Macchi C.202

| C.202 Folgore | |

|---|---|

| |

| C.202 of Regia Aeronautica 168ª Squadriglia, 54° Stormo CT c.1943 | |

| Role | Fighter |

| Manufacturer | Macchi Aeronautica |

| Designer | Mario Castoldi |

| First flight | 10 August 1940 |

| Introduction | July 1941 |

| Retired | 1951 |

| Primary user | Regia Aeronautica |

| Number built | Over 1,100[1] |

| Variants | Macchi C.205 |

The Macchi C.202 Folgore (Italian "thunderbolt") was a World War II fighter aircraft built by Macchi Aeronautica and operated mainly by the Regia Aeronautica (RA; Royal (Italian) Air Force). Macchi aircraft designed by Mario Castoldi received the "C" letter in their model designation, hence the Folgore is referred to as the C.202 or MC.202. The C.202 was a development of the earlier C.200 Saetta, with an Italian-built version of the Daimler-Benz DB 601Aa engine and a redesigned, more streamlined fuselage.[2] Considered to be one of the best wartime fighters to serve in large numbers with the Regia Aeronautica,[3] the Folgore operated on all fronts in which Italy was involved.[4]

The Folgore went into service with the Regia Aeronautica in July 1941 and immediately proved to be an effective and deadly dogfighter.[5][6] The Australian ace Clive Caldwell, who fought a wide variety of German, Italian and Japanese fighters during 1941–45, later stated that the C.202 was "one of the best and most undervalued of fighters".[7] The C.202 also had its defects: like its predecessor, the Macchi C.200, it could enter a dangerous spin.[8] It was insufficiently armed, with just two machine guns that easily jammed. The radios were unreliable, forcing the pilots to communicate by waggling wings. The oxygen system was inefficient, causing 50 to 60 per cent of the pilots to break off missions, sometimes even causing fatal accidents.[2]

Development

The decision of the Italian military authorities to adopt radial engines meant that, during the second half of the 1930s, the Italian aeronautical industry failed to develop more powerful engines based on streamlined liquid-cooled designs.[9] This forced Macchi Aeronautica to rely on the ageing Fiat A.74 radial engine for its C.200 fighter. By 1941, the C.200, armed with two 12.7 mm (.50 in) machine guns and with a maximum speed of 504 km/h (315 mph), was obsolete.

In July 1939, the RA requested that Reggiane build a prototype Re.2000 with a German Daimler-Benz DB 601Aa, liquid-cooled supercharged inverted V-12 engine rated at 1,175 PS (1,159 hp, 864 kW); this became the Re.2001. At the time, the most powerful reliable Italian inline engine was the 715 kW (960 hp) Isotta Fraschini Asso XI R.C.40, which was designed in 1936. In November 1939, Alfa Romeo acquired the license to produce the DB 601Aa as the Alfa-Romeo RA.1000 R.C.41-I Monsone, which was to be used in the production of C.202s.

While they waited for Alfa Romeo production to start, Aeronautica Macchi imported a DB 601Aa engine; Macchi chief of design Mario Castoldi began to work on mating the Macchi C.200 wings, undercarriage, vertical and horizontal tail units with a new fuselage incorporating the imported DB 601Aa.[10] Design of the new fighter began in January 1940 and, less than seven months later, on 10 August 1940, the sole prototype, MM.445,[11] made its first flight, two months after Italy's entry into World War II.

From the first trials it was evident that the C.202 was an advanced design, mainly because of the use of the Daimler Benz DB 601, a departure from the standard practice of using engines of Italian origin.[4] Test results showed that Italy had caught up with Britain and Germany in the field of fighter airplanes.[2] The prototype differed in some respects from the production aircraft; the headrest fairing incorporated two windows for rear visibility, while production versions replaced this with a narrower, scalloped headrest. The square-sectioned supercharger air intake was replaced by an elongated round sectioned fairing, which was later redesigned to incorporate a dust filter. The prototype was flown to the Regia Aeronautica's main test airfield at Guidonia, where it met with an enthusiastic response from test pilots. A speed of 603 km/h (375 mph) was recorded, with 5,486 m (18,000 ft) being reached in six minutes and little of the good maneuverability of the C.200 was lost.[10] Another of its attributes was its extremely strong construction that allowed its pilots to dive the aircraft steeply.[12] Due to the flight test reports, the C.202 was immediately ordered into production with the first examples (built by Macchi as Serie II) appearing in May 1941. The complexity of the structure was not well suited to mass production, and resulted in a limited production rate compared to the Bf 109E/F (usually rated at 4,500–6,000 man-hours) while the Macchi needed 22,000 or more.[13] The growth of the C.202 project was slower than that of the Re. 2001; but, by employing both mass production techniques and less expensive advanced technologies, the production cost was slightly less than that of the Reggiane Re.2001, (525,000 lire vs 600,000); this latter, the only other DB 601 fighter in mass production, was slower and heavier (2.460/3.240 kg) [14] but had a bigger wing and a more advanced and adaptable structure.[15] Breda, Milan was also chosen to build the C.202 and eventually built the majority of the type. SAI-Ambrosini was another sub-contractor, building some 100 C.202s.[16]

Design

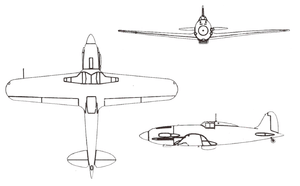

Castoldi, whose background included working on Schneider Trophy racers design, followed Celestino Rosatelli as the main designer of new fighters for the RA. His new project was robust and small, utilizing a conventional but complex structural arrangement based on his experience with wooden designs, and at the same time paying great attention to its aerodynamics (Castoldi designed the MC.72, the world's fastest aircraft of its time).

The wing and fuselage structures were of a conventional metal design, having a single vertical tail with two elevators, and a wing of relatively conventional design with two main spars and 23 ribs. The ailerons, elevators and rudder were metal structures with fabric covering. Apart from the ailerons, the entire trailing edge of the wing was dominated by a pair of all metal split flaps.[10] The undercarriage was of a standard design; the two widely set hydraulically operated main gears retracting inwardly into the wing, while the tail wheel was non-retractable. As with the C.200, to counteract the torque of the engine, Castoldi extended the left wing by 21 cm (8.5 inches). This meant that the left wing developed more lift, offsetting the tendency of the aircraft to roll to the left due to the rotation of the propeller.

The empty weight of the new C.202 (approximately 2,350 kg/5,180 lb) gradually increased throughout production, and due to the thickness of metal used it was also comparatively heavy, yet this class of aircraft was still considered lightweight compared to other contemporary fighter designs. The Macchi's mass was around 300 kg (660 lb) higher than the comparable Bf 109E German fighter, consequently, the power-to-weight ratio was considerably lower while wing loading was higher[17]

Australian air ace Clive Caldwell felt the Folgore would have been superior to the Messerschmitt Bf 109 had it been better armed.[18] The C.202 was lightly armed by the standards of the time carrying the same armament as the C.R.32, a 1933 design.[19] The C.202 carried as standard two 12.7 mm (.5 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns. The Breda design was as heavy as the Browning M2, the model from which it was derived. The Breda fired 12.7x81 mm "Vickers" ammunition, not 12.7x99 mm, with the result that the energy at the muzzle was 10,000 joules vs. 16,000. The rate of fire was about 18 rounds/second or 0.63 kg (1.39 lb).[20]

Initially, all the armament was fitted within the nose of the Macchi. Ammunition carried was up to 800 rounds (standard: 700 rounds). An additional pair of Breda 7.7 mm (.303 in) machine guns was fitted in the wings in the VII series onward, but these, along with 1,000 rounds of ammunition, added 100 kg (220 lb) to the aircraft's weight and were typically removed by pilots to save weight, since they were relatively ineffective against most enemy aircraft in 1942.[21] A synchronizing unit allowed the nose guns to fire through the propeller disk, but with a 25% loss in ROF (Rate of Fire).[22] A "San Giorgio" reflector gun sight was fitted.

The fuselage housed the main armament and the Alfa Romeo RA.1000 R.C.41-I Monsone engine which drove a Piaggio P1001 three-blade, variable-pitch, constant speed propeller. Situated behind the engine and under the 12.7 mm (.5 in) ammunition boxes there was a 270 L (71.3 US gal) self-sealing fuel tank. Another 80 L (21.1 US gal) fuel tank was placed behind the pilot, with two additional tanks, each with a capacity of 40 L (10.5 US gal), being housed in the wing roots; the total fuel capacity was 430 L (113.6 US gal) .[10] The main coolant radiator was housed in a rectangular fairing under the fuselage beneath the cockpit, and the oil cooler was placed under the nose within a streamlined, rectangular housing. From the cockpit aft, the fuselage was formed into a round monocoque structure; the aft fuselage tapered into the tail and contained the radio, oxygen and flight control mechanisms. The canopy was hinged on the starboard base and opened sideways. Behind the canopy the pilot's headrest was fixed to a triangular turn-over pylon which was covered by a streamlined, tapered fairing. This fairing was shaped into an inverted 'T' which enabled the pilot to have a reasonable field of view to the rear. The unpressurised cockpit had an armor plate fitted behind the armored seat for protection. While early C.202s had a very short "stub" radio mast projecting from the fairing, most used a tall, slim mast.[10]

On 21 August 1941, Tenente Giulio Reiner, one of the most skillful and experienced pilots of 9° Gruppo, flew the "military control flight" in Lonate Pozzolo, The Ufficio tecnico (Technical Bureau) recorded the maximum speed of 1,078.27 km/h in the Folgore in a vertical dive, with 5.8 G. forces while pulling out of the dive. Ingegner Mario Castoldi, the designer of the 202 questioned whether Reiner had properly flown the test. In fact, during the vertical dive, Reiner had to face very strong vibrations throughout the airframe and in the control stick, while the flying controls were locked and the propeller blades were jammed at maximum pitch. The clean aerodynamics offered by the inline engine permitted dive speeds high enough for pilots to encounter the then-unknown phenomenon of compressibility.[23]

Some defects of the new fighter could be easily fixed, such as the landing gear lowering inadvertently when pulling out of a steep dive, the machine gun bonnet that broke, the ammunition belts that jammed and the air cleaner intake that, because of the engine vibrations, first crystallized and then sheared itself. Other defects, like the unreliability of the radios and of the oxygen systems, and the limited armament, could not.[24]

Operational history

Service introduction

The Folgore was put into production using imported DB 601Aa engines, while Alfa Romeo set up production of the engine under license as the RA.1000 R.C.41-I Monsone (Monsoon). Due to initial delays in engine production, Macchi resorted to completing some C.202 airframes as C.200s with Fiat radial engines. Nevertheless, by late 1942, Folgores outnumbered all other fighter aircraft in the Regia Aeronautica.

The first units selected to be equipped with the C.202 Series I were the 17° and 6° Gruppi, from 1° Stormo, based at the airfield of Campoformido, near Udine, and the 9° Gruppo of 4° Stormo, based in Gorizia. Their pilots start to train on the new fighter in May–June 1941, at Lonate Pozzolo (Varese), the airfield of the Macchi.[25] Although deployed in mid-1941, the C.202 did not see action until later that fall, because of the many defects of the first machines. Some defects appeared similar to those on the early C. 200 version: on 3 August, during a mock dogfight, Sergente Maggiore Antonio Valle – an experienced pilot, credited with two kills in Marmarica and recipient of a Medaglia di Bronzo al Valor Militare (Bronze Medal to Military Valor) – at a height of 4,000 meters entered in a flat spin and could not recover or bail out, losing his life.[26]

On 29 July, the three first operational C.202s of 4° Stormo, 97a Squadriglia, landed at Merna airport.[27]

By November, C.202s appeared on the Libyan front. In addition to North Africa, the aircraft saw limited service on the Eastern Front where between 1941 and 1943, together with C.200s, they achieved an 88 to 15 victory/loss ratio.[23] But, according to other authors [28][29] that ratio refers only to the C.200 "Saetta".

On 23 December 1942, the “Regia Aeronautica” command with a circular letter authorized the use of under-wing jettisonable tanks, to increase the range of the C.202s of 6° and 7° Gruppo, based in Pantelleria.[30]

Following the Allied 1943 Armistice with Italy, C.202s were used as trainers in the Italian Social Republic (Repubblica Sociale Italiana, or RSI). After the war, two examples served as trainers in Lecce until 1947.

Allied pilots who flew against the Folgore were impressed with its performance and manoeuvrability.[31] The Macchi C.202 was considered superior to both the Hawker Hurricane and the Curtiss P-40 Kittyhawks it fought against, at first on the Libyan front, and the equal of the Spitfire Mk. V. The C.202 was able to out-turn all three, although the Spitfire had a superior rate of climb.[32] The C.202 could effectively fly against the Hurricane, Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Bell P-39 Airacobra, Curtiss P-40 and even the Spitfire at low altitudes, but the aircraft's combat effectiveness was somewhat hampered by its weak armament.[23]

Malta

The Folgore first saw service during the Siege of Malta on 29 or 30 September 1941; this first mission was intercepting British Hurricanes over Sicily.[33][34]

From early October 1941 the Italian units commenced extensive operations over Malta, which provided many opportunities for encounters with RAF fighters. From its initial combat missions, the C.202 displayed marked superiority over the Hawker Hurricane II which formed the island's main form of aerial defence at the time.[35] But the Macchi's main weakness, its weak armament, was a problem.[36] On the besieged island, the new Macchi fighter was not only used for fighter operations, but also for ground attacks and reconnaissance missions. Among the pilots who flew recce C.202s on Malta, was Adriano Visconti, later to become a famed ace, credited with at least 10 air victories.[36]

The presence of the Folgores in Maltese skies was to last only until the end of November, when most of the unit was transferred to the deteriorating North Africa front. The 4° Stormo returned to Sicily in April 1942 for a couple of weeks, before continuing its transfer to Campoformido. In the meantime, the 16° Gruppo had started to re-equip with the C.202s at the end of 1941. The Macchis of 51° Stormo and 23° Gruppo (3° Stormo) arrived in May 1942. During this time, the Axis had to give up the planned invasion of Malta (Operation C 3), aircraft and men being necessary elsewhere. At the end of June, about 60 C.202s could be mustered in Sicily to operate against Malta, which had started to receive the Spitfire Mk. V in considerable quantities.[37] On 7 March 1942, the carrier USS Wasp delivered the first Spitfires to Malta, and the Axis' air-superiority started to shift in favour of the Allies.[38] The Macchis often encountered Spitfires, with losses on both sides. Even if the Macchi could out-turn the Spitfire, the Folgores suffered from the lack of a more powerful armament and, without radios, the Regia Aeronautica pilots were forced to communicate by waggling their wings and, consequently, had to adopt too tight and less effective formations. They also suffered due to the lack of radar, which the RAF used successfully to vector their fighters.[39] C.202s were also involved in Operation Harpoon, clashing with Sea Hurricanes.

North Africa

On 26 November 1941, during Operation Crusader, 19 Macchis of 9° Gruppo, 4° Stormo were sent to Africa, in response to the British offensive. During its initial combats over the Western Desert, the Folgore was quite a surprise to British pilots and it remained a respected adversary.[40]

In the desert war, the SAS incursions behind the lines, led by men like "Paddy" Mayne were aimed at destroying aircraft at their bases. On the night of 28 December 1941, Macchi 202s of 1° Stormo were based at Uadi Tamet. They had been transferred from Italy one month before and recently relocated from El Merduma because this airbase was too exposed to SAS attacks but this did not help them. 1° Stormo had 60 fighters, 17°Gruppo around 30. In a month of combat this latter lost eight fighters. That night Mayne and his three comrades destroyed nine others. The Italians had placed much hope in these brand-new fighters but after this attack were forced to move them further back, well away from the front lines to avoid more losses.[41]

During 1942, Bf 109F/Gs and Macchi C.202s fought Allied air forces in the skies of North Africa. At the time of Rommel's offensive on Tobruk, 5° "Squadra aerea" ("Aviation Corps"), based in North Africa, had three Macchi wings: 1° Stormo had 47 C.202s (40 serviceable), 2° Stormo had 63 C.200s (52) while 4° Stormo had 57(47). This, coupled with the 32 Cant Z.1007s, was one of the most powerful fighter forces that the Italians fielded in the war, and constituted almost a tenth of the overall Folgore production.[5] In the meantime, some Macchi fighters were sent to the USSR to supplement the obsolete C.200s.

At the end of the year, the growing strength of the Allied forces was overwhelming and after the defeat in the skies over Malta as well as El-Alamein the last operational Axis units lost their air superiority in the Mediterranean. The Germans and the Italians succeeded in establishing a bridgehead in Tunisia, and later in December the Regia Aeronautica transferred four fighter squadrons there. The 5a Squadra Aerea, which had left Libya and retreated to the Tunisian regions, had previously repatriated all aircraft unsuitable for further action to Italy. On 21 February 1943, the 5a Squadra Aerea still had, in the northern sector, the 6°Gruppo C.T. with three squadrons of MC.202s at Sfax and Gammarat and in the southern sector, 3°Stormo with six squadrons of MC.200s and MC.202s at El Hamma. "Although these forces were quite insufficient they nevertheless achieved quite notable successes. The Macchis continued fighting while retreating to Tunisia and then in the defence of Sicily, Sardinia and Italy against an increasingly stronger opponent. The Macchis of two groups which landed at Korba airfield from Italy experienced one notable action. Forced to concentrate 40 C.202s (both 7° and 16°, 54° Stormo) on a Tunisian airfield, on 8 May 1943, almost all the C.202s were destroyed on the ground by marauding Spitfires. A contemporary photo showed over a dozen Macchi C.202s in an abandoned airfield, damaged beyond repair by air attacks or dismantled to support the last few operating fighters.[42] Because no transport aircraft were available every surviving fighter taking off the next day had two men inside, a pilot and a mechanic. Only a few aircraft (five of 7° and six of 16°) were repaired by 10 May 1943 and retreated to Italy. At least one, manned by Tenente Lombardo, was destroyed and the two men inside were wounded after crash-landing on a beach near Reggio Calabria.

Eastern Front operations

In May 1942, the 22° Gruppo Caccia, that had reached its operational limit, was replaced by the newly formed 21° Gruppo Autonomo C.T. composed of 356ª, 382ª, 361ª and 386ª Squadriglia. This unit, commanded by Maggiore (Major) Ettore Foschini, brought new C.202s and 18 new Macchi C.200 fighters.[43] In August 1942, at the beginning of the German offensive they were deployed at the Stalino, Lughansk, Kantemirovka and Millerovo airfields, fighting against the Red Army positions on the east Don river during October–November 1942. the fighters operated in adverse climate conditions (40° to 45° below zero and heavy snow storms) while under heavy Russian fighter-bomber harassment.Under these circumstances, 21° Gruppo – which had 17 C.202s on strength – rarely flew sorties. Only a total of 17 missions were flown with Folgores on the Eastern Front during a four-month period.[44] The C.202s were forced to escort C.200s alongside Fiat BR.20Ms and Caproni Ca.311s in attacks against Soviet columns, while facing great numbers of new VVS' fighters. The C.202s also escorted CANT Z.1007bis in reconnaissance missions and German transport aircraft. One of these missions was the escort to Junkers Ju 52s flying to Stalingrad, on 11 December 1942, during which Tenente Pilota Gino Lionello was shot down and had to bail out from his Folgore.[44]

After the abandonment of advanced airfields between December 1942 – January 1943 at Voroshilovgrad, Stalino and Tscerkow, the Italian air units operated in defensive actions against a more potent Soviet air offensive, mainly using Ilyushin IL-2s Shturmoviks and Petlyakov Pe-2s. In March 1943, the Corpo Aereo Italiano was detached to Odessa airbase joining Reggiane Re. 2000 Héja I of the Hungarian MKHL 1 and 2/1 Vadászszázad and IAR 80C and Bf 109E/G of Romanian FARR 4 and 5 detached at same base and Saki (Crimea) in a holding action against the V-Vs armada of 2,000 aircraft, at a time when Axis air forces only countered with 300 operative aircraft with very small quantities of fuel, munitions and equipment.

The last effective operation of Corpo Aereo Italiano in Russia occurred on 17 January 1943, when one mixed formation of 25 surviving Macchi fighters (out of a remaining total of 30 C.200s and nine C.202s) attacked Red Army armored and motorized infantry columns to support German and Italian units encircled in Millerovo.[45]

Sicilian and Italian campaigns

The C.202s played a significant role in the defense of Sicily and Southern Italy against bombing attacks launched by the USAF, but by the time of Allied invasion of Sicily (10 July 1943) they were less effective as attrition had reduced the number available,[3] while 20 mm cannons were needed to cause enough damage, so Bf 109F/Gs, Macchi MC.205s and Fiat G.55s replaced C.202s as soon as possible. Mixed units (such as the 51° Stormo, Sardinia) were formed with C.202s often serving with C.205s.

At the Armistice, there were only 186 Folgores, with 100 aircraft still serviceable.[46] Several C.202s also served with the Italian Co-Belligerent Air Force, and some were transformed into C.205s or C.202/205 with the Veltro's engine. Others served as trainers in the Aeronautica Nazionale Repubblicana (National Republican Air Force) of the Italian Social Republic (RSI) and the Luftwaffe (German Air Force). Switzerland ordered 20 C.202s, but none were delivered, because at that time (12 May 1943), Italy no longer had the capability to export these types of aircraft.[47][48] 12 C.202s and probably another 12 were delivered to the Croatian Air Force Legion for operational use against the RAF and USAAF over Croatia in mid-1944, all ex-LW fighters.[47][48]

After the bombing of Macchi Industries in 1944, the combat career of the C.202 and C.205 was nearly over. Post-war some aircraft survived along with newly manufactured C.205s to serve in Italy; C.202s were operational until 1948. The Royal Egyptian Air Force ordered a total of 42 C.205s, but 31 were re-engined Folgores (C.202s) armed with only two 12.7 mm Breda machine guns. Some of these aircraft fought against Israel, and were in service until 1951.[49]

In Croatian service

About 20–22 C.202s were used by Croatia as interceptors of Allied bombers.[50] During 1944, the Air Force of the Independent State of Croatia, Zrakoplovstvo Nezavisne Države Hrvatske (ZNDH), received several batches of Macchi C.202s. In January, eight brand-new Folgore arrived at Zagreb's Lucko airfield. Another four arrived two weeks later, but one was lost during a test-flight. The first batch of "Folgore" delivered to the ZNDH (16 aircraft) was from the XII series built by Breda after the German occupation of Italy. They equipped Kroat. JGr 1. These aircraft retained their Luftwaffe markings whilst in service with the unit. 1944 had seen the return of the Croatian Air Force Legion (HZL) fighter squadron to Croatia from service on the Eastern Front. Upon its return the HZL was redesignated Kroat. JGr 1 and its operational fighter squadron was redesignated 2./(Kroat.)JGr. This unit was equipped with Macchis. A second training / operational conversion squadron was also formed, designated 3./(Kroat.)JGr and equipped with Fiat G.50, Macchi C.200 and Fiat CR.42 fighters. In March they were scrambled for the first time against an American raid west of Zagreb, but combat was avoided: Croatian Macchi pilots were initially instructed to attack only damaged aircraft and stragglers from the main formation.[51]

The first confirmed air victory was claimed by Unteroffizier Leopold Hrastovcan on 24 April 1944, against a B-24 shot down near the village of Zapresic (Zagorje).[50] According to some sources, during these first sorties, Croat C.202s claimed 11 to 16 air victories, but only three more were confirmed. In May 1944, the Croatians received four C.202s from the Luftwaffe in Niš. During the ferry flight, one Macchi crash landed near Zemun airfield. The Croat unit received the last six Folgore and three or four brand new Macchi C.205s, around June 1944.[50][52] Even if the Croatian Air Force Legion was disbanded at the end of July, and replaced by the Croatian Air Force Group (HZS), the Macchi remained at Borovo.[50] During a period of intensive activity over the summer, the squadron claimed some 20 Allied aircraft shot down.[52] At the end of the summer, the C.202s still in flying conditions based in Borovo were used by Croatian cadets for training. In September 1944, Luftwaffe pilots flew all airworthy Folgore to Borongaj where they were used only for training.[50] Croatian pilots did not at first have a high opinion of the Macchi fighter, due to its armament of just two 12.7 mm and two 7.7mm machine guns, regarded as scarcely effective against the heavily armed US four-engined bombers.[51] Eastern front veteran Major Josip Helebrant, an 11-kill flying ace[53] (used to flying Bf 109Gs) and the CO of 2./(Kroat.)JGr, initially regarded the Macchis as "old, weary and unusable", and described the morale of his men as "low", and his unit's results as "nil", primarily because of the NDH's underdeveloped air-raid warning system, which saw the Croatian Macchi fighters often taking off to intercept attacking Allied bombers when they were already overhead.[51]

Folgore aces

The Macchi C.202 was flown by almost all the most successful Italian aces: Adriano Visconti, Luigi Gorrini, Franco Lucchini, Franco Bordoni Bisleri, Furio Niclot Doglio and top scorer Sergente Maggiore Teresio Vittorio Martinoli, credited with 22 individual "kills" plus two probables and 14 shared.[5] Seventeen of these victories were obtained in 73ª Squadriglia, 9° Gruppo (from 4° Stormo). Martinoli was killed during a training flight with the P-39 Airacobra on 25 August 1944. Capitano Franco Lucchini, credited with 21/26 individual victories and 52 shared, began to fly the Folgore after having shot down 10 enemy aircraft. He was killed in his C.202 on 5 July 1943 while attacking a B-17 over Gerbini, Sicily.[5]

Postwar service

Surviving aircraft were used by Aeronautica Militare Italiana as trainers until 1948.[2]

Variants and production

Like its predecessor C.200, the C.202 had relatively few modifications, with only 116 modifications during its career, most of them invisible, externally. The total series production ordered was 1,454: 900 to Breda, 150 to SAI Ambrosini, 403 to Aermacchi. The amount produced was actually 1,106 and not 1,220 as previous stated. Breda built 649 (Series XVI deleted, Series XII and XV partially completed caused the difference); Aermacchi made 390 examples, SAI only 67.[54]

One of the differences between prototype and series production was the lack of radio antenna and the retractable tailwheel (these differences resulting in a slightly higher top speed); the difference in speed was not so great and so, the series version had the fixed tailwheel and the radio antenna. The support for the engine, originally steel, was replaced with a lighter aluminium structure.[55]

- C.202

- Starting with the Serie VII, the fighter had a new wing with a provision for two 7.7 mm (.303 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns and an armored windscreen (previously, only the armored seat and the self-sealing tanks were provided). Serie IX's weight was 2,515/3,069 kg with the 7.7 machine guns seldom installed.[56]

- C.202AS

- Dust filters for operations in North Africa (AS – Africa Settentrionale, North Africa); they little affected the speed and so, almost all Folgores had them and thus were in C.202AS standard; finally, starting with Serie XI there was a provision for two 50, 100 or 160 kg bombs, small bombs clusters (10, 15, 20 kg) or 100 l drop tanks. These underwing pylons were rarely utilized, as Folgores were needed in the interceptor roles.[57]

- C.202CB

- Underwing hardpoints for bombs or drop tanks (CB – Caccia Bombardiere, Fighter-Bomber)

- C.202EC

- probably meaning Esperimento Cannoni, it was another link between Veltro and Folgore. One aircraft (Serie III, s/n MM 91974) was fitted with a pair of gondola-mounted 20 mm cannon with 200 rounds each (it flew on 12 May 1943); later it was turned into a C.205V. Another four examples were so equipped, but, despite the good results in the trials (aimed to boost the Folgore's firepower), there was no further production, because the cannons penalized the aircraft's performance. There was, in the Folgore, no room to mount them inside the wings or the nose, so the MC.205V/Ns was developed.[58] Nevertheless, the XII series could have introduced a new wing with MG 151 provisions. This is not well documented, as this series was produced by Breda after the Armistice, and was interrupted with the devastating USAAF bombings, together with many others aircraft; among them, also Macchi 205 production and the 206 prototype (30 April 1944; in five days, the USAAF destroyed both Fiat and Macchi facilities, eliminating all of Italy's fighter production).[59]

- C.202RF

- Equipped with cameras for photo-reconnaissance missions (R – Ricognizione, Reconnaissance), very few produced, later the recce role was covered by Veltros.[58]

- C.202D

- Prototype with a revised radiator, under the nose, similar to the P-40 (s/n. MM 7768)

- C.202 AR.4

- at least one was modified as "drone director" (coupled with S.79s), and it was planned to use Folgores also as 'Mistel', with an AR.4 "radiobomba" (a sort of remote-control kamikaze bomber).[56]

- C.202 with DB 605 and other engines

- Macchi MC.202 with DB 605 were initially known as MC.202 bis; later as the C.205 Veltro. Macchi C.200, C.202 and C.205 shared many common components. The MC.200A/2 was a MC.200 with Folgore wings (MM.8238). After the Armistice, Aeronautica Sannita or the Co-Belligerent Italian AF began MC.205 modifying C.202s with DB 605s. These aircraft were known also as Folgeltro. Around two dozen were made. Another Folgore was modified with DB 601E-1 (1,350 PS) in summer 1944, but this hybrid with Bf 109F technology crashed on 21 January 1946. The MC.204 was a version with a L.121 Asso (1,000 hp); proposed early in the war (28 September 1940), but all the effort continued only with DB 601 engines.[58] Early Folgores had original DB 601s, while from the Serie VII, RC.41s were available.

After the war, 31 C.202 airframes were fitted with license-built Daimler-Benz DB 605 engines and sold to Egypt as C.205 Veltros, with another 11 'real' MC.205s (with MG 151 cannons in the wings).

Operators

- Italian Air Force operated some Macchi C.202 until 1948[60]

Survivors

- Macchi C.202 "73-7/M.M. 9667 (serial no. 366)"

- Presently on display at the Italian Air Force Museum in Vigna di Valle Airport, near Bracciano, Italy. This C.202 was built by Breda in early 1943 as a Serie XI sample. In March 1943 this Folgore was assigned to 54° Stormo of the Regia Aeronautica and subsequently it served in 5° Stormo, with Aeronautica Cobelligerante (Italian Co-Belligerant Air Force). After the war it was a training aircraft at the Accademia Navale in Livorno. Currently the aircraft has the markings of the ace Giulio Reiner. Not all the parts of the aircraft are original (a panel of the engine cowling comes from a Macchi C.205 Veltro).[61]

- Macchi C.202 "M.M. 9476(?)"

- Shown in the markings of the 90ª Squadriglia, 10° Gruppo, 4° Stormo, is dramatically displayed in Gallery 205 above the World War II Aviation diorama at the US National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian, Washington, DC. Still airworthy at Freeman Field, Indiana, US, in 1945, as FE-300, was stored for many years. Restoration was completed in mid-1970. No identity marking was found, though this is the least reconstructed Folgore survivor. It may have originally been a Serie VI to IX, probably the M.M. 9476 sample.[61]

Specifications (C.202CB Serie IV-VIII)

General characteristics

- Crew: One

- Length: 8.85 m (29 ft 0.5 in)

- Wingspan: 10.58 m (34 ft 8.5 in)

- Height: 3.49 m (11 ft 5 in)

- Wing area: 16.82 m² (181.04 ft²)

- Empty weight: 2,491 kg (5,492 lb)

- Max. takeoff weight: 2,930 kg (6,460 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Alfa Romeo RA.1000 R.C.41-I Monsone liquid-cooled supercharged inverted V-12, 1,175 PS (864 kW) at 2,500 rpm for takeoff

Performance

- Maximum speed: 600 km/h (324 knots, 372 mph) at 5,600 m (18,370 ft)

- Range: 765 km (413 nm, 475 mi)

- Service ceiling: 11,500 m (37,730 ft)

- Rate of climb: 18.1 m/s (3,563 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 174.20kg/m² (35.68 lb/ft²)

- Power/mass: W/kg (hp/lb)

Armament

- 2 × 12.7 mm Breda-SAFAT machine guns in the engine cowling, 360/400 rpg

- 2 × 7.7 mm Breda-SAFAT machine guns in the wings, 500 rpg

- 2 × 50, 100, or 160 kg (110, 220, or 350 lb) bombs

- 2 × 100 L (26.4 US gal; 22.0 imp gal) drop tanks

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Curtiss P-40

- Kawasaki Ki-61

- Lavochkin-Gorbunov-Goudkov LaGG-3

- Messerschmitt Bf 109

- Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-1

- Supermarine Spitfire

- Related lists

References

- Notes

- ↑ Angelucci, Enzo (1988). Combat aircraft of World War II. p. 56. ISBN 0-517-64179-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Angelucci and Matricardi 1978, p. 219.

- 1 2 Mondey 2006, p. 155.

- 1 2 Matricardi 2006, pp. 70–71.

- 1 2 3 4 Sgarlato 1998, pp. 8–20.

- ↑ Winchester 2004, p. 172.

- ↑ Dunning 2000, p. 209.

- ↑ Duma 2007, pp. 232–233.

- ↑ Mondey 2006, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gentilli and Gorena 1980, p. 5.

- ↑ Note: MM. = Matricola Militare or Military Serial number.

- ↑ Caruana 1996, p. 175.

- ↑ Ciampaglia 1994, p. 79.

- ↑ Sgarlato 2005, p. 28.

- ↑ Sgarlato, Nico. Reggiane. Lu-August 2005, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Gentilli and Gorena 1980, pp. 5, 7.

- ↑ Marcon, Tullio. "P-40." Storia Militare, January 2001 p. 21, gives a ratio of 2.1 kg/hp for the Bf 109, 2.5 for the MC.202, 2.1 for the Spitfire VC and 3.3 for the P-40E.

- ↑ Ethell and Christy 1979, p. 51.

- ↑ Williams and Gustin 2003, p. 107.

- ↑ Massimello, Giorgio. La caccia italiana 1940–43, p. 11.

- ↑ Sgarlato 1998, p. 33.

- ↑ Ghergo 2006, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 Cattaneo 1971

- ↑ Duma 2007, p. 217.

- ↑ Malizia 2002, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Duma 2007, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ Duma 2007, p. 215.

- ↑ Ethell 1996, p. 69.

- ↑ De Marchi, Italo – Tonizzo, Pietro. Macchi MC. 200 / FIAT CR. 32. Modena, Edizioni Stem Mucchi 1994, p. 10.

- ↑ Borgiotti 1994, p. 3.

- ↑ Spick 1997, p. 117.

- ↑ Glancey 2007, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Duma 2007, p. 223.

- ↑ Malizia 2002, p. 95.

- ↑ Caruana 1999, p. 175.

- 1 2 Skulski 2012, p. 25.

- ↑ Caruana 1999, pp. 175–177.

- ↑ Shores et al. 1991, pp. 106–110.

- ↑ Beurling with Roberts 1943, pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Ethell 1995, p. 71.

- ↑ Massimello, Giorgio. "Il SAS e la R.A." Storia Militare, February 2008, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Massiniello 1996

- ↑ Neulen 2000, p. 63.

- 1 2 Bergström 2007, p. 98.

- ↑ De Marchi 1994, p. 10.

- ↑ Sgarlato, Macchi 202, p. 38.

- 1 2 Sgarlato 1998, p. 40.

- 1 2 Savic and Ciglic 2002

- ↑ Sgarlato 1998, pp. 41–45.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Skulski 2012, p. 57

- 1 2 3 Savic & Ciglic 2002, p. 63.

- 1 2 Savic and Ciglic 2002, p. 64.

- ↑ Savic and Ciglic 2002, p. 82.

- ↑ Sgarlato 2008

- ↑ Sgarlato Nico, Folgore Monography Feb 2008

- 1 2 Sgarlato 2008, p. 36.

- ↑ Sgarlato 2008, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 Sgarlato 2008, p. 37.

- ↑ Sgarlato Nico. I caccia Serie 5 Monography, March 2009, pp. 16, 30, 43.

- ↑ Official website Aeronautica Militare

- 1 2 Skulski 2012, p. 22.

- ↑ Green and Swanborough 2001

- Bibliography

- Angelucci, Enzo and Paolo Matricardi. World Aircraft: World War II, Volume I (Sampson Low Guides). Maidenhead, UK: Sampson Low, 1978. ISBN 978-0-528-88170-1.

- Bergström, Christer. Stalingrad—The Air Battle: 1942 through January 1943. Hinckley, UK: Midland, 2007. ISBN 978-1-85780-276-4.

- Beurling, George and Leslie Roberts. Malta Spitfire: The Story of a Fighter pilot. New York/Toronto: Farrar & Rinehart Inc., 1943. NO ISBN.

- Borgiotti, Alberto and Cesare Gori. Le Macchine e la Storia, Profili 1: Macchi MC 202 Folgore (in Italian). Modena, Italy: STEM-Mucchi, 1970. No ISBN.

- Caruana, Richard J. Victory in the Air. Malta: Modelaid International Publications, 1996. ISBN 1-871767-12-1.

- Cattaneo, Gianni. "The Macchi C.202." Aircraft in Profile no.28. Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Profile Publications, 1971.

- Ciampaglia, Giuseppe. "La Produzione Aeronautica nella II GM." (in Italian)." RID, May 1994.

- De Marchi, Italo and Pietro Tonizzo. Macchi MC. 200 / FIAT CR. 32 (in Italian). Modena, Italy: Edizioni Stem Mucchi 1994. NO ISBN.

- Duma, Antonio. Quelli del Cavallino Rampante – Storia del 4° Stormo Caccia Francesco Baracca (in Italian). Roma: Aeronautica Militare – Ufficio Storico, 2007. NO ISBN.

- Dunning, Chris. Solo coraggio! La storia completa della Regia Aeronautica dal 1940 al 1943 (in Italian). Parma, Italy: Delta Editrice, 2000. No ISBN.

- Ethell, Jeffrey L. Aircraft of World War II. Glasgow: HarperCollins/Jane’s, 1995. ISBN 0-00-470849-0.

- Ethell, Jeffrey L. and Joe Christy. P-40 Hawks at War. Shepperton, UK: Ian Allan Ltd, 1979. ISBN 0-7110-0983-X.

- Gentilli, Roberto and Luigi Gorena. Macchi C.202 In Action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1980. ISBN 0-89747-100-8.

- Ghergo, Federico. "La Caccia Italiana 1940–43" (in Italian). Storia Militare, February 2006.

- Glancey, Jonathan. Spitfire: The Illustrated Biography. London: Atlantic Books, 2008. ISBN 978-1-84354-528-6.

- Green, William. "The Macchi-Castoldi Series". Famous Fighters of the Second World War, vol.2. London: Macdonald, 1962. No ISBN.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Jackson, Robert. The Forgotten Aces. London: Sphere Books Ltd, 1989. ISBN 0-7474-0310-4.

- Malizia, Nicola. Aermacchi Bagliori di Guerra – Flashes of War (Macchi MC.200- MC.202 – MC.205/V) (in Italian). Rome: Ibn Editore, 2002. ISBN 88-7565-030-6.

- Malizia, Nicola. "L'armamento Dei Velivoli Della Regia Aereonautica" (in Italian). Storia Militare, Sebtembre 1997.

- Marcon, Tullio. "Hawker in Mediterraneo (in Italian)." Storia Militare N.80.

- Massiniello, Giorgio. "Lo Sviluppo del (Macchi) Veltro (in Italian)." Storia Militare, N.150.

- Massiniello, Giorgio. "Via da Korba, con ogni mezzo" (in Italian). Storia Militare 1996 (31). Parma, Italy: Ermanno Albertelli Ed.

- Mattioli, Mario. "L'esordio del Macchi C 202" (in Italian). Storia Militare, 1996. Parma, Italy: Ermanno Albertelli Ed.

- Matricardi, Paolo. Aerei Militari: Caccia e Ricognitori (in Italian). Milan, Italy: Mondadori Electa Editore, 2006.

- Mondey, David. The Hamlyn Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II. London: Bounty Books, 2006. ISBN 0-7537-1460-4.

- Neulen, Hans Werner. In the Skies of Europe. Ramsbury, Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press, 2000. ISBN 1-86126-799-1.

- Nijboer, Donald: "Spitfire V vs C.202 Folgore – Malta 1942 (Osprey Duel ; 60)". Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2014. ISBN 978-1-78200-356-4

- Nolan, Brian. Hero: The Buzz Beurling Story. London: Penguin Books, 1981. ISBN 0-14-006-266-1.

- Pesce, Giuseppe and Giovanni Massimello. Adriano Visconti Asso di Guerra (in Italian). Parma, Italy: Albertelli Edizioni speciali s.r.l., 1997.

- Rogers, Anthony: Battle over Malta: Aircraft Losses & Crash Sites 1940–42 London: Sutton Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0-7509-2392-X.

- Savic, Dragan and Boris Ciglic. Croatian Aces of World War II (Osprey Aircraft of the Aces-49). Oxford, UK: Oxford, 2002. ISBN 1-84176-435-3.

- Sgarlato, Nico. "Macchi Folgore" (in Italian). Aerei Nella Storia 1998 (8): 8–20. Parma, Italy: West-Ward sas.

- Sgarlato, Nico. "Macchi Folgore" (in Italian). Publisher unknown, 2008.

- Sgarlato Nico. "Reggiane fighters (Delta Editions)" (in Italian). Monography N.17, July 2005.

- Shores, Christopher, Brian Cull and Nicola Malizia. Malta: The Hurricane Years (1940–1941). London: Grub Street, 1987. ISBN 0-948817-06-2.

- Shores, Christopher, Brian Cull and Nicola Malizia. Malta: The Spitfire Year (1942). London: Grub Street, 1991. ISBN 0-948817-16-X.

- Skulski, Przemysław. Macchi C.202 Folgore(in English). Petersfield, Hampshire: Mushroom Model Publications, 2012. ISBN 978-83-614-21-66-5.

- Skulski, Przemysław. Macchi C.202 Folgore, seria "Pod Lupa" 7(in Polish). Wrocław, Poland: Ace Publications, 1997. ISBN 83-86153-55-5.

- Skulski, Przemysław. Macchi C.202 Folgore(in Polish). Sandomierz, Poland/Redbourn, UK: Stratus/Mushroom Model Publications, 2005. ISBN 83-89450-06-2.

- Snedden, Robert. World War II Combat Aircraft. Bristol, UK: Parragon, 1997. ISBN 0-7525-1684-1.

- Spick, Mike. Allied Fighter Aces of World War II. London: Greenhill Books, 1997. ISBN 1-85367-282-3.

- Williams, Anthony G. and Dr. Emmanuel Gustin. Flying Guns: World War II – Development of Aircraft Guns, Ammunition and Istallations 1933–1945. Ramsbury, Marlborough, UK: The Crowood Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1-84037-227-4.

- Winchester, Jim. "Macchi M.C.202 and M.C.205V." Aircraft of World War II: The Aviation Factfile. Kent, UK: Grange Books plc, 2004. ISBN 1-84013-639-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Macchi MC.202. |

- Commando Supremo. Italy at War

- Macchi: the fighters with the hunchback

- Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Macchi C.202 Folgore

- C. 202 Photofile (Italian)

| ||||||||||||||||||