Macrolide

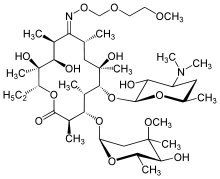

The macrolides are a class of natural products that consist of a large macrocyclic lactone ring to which one or more deoxy sugars, usually cladinose and desosamine, may be attached. The lactone rings are usually 14-, 15-, or 16-membered. Macrolides belong to the polyketide class of natural products. Some macrolides have antibiotic or antifungal activity and are used as pharmaceutical drugs.

Examples

Antibiotic macrolides

US FDA-approved :

- Azithromycin - unique; does not inhibit CYP3A4

- Clarithromycin

- Erythromycin

- Fidaxomicin

- Telithromycin

Non-US FDA-approved:

- Carbomycin A

- Josamycin

- Kitasamycin

- Midecamycin/midecamycin acetate

- Oleandomycin

- Solithromycin

- Spiramycin - approved in the EU, and in other countries

- Troleandomycin - used in Italy and Turkey

- Tylosin/tylocine - used in animals

- Roxithromycin

Ketolides

Ketolides are a class of antibiotics that are structurally related to the macrolides. They are used to treat respiratory tract infections caused by macrolide-resistant bacteria. Ketolides are especially effective, as they have two ribosomal binding sites.

Ketolides include:

- Telithromycin - the first and only approved ketolide

- Cethromycin

Fluoroketolides

Fluoroketolides are a class of antibiotics that are structurally related to the ketolides. The fluoroketolides have three ribosomal interaction sites.

Fluoroketolides include:

- Solithromycin - the first and currently the only fluoroketolide (not yet approved)

Non-antibiotic macrolides

The drugs tacrolimus, pimecrolimus, and sirolimus, which are used as immunosuppressants or immunomodulators, are also macrolides. They have similar activity to cyclosporin.

Antifungal drugs

Polyene antimycotics, such as amphotericin B, nystatin etc., are a subgroup of macrolides.[1]

Toxic macrolides

A variety of toxic macrolides produced by bacteria have been isolated and characterized, such as the mycolactones.

Uses

Antibiotic macrolides are used to treat infections caused by Gram-positive (e.g., Streptococcus pneumoniae) and limited Gram-negative (e.g., Bordetella pertussis, Haemophilus influenzae) bacteria, and some respiratory tract and soft-tissue infections.[2] The antimicrobial spectrum of macrolides is slightly wider than that of penicillin, and, therefore, macrolides are a common substitute for patients with a penicillin allergy. Beta-hemolytic streptococci, pneumococci, staphylococci, and enterococci are usually susceptible to macrolides. Unlike penicillin, macrolides have been shown to be effective against Legionella pneumophila, mycoplasma, mycobacteria, some rickettsia, and chlamydia.

Macrolides are not to be used on non-ruminant herbivores, such as horses and rabbits. They rapidly produce a reaction causing fatal digestive disturbance.[3] It can be used in horses less than one year old, but care must be taken that other horses (such as a foal's mother) do not come in contact with the macrolide treatment.

Mechanism of action

Antibacterial

Macrolides are protein synthesis inhibitors. The mechanism of action of macrolides is inhibition of bacterial protein biosynthesis, and they are thought to do this by preventing peptidyltransferase from adding the growing peptide attached to tRNA to the next amino acid[4] (similarly to chloramphenicol[5]) as well as inhibiting ribosomal translation.[4] Another potential mechanism is premature dissociation of the peptidyl-tRNA from the ribosome.[6]

Macrolide antibiotics do so by binding reversibly to the P site on the subunit 50S of the bacterial ribosome. This action is considered to be bacteriostatic. Macrolides are actively concentrated within leukocytes, and are, therefore, transported into the site of infection.[7]

Immunomodulation

Diffuse panbronchiolitis

The macrolide antibiotics erythromycin, clarithromycin, and roxithromycin have proven to be an effective long-term treatment for the idiopathic, Asian-prevalent lung disease diffuse panbronchiolitis (DPB).[8][9] The successful results of macrolides in DPB stems from controlling symptoms through immunomodulation (adjusting the immune response),[9] with the added benefit of low-dose requirements.[8]

With macrolide therapy in DPB, great reduction in bronchiolar inflammation and damage is achieved through suppression of not only neutrophil granulocyte proliferation but also lymphocyte activity and obstructive secretions in airways.[8] The antimicrobial and antibiotic effects of macrolides, however, are not believed to be involved in their beneficial effects toward treating DPB.[10] This is evident, as the treatment dosage is much too low to fight infection, and in DPB cases with the occurrence of the macrolide-resistant bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa, macrolide therapy still produces substantial anti-inflammatory results.[8]

Resistance

The primary means of bacterial resistance to macrolides occurs by post-transcriptional methylation of the 23S bacterial ribosomal RNA. This acquired resistance can be either plasmid-mediated or chromosomal, i.e., through mutation, and results in cross-resistance to macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins (an MLS-resistant phenotype).

Two other types of acquired resistance rarely seen include the production of drug-inactivating enzymes (esterases or kinases), as well as the production of active ATP-dependent efflux proteins that transport the drug outside of the cell.

Azithromycin has been used to treat strep throat (Group A streptococcal (GAS) infection caused by Streptococcus pyogenes) in penicillin-sensitive patients, however macrolide-resistant strains of GAS are not uncommon. Cephalosporin is another option for these patients.

Side-effects

A 2008 British Medical Journal article highlights that the combination of some macrolides and statins (used for lowering cholesterol) is not advisable and can lead to debilitating myopathy.[11] This is because some macrolides (clarithromycin and erythromycin, not azithromycin) are potent inhibitors of the cytochrome P450 system, particularly of CYP3A4. Macrolides, mainly erythromycin and clarithromycin, also have a class effect of QT prolongation, which can lead to torsades de pointes. Macrolides exhibit enterohepatic recycling; that is, the drug is absorbed in the gut and sent to the liver, only to be excreted into the duodenum in bile from the liver. This can lead to a build-up of the product in the system, thereby causing nausea. In infants the use of erythromycin has been associated with pyloric stenosis.[12][13]

Some macrolides are also known to cause cholestasis.[14]

References

- ↑ Hamilton-Miller, JM (1973). "Chemistry and Biology of the Polyene Macrolide Antibiotics". Bacteriological Reviews (American Society for Microbiology) 37 (2): 166–196. PMC 413810. PMID 4578757.

- ↑ http://www.emedexpert.com/compare/macrolides.shtml

- ↑ Giguere, S.; Prescott, J. F.; Baggot, J. D.; Walker, R. D.; Dowling, P. M., ed. (2006). Antimicrobial Therapy in Veterinary Medicine (4th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-8138-0656-3.

- 1 2 Protein synthesis inhibitors: macrolides mechanism of action animation. Classification of agents Pharmamotion. Author: Gary Kaiser. The Community College of Baltimore County. Retrieved on July 31, 2009

- ↑ Drainas, D; Kalpaxis, DL; Coutsogeorgopoulos, C (1987). "Inhibition of ribosomal peptidyltransferase by chloramphenicol. Kinetic studies". European Journal of Biochemistry / FEBS 164 (1): 53–8. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb10991.x. PMID 3549307.

- ↑ Tenson, T.; Lovmar, M.; Ehrenberg, M. (2003). "The Mechanism of Action of Macrolides, Lincosamides and Streptogramin B Reveals the Nascent Peptide Exit Path in the Ribosome". Journal of Molecular Biology 330 (5): 1005–1014. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00662-4. PMID 12860123.

- ↑ Bailly, S; Pocidalo, J J; Fay, M; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M A (1991). "Differential modulation of cytokine production by macrolides: Interleukin-6 production is increased by spiramycin and erythromycin". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 35 (10): 2016–9. doi:10.1128/AAC.35.10.2016. PMC 245317. PMID 1759822.

- 1 2 3 4 Keicho; N.; Kudoh, S.; (2002). "Diffuse panbronchiolitis: role of macrolides in therapy". American Journal of Respiratory Medicine 1 (2): 119–131. doi:10.1007/BF03256601. PMID 14720066.

- 1 2 Lopez-Boado, Y. S.; Rubin, B. K. (2008). "Macrolides as immunomodulatory medications for the therapy of chronic lung diseases". Current Opinion in Pharmacology 8 (3): 286–291. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2008.01.010. PMID 18339582.

- ↑ Schultz, M. J. (2004). "Macrolide activities beyond their antimicrobial effects: macrolides in diffuse panbronchiolitis and cystic fibrosis". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 54 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh309. PMID 15190022.

- ↑ Sathasivam, S.; Lecky, B. (November 2008). "Statin induced myopathy". British Medical Journal 337: a2286. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2286. PMID 18988647.

- ↑ Sanfilippo, A. (1976). "Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis related to ingestion of erythromycine estolate: A report of five cases". Journal of Pediatric Surgery 11 (2): 177–180. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(76)90283-9. PMID 1263054.

- ↑ Honein, M. A.; Paulozzi, L. J.; Himelright, I. M.; Lee, B.; Cragan, J. D.; Patterson, L.; Correa, A.; Hall, S.; Erickson, J. D. (1999). "Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis after pertussis prophylaxis with erythromcyin: A case review and cohort study". Lancet 354 (9196): 2101–2105. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)10073-4. PMID 10609814.

- ↑ Hautekeete, ML (1995). "Hepatotoxicity of antibiotics". Acta gastro-enterologica Belgica 58 (3–4): 290–6. PMID 7491842.

External links

- Ōmura, S. (2002). Macrolide antibiotics: chemistry, biology, and practice (2nd ed.). Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-526451-8.

- Structure Activity Relationships "Antibacterial Agents; Structure Activity Relationships", André Bryskier MD; beginning at pp143

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||