Magneto-optic effect

A magneto-optic effect is any one of a number of phenomena in which an electromagnetic wave propagates through a medium that has been altered by the presence of a quasistatic magnetic field. In such a material, which is also called gyrotropic or gyromagnetic, left- and right-rotating elliptical polarizations can propagate at different speeds, leading to a number of important phenomena. When light is transmitted through a layer of magneto-optic material, the result is called the Faraday effect: the plane of polarization can be rotated, forming a Faraday rotator. The results of reflection from a magneto-optic material are known as the magneto-optic Kerr effect (not to be confused with the nonlinear Kerr effect).

In general, magneto-optic effects break time reversal symmetry locally (i.e. when only the propagation of light, and not the source of the magnetic field, is considered) as well as Lorentz reciprocity, which is a necessary condition to construct devices such as optical isolators (through which light passes in one direction but not the other).

Two gyrotropic materials with reversed rotation directions of the two principal polarizations, corresponding to complex-conjugate ε tensors for lossless media, are called optical isomers.

Gyrotropic permittivity

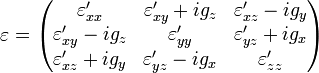

In particular, in a magneto-optic material the presence of a magnetic field (either externally applied or because the material itself is ferromagnetic) can cause a change in the permittivity tensor ε of the material. The ε becomes anisotropic, a 3×3 matrix, with complex off-diagonal components, depending of course on the frequency ω of incident light. If the absorption losses can be neglected, ε is a Hermitian matrix. The resulting principal axes become complex as well, corresponding to elliptically-polarized light where left- and right-rotating polarizations can travel at different speeds (analogous to birefringence).

More specifically, for the case where absorption losses can be neglected, the most general form of Hermitian ε is:

or equivalently the relationship between the displacement field D and the electric field E is:

where  is a real symmetric matrix and

is a real symmetric matrix and  is a real pseudovector called the gyration vector, whose magnitude is generally small compared to the eigenvalues of

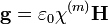

is a real pseudovector called the gyration vector, whose magnitude is generally small compared to the eigenvalues of  . The direction of g is called the axis of gyration of the material. To first order, g is proportional to the applied magnetic field:

. The direction of g is called the axis of gyration of the material. To first order, g is proportional to the applied magnetic field:

where  is the magneto-optical susceptibility (a scalar in isotropic media, but more generally a tensor). If this susceptibility itself depends upon the electric field, one can obtain a nonlinear optical effect of magneto-optical parametric generation (somewhat analogous to a Pockels effect whose strength is controlled by the applied magnetic field).

is the magneto-optical susceptibility (a scalar in isotropic media, but more generally a tensor). If this susceptibility itself depends upon the electric field, one can obtain a nonlinear optical effect of magneto-optical parametric generation (somewhat analogous to a Pockels effect whose strength is controlled by the applied magnetic field).

The simplest case to analyze is the one in which g is a principal axis (eigenvector) of  , and the other two eigenvalues of

, and the other two eigenvalues of  are identical. Then, if we let g lie in the z direction for simplicity, the ε tensor simplifies to the form:

are identical. Then, if we let g lie in the z direction for simplicity, the ε tensor simplifies to the form:

Most commonly, one considers light propagating in the z direction (parallel to g). In this case the solutions are elliptically polarized electromagnetic waves with phase velocities  (where μ is the magnetic permeability). This difference in phase velocities leads to the Faraday effect.

(where μ is the magnetic permeability). This difference in phase velocities leads to the Faraday effect.

For light propagating purely perpendicular to the axis of gyration, the properties are known as the Cotton-Mouton effect and used for a Circulator.

Kerr Rotation and Kerr Ellipticity

Kerr Rotation and Kerr Ellipticity are changes in the polarization of incident light which comes in contact with a gyromagnetic material. Kerr Rotation is a rotation in the angle of transmitted light, and Kerr Ellipticity is the ratio of the major to minor axis of the ellipse traced out by elliptically polarized light on the plane through which it propagates. Changes in the orientation of polarized incident light can be quantified using these two properties.

According to classical physics, the speed of light varies with the permittivity of a material:

where  is the velocity of light through the material,

is the velocity of light through the material,  is the material permittivity, and

is the material permittivity, and  is the material permeability. Because the permittivity is anisotropic, polarized light of different orientations will travel at different speeds.

is the material permeability. Because the permittivity is anisotropic, polarized light of different orientations will travel at different speeds.

This can be better understood if we consider a wave of light that is circularly polarized (seen to the right). If this wave interacts with a material at which the horizontal component (green sinusoid) travels at a different speed than the vertical component (blue sinusoid), the two components will fall out of the 90 degree phase difference (required for circular polarization) changing the Kerr Ellipticity.

A change in Kerr Rotation is most easily recognized in linearly polarized light, which can be separated into two Circularly polarized components: Left-Handed Circular Polarized (LCP) light and Right-Handed Circular Polarized (RCP) light. The anisotropy of the Magneto Optic material permittivity causes a difference in the speed of LCP and RCP light, which will cause a change in the angle of polarized light. Materials that exhibit this property are known as Birefringent.

From this rotation, we can calculate the difference in orthogonal velocity components, find the anisotropic permittivity, find the gyration vector, and calculate the applied magnetic field  .

.

Wavelength parallel measurement of magneto-optical effect

Because the MO activity is usually very small, normally less than 1°,in conventional systems, the monochromator produces quasi-monochromatic light in a narrow wavelength window since the amplitude of modulation is wavelength dependent. Therefore, to measure the spectroscopic MO activity, a large number of measurements over the full spectra is required to obtain satisfactory wavelength resolution and thus is very time consuming. To obtain the spectroscopic information of the MO activity, light wavelength is varied by the monochromator. Therefore, these methods cost huge amount of time though provide high sensitivity to small MO activities. Fast spectroscopic characterization of the MO activity is thus desirable. Can we use white light source and perform wavelength-parallel measurement such as that in the state-of-art ellipsometry for the characterization of refractive index?

It is well established that when this linear polarized light passes through another polarizer, also called analyzer, the transmitted light intensity could be varied depending on their relative angle θ governed by a cos2(θ) law. Based on this simple idea, now researcher has developed a fast spectroscopic MO system, they can get full spectral range MO activity in a single magnetic field scan. The system requires only stable continuous spectral light source, two polarizers, an achromatic quarter-wave plate and a spectrometer.

It is low cost and flexible for application in full spectral range from UV to IR, or even in THz applications.This new system would booster the exploration to the MO characteristics of a large variety of materials in the full spectral range. The minimum resolvable angle depends on the full scale signal of light source and is limited by the instability and dark noise of the spectrometer. A minimum resolvable angle of 0.004° has been demonstrated in the their configuration.[1]

See also

References

- ↑ G. X., Du; S. Saito; M. Takahashi (2012). "Fast magneto-optical spectrometry by spectrometer". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 83 (1). Bibcode:2012RScI...83a3103D. doi:10.1063/1.3673638. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- Federal Standard 1037C and from MIL-STD-188

- Lev Davídovich Landau; Evgeniĭ Mikhaĭlovich Lifshit︠s︡ (1960). Electrodynamics of continuous media. Pergamon Press. p. 82. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- Jackson, John David (1998). Classical electrodynamics (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. pp. 6–10. ISBN 978-0471309321.

- Jonsson, Fredrik; Flytzanis, Christos (1 November 1999). "Optical parametric generation and phase matching in magneto-optic media". Optics Letters 24 (21): 1514. Bibcode:1999OptL...24.1514J. doi:10.1364/OL.24.001514.

- Pershan, P. S. (1 January 1967). "Magneto-Optical Effects". Journal of Applied Physics 38 (3): 1482. Bibcode:1967JAP....38.1482P. doi:10.1063/1.1709678.

- Freiser, M. (1 June 1968). "A survey of magnetooptic effects". IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 4 (2): 152–161. Bibcode:1968ITM.....4..152F. doi:10.1109/TMAG.1968.1066210.

- Broad band magneto-optical spectroscopy

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".