Mahdist Sudan

| Mahdist State | |||||

| الدولة المهدية Al-Dawla al-Mahdiyah | |||||

| Unrecognized state | |||||

| |||||

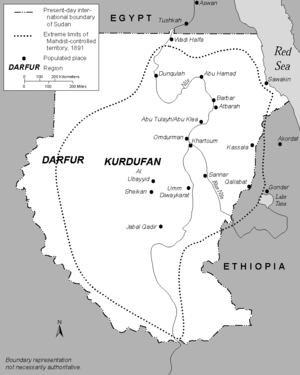

Extreme limits of Mahdist-controlled territory (1891) | |||||

| Capital | Omdurman | ||||

| Languages | Arabic and other languages of Sudan | ||||

| Religion | Messianic Islam | ||||

| Government | Islamic state | ||||

| Mahdi | |||||

| • | 1881–1885 | Muhammad Ahmad | |||

| Khalifa | |||||

| • | 1885–1899 | Abdallahi ibn Muhammad | |||

| Legislature | State Council (advisory)[1] | ||||

| Historical era | Scramble for Africa | ||||

| • | Mahdist revolt | 1881–1885 | |||

| • | Fall of Khartoum | 26 January 1885 | |||

| • | Sudan Convention | 18 January 1899 | |||

| • | Battle of Umm Diwaykarat | 24 November 1899 | |||

| Population | |||||

| • | Pre-Mahdist[2] est. | 7,000,000 | |||

| • | Post-Mahdist[2] est. | 2,000,000–3,000,000 | |||

| Currency | Legal tender:[3] Riyal maqbul (silver) De facto currencies:[3] Ottoman riyal majidi, Spanish dollar, Maria Theresa thaler | ||||

| Today part of | | ||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Sudan | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Before 1956 | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Since 1955 | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| By region | ||||||||||||||||

| By topic | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||

| Sudan portal | ||||||||||||||||

Mahdist Sudan was an unrecognized state that attempted unsuccessfully to break Egyptian rule in the Sudan. Developments in Sudan during the late 19th century were heavily influenced by the British position in Egypt. In 1869, the Suez Canal opened and quickly became Britain's economic lifeline to India and the Far East. To defend this waterway, Britain sought a greater role in Egyptian affairs. In 1873, the British government therefore supported a programme whereby an Anglo-French debt commission assumed responsibility for managing Egypt's fiscal affairs. This commission eventually forced khedive Ismail to abdicate in favor of his more politically acceptable son, Tawfiq (1877–1892).

After the removal in 1877 of Ismail, who had appointed him to the post, Charles George Gordon resigned as governor general of Sudan in 1880. His successors lacked direction from Cairo and feared the political turmoil that had engulfed Egypt. As a result, they failed to continue the policies Gordon had put in place. The illegal slave trade revived, although not enough to satisfy the merchants whom Gordon had put out of business. The Sudanese army suffered from a lack of resources, and unemployed soldiers from disbanded units troubled garrison towns. Tax collectors arbitrarily increased taxation.

Muhammad Ahmad

In this troubled atmosphere, Muhammad Ahmad ibn as Sayyid Abd Allah, a fakir, or holy man, who combined personal magnetism with religious zealotry, emerged, determined to expel the Turks and restore Islam to its primitive purity. The son of a Dongola boatbuilder, Muhammad Ahmad had become the disciple of Muhammad ash Sharif, the head of the Sammaniyah order. Later, as a sheikh of the order, Muhammad Ahmad spent several years in seclusion and gained a reputation as a mystic and teacher. In 1880, he became a Sammaniyah.

Even after the Mahdi proclaimed a jihad, or holy war, against the Turkiyah, Khartoum dismissed him as a religious fanatic. The government paid more attention when his religious zeal turned to denunciation of tax collectors. To avoid arrest, the Mahdi and a party of his followers, the Ansar, made a long march to Kurdufan, where he gained a large number of recruits, especially from the Baggara. From a refuge in the area, he wrote appeals to the sheikhs of the religious orders and won active support or assurances of neutrality from all except the pro-Egyptian Khatmiyyah. Merchants and Arab tribes that had depended on the slave trade responded as well, along with the Hadendoa Beja, who were rallied to the Mahdi by an Ansar captain, Osman Digna.

Advancing attacks

Early in 1882, the Ansar, armed with spears and swords, overwhelmed a British-led 7,000-man Egyptian force not far from Al Ubayyid and seized their rifles, field guns and ammunition. The Mahdi followed up this victory by laying siege to Al Ubayyid and starving it into submission after four months. The Ansar, 30,000 men strong, then defeated an 8,000-man Egyptian relief force at Sheikan. Next the Mahdi captured Darfur and imprisoned Rudolf Carl von Slatin, an Austrian in the khedive's service, who later became the first Egyptian-appointed governor of Darfur Province.

The advance of the Ansar and the Hadendowa rising in the east imperiled communications with Egypt and threatened to cut off garrisons at Khartoum, Kassala, Sennar, and Suakin and in the south. To avoid being drawn into a costly military intervention, the British government ordered an Egyptian withdrawal from Sudan. Gordon, who had received a reappointment as governor general, arranged to supervise the evacuation of Egyptian troops and officials and all foreigners from Sudan.

British response

After reaching Khartoum in February 1884, Gordon soon realized that he could not extricate the garrisons. As a result, he called for reinforcements from Egypt to relieve Khartoum. Gordon also recommended that Zubayr, an old enemy whom he recognized as an excellent military commander, be named to succeed him to give disaffected Sudanese a leader other than the Mahdi to rally behind. London rejected this plan. As the situation deteriorated, Gordon argued that Sudan was essential to Egypt's security and that to allow the Ansar a victory there would invite the movement to spread elsewhere.

Increasing British popular support for Gordon eventually forced Prime Minister William Gladstone to mobilize a relief force under the command of Lord Garnet Joseph Wolseley. A "flying column" sent overland from Wadi Halfa across the Bayuda Desert bogged down at Abu Tulayh (commonly called Abu Klea), where the Hadendowa broke the British line. An advance unit that had gone ahead by river when the column reached Al Matammah arrived at Khartoum on 28 January 1885, to find the town had fallen two days earlier. The Ansar had waited for the Nile flood to recede before attacking the poorly defended river approach to Khartoum in boats, slaughtering the garrison, killing Gordon, and delivering his head to the Mahdi's tent. Kassala and Sennar fell soon after, and by the end of 1885, the Ansar had begun to move into the southern region. In all Sudan, only Sawakin, reinforced by Indian army troops, and Wadi Halfa on the northern frontier remained in Anglo-Egyptian hands.

Mahdiyah

The Mahdiyah (Mahdist regime) imposed traditional Sharia Islamic laws. Sudan's new ruler also authorized the burning of lists of pedigrees and books of law and theology because of their association with the old order and because he believed that the former accentuated tribalism at the expense of religious unity.

The Mahdiyah has become known as the first genuine Sudanese nationalist government. The Mahdi maintained that his movement was not a religious order that could be accepted or rejected at will, but that it was a universal regime, which challenged man to join or to be destroyed. The Mahdi modified Islam's five pillars to support the dogma that loyalty to him was essential to true belief. The Mahdi also added the declaration "and Muhammad Ahmad is the Mahdi of God and the representative of His Prophet" to the recitation of the creed, the shahada. Moreover, service in the jihad replaced the hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca, as a duty incumbent on the faithful. Zakat (almsgiving) became the tax paid to the state. The Mahdi justified these and other innovations and reforms as responses to instructions conveyed to him by God in visions.

The Mahdist regime was also known for its severe persecution of Christians in Sudan, including Copts.[4]

The Khalifa

Six months after the capture of Khartoum, the Mahdi died of typhus (22 June 1885). The task of establishing and maintaining a government fell to his deputies—three caliphs chosen by the Mahdi in emulation of the Prophet Muhammad. Rivalry among the three, each supported by people of his native region, continued until 1891, when Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, with the help primarily of the Baqqara Arabs, overcame the opposition of the others and emerged as unchallenged leader of the Mahdiyah. Abdallahi—called the Khalifa (successor)—purged the Mahdiyah of members of the Mahdi's family and many of his early religious disciples.

Originally, the Mahdiyah functioned as a jihad state, run like a military camp. Sharia courts enforced Islamic law and the Mahdi's precepts, which had the force of law. After consolidating his power, the Khalifa instituted an administration and appointed Ansar (who were usually Baqqara) as amirs over each of the several provinces. The Khalifa also ruled over rich Al Jazirah. Although he failed to restore this region's commercial wellbeing, the Khalifa organized workshops to manufacture ammunition and to maintain river steamboats.

Regional relations remained tense throughout much of the Mahdiyah period, largely because of the Khalifa's commitment to using jihad to extend his version of Islam throughout the world. For example, the Khalifa rejected an offer of an alliance against the Europeans by Emperor Yohannes IV of Ethiopia (reigned 1871-1889). In 1887, a 60,000-man Ansar army invaded Ethiopia, penetrated as far as Gondar, and captured prisoners and booty. The Khalifa then refused to conclude peace with Ethiopia. In March 1889, an Ethiopian force, commanded by the emperor, marched on Metemma; however, after Yohannes fell in the ensuing Battle of Gallabat, the Ethiopians withdrew. Abd ar Rahman an Nujumi, the Khalifa's best general, invaded Egypt in 1889, but British-led Egyptian troops defeated the Ansar at Tushkah. The failure of the Egyptian invasion ended the Ansars' invincibility. The Belgians prevented the Mahdi's men from conquering Equatoria, and in 1893, the Italians repulsed an Ansar attack at Akordat (in Eritrea) and forced the Ansar to withdraw from Ethiopia.

Reconquest of Sudan

In 1892, Herbert Kitchener (later Lord Kitchener) became sirdar, or commander, of the Egyptian army and started preparations for the reconquest of Sudan. The British thought they needed to occupy Sudan in part because of international developments. By the early 1890s, British, French, and Belgian claims had converged at the Nile headwaters. Britain feared that the other colonial powers would take advantage of Sudan's instability to acquire territory previously annexed to Egypt. Apart from these political considerations, Britain wanted to establish control over the Nile to safeguard a planned irrigation dam at Aswan.

In 1895, the British government authorized Kitchener to launch a campaign to reconquer Sudan. Britain provided men and matériel while Egypt financed the expedition. The Anglo-Egyptian Nile Expeditionary Force included 25,800 men, 8,600 of whom were British. The remainder were troops belonging to Egyptian units that included six battalions recruited in southern Sudan. An armed river flotilla escorted the force, which also had artillery support. In preparation for the attack, the British established an army headquarters at the former rail head Wadi Halfa and extended and reinforced the perimeter defenses around Sawakin. In March 1896, the campaign started as the Dongola Expedition. Despite taking the time to reconstruct Ishma‘il Pasha's former 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge railway south along the east bank of the Nile, Kitchener captured the former capital of Nubia by September.[5] The next year, the British then constructed a new rail line directly across the desert from Wadi Halfa to Abu Hamad.[6] (The 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge, hastily adopted to make use of available rolling stock, meant supplies from the Egyptian network required transshipment via steamer from Asyut to Halfa. The Sudanese system retains the incompatible gauge to this day.) Anglo-Egyptian units fought a sharp action at Abu Hamad, but there was little other significant resistance until Kitchener reached Atbarah and defeated the Ansar. After this engagement, Kitchener's soldiers marched and sailed toward Omdurman, where the Khalifa made his last stand.

On 2 September 1898, the Khalifa committed his 52,000-man army to a frontal assault against the Anglo-Egyptian force, which was massed on the plain outside Omdurman. The outcome never was in doubt, largely because of superior British firepower. During the five-hour battle, about 11,000 Mahdists died, whereas Anglo-Egyptian losses amounted to 48 dead and fewer than 400 wounded.

Mopping-up operations required several years, but organized resistance ended when the Khalifa, who had escaped to Kurdufan, died in fighting at Umm Diwaykarat in November 1899. Many areas welcomed the downfall of his regime. Sudan's economy had been all but destroyed during his reign and the population had declined by approximately one-half because of famine, disease, persecution, and warfare. Millions had died in Sudan from foundation of the Mahdist state to its fall.[7][8][9][10] Moreover, none of the country's traditional institutions or loyalties remained intact. Tribes had been divided in their attitudes toward Mahdism, religious brotherhoods had been weakened, and orthodox religious leaders had vanished.

See also

References

- General

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies document "Sudan: The Mahdiyah, 1884–98" by Thomas Ofcansky (retrieved on 5 August 2010).

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies document "Sudan: The Mahdiyah, 1884–98" by Thomas Ofcansky (retrieved on 5 August 2010).

- Specific

- ↑ Sidahmed, Abdel Salam; Sidahmed, Alsir (2005). "Khalifa's administration". Sudan. Contemporary Middle East. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-415-27417-3.

The Mahdist administration centred around the person of the Khalifa Abdullah, both as the ultimate authority as well as the prime mover of the administrative system and initiator of policy. It has been noted that the Khalifa used to consult with his closest aides (such as his brother Ya'qub, and son 'Uthman Shaykh al-Din), and occasionally call for a meeting of the 'State Council'—apparently an advisory council—to which the Mahdi's surviving companions were invited.

- 1 2 Metelits, Claire (2009). Inside Insurgency: Violence, Civilians, and Revolutionary Group Behavior. New York University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8147-9578-1.

Estimates cite that the population of Sudan fell from seven million before the Mahdist revolt to between two and three million after the end of the Mahdist era.

- 1 2 Abu Shouk, Ahmad Ibrahim; Bjørkelo, Anders, eds. (1996). "A note on currencies". The Public Treasury of the Muslims: Monthly Budgets of the Mahdist State in the Sudan, 1897. The Ottoman Empire and its heritage, v. 5. E. J. Brill. pp. xvii–xviii. ISBN 978-90-04-10358-0.

- ↑ Minority Rights Group International, World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Sudan : Copts, 2008, available at: http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/49749ca6c.html [accessed 21 December 2010]

- ↑ Gleichen, Edward ed. The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: A Compendium Prepared by Officers of the Sudan Government, Vol. 1, p. 99. Harrison & Sons (London), 1905. Accessed 13 Feb 2014.

- ↑ Sudan Railway Corporation. "Historical Background". 2008. Accessed 13 Feb 2014.

- ↑ Francis Mading Deng, War of Visions: Conflict of Identities in the Sudan (1995) p.51

- ↑ Jok Madut Jok, War and Slavery in Sudan (2001) p.75

- ↑ Edward Spiers, Sudan: The Reconquest Reappraised (1998) p.12

- ↑ Henry Cecil Jackson, Osman Digna (1926) p.185

Bibliography

- Dr. Mohamed H. Fadlalla, Short History of Sudan, iUniverse, 30 April 2004, ISBN 0-595-31425-2

- Dr. Mohamed Hassan Fadlalla, The Problem of Dar Fur, iUniverse, Inc. (21 July 2005), ISBN 978-0-595-36502-9

- Dr. Mohamed Hassan Fadlalla, UN Intervention in Dar Fur, iUniverse, Inc. (9 February 2007), ISBN 0-595-42979-3

Coordinates: 14°30′00″N 32°40′00″E / 14.5000°N 32.6667°E