Malayan Campaign

| ||||||

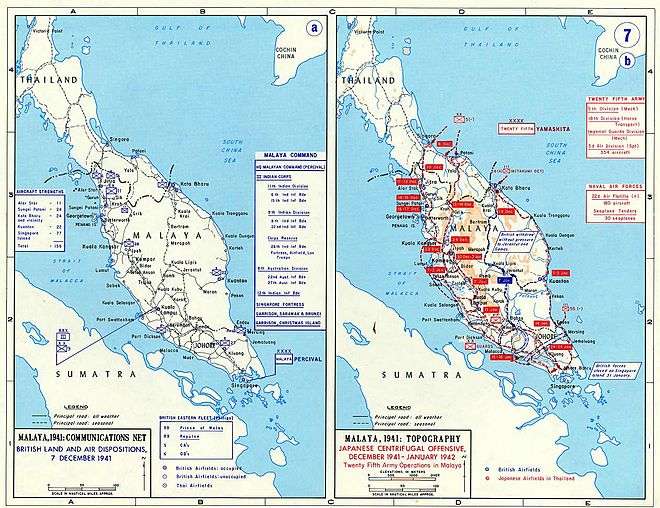

The Malayan Campaign was fought by Allied and Axis forces in Malaya, from 8 December 1941 – 31 January 1942 during the Second World War. It was dominated by land battles between British Commonwealth army units, and the Imperial Japanese Army with minor skirmishes at the beginning of the campaign between British Commonwealth and Royal Thai Armed Forces. For the British, Indian, Australian and Malayan forces defending the colony, the campaign was a total disaster.

The operation is notable for the Japanese use of bicycle infantry, which allowed troops to carry more equipment and swiftly move through thick jungle terrain. Royal Engineers, equipped with demolition charges, destroyed over a hundred bridges during the retreat, yet this did little to delay the Japanese. By the time the Japanese had captured Singapore, they had suffered 9,600 casualties.[6]

Background

Japanese

By 1941 the Japanese had been engaged for four years in trying to subjugate China. They were heavily reliant on imported materials for their military forces, particularly oil from the United States.[7] From 1940 to 1941, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands imposed embargoes on supplying oil and war materials to Japan.[7] The object of the embargoes was to assist the Chinese and encourage the Japanese to halt military action in China. The Japanese considered that pulling out of China would result in a loss of face and decided instead to take military action against US, British and Dutch territories in South East Asia.[7] The Japanese forces for the invasion were assembled in 1941 on Hainan Island and in French Indochina. This troop build-up was noticed by the Allies and, when asked, the Japanese advised that it related to its operations in China.

When the Japanese invaded, they had over 200 tanks, consisting of the Type 95 Ha-Go, Type 97 Chi-Ha, Type 89 I-Go and Type 97 Te-Ke.[8] In addition, they had over 500 combat aircraft available. Commonwealth troops were equipped with the Lanchester 6x4 Armoured Car, Marmon-Herrington Armoured Car, Universal Carrier and only 23 obsolete light tanks, none of which were sufficiently armed for armoured warfare.[3] They had just over 250 combat aircraft, but half of these were destroyed inside the first few days of combat.

Commonwealth

Between the wars, the United Kingdom's military strategy in the Far East was undermined by a lack of attention and funding. In 1937, Major-General William Dobbie, Officer Commanding Malaya (1935–1939), looked at Malaya's defences and reported that during the monsoon season, from October to March, landings could be made by an enemy on the east coast and bases could be established in Siam (Thailand). He predicted that landings could be made at Songkhla and Pattani in Siam, and Kota Bharu in Malaya. He recommended large reinforcements to be sent immediately. His predictions turned out to be correct, but his recommendations were ignored. The British government's plans relied primarily on the stationing of a strong fleet at the Singapore Naval Base in the event of any enemy hostility, in order to defend both Britain's Far Eastern possessions and the route to Australia. A strong naval presence was also thought to act as a deterrent against possible aggressors.

By 1940, however, the army commander in Malaya, Lieutenant-General Lionel Bond, conceded that a successful defence of Singapore demanded the defence of the whole peninsula, and that the naval base alone would not be sufficient to deter a Japanese invasion.[9] Military planners concluded that the desired Malayan air force strength would be 300–500 aircraft, but this was never reached because of the higher priorities in the allocation of men and material for Britain and the Middle East.

The defence strategy for Malaya rested on two basic assumptions: first, that there would be sufficient early warning of an attack to allow for reinforcement of British troops, and second, that American help was at hand in case of attack. By late 1941, it became clear that neither of these assumptions had any real substance.[9] In addition, Churchill and Roosevelt had agreed that in the event of war breaking out in the east, priority would be given to finishing the war in the west. The east, until that time, would be a secondary priority. Containment was considered the primary strategy in the east.

Intelligence operations

Planning for this offensive was undertaken by the Japanese Military Affairs Bureau's Unit 82 based in Taiwan. Intelligence on Malaya was gathered through a network of agents which included Japanese embassy staff; disaffected Malayans (particularly members of the Japanese established Tortoise Society); and Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese business people and tourists. Japanese spies, which included a British intelligence officer, Captain Patrick Stanley Vaughan Heenan, also provided intelligence and assistance.

Prior to hostilities Japanese intelligence officers like I Fujiwara had established covert intelligence offices (or Kikans) that linked up with the Malay and Indian pro-independence organisations such as Kesatuan Melayu Muda in Malaya Indian Independence League. The Japanese gave these movements financial support in return for their members providing intelligence and later assistance in determining Allied troop movements, strengths, and dispositions prior to the invasion.

Through these networks and prior to the invasion the Japanese knew where the Commonwealth forces were based and their unit strengths, had good maps of Malaya, and had local guides available to provide them with directions.[10]

November 1941

In November 1941 the British became aware of the large scale buildup of Japanese troops in French Indo-China. Thailand was seen to be under threat from this build-up as well as Malaya. British strategists had foreseen the possibility of Thailand's Kra peninsula being used by the Japanese to invade Malaya. To counteract this potential threat, plans for a pre-emptive invasion of southern Thailand, named Operation Matador, had been drawn up. By the time the invasion became highly likely the British decided not to use them for political reasons.[11]

Japan invades

The Battle of Malaya began when the 25th Army invaded Malaya on 8 December 1941. Japanese troops launched an amphibious assault on the northern coast of Malaya at Kota Bharu and started advancing down the eastern coast of Malaya.[12] This was made in conjunction with landings at Pattani and Songkhla in Thailand, where they then proceeded south overland across the Thailand-Malayan border to attack the western portion of Malaya.[12]

The Japanese were allied with the Axis collaborators, the Vichy French, and had been given access to naval facilities and supplies in French Indochina where they massed their forces for the invasion. They then coerced the Thai government into letting them use Thai military bases to launch attacks into Malaya, after having fought Thai troops for eight hours early in the morning. At 04:00, 17 Imperial Japanese Navy bombers attacked Singapore, the first ever air raid aimed at the colony. It became evident Japanese aircraft bombers operating in Saigon were now in range of Singapore.[12]

The Japanese were initially resisted by III Corps of the Indian Army and several British Army battalions. The Japanese quickly isolated individual Indian units defending the coastline, before concentrating their forces to surround the defenders and forcing their surrender.[12]

The Japanese forces held a slight advantage in numbers on the ground in northern Malaya, and were significantly superior in close air support, armour, co-ordination, tactics and experience, with the Japanese units having fought in China. The Allies had no tanks, which had put them at a severe disadvantage. The Japanese also used bicycle infantry and light tanks, which allowed swift movement of their forces overland through terrain covered with thick tropical rainforest, albeit criss-crossed by native paths. Although the Japanese had not brought bicycles with them (in order to speed the disembarkation process), they knew from their intelligence that suitable machines were plentiful in Malaya and quickly confiscated what they needed from civilians and retailers.[12]

A replacement for Operation Matador, named Operation Krohcol, was implemented on 8 December, but the Indian troops were easily defeated by the Japanese 5th Division, which had already landed in Pattani Province, Thailand.[1]

The naval Force Z—consisting of the battleship HMS Prince of Wales, battlecruiser HMS Repulse, and four destroyers, under the command of Admiral Tom Phillips—had arrived right before the outbreak of hostilities. However, Japanese air superiority led to the sinking of the capital ships on 10 December, leaving the east coast of Malaya exposed and allowing the Japanese to continue their landings.[12]

-

Lt Gen Arthur Percival GOC of Malaya at the time of the Japanese invasion

-

Lt Gen Tomoyuki Yamashita, Commander of the Japanese 25th Army.

-

The Japanese bicycle

Air war

The Allied fighter squadrons in Malaya—equipped with Brewster Buffaloes—were beset with numerous problems, including poorly built and ill-equipped planes;[13][14] inadequate supplies of spare parts;[14] inadequate numbers of support staff;[15] airfields that were difficult to defend against air attack;[13] lack of a clear and coherent command structure;[13] antagonism between RAF and Royal Australian Air Force squadrons and personnel;[15] and inexperienced pilots lacking appropriate training.[13]

Commonwealth fighters were swept from the sky by the Nakajima Ki-43 Oscar of Sentai (groups) 59 and 64, and the Nakajima Ki-27 Nate of other three Sentai. Despite being slower, undergunned, underpowered in comparison (Ki-27's even had fixed main landing gear) as well as having absolutely no protection for pilot, engine or fuel tanks, Japanese fighters managed to get absolute air superiority in Malaya thanks to their superior agility and training. Because of this, allied air forces suffered severe losses in the first week of the campaign, resulting in the ongoing merger of squadrons and their gradual evacuation to the Dutch East Indies. One pilot—Sergeant Malcolm Neville Read of No. 453 Squadron RAAF—sacrificed himself by ramming his Buffalo into a Nakajima Ki-43 Oscar of 64th Sentai over Kuala Lumpur on 22 December.[16][17]

One squadron of the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force (ML-KNIL) — 2-VLG-V — was deployed to Singapore, contributing to the Allied cause before being recalled to Java on 18 January. Several Dutch pilots—including Jacob van Helsdingen and August Deibel—responded to a number of air raids over Singapore while stationed at Kallang Airport. They claimed a total of six aircraft, particularly the Nakajima Ki-27 Nate, which fared poorly in Malaya. Their involvement in Malaya, however, did little to weaken the Japanese air force.

The remaining offensive aircraft—the Bristol Blenheim, Lockheed Hudson light bombers and very specially the Vickers Vildebeest torpedo bombers—were considered obsolete for the European theater of operations. Most were quickly destroyed by Japanese aircraft and played an insignificant part in the campaign. One Blenheim pilot—Squadron Leader Arthur Scarf—was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for an attack on 9 December.[18]

In addition, the Japanese military intelligence service had managed to recruit a British officer, Captain Patrick Heenan, an Air Liaison Officer with the Indian Army.[19] While the effects of Heenan's actions are disputed, the Japanese were able to destroy almost every Allied aircraft in northern Malaya within three days. Heenan was arrested on 10 December and sent to Singapore. However, the Japanese had already achieved air superiority.

Advance down the Malayan Peninsula

The defeat of Allied troops at Jitra by Japanese forces, supported by tanks moving south from Thailand on 11 December 1941 and the rapid advance of the Japanese inland from their Kota Bharu beachhead on the north-east coast of Malaya overwhelmed the northern defences. Without any real naval presence, the British were unable to challenge Japanese naval operations off the Malayan coast, operations which proved invaluable to the invading army. With virtually no remaining Allied planes, the Japanese also had mastery of the skies, leaving the Allied ground troops and civilian population exposed to air attack.[20]

The Malayan island of Penang was bombed daily by the Japanese from 8 December and abandoned on 17 December. Arms, boats, supplies and a working radio station were left in haste to the Japanese. The evacuation of Europeans from Penang, with local inhabitants being left to the mercy of the Japanese, caused much embarrassment for the British and alienated them from the local population. Historians judge that "the moral collapse of British rule in Southeast Asia came not at Singapore, but at Penang".[21]

However many who were present during the evacuation did not experience it as a scramble. It was a response to an order from British High Command which had come to the conclusion that Penang should be abandoned as it had no tactical or strategic value in the rapidly changing military scheme of things at that time.[22]

On 23 December, Major-General David Murray-Lyon of the Indian 11th Infantry Division was removed from command to little effect. By the end of the first week in January, the entire northern region of Malaya had been lost to the Japanese. At the same time, Thailand officially signed a Treaty of Friendship with Imperial Japan, which completed the formation of their loose military alliance. Thailand was then allowed by the Japanese to resume sovereignty over several sultanates in northern Malaya, thus consolidating their occupation. It did not take long for the Japanese army's next objective, the city of Kuala Lumpur, to fall. The Japanese entered and occupied the city unopposed on 11 January 1942. Singapore Island was now less than 200 mi (320 km) away for the invading Japanese army.[23]

The 11th Indian Division managed to delay the Japanese advance at Kampar for a few days, in which the Japanese suffered severe casualties in terrain that did not allow them to use their tanks or their air superiority to defeat the British. The 11th Indian Division was forced to retreat when the Japanese landed troops by sea south of the Kampar position. The British retreated to prepared positions at Slim River.[24]

At the Battle of Slim River, in which two Indian brigades were practically annihilated, the Japanese used surprise and tanks to devastating effect in a risky night attack. The success of this attack forced Percival into replacing the 11th Indian Division with the 8th Australian Division.

Defence of Johor

By mid-January, the Japanese had reached the southern Malayan state of Johore where, on 14 January, they encountered troops from the Australian 8th Division, commanded by Major-General Gordon Bennett, for the first time in the campaign. During engagements with the Australians, the Japanese experienced their first major tactical setback, due to the stubborn resistance put up by the Australians at Gemas. The battle—centred around the Gemencheh Bridge—proved costly for the Japanese, who suffered up to 600 casualties. However, the bridge itself (which had been demolished during the fighting) was repaired within six hours.[25]

As the Japanese attempted to outflank the Australians to the west of Gemas,[26] one of the bloodiest battles of the campaign began on 15 January on the peninsula's West coast near the Muar River. Bennett allocated the 45th Indian Brigade—a new and half-trained formation—to defend the river's South bank but the unit was outflanked by Japanese units landing from the sea and the Brigade was effectively destroyed with its commander, Brigadier H. C. Duncan, and all three of his battalion commanders killed.[25] Two Australian infantry battalions—which had been sent to support the 45th Brigade—were also outflanked and their retreat cut off, with one of the Australian battalion commanders killed in the fighting around the town of Bakri, south-east of Muar. During the fighting at Bakri Australian anti-tank gunners had destroyed nine Japanese tanks,[25] slowing the Japanese advance long enough for the surviving elements of the five battalions to attempt an escape from the Muar area.[25]

Led by Australian Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Anderson, the surviving Indian and Australian troops formed the "Muar Force" and fought a desperate four-day withdrawal,[25] allowing remnants of the Commonwealth troops withdrawing from northern Malaya to avoid being cut off and to push past the Japanese to safety. When the Muar Force reached the bridge at Parit Sulong and found it to be firmly in enemy hands, Anderson, with mounting numbers of dead and wounded, ordered "every man for himself". Those that could took to the jungles, swamps and rubber plantations in search of their division headquarters at Yong Peng. The wounded were left to the mercy of the Japanese and all but two out of 135 were tortured and killed in the Parit Sulong Massacre. Anderson was awarded a Victoria Cross for his fighting withdrawal.[25] The Battle of Muar cost the allies an estimated 3,000 casualties including one brigadier and four battalion commanders.[25]

On 20 January, further Japanese landings took place at Endau, in spite of an air attack by Vildebeest bombers. The final Commonwealth defensive line in Johore of Batu Pahat-Kluang-Mersing was now being attacked along its full length. Unfortunately, Percival had resisted the construction of fixed defences in Johore, as on the North shore of Singapore, dismissing them in the face of repeated requests to start construction from his Chief Engineer, Brigadier Ivan Simson, with the comment "Defences are bad for morale." On 27 January, Percival received permission from the commander of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command, General Archibald Wavell, to order a retreat across the Johore Strait to the island of Singapore.

Retreat to Singapore

On 31 January, the last organised Allied forces left Malaya, and Allied engineers blew a 70 ft (21 m)-wide hole in the causeway that linked Johore and Singapore; a few stragglers would wade across over the next few days. Japanese raiders and infiltrators, often disguised as Singaporean civilians, began to cross the Straits of Johor in inflatable boats soon afterwards.

In less than two months, the Battle for Malaya had ended in comprehensive defeat for the Commonwealth forces and their retreat from the Malay Peninsula to the fortress of Singapore. Nearly 50,000 Commonwealth troops had been captured or killed during the battle. The Japanese Army invaded the island of Singapore on 7 February and completed their conquest of the island on 15 February, capturing 80,000 more prisoners out of the 85,000 allied defenders. The final battle before the surrender was with the Royal Malay Regiment at Bukit Candu on the 14 February.

By the end of January, Patrick Heenan, a British Indian Army captain convicted of spying for Japan, had been court-martialled and sentenced to death.[19] On 13 February, five days after the invasion of Singapore Island, and with Japanese forces approaching the city centre, Heenan was taken by military police to the waterside and was hastily executed. His body was thrown into the sea.

Battles of the campaign

- Battle of Kota Bharu (8 December, 1941)

Three transports landed some 5,200 troops at Koto Bharu (Malaysia's NW corner). The beaches had been prepared with wire and pillboxes, and were defended with artillery and aircraft. One Japanese transport was sunk, with two damaged. But after heavy fighting the Japanese succeeded in landing most of their troops with about 800 casualties. - Bombing of Singapore (December, 1941)

- Operation Krohcol (8 December 1941)

This was an advance by commonwealth forces into Thailand to destroy the main road at "The Ledge". The operation failed due to delays in authorisation by Percival and resistance by Thai police. - Sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse (10 December 1941)

The British battleship Prince of Wales and battlecruiser Repulse were sunk by Japanese aircraft after relying on false intelligence as to the location of the landings. They had no air support. This was the first time any capital ships at sea had been sunk by aircraft. - Battle of Jitra (11-13 December 1941)

- Battle of Kampar (1941)

- Battle of Slim River (1942)

- Battle of Gemas (1942)

- Battle of Muar (1942)

- Battle off Endau (1942)

See also

- Japanese invasion of Thailand

- Japanese occupation of Malaya

- Japanese order of battle during the Malayan Campaign

- Malaya Command-Order of Battle

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Frank Owen (2001). The Fall of Singapore. England: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-139133-2.

- ↑ L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Lieutenant-General Arthur Ernest Percival". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- 1 2 Sandhu 1987, p. 32.

- ↑ Wigmore 1957, p. 382

- ↑ Smith, Colin (2006). Singapore Burning. Penguin Books. p. 547. ISBN 0-14-101036-3.

- ↑ Nicholas Rowe, Alistair Irwin (21 September 2009). "Generals At War". 60 minutes in. National Geographic Channel. Missing or empty

|series=(help) - 1 2 3 Maechling, Charles. Pearl Harbor: The First Energy War. History Today. Dec. 2000

- ↑ Bayly/Harper, p. 110

- 1 2 Bayly/Harper, p. 107

- ↑ New Perspectives on the Japanese Occupation in Malaya and Singapore 1941–1945, Yōji Akashi and Mako Yoshimura, NUS Press, 2008, page 30, ISBN 9971692996, 9789971692995

- ↑ "OPENING OF HOSTILITIES". Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 L, Klemen (1999–2000). ""Seventy minutes before Pearl Harbor" The landing at Kota Bharu, Malaya, on December 7th 1941". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- 1 2 3 4 Squadron Leader W.J. Harper, 1946, "REPORT ON NO. 21 AND NO. 453 RAAF SQUADRONS" (UK Air Ministry), p.1 (Source: UK Public Records Office, ref. AIR 20/5578; transcribed by Dan Ford for Warbird's Forum.) Access date: 8 September 2007

- 1 2 "RAAF 21/453 Squadrons: the secret report". Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- 1 2 Harper report, p.1-2

- ↑ "Notable Brewster Buffalo pilots in Southeast Asia, 1941–42"

- ↑ "Aeroprints". Jon Field. Retrieved 2010-11-23

- ↑ Reading Room Manchester. "CWGC – Casualty Details". Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- 1 2 Peter Elphick, 2001, "Cover-ups and the Singapore Traitor Affair" Access date: 5 March 2007.

- ↑ The Second World War: Asia and the Pacific, By Jack W. Dice

- ↑ Bayly/Harper, p. 119

- ↑ "WITHDRAWAL FROM NORTH MALAYA". Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- ↑ Britain's Greatest Defeat. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ World War II Japanese Tank Tactics. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wigmore, Lionel (1957). "AWM Military Histories" (PDF). Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ↑ Video on YouTube

References/further information

- Bayly, Christopher / Harper, Tim: Forgotten Armies. Britain's Asian Empire and the War with Japan. Penguin Books, London, 2005

- Bose, Romen, "Secrets of the Battlebox: The Role and history of Britain's Command HQ during the Malayan Campaign", Marshall Cavendish, Singapore, 2005

- Burton, John (2006). Fortnight of Infamy: The Collapse of Allied Airpower West of Pearl Harbor. US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-096-X.

- Cull, Brian (2004). Hurricanes Over Singapore: RAF, RNZAF and NEI Fighters in Action Against the Japanese Over the Island and the Netherlands East Indies, 1942. Grub Street Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904010-80-7.

- Cull, Brian (2008). Buffaloes over Singapore: RAF, RAAF, RNZAF and Dutch Brewster Fighters in Action Over Malaya and the East Indies 1941–1942. Grub Street Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904010-32-6.

- Dixon, Norman F, On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, London, 1976

- Falk, Stanley L. (1975). Seventy days to Singapore: The Malayan Campaign, 1941–1942. Hale. ISBN 0-7091-4928-X.

- Kelly, Terence (2008). Hurricanes Versus Zeros: Air Battles over Singapore, Sumatra and Java. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-622-1.

- L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942".

- Seki, Eiji. (2006). Mrs. Ferguson's Tea-Set, Japan and the Second World War: The Global Consequences Following Germany's Sinking of the SS Automedon in 1940. London: Global Oriental. ISBN 978-1-905246-28-1 (cloth) [reprinted by University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2007 – previously announced as Sinking of the SS Automedon and the Role of the Japanese Navy: A New Interpretation.]

- Shores, Christopher F; Cull, Brian; Izawa, Yasuho. Bloody Shambles, The First Comprehensive Account of the Air Operations over South-East Asia December 1941 – April 1942 Volume One: Drift to War to the Fall of Singapore. London: Grub Street Press. (1992) ISBN 0-948817-50-X

- Smyth, John George Smyth, Percival and the Tragedy of Singapore, MacDonald and Company, 1971

- Thompson, Peter, The Battle for Singapore, London, 2005, ISBN 0-7499-5068-4 (HB)

- Wigmore, Lionel (1957). The Japanese Thrust. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 1 – Army. Volume 4. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3134219.

- Gurcharn Singh Sandhu, The Indian cavalry: history of the Indian Armoured Corps, Volume 2, Vision Books, 1978 ISBN 8170940044, 9788170940043

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malayan Campaign. |

- COFEPOW – The Armed Forced – The Campaign in Malaya

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and the Second World War – the Far East

- Australia's War 1939–1945: Battle of Malaya

- Animated History of the Fall of Malaya and Singapore

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||