 100 per month and the civilian and security force casualties from 200 to less than 40.'[18] Orthodox historiography suggests that Templer changed the situation in the emergency and his actions and policies were a major part of British success under his command. Revisionist historians have challenged this view and frequently support the ideas of Victor Purcell, a Chinese scholar who as early as 1954 claimed that Templer merely continued policies begun by his predecessors.[19]

In 1951, some British army units began a "hearts and minds campaign" by giving medical and food aid to Malays and indigenous tribes. At the same time, they put pressure on MNLA by patrolling the jungle. The MNLA guerrillas were driven deeper into the jungle and denied resources. The MRLA extorted food from the Sakai and earned their enmity. Many of the captured guerrillas changed sides. In comparison, the MRLA never released any Britons alive.

In the end, the conflict involved a maximum of 40,000 British and other Commonwealth troops, against a peak of about 7–8,000 communist guerrillas.

Control of anti-guerrilla operations

At all levels of government (national, state, and district levels), the military and civil authority was assumed by a committee of military, police and civilian administration officials. This allowed intelligence from all sources to be rapidly evaluated and disseminated, and also allowed all anti-guerrilla measures to be co-ordinated. Each State War Executive Committee, for example, included the State Chief Minister as chairman, the Chief Police Officer, the senior military commander, state home guard officer, state financial officer, state information officer, executive secretary and up to six selected community leaders. The Police, Military and Home Guard representatives and the Secretary formed the operations sub-committee responsible for day-to-day direction of emergency operations. The operations subcommittees as a whole made joint decisions.[20]

Nature of warfare

The British Army soon realised that clumsy sweeps by large formations were unproductive.[21] Instead, platoons or sections carried out patrols and laid ambushes, based on intelligence (from informers, surrendered MNLA personnel, aerial reconnaissance, etc.). A typical operation was "Nassau", carried out in the Kuala Langat swamp:

After several assassinations, a British battalion was assigned to the area. Food control was achieved through a system of rationing, convoys, gate checks and searches. One company began operations in the swamp, about 21 December 1954. On 9 January 1955, full-scale tactical operations began; artillery, mortars and aircraft began harassing fires in the South Swamp. Originally, the plan was to bomb and shell the swamp day and night so that the terrorists [sic] would be driven out into ambushes; but the terrorists were well prepared to stay indefinitely. Food parties came out occasionally, but the civil population was too afraid to report them.Plans were modified; harassing fires were reduced to night-time only. Ambushes continued and patrolling inside the swamp was intensified. Operations of this nature continued for three months without results. Finally on 21 March, an ambush party, after forty-five hours of waiting, succeeded in killing two of eight terrorists. The first two red pins, signifying kills, appeared on the operations map, and local morale rose a little.

Another month passed before it was learned that the terrorists were making a contact inside the swamp. One platoon established an ambush; one terrorist appeared and was killed. May passed without a contact. In June, a chance meeting by a patrol accounted for one killed and one captured. A few days later, after four fruitless days of patrolling, one platoon en route to camp accounted for two more terrorists. The No. 3 terrorist in the area surrendered and stated that food control was so effective that one terrorist had been murdered in a quarrel over food.

On 7 July, two additional companies were assigned to the area; patrolling and harassing fires were intensified. Three terrorists surrendered and one of them led a platoon patrol to the terrorist leader's camp. The patrol attacked the camp, killing four, including the leader. Other patrols accounted for four more; by the end of July, twenty-three terrorists remained in the swamp with no food or communications with the outside world...

This was the nature of operations: 60,000 artillery shells, 30,000 rounds of mortar ammunition, and 2,000 aircraft bombs for 35 terrorists killed or captured. Each one represented 1,500 man-days of patrolling or waiting in ambushes. "Nassau" was considered a success for the end of the emergency was one step nearer.[22]

The Malayan Emergency also marked the first time herbicidal warfare was used. Defoliation experiments using 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T (Agent Orange) were conducted by the British during the conflict in the 1950s. Areas of jungle close to roadways were cleared using chemical defoliation to help prevent ambushes by Communist guerrillas.[23]

Resolution

On 6 October 1951 the MNLA ambushed and killed the British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney. The killing has been described as a major factor in causing the Malayan population to roundly reject the MNLA campaign, and also as leading to widespread fear due to the perception that "if even the High Commissioner was no longer safe, there was little hope of protection and safety for the man-in-the-street in Malaya."[24] More recently, MNLA leader Chin Peng stated that the killing had little effect, and that the communists anyway radically altered their strategy that month in their "October Resolutions".[25] The October Resolutions, a response to the Briggs Plan, involved a change of tactics by reducing attacks on economic targets and civilians, increasing efforts to go into political organisation and subversion, and bolstering the supply network from the Min Yuen as well as jungle farming.

Gurney's successor, Lieutenant General Gerald Templer, was instructed by the British government to push for immediate measures to give Chinese ethnic residents the right to vote. He also pursued the Briggs Plan, and sped up the formation of a Malayan army. At the same time he made it clear that the Emergency itself was the main impediment to accelerating decolonisation. He also increased financial rewards for detecting guerrillas by any civilians and expanded the intelligence network (Special Branch).

Government's declaration of amnesty

On 8 September 1955, the Government of the Federation of Malaya issued a declaration of amnesty to the communists.[26] The Government of Singapore issued an identical offer at the same time. Tunku Abdul Rahman, as Chief Minister, made good the offer of an amnesty but promised there would be no negotiations with the MNLA. The terms of the amnesty were:

- Those of you who come in and surrender will not be prosecuted for any offence connected with the Emergency, which you have committed under Communist direction, either before this date or in ignorance of this declaration.

- You may surrender now and to whom you like including to members of the public.

- There will be no general "ceasefire" but the security forces will be on alert to help those who wish to accept this offer and for this purpose local "ceasefire" will be arranged.

- The Government will conduct investigations on those who surrender. Those who show that they are genuinely intent to be loyal to the Government of Malaya and to give up their Communist activities will be helped to regain their normal position in society and be reunited with their families. As regards the remainder, restrictions will have to be placed on their liberty but if any of them wish to go to China, their request will be given due consideration.[27]

Following the declaration, an intensive publicity campaign on an unprecedented scale was launched by the government. Alliance Ministers in the Federal Government travelled extensively up and down the country exhorting the people to call upon the communists to lay down their arms and take advantage of the amnesty. Public demonstrations and processions in support of the amnesty were held in towns and villages. Despite the campaign, few Communists surrendered to the authorities. It was evident that the communists, having had ample warning of its declaration, conducted intensive anti-amnesty propaganda in their ranks and among the mass organisations, tightened discipline and warned that defection would be severely punished. Some critics in the political circles commented that the amnesty was too restrictive and little more than a restatement of the surrender terms which had been in force for a long period. The critics advocated a more realistic and liberal approach of direct negotiations with the MCP to work out a settlement of the issue. Leading officials of the Labour Party had, as part of the settlement, not excluded the possibility of recognition of the MCP as a political organisation. Within the Alliance itself, influential elements in both the MCA and UMNO were endeavouring to persuade the Chief Minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, to hold negotiations with the MCP.[27]

Baling talks and their consequences

Realising that his conflict had not come to any fruition, Chin Peng sought a discussion with the ruling British government alongside many Malayan officials in 1955. The talks took place in the Government English School at Baling on 28 December. The MCP was represented by Chin Peng, the Secretary-General, Rashid Maidin and Chen Tien, head of the MCP's Central Propaganda Department; on the other side were three elected national representatives, Tunku Abdul Rahman, Dato' Tan Cheng-Lock and David Saul Marshall, the Chief Minister of Singapore. The meeting was intended to pursue a mutual end to the conflict but the Malayan government representatives, led by Tunku Abdul Rahman, dismissed all of Chin Peng's demands. As a result, the conflict heightened and, in response, New Zealand sent NZSAS soldiers, No. 14 Squadron RNZAF, No. 41 (Bristol Freighter) Squadron RNZAF and, later, No. 75 Squadron RNZAF; other Commonwealth members also sent troops to aid the British.

Following the failure of the talks, Tunku decided to withdraw the amnesty on 8 February 1956, five months after it had been offered, stating that he would not be willing to meet the Communists again unless they indicated beforehand their desire to see him with a view to making "a complete surrender".[28] Despite the failure of the talks, the MCP made every effort to resume peace talks with Malayan government, without success. Meanwhile, discussions began in the new Emergency Operations Council to intensify the "People's War" against the guerillas. In July 1957, a few weeks before independence, the MCP made another attempt at peace talks, suggesting the following conditions for a negotiated peace:

- its members should be given privileges enjoyed by citizens; and

- a guarantee that political as well as armed members of the MCP would not be punished.

Tunku Abdul Rahman, however, did not respond to the MCP's proposals. With the independence of Malaya under Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman on 31 August 1957, the insurrection lost its rationale as a war of colonial liberation. The last serious resistance from MRLA guerrillas ended with a surrender in the Telok Anson marsh area in 1958. The remaining MRLA forces fled to the Thai border and further east. On 31 July 1960 the Malayan government declared the state of emergency was over, and Chin Peng left south Thailand for Beijing where he was accommodated by the Chinese authorities in the International Liaison Bureau, where many other Southeast Asian Communist Party leaders were housed.

Australian contribution

Australia was willing to send troops to help a SEATO ally and the first Australian ground forces, the 2nd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (2 RAR), arrived in 1955.[6] The battalion was later be replaced by 3 RAR, which in turn was replaced by 1 RAR. The Royal Australian Air Force contributed No. 1 Squadron (Avro Lincoln bombers) and No. 38 Squadron (C-47 transports), operating out of Singapore, early in the conflict. In 1955, the RAAF extended Butterworth air base, from which Canberra bombers of No. 2 Squadron (replacing No. 1 Squadron) and CAC Sabres of No. 78 Wing carried out ground attack missions against the guerillas. The Royal Australian Navy destroyers Warramunga and Arunta joined the force in June 1955. Between 1956 and 1960, the aircraft carriers Melbourne and Sydney and destroyers Anzac, Quadrant, Queenborough, Quiberon, Quickmatch, Tobruk, Vampire, Vendetta and Voyager were attached to the Commonwealth Strategic Reserve forces for three to nine months at a time. Several of the destroyers fired on Communist positions in Johor State.

Rhodesian contribution

_SAS%2C_1953.jpg)

Southern Rhodesia and its successor, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, contributed two units to Malaya. Between 1951 and 1953, white Southern Rhodesian volunteers formed "C" Squadron of the Special Air Service.[29] The Rhodesian African Rifles, comprising black soldiers and warrant officers, led by white officers, served in Johore state for two years from 1956.[30]

Fijian contribution

During the four years of Fijian involvement, from 1952 to 1956, some 1,600 Fijian troops served. The first to arrive were the 1st Battalion, Fiji Infantry Regiment. Twenty-five Fijian troops died in combat in Malaya.[31] Friendships on and off the battlefield developed between the two nations; the first Prime Minister of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman, became a friend and mentor to Ratu Sir Edward Cakobau, who was a commander of the Fijian Battalion, and who later went on to become the Deputy PM of Fiji and whose son Brigadier General Ratu Epeli is the current President of Fiji.[32] The experience was captured in the documentary, Back to Batu Pahat.[33]

Casualties

During the conflict, security forces killed 6,710 MRLA guerrillas and captured 1,287, while 2,702 guerrillas surrendered during the conflict, and approximately 500 more did so at its conclusion. 1,345 Malayan troops and police were killed during the fighting,[34] as well as 519 Commonwealth personnel. 2,478 civilians were killed, with another 810 recorded as missing.

War crimes

War crimes have been broadly defined by the Nuremberg Principles as "violations of the laws or customs of war," which includes massacres, bombings of civilian targets, terrorism, mutilation, torture, and the murder of detainees and prisoners of war. Additional common crimes include theft, arson, and the destruction of property not warranted by military necessity.[35]

During the Malayan conflict, there were instances where British troops detained and tortured villagers who were suspected in aiding the insurgents while attempting to search for them. Brian Lapping said that there was "some vicious conduct by the British forces, who routinely beat up Chinese squatters when they refused, or possibly were unable, to give information" about the insurgents. There were also cases of the bodies of dead guerrillas being exhibited in public. The Scotsman newspaper lauded these tactics as a good practice since "simple-minded peasants are told and come to believe that the communist leaders are invulnerable". British forces also booby-trapped jungle food stores, burned villages and secretly supplied self-detonating grenades and bullets to the insurgents to instantly kill the user. Some civilians and detainees were also shot, either because they attempted to flee from them on the grounds that they could give the insurgents valuable assistance to continue to fight against British forces or simply because they refused to give intelligence to British forces. These tactics created strained relations between civilians and British forces in Malaya as they were counterproductive in generating the one resource critical in a counterinsurgency, good intelligence.[36] British troops were often unable to tell the difference between enemy combatants and non-combatant civilians while conducting military operations through the jungles, due to the fact the guerrillas wore civilian clothing and had support from the sympathetic civilian populations.

In the "Batang Kali massacre", 24 villagers were killed by 7th Platoon, G Company, 2nd Scots Guards, after they surrounded a rubber plantation at Sungai Rimoh near Batang Kali in Selangor in December 1948. The only survivor of the killings was a man named Chong Hong who was in his 20s at the time. He fainted and was presumed dead.[37][38][39][40]

Decapitation and mutilation of insurgents by British forces were also common as a way to identify dead guerrillas when it was not possible to bring their corpses in from the jungle. A photograph of a Royal Marine commando holding two insurgents' heads caused a public outcry in April 1952. The Colonial Office privately noted that "there is no doubt that under international law a similar case in wartime would be a war crime".[36][41][42]

As part of the Briggs' Plan devised by British General Sir Harold Briggs, 500,000 people (roughly ten percent of Malaya's population) were eventually removed from the land. Tens of thousands of homes were destroyed, and many people were interned in guarded camps called "New Villages". The intent of this measure was to inflict collective punishments on villages where people were deemed to be aiding the insurgents and to isolate civilians from guerrilla activity. While considered necessary, some of the cases involving the widespread destruction went beyond justification of military necessity. This practice was prohibited by the Geneva Conventions and customary international law which stated that the destruction of property must not happen unless rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.[36][41][43]

Comparisons with Vietnam

Differences

The conflicts in Malaya and Vietnam have been compared many times and it has been asked by historians how a British force of 35,000 succeeded where over half a million U.S. soldiers failed in a smaller area. The two conflicts differ in several key points.

- Whereas the MNLA never numbered more than about 8,000 insurgents, the Peoples' Army of (North) Vietnam fielded over a quarter-million soldiers, in addition to roughly 100,000 National Liberation Front (or Vietcong) guerillas.

- The combined support of the Soviet Union, North Korea,[44] Cuba[45] and the People's Republic of China (PRC) provided large amounts of the latest military hardware, logistical support, personnel and training to North Vietnam.

- North Vietnam's shared border with its ally China (PRC) allowed for continuous assistance and resupply.

- Britain never approached the Emergency as a conventional conflict and quickly implemented an effective combined intelligence (led by Malayan Police Special Branch against the political arm of the guerrilla movement)[46][47] and a "hearts and minds" operation.

- Most of the insurgents were ethnically Chinese, who were seen as foreigners and resented by many indigenous Malays who preferred the British.

- Many Malayans had fought side by side with the British against the Japanese occupation in World War II, including Chin Peng. This is in contrast to Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) where French colonial officials had not been at war against the Japanese, who endeavoured to excite Vietnamese nationalism against France. This factor of trust between the locals and the colonials was what gave the British an advantage over the French and later, the Americans in Vietnam, neither of whom enjoyed such trust from the Vietnamese.

- In purely military terms, the British Army recognised that in a low-intensity war, the individual soldier's skill and endurance was of far greater importance than overwhelming firepower (artillery, air support, etc.) Even though many British soldiers were conscripted National Servicemen, the necessary skills and attitudes were taught at a Jungle Warfare School, which also worked out the optimum tactics based on experience gained in the field.[48]

- In Vietnam, soldiers and supplies passed through external countries such as Laos and Cambodia where US forces were not legally permitted to enter. This allowed Vietnamese Communist troops safe haven from US ground attacks. The MNLA had only a border with Thailand, where they were forced to take shelter near the end of the conflict.

Similarities

Many tactics employed by the British in Malaya were similar to the ones the US used during the Vietnam War. The following examples are listed below.

Agent Orange

During the Malayan Emergency, Britain was the first nation to employ the use of herbicides and defoliants to destroy bushes, food crops, and trees to deprive the insurgents of cover and as part of the food denial campaign in the early 1950s. The 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D (Agent Orange) were used to clear lines of communication and wipe out food crops as part of this strategy and in 1952, trioxone, and mixtures of the aforementioned herbicides, were sent along a number of key roads. From June to October 1952, 1,250 acres of roadside vegetation at possible ambush points were sprayed with defoliant, described as a policy of “national importance”. The British reported that the use of herbicides and defoliants could be effectively replaced by removing vegetation by hand and the spraying was stopped. However, after this strategy failed, the use of herbicides and defoliants in effort to fight the insurgents was restarted under the command of British General Sir Gerald Templer in February 1953, as a means of destroying food crops grown by communist forces in jungle clearings. Helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft despatched STCA and Trioxaone, along with pellets of chlorophenyl N,N-Dimethyl-1-naphthylamine onto crops such as sweet potatoes and maize. Many Commonwealth personnel who handled and/or used Agent Orange during, and in the decades after, the conflict suffered from serious exposure to dioxin and Agent Orange, which also caused major soil erosion to areas of Malaya. An estimated 10,000 civilians and insurgents in Malaya also suffered heavily from the effects of the defoliant (though many historians agree it was likely more than this number given that Agent Orange was used on a large scale in the Malayan conflict and unlike the US, the British government manipulated the numbers and kept its secret very tight in fear of negative world public opinion).[49][50][51]

After the Malayan conflict ended in 1960, the US considered British precedent in deciding that the use of defoliants was a legally accepted tactic of warfare. Secretary of State Dean Rusk advised President John F. Kennedy that herbicide became precedent for warfare had been established by the British in Malaya in their use of aircraft for destroying crops and trees by herbicide spraying.[23][43]

Aerial bombardment

Like the US Air Force in Vietnam, widespread saturation bombardment was used by the Royal Air Force throughout the conflict in Malaya. Britain conducted 4,500 air strikes in the first five years of the Malayan war. Mapping was poor, communications were abysmal, the meteorology was unfavourable and airfields were few. Buzzing likely enemy positions was used (the modern 'show of force'), and the bombing of potential escape routes was also occasionally practised. Author Robert Jackson said that: "During 1956, some 545,000 lb. of bombs had been dropped on a supposed [guerrilla] encampment...but a lack of accurate pinpoints had nullified the effect. The camp was again attacked at the beginning of May 1957...[dropping] a total of 94,000 lb. of bombs, but because of inaccurate target information this weight of explosive was 250 yards off target. Then, on 15 May...70,000 lb. of bombs were dropped". "The attack was entirely successful", Jackson declares, since "four terrorists were killed". The author also notes that a 500 lb. nose-fused bomb was employed from August 1948 and had a mean area of effectiveness of 15,000 square feet. "Another very viable weapon" was the 20 lb. fragmentation bomb, a forerunner of cluster bombs. "Since a Sunderland could carry a load of 190, its effect on terrorist morale was considerable", Jackson states. "Unfortunately, it was not used in great numbers, despite its excellent potential as a harassing weapon". On one occasion a Lincoln bomber "dropp[ed] its bombs 600 yards short...killing twelve civilians and injuring twenty-six others". The British reported that bombing jungles was largely a waste of effort due to inaccurate targeting and the inability to confirm if a target was hostile or not. Throughout the 12-year conflict, between 670 to 995 non-combatants were killed by British RAF bombers.[36][42][52]

Resettlement program

Britain also set up a “resettlement” programme that provided a model for the US’s Strategic Hamlet Program in Vietnam. During the Malayan Emergency, 450 new settlements were created and it is estimated that 470,509 people – 400,000 Chinese – were interned in the resettlement program. A key British war measure was inflicting collective punishments on villages where people were deemed to be aiding the insurgents. At Tanjong Malim in March 1952 Templer imposed a twenty-two-hour house curfew, banned everyone from leaving the village, closed the schools, stopped bus services and reduced the rice rations for 20,000 people. The latter measure prompted the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to write to the Colonial Office noting that the “chronically undernourished Malayan” might not be able to survive as a result. “This measure is bound to result in an increase, not only of sickness but also of deaths, particularly amongst the mothers and very young children”. Some people were fined for leaving their homes to use outside latrines. In another collective punishment – at Sengei Pelek the following month – measures included a house curfew, a reduction of 40 per cent in the rice ration and the construction of a chain-link fence 22 yards outside the existing barbed wire fence around the town. Officials explained that these measures were being imposed upon the 4,000 villagers “for their continually supplying food” to the insurgents and “because they did not give information to the authorities”.[53]

Search and destroy

Like the US in Vietnam, it was also common among British troops to set fire to villages whose inhabitants were accused of supporting the insurgents, detaining thousands of suspected collaborators, and to deny the insurgents cover. British units that discovered civilians providing assistance to insurgents were to detain and interrogate them, using torture and threat of violence upon family, to discover the location of insurgent camps. Insurgents had numerous advantages over British forces; they lived in closer proximity to villagers, they sometimes had relatives or close friends in the village, and they were not afraid to threaten violence or torture and murder village leaders as an example to the others, forcing them to assist them with food and information. British forces thus faced a dual threat: the insurgents and the silent network in villages who supported them. While the insurgents rarely sought out contact with British forces, they did use terrorist tactics to intimidate civilians and elicit material support. British troops often described the terror of jungle patrols; in addition to watching out for insurgent fighters, they had to navigate difficult terrain and avoid dangerous animals and insects. Many patrols would stay in the jungle for days, even weeks, without encountering the enemy and then, in a brief moment, insurgents would ambush them. British forces, unable to distinguish from friend to foe, had to adjust to the constant risk of an insurgent attack. These instances led to the infamous incident at Batang Kali where 24 unarmed villagers were killed by British troops.[36][41]

Legacy

The Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation of 1963–66 arose from tensions between Indonesia and the new British backed Federation of Malaysia which was conceived in the aftermath of the Malayan Emergency.

In the late 1960s, the coverage of the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War prompted the initiation of investigations in the UK concerning alleged war crimes perpetrated by British forces during the Emergency, such as the Batang Kali massacre. No charges have yet been brought against the British forces involved and claims have been repeatedly dismissed as propaganda by the British government despite evidence suggestive of a cover-up.[54]

In popular culture

In popular Malaysian culture, the Emergency has frequently been portrayed as a primarily Malay struggle against the communists. This perception has been criticised by some, such as Information Minister Zainuddin Maidin, for not recognising Chinese and Indian efforts.[55] This portrayal also obscures the reality that the Malayan Communist Party led the fighting for independence against British and Commonwealth.

The British film industry made a number of films with the background of the Emergency including:

- The Planter's Wife (1952)

- Windom's Way (1957)

- The 7th Dawn (1964)

- The Virgin Soldiers (1969)

- Stand Up, Virgin Soldiers (1977)

See also

- British military history

- British Far East Command

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office migrated archives

- History of Malaysia

Notes

- ↑ Geoffrey Jukes (1 January 1973). The Soviet Union in Asia. University of California Press. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-0-520-02393-2.

- ↑ Mohamed Amin and Malcolm Caldwell (eds.), The Making of a Neo Colony, (1977), Spokesman Books, UK, footnote, p. 216.

- ↑ Peng, Chin, My Side of History, Media Masters, 2003, p10

- 1 2 Wendy Khadijah Moore, Malaysia a Pictorial History 1400–2004, ed. Dianne Buerger and Sharon Ham (n.p.: Archipelago Press, 2004), page 194

- ↑ "Tin Mining". GWN Mining. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Malayan Emergency, 1950–60". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Moody, Steve Moody. "Japanese Rice Trade Policy". Japan-101. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ↑ Wong, Heng (31 August 1999). "Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA)". National Library Board, Singapore. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- 1 2 Eric Stahl, "Doomed from the Start: A New Perspective on the Malayan Insurgency" (master's thesis, 2003)

- ↑ Andaya, Barbara Watson; Leonard Y. Andaya (2001). A History of Malaysia. Palgrave. p. 271.

- ↑ Jackson, Robert (2008). The Malayan Emergency. London. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Jackson, Robert (2008). The Malayan Emergency. London: Pen & Sword Aviation. p. 10.

- ↑ Rashid, Rehman (1993). A Malaysian Journey. p. 27. ISBN 983-99819-1-9.

- 1 2 O. Tilman, Robert (1966). "The non-lessons of the Malayan emergency". Asian Survey 6 (8): 407–419. doi:10.1525/as.1966.6.8.01p01954.

- ↑ Karl Hack, Defense & Decolonization in South-East Asia, p. 113.

- ↑ Joel E. Hamby Civil-military operations: joint doctrine and the Malayan Emergency, Joint Force Quarterly, Autumn, 2002, Paragraph 3,4

- ↑ Peoples, Curtis. "The Use of the British Village Resettlement Model in Malaya and Vietnam, 4th Triennial Symposium (April 11–13, 2002), The Vietnam Center and Archive, Texas Tech University".

- ↑ Clutterbuck, Richard (1985). Conflict and violence in Singapore and Malaysia 1945–83. Singapore: Graham Brash.

- ↑ Ramakrishna, Kumar (February 2001). "'Transmogrifying' Malaya: The Impact of Sir Gerald Templer (1952–54)". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies (Cambridge University Press) 32 (1): 79–92. doi:10.1017/S0022463401000030. JSTOR 20072300.

- ↑ Conduct of Anti-Terrorist Operations in Malaya, Director of Operations, Malaya, 1958, Chapter III: Own Forces

- ↑ Nagl (2002), pp.67–70

- ↑ Taber, The War of the Flea, pp.140–141. Quote from Marine Corps Schools, "Small Unit Operations" in The Guerrilla – and how to Fight Him

- 1 2 Bruce Cumings (1998). The Global Politics of Pesticides: Forging Consensus from Conflicting Interests. Earthscan. p. 61.

- ↑ Ongkili, James P. (1985). Nation-building in Malaysia 1946–1974. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 0-19-582681-7.

- ↑ Chin, C. C. Chin; Hack, Karl (2004). Dialogues with Chin Peng: New Light on the Malayan Communist Party. NUS Press.

- ↑ Memorandum from the Chief Minister and Minister for Internal and Security, No. 386/17/56, 30 April 1956. CO1030/30

- 1 2 Prof Madya Dr. Nik Anuar Nik Mahmud, Tunku Abdul Rahman and His Role in the Baling Talks

- ↑ MacGillivray to the Secretary of State for the Colonies, 15 March 1956, CO1030/22

- ↑ Binda, Alexandre (November 2007). Heppenstall, David, ed. Masodja: The History of the Rhodesian African Rifles and its forerunner the Rhodesian Native Regiment. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. p. 127. ISBN 978-1920143039.; Shortt, James; McBride, Angus (1981). The Special Air Service. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0-85045-396-8.

- ↑ Binda, Alexandre (November 2007). Heppenstall, David, ed. Masodja: The History of the Rhodesian African Rifles and its forerunner the Rhodesian Native Regiment. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-1920143039.

- ↑ "Documentary to Explore the Relationship Between Malaysia and Fiji During the Malayan Emergency". Fiji Government Online Portal. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ "Archive – Online edition of the newspaper. Includes national and regional news, headlines, sports, and editorial column.". Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ "YouTube". Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ↑ "Royal Malaysian Police (Malaysia)". Crwflags.com. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ↑ Gary D. Solis (15 February 2010). The Law of Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law in War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 301–303. ISBN 978-1-139-48711-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Other Forgotten War: Understanding Atrocities During the Malayan Emergency

- ↑ "New documents reveal cover-up of 1948 British 'massacre' of villagers in Malaya". The Guardian. 9 April 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ "Batang Kali massacre families snubbed". The Sun Daily. 29 October 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ "UK urged to accept responsibility for 1948 Batang Kali massacre in Malaya". The Guardian. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ "Malaysian lose fight for 1948 'massacre' inquiry". BBC News. 4 September 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 Fujio Hara (December 2002). Malaysian Chinese & China: Conversion in Identity Consciousness, 1945–1957. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 61–65.

- 1 2 Mark Curtis (15 August 1995). The Ambiguities of Power: British Foreign Policy Since 1945. pp. 61–71.

- 1 2 Pamela Sodhy (1991). The US-Malaysian Nexus: Themes in Superpower-Small State Relations. Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia. pp. 284–290.

- ↑ Gluck, Caroline. "N Korea admits Vietnam war role". BBC News. Retrieved 7 July 2001.

- ↑ Bourne, Peter G. Fidel: A Biography of Fidel Castro (1986) p. 255; Coltman, Leycester The Real Fidel Castro (2003) p. 211

- ↑ Comber (2006), Malaya's Secret Police 1945–60. The Role of the Special Branch in the Malayan Emergency

- ↑ Clutterbuck, Richard (1967). The long long war: The emergency in Malaya, 1948–1960. Cassell. Cited at length in Vietnam War essay on Insurgency and Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya, eHistory, Ohio State University.

- ↑ "Analysis of British tactics in Malaya" (PDF).

- ↑ Pesticide Dilemma in the Third World: A Case Study of Malaysia. Phoenix Press. 1984. p. 23.

- ↑ Arnold Schecter, Thomas A. Gasiewicz (4 July 2003). Dioxins and Health. pp. 145–160.

- ↑ Albert J. Mauroni (July 2003). Chemical and Biological Warfare: A Reference Handbook. pp. 178–180.

- ↑ Robert Jackson (August 2008). The Malayan Emergency. pp. 28–34.

- ↑ Pamela Sodhy (1991). The US-Malaysian nexus: Themes in superpower-small state relations. Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia. pp. 356–365.

- ↑ Townsend, Mark (9 April 2011). "New documents reveal cover-up of 1948 British 'massacre' of villagers in Malaya". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Kaur, Manjit (16 December 2006). Zam: Chinese too fought against communists. The Star.

Further reading

- Barber, Noel (1971). War of The Running Dogs. London: Collins. ISBN 0-00-211932-3.

- Comber, Leon (2003). "The Malayan Security Service (1945–1948)". Intelligence and National Security, 18:3. pp. 128–153.

- Comber, Leon (February 2006). "The Malayan Special Branch on the Malayan-Thai Frontier during the Malayan Emergency". Intelligence and National Security, 21:1. pp. 77–99.

- Comber, Leon (2006). "Malaya's Secret Police 1945–60. The Role of the Special Branch in the Malayan Emergency". PhD dissertation, Monash University. Melbourne: ISEAS (Institute of SE Asian Affairs, Singapore) and MAI (Monash Asia Institute).

- Hack, Karl (1999). "Corpses, Prisoners of War and Captured documents: British and Communist Narratives of the Malayan Emergency, and the Dynamics of Intelligence Transformation". Intelligence and National Security.

- Jumper, Roy (2001). Death Waits in the Dark: The Senoi Praaq, Malaysia's Killer Elite. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31515-9.

- Nagl, John A. (2002). Learning to Eat Soup With a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam. University of Chicago. ISBN 0-226-56770-2.

- Short, Anthony (1975). The Communist Insurrection in Malaya 1948–1960. London and New York: Frederick Muller. Reprinted (2000) as In Pursuit of Mountain Rats. Singapore.

- Stubbs, Richard (2004). Hearts and Minds in Guerilla Warfare: The Malayan Emergency 1948–1960. Eastern University. ISBN 981-210-352-X.

- Taber, Robert (2002). War of the flea: the classic study of guerrilla warfare. Brassey's. ISBN 978-1-57488-555-2.

External links

| Library resources about Malayan Emergency |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malayan Emergency. |

- Australian War Memorial (Malayan Emergency 1950–1960)

- Far East Strategic Reserve Navy Association (Australia) Inc. (Origins of the FESR – Navy)

- Malayan Emergency (AUS/NZ Overview)

- Britain's Small Wars (Malayan Emergency)

- PsyWar.Org (Psychological Operations during the Malayan Emergency)

- www.roll-of-honour.com (Searchable database of Commonwealth Soldiers who died)

- A personal account of flying the Bristol Brigand aircraft with 84 Squadron RAF during the Malayan Emergency - Terry Stringer

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||