Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art

| |

| Established | 1999 |

|---|---|

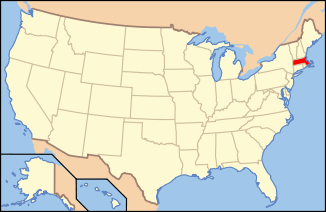

| Location | North Adams, Massachusetts |

| Director | Joseph C. Thompson |

| Website | www.massmoca.org |

|

Arnold Print Works | |

_3.jpg) | |

|

Buildings of the Arnold Print Works, now MASS MoCA, along a tributary of the Hoosic River (2012) | |

| |

| Location | 87 Marshall St., North Adams, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°42′5″N 73°6′59″W / 42.70139°N 73.11639°WCoordinates: 42°42′5″N 73°6′59″W / 42.70139°N 73.11639°W |

| Area | 24 acres (9.7 ha) |

| Built | 1872 |

| Architectural style | Italianate Industrial |

| MPS | North Adams MRA |

| NRHP Reference # | [1] |

| Added to NRHP | October 25, 1985 |

The Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) is a museum in a converted factory building complex located in North Adams, Massachusetts. It is one of the largest centers for contemporary visual art and performing arts in the United States. The complex was built by the Arnold Print Works, a business which operated on the site from 1860 to 1942, and was used by the Sprague Electric Company before its conversion.

MASS MoCA opened with 19 galleries and 100,000 sq ft (9,300 m2) of exhibition space in 1999. In addition to housing galleries and performing arts spaces, it also rents space to commercial tenants.[2] It is the home of the Bang on a Can Summer Institute, where composers and performers from around the world come to create and perform new music. The festival, started in 2001, includes concerts in galleries for three weeks during the summer. Starting in 2010, MASS MoCA has become the home for the Solid Sound Music Festival, curated by Wilco. The three-day-long festival takes place all over MASS MoCA's campus.

Museum location and history

Arnold Print Works

The buildings that MASS MoCA now occupies were originally built between 1870 and 1900 by the company Arnold Print Works. These buildings, however, were not the first to occupy this site. Since colonial times small-scale industries had been located on this strategic peninsular location between the north and south branches of the Hoosic River. In 1860 the Arnold brothers arrived at this site and set up their company with the latest equipment for printing cloth. They began operating in 1862 and quickly took off. Aiding their success were large government contracts during the Civil War to supply cloth for the Union Army.[3]

In December 1871, a fire swept through the Arnold Print Works factory and destroyed eight of its buildings. Rebuilding started almost immediately and an expanded complex was finished in 1874. Despite a nationwide depression during the 1870s Arnold Print Works purchased additional land along the Hoosic River and constructed new buildings. By 1900, every building but one in today's Marshall Street complex was constructed.[3]

_5.jpg)

At its peak in 1905, Arnold print works employed more than 3,000 workers and was one of the world's leading producers of printed textiles. Arnold produced 580,000 yards or 330 miles of cloth per week. Arnold had offices in New York City and Paris. In addition to printing the textiles, Arnold Print Works expanded and built their own cloth-weaving facilities in order to produce "grey cloth", which was the crude, unfinished textile from which printed color cloth was made.[4]

In 1942 Arnold Print Works was forced to close its doors and leave North Adams due to the low prices of cloth produced in the South and abroad, as well as the economic effects of the Great Depression.

Sprague Electric Company

Robert C. Sprague's (son of Frank J. Sprague) Sprague Electric Company was a local North Adams company, and it purchased the Marshall Street complex to produce capacitors. During World War II Sprague operated around the clock and employed a large female workforce—not only due to the lack of men, but also because it took small hands and manual dexterity to construct the small, hand-rolled capacitors. In addition to manufacturing electrical components, Sprague had a large research and development department.[5] This department was responsible for research, design, and manufacturing of the trigger for the atomic bomb and components used in the launch systems for the Gemini moon missions.

At its peak during the 1960s Sprague employed 4,137 workers in a community of 18,000. Essentially the factory was a small city within a city with employees working alongside friends, neighbors and relatives. The company was almost completely self-sufficient, holding a radio station, orchestra, vocational school, research library, day-care center, clinic, cooperative grocery store, sports teams, and a gun club with a shooting range on the campus.

In the 1980s Sprague began to face difficulties with global changes in the electronics industry. Cheaper electronic components were being produced in Asia combined with changes in high-tech electronics forced Sprague to sell and shutdown its factory in 1985. As a result, North Adams was left "deindustrialized" and found itself on a steep economic decline.[6]

The site was formerly listed as a superfund contaminated site.[7] The complex was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.[1][8]

MASS MoCA

The development of MASS MoCA began a year after Sprague vacated the buildings. In 1986 a group of staff from the nearby Williams College Museum of Art were looking for large factory or mill buildings where they could display and exhibit large works of modern and contemporary art that they weren't able to display in their more traditional museum/gallery setting. They were directed to the Marshall Street complex by the mayor of North Adams. When they spent time with the space, they quickly realized the buildings had much more potential than an offshoot gallery. The process for MASS MoCA began.

It took a number of years of fund-raising and organization to develop MASS MoCA. During this process the project evolved to create not only new museum/gallery space but also a performing arts venue. The transformation was chronicled by photographer Nicholas Whitman's Mass MoCA: From Mill to Museum.[9] The museum was granted $18.6 million by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts after a public/private coalition petitioned the state government to support the project.[10] In 1999 MASS MoCA opened its doors.

Designed by the Cambridge architecture firm of Bruner Cott & Assoc, it was awarded highest honors by the American Institute of Architects and The National Trust for Historic Preservation.[11]

Ongoing exhibitions

Sol LeWitt Wall Drawing Retrospective Exhibition

On November 16, 2008, the museum opened an exhibition of Sol LeWitt wall drawings in partnership with Yale University Art Gallery and Williams College Museum of Art. The exhibition, Sol LeWitt: A Wall Drawing Retrospective occupies a 27,000-square-foot (2,500 m2) building located at the center of the campus. More than 100 monumental wall drawings and paints conceived by the artist from 1968-2007 will be on view through 2033. Cambridge-based Bruner/Cott & Associates converted the historic mill building and worked with LeWitt to design the gallery space. LeWitt designed the final placement of the drawings before his death in April 2007, and the drawings were installed by a team of draftsmen between April 1 and September 30, 2008.[12] The exhibition was chosen as the "top museum exhibition of 2008" by Time Magazine.[13]

Anselm Kiefer

A collaboration with the Hall Art Foundation, this presentation of work by German painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer consists of three monumentally scaled installations, Etroits Sont Les Vaisseaux, Les Femmes De La Revolution, and Velimir Chlebnikov, and occupies a 10,000 square foot building renovated for the exhibition. On view Spring/Summer/Fall through 2028.[14]

Natalie Jeremijenko

Tree Logic. Installed in the museum's front courtyard, this project displays the slow yet dynamic changes of six live trees, inverted and suspended from a truss, over time.

Landscapes Seen & Imagined

A midcareer survey of Clifford Ross's experiments with realism and abstraction. In addition to photographic works, the exhibition includes a 24’ high x 114’ long photograph on raw wood that spans the length of the museums tallest gallery and a 10' high x 30' long wall of LEDs, which simulate the action of waves.[15] On view through March 2016.

Gallery 4.1.1

Liz Deschenes. Installation maintained through April 2016.

An Expanded Field of Photography

Dana Hoey. Craig Kalpakjian. Miranda Lichtenstein. Josh Tonsfeldt. Sara VanDerBeek. Randy West. On view through April 2016.

Encampment

A multi-part installation by Italian artist Francesco Clemente, this suite of six painted canvas tents, executed in collaboration with artists in Rajasthan, India conjures associations with geographic nomadism and existential flux. On view through January 2016.[16]

Entertaining Doubts

A survey of recent work by American artist Jim Shaw. A contemporary of Mike Kelley, Shaw's work also explores themes of the American subconscious through comic books, conspiracy theories, puns and dreams. On view through January 2016.

Past exhibitions

Invisible Cities

Titled after an Italo Calvino book, the exhibition featured the work of ten artists who reimagine urban landscapes both familiar and fantastical. Invisible Cities includes works by Lee Bul, Carlos Garaicoa, and Sopheap Pich, as well as commissions by Diana Al Hadid, Francesco Simeti, Miha Strukelj, and local artists Kim Faler and Mary Lum.

Oh, Canada

The largest survey of contemporary Canadian art ever produced outside Canada, "Oh, Canada" features work by more than 60 artists from every Canadian province and nearly every Canadian territory, spanning multiple generations and working in many media.

Notable participating artists:

Katharina Grosse

One Floor Up More Highly. Katharina Grosse applied paint to four mounds of soil which seemed to spill from the upper balcony into the enormous space below. Stacks of styrofoam shards rose out of the mountains of color, mirroring the white of the gallery walls.

Petah Coyne

Everything That Rises Must Converge. Baroque style pieces were displayed in four galleries on MASS MoCA's main floor. One piece, "Scalapino/Nu Shu", came upon the viewer as a former apple-bearing tree. Coyne had it uprooted and brought to the museum after it stopped bearing fruit. Petah's exhibit also includes a selection of her photography.

Sean Foley

Ruse. Sean Foley's commissioned work for MASS MoCA occupied the over-100-foot-long wall outside of the Hunter Center for the Performing Arts.

Jörg Immendorff

Student of Beuys, 6 paintings. Jörg Immendorff was one of several prominent artists of the past four decades who studied under Joseph Beuys at the Düsseldorf Academy of Art. This exhibition was the second in an occasional series of shows focused on Beuys and those influenced by his work and teaching.

Jenny Holzer Projections

On November 18, 2007, Jenny Holzer presented her first indoor projection in the United States. Holzer's projection at Mass MoCA filled a large chamber first with selected poems by Nobel laureate Wisława Szymborska, and later with selections from prose by Nobel laureate Elfriede Jelinek.

Badlands: New Horizons in Landscape

"Badlands" (May 24, 2008 - April 12, 2009) was an exhibition of environmental art that explored contemporary artists’ fascination with the Earth and their responses to environmental concerns. Works were commissioned for the exhibit from Vaughn Bell, the Center for Land Use Interpretation, Nina Katchadourian, Joseph Smolinski and Mary Temple. Other artists exhibiting included Robert Adams, the Boyle Family, Melissa Brown, Leila Daw, Gregory Euclide, J. Henry Fair, Mike Glier, Anthony Goicolea, Marine Hugonnier, Paul Jacobsen, Mitchell Joachim, Jane Marsching, Alexis Rockman, Edward Ruscha, Yutaka Sone and Jennifer Steinkamp.[17][18]

Simon Starling

Simon Starling's The Nanjing Particles opened in December 2008. Based on small stereoscopic photograph depicting a large group of Chinese workers in front of Sampson Shoe Factory. Sampson had brought them east from California to break a strike. As a result, North Adams had the largest population of Chinese workers this side of the Mississippi. He viewed the stereograph image underneath a one-million-volt electron microscope, allowing him to see individual metal particles that comprise the photograph and allowing that to propel him towards the creation of two large-scale sculptures that were manufactured by hand in Nanjing, China.

Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle

Opening in December 2009, Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle's Gravity is a Force to be Reckoned With opened with an upside-down Mies van der Rohe glass house in MASS MoCA's large Building 5 gallery space. The architecture of the house comes from plans made by Mies van der Rohe for his house with four columns or the 50x50 house (1951), that was never realized. Within the house, whose furniture defy gravity sitting firmly on the floor that is the ceiling, there is evidence of an occupant who has been up to something. Accompanying the house is a film, titled Always After (The Glass House) (2006).

The Knitting Machine

On June 30, 2005, MASS MoCA presented an American sculptural installation by Dave Cole, who was in residence at MASS MoCA with his project The Knitting Machine which comprised two excavators specially fitted with massive 20' knitting needles. The knitting project was expected to be completed by July 3. The product, "The Knitting Machine", is an oversized American flag.

When the flag was removed from "The Knitting Machine" it was folded into the traditional flag triangle and was on display in a presentation case which Cole described as "slightly smaller than a Volkswagen Beetle", accompanied by the 20' knitting needles and a video of the knitting process.

Material World

Sculpture to Environment. Working in a range of industrially produced materials—from plastic sheeting to fishing line—Michael Beutler, Orly Genger, Tobias Putrih, Alyson Shotz, Dan Steinhilber, and collaborators Wade Kavanaugh and Stephen B. Nguyen engage the former factory spaces of the museum's second and third floors, creating extraordinary environments from ordinary things.

Leonard Nimoy

Secret Selves. Artist/actor Leonard Nimoy exhibited a recent photographic series. Shooting in nearby Northampton, Massachusetts, Nimoy recruited volunteers from the community with an open call for portrait models willing to be photographed posed and dressed as their true or imagined "secret selves". Accompanying the large, life-size photographs is a video documenting the artist's conversations with his subjects.

Past Building 5 exhibitions

Past exhibitors in Building 5 include Robert Rauschenberg, Tim Hawkinson, Robert Wilson, Ann Hamilton, Cai Guo-Qiang, Carsten Höller, Sanford Biggers, and Xu Bing.

Christoph Büchel's installation

In May 2007, the museum became embroiled in a legal dispute with Swiss installation artist Christoph Büchel. The museum had commissioned Büchel to create a massive installation, "Training Ground for Democracy", the exhibit was to include a rebuilt movie theater, nine shipping containers, a full-size Cape Cod-style house, a mobile home, a bus, and a truck.[19] On On May 21, 2007, MASS MoCA filed a one-count complaint in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts, seeking permission from Judge Michael A. Ponsor that the museum was entitled to present to the public Büchel's art installation without the artist's consent.[20]

Büchel claimed that allowing the public to view it in an unfinished state and without his permission would misrepresent his work, infringe his copyrights, and infringe his moral rights granted under U.S. law, specifically, the 1990 Visual Artists Rights Act.[21] Contrary to Büchel's allegation, the museum alleged thatBüchel did not respond to requests by the museum to come and remove the materials.[22] On September 21, 2007, Judge Michael Ponsor of the Federal District Court for Massachusetts in Springfield ruled that there was no copyright violations and no distortion inherent in showing an unfinished work as long as it was clearly labeled as such. Judge Ponsor noted that his opinion would likely not be viewed as creating a legal precedent. Although the museum was granted permission to exhibit Büchel's art installation without his consent, it chose not to do so.

Büchel appealed the district court's ruling, and in January of 2010 the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit overruled Judge Ponsor, hiding that the 1990 Visual Artists Rights Act applies to unfinished works of art, and that Büchel asserted a viable claim under the Copyright Act that MASS MoCA violated his exclusive right to display his work publicly.[23]

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 Staff (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Dobrzynski, Judith H. (May 30, 1999). "Massachusetts Home for Contemporary Art". NYTimes.com (New York Times). Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- 1 2 Trainer, p. 9

- ↑ Trainer, p. 10

- ↑ Trainer, p. 11

- ↑ Trainer, p.11

- ↑ "Massachusetts Superfund Sites"

- ↑ "Press Release: Site History". Mass MoCA. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ↑ http://www.amazon.com/Mass-MoCA-Museum-Nicholas-Whitman/dp/0970073801/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1372730952&sr=1-2

- ↑ Trainer, p. 12

- ↑ "Bruner/Cott Award". brunercott.com. Archived from the original on 2007-06-18. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

|first1=missing|last1=in Authors list (help) - ↑ Smee, Sebastian (November 16, 2008). "In vast LeWitt show, absurdity and beauty". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ↑ Lacayo, Richard (November 3, 2008). "Sol LeWitt: A Wall Drawing Retrospective". 2008 Top Ten Museum Exhibits (Time Magazine). Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- ↑ http://www.massmoca.org/event_details.php?id=848

- ↑ http://www.cliffordross.com/exhibitions/landscape-seen-and-imagined/installations

- ↑ http://www.massmoca.org/event_details.php?id=999

- ↑ "Badlands: New Horizons in Landscape". MASS MoCA (Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art). 2008-05-24. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ Markonish, Denise. "Badlands". MIT Press. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Roberta (September 16, 2007). "Is It Art Yet? And Who Decides?". NYTimes.com (New York Times). Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ↑ "MassMOCA v Buchel District Court Opinion". Scribd. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ "MassMOCA v Buchel District Court Opinion". Scribd. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

- ↑ Johnson, Ken (July 1, 2007). "No admittance: Mass MoCA has mishandled disputed art installation". Boston.com. Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ↑ "Mass MoCA v. Christoph Büchel, First Circuit Opinion". Scribd. Retrieved 2015-12-12.

Bibliography

- Trainer, Jennifer ed. Whitman, Nicholas photographer, MASS MoCA: From Mill to Museum. North Adams:MASS MoCA Publications, 2000.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to MASS MoCA. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||