Scott Carpenter

| Malcolm Scott Carpenter | |

|---|---|

| |

| NASA Astronaut | |

| Nationality | American |

| Status | Deceased |

| Born |

Malcolm Scott Carpenter May 1, 1925 Boulder, Colorado, U.S. |

| Died |

October 10, 2013 (aged 88) Denver, Colorado, U.S. |

Other occupation | Naval aviator, test pilot, aquanaut (SEALAB II) |

| University of Colorado, B.S. 1962 | |

| Rank | Commander, USN[1] |

Time in space | 4 hours 56 minutes |

| Selection | 1959 NASA Group 1 |

| Missions | Mercury-Atlas 7 |

Mission insignia |

|

| Retirement | August 10, 1967 |

| Awards |

|

Malcolm Scott Carpenter (May 1, 1925 – October 10, 2013), (Cmdr, USN), was an American naval officer and aviator, test pilot, aeronautical engineer, astronaut, and aquanaut. He was one of the original seven astronauts selected for NASA's Project Mercury in April 1959. Carpenter was the second American (after John Glenn) to orbit the Earth and the fourth American in space, following Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom, and John Glenn. His death on October 10, 2013 leaves Glenn as the last surviving Mercury 7 member.

Early life

Born May 1, 1925, in Boulder, Colorado, Carpenter moved to New York City with his parents Marion Scott Carpenter and Florence (née Noxon) Carpenter for the first two years of his life. His father had been awarded a postdoctoral research post at Columbia University. In the summer of 1927, Scott returned to Boulder with his mother, then ill with tuberculosis. He was raised by his maternal grandparents in the family home at the corner of Aurora Avenue and Seventh Street, until his graduation from Boulder High School in 1943.[2] It was claimed that Carpenter named his spacecraft "Aurora 7" after Aurora Avenue, but he denied this.[3]

He was a Boy Scout and earned the rank of Second Class Scout.[4]

Naval service

Upon graduation, he was accepted into the V-12 Navy College Training Program as an aviation cadet (V-12a), where he trained until the end of World War II. The war ended before he was able to finish training and receive an overseas assignment, so the Navy released him from active duty. He returned to Boulder in November 1945 to study Aeronautical Engineering at the University of Colorado at Boulder. While at Colorado he joined Delta Tau Delta International Fraternity.[5] At the end of his senior year, he missed the final examination in heat transfer, leaving him one requirement short of a degree. After his Mercury flight, the university granted him a Bachelor of Science degree on grounds that, "His subsequent training as an Astronaut has more than made up for the deficiency in the subject of heat transfer."[2][6]

On the eve of the Korean War, Carpenter was recruited by the United States Navy's Direct Procurement Program (DPP). He reported to Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida in the fall of 1949 for pre-flight and primary flight training. He earned his aviator wings on April 19, 1951, in Corpus Christi, Texas. During his first tour of duty, on his first deployment, Carpenter flew Lockheed P2V Neptunes for Patrol Squadron Six (VP-6) on reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare (ASW) missions during the Korean War. Forward-based in Adak, Alaska, Carpenter then flew surveillance missions along the Soviet and Chinese coasts during his second deployment; designated as PPC (patrol plane commander) for his third deployment, LTJG Carpenter was based with his squadron in Guam.[2]

Carpenter was then appointed to the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School, class 13, at NAS Patuxent River, Maryland in 1954. He continued at Patuxent until 1957, working as a test pilot in the Electronics Test Division; his next tour of duty was spent in Monterey, California, at the Navy Line School. After attending the Naval Air Intelligence School, Washington D.C., for an additional eight months in 1957 and 1958, Carpenter was named Air Intelligence Officer for USS Hornet.[2]

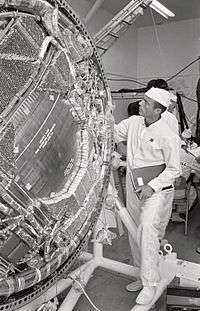

NASA career

After being chosen for Project Mercury in 1959, Carpenter, along with the other six astronauts, oversaw the development of the Mercury capsule. He served as backup pilot for John Glenn, who flew the first U.S. orbital mission aboard Friendship 7 in February 1962. Carpenter, serving as capsule communicator on this flight, can be heard saying "Godspeed, John Glenn" on the recording of Glenn's liftoff.

When Deke Slayton was withdrawn on medical grounds from Project Mercury's second manned orbital flight (which Slayton would have named Delta 7), Carpenter was assigned to replace him. He flew into space on May 24, 1962, atop the Mercury-Atlas 7 rocket for a three-orbit science mission that lasted nearly five hours. His Aurora 7 spacecraft attained a maximum altitude of 164 miles (264 km) and an orbital velocity of 17,532 miles per hour (28,215 km/h).[2]

Carpenter performed five onboard experiments per the flight plan, and became the first American astronaut to eat solid food in space. He also identified the mysterious "fireflies" observed by Glenn during Friendship 7 as particles of frozen liquid loosened from the outside of the spacecraft, which he could produce by rapping on the wall near the window. He renamed them "frostflies".[2]

Carpenter's performance in space was the subject of criticism and controversy. While one source has Christopher C. Kraft, Jr., directing the flight from Cape Canaveral, considering Carpenter's "mission the most successful to date; everything had gone perfectly except for some overexpenditure of fuel."[7] The New York Times reported in its obituary for Carpenter that Kraft was angry because Carpenter was not paying attention to his instruments and ignoring instructions from Mission Control. Kraft opposed Carpenter's assignment to future space missions.[8]

Unnoticed by ground control or pilot, however, this "overexpenditure of fuel" was caused by an intermittently malfunctioning pitch horizon scanner (PHS) that later malfunctioned at reentry. Still, NASA later reported that Carpenter had:

"exercised his manual controls with ease in a number of [required] spacecraft maneuvers and had made numerous and valuable observations in the interest of space science. ... By the time he drifted near Hawaii on the third pass, Carpenter had successfully maintained more than 40 percent of his fuel in both the automatic and the manual tanks. According to mission rules, this ought to be quite enough hydrogen peroxide, reckoned Kraft, to thrust the capsule into the retrofire attitude, hold it, and then to reenter the atmosphere using either the automatic or the manual control system."[7]

At the retrofire event, the pitch horizon scanner malfunctioned once more, forcing Carpenter to manually control his reentry, which caused him to overshoot the planned splashdown point by 250 mi (400 km). ("The malfunction of the pitch horizon scanner circuit [a component of the automatic control system] dictated that the pilot manually control the spacecraft attitudes during this event."[9]) The PHS malfunction jerked the spacecraft off in yaw by 25 degrees to the right, accounting for 170 miles (270 km) of the overshoot; the delay caused by the automatic sequencer required Carpenter to fire the retrorockets manually. This effort took two pushes of the override button and accounted for another 15 to 20 miles (30 km) of the overshoot. The loss of thrust in the ripple pattern of the retros added another 60 miles (100 km), producing a 250-mile (400 km) overshoot.[2]

During reentry, there was a great deal of concern over whether Carpenter had actually survived, since he splashed down 250 miles off course. Forty minutes after splashdown, Carpenter was located in his life raft, safe and in good health by Maj. Fred Brown under the command of the Puerto Rico Air National Guard,[10] and recovered three hours later by the USS Intrepid.[2]

Postflight analysis described the PHS malfunction as "mission critical" but noted that the pilot "adequately compensated" for "this anomaly ... in subsequent inflight procedures",[11] confirming that backup systems—human pilots—could succeed when automatic systems fail.[12]

Some memoirs[13][14] have revived the simmering controversy over who or what, exactly, was to blame for the overshoot, suggesting, for example, that Carpenter was distracted by the science and engineering experiments dictated by the flight plan and by the well-reported fireflies phenomenon. Yet fuel consumption and other aspects of the vehicle operation were, during Project Mercury, as much, if not more, the responsibility of the ground controllers. Moreover, hardware malfunctions went unidentified, while organizational tensions between the astronaut office and the flight controller office—tensions that NASA did not resolve until the later Gemini and Apollo programs—may account for much of the latter-day criticism of Carpenter's performance during his flight.[2]

Carpenter never flew another mission in space. After taking a leave of absence from the astronaut corps in the fall of 1963 to train for and participate in the Navy's SEALAB program, Carpenter sustained a medically grounding injury to his left arm in a motorbike accident. After failing to regain mobility in his arm after two surgical interventions (in 1964 and 1967), Carpenter was ruled ineligible for spaceflight. He resigned from NASA in August 1967.[2] He spent the last part of his NASA career developing underwater training to help astronauts with future spacewalks.

Ocean research

In July 1964 in Bermuda, Carpenter sustained a grounding injury from a motorbike accident while on leave from NASA to train for the Navy's SEALAB project.[2] In 1965, for SEALAB II, he spent 28 days living on the ocean floor off the coast of California.[15][16] During the SEALAB II mission, Carpenter's right index finger was wounded by the toxic spines of a scorpion fish.[17][18] He returned to work at NASA as Executive Assistant to the Director of the Manned Spacecraft Center, then returned to the Navy's Deep Submergence Systems Project in 1967, based in Bethesda, Maryland, as a Director of Aquanaut Operations for SEALAB III.[15][16]

In the aftermath of aquanaut Berry L. Cannon's death while attempting to repair a leak in SEALAB III, Carpenter volunteered to dive down to SEALAB and help return it to the surface, although SEALAB was ultimately salvaged in a less hazardous way.[19]

Carpenter retired from the Navy in 1969, after which he founded Sea Sciences, Inc., a corporation for developing programs for utilizing ocean resources and improving environmental health.[2]

Personal life

Carpenter was married four times, divorced three times, and had a total of seven children by three wives.

Carpenter married his first wife Rene Louise Price (born 1928) in 1948. They had four children: Marc Scott (deceased), Kristen Elaine, Candace Noxon, and Robyn Jay. By 1968, Carpenter and his wife had separated, with him living in California and Rene Carpenter having moved with their children to Washington, D.C. The Carpenters divorced in 1972.[20]

In 1972, Carpenter married his second wife Maria Roach, daughter of film producer Hal Roach. Together, they had two children: Matthew Scott and Nicholas Andre, who would later become a filmmaker.

In 1988, Carpenter married his third wife, Barbara Curtin. Their marriage produced a son, Zachary Scott, when Carpenter was in his 60s. The marriage ended in divorce a few years later.

In 1999, Carpenter married his fourth wife Patty Barrett, when he was 74. They resided in Vail, Colorado.[21]

In September 2013, Carpenter suffered a stroke and, after hospitalization, was admitted to the Denver Hospice Inpatient Care Center. He died on October 10, 2013 at the age of 88. Carpenter was survived by his wife at the time of his death, six children, a granddaughter, and five step-grandchildren.[22]

Awards and honors

Carpenter received:

- Navy Astronaut Wings

- Navy's Legion of Merit

- Distinguished Flying Cross

- NASA Distinguished Service Medal

- University of Colorado Recognition Medal

- Collier Trophy

- John J. Montgomery Award

- New York City Gold Medal of Honor

- Elisha Kent Kane Medal

- Ustica Gold Trident

- Boy Scouts of America Silver Buffalo Award

- Academy of Underwater Arts & Sciences 1995 NOGI Award for Distinguished Service

In 1962, Boulder community leaders dedicated Scott Carpenter Park and Pool in honor of native son turned Mercury astronaut. The Aurora 7 Elementary School, also in Boulder, was named for Carpenter's spacecraft.[2][23] Scott Carpenter Middle School in Westminster, Colorado, was named in his honor,[24] as was M. Scott Carpenter Elementary School in Old Bridge, New Jersey.[2][25]

The Scott Carpenter Space Analog Station was placed on the ocean floor in 1997 and 1998. It was named in honor of his SEALAB work in the 1960s.[26]

In popular culture

Speaking from the blockhouse at the launch of Friendship 7, Carpenter, John Glenn's backup pilot, said "Godspeed, John Glenn," as Glenn's vehicle rose off the launch pad to begin his first U.S. orbital mission on February 20, 1962.[2] This quote was included in the voiceovers of the teaser trailer for the 2009 Star Trek film.[27] The audio phrase is used in Kenny G's "Auld Lang Syne" (The Millennium Mix).[28] It is also used as a part of an audio introduction for the Ian Brown song "My Star".[29]

Carpenter has been reported also to have said, prior to the "Godspeed" comment, "Remember, John, this was built by the low bidder".[30] This comment is sometimes improperly attributed to Glenn.[31]

In the 1983 film, The Right Stuff, Carpenter was played by Charles Frank. Although his appearance was relatively minor, the film played up Carpenter's friendship with John Glenn, as played by Ed Harris. This film is based on the book of the same name by Tom Wolfe.[32]

The character of Scott Tracy in the Thunderbirds television series was named after Carpenter.[33]

Carpenter's recovery from the ocean following his space flight is referred to in the Peanuts comic strip of June 28, 1962, after Linus' security blanket is rescued.[34][35][36]

In the 2015 ABC TV series The Astronaut Wives Club, Scott Carpenter is portrayed by Wilson Bethel, and Rene Carpenter is portrayed by Yvonne Strahovski.

Physical description

- Weight: 160 lb (73 kg)

- Height: 5 ft 10 in (1.78 m)

- Hair: Brown

- Eyes: Green[37]

Books

- We Seven: By the Astronauts Themselves, ISBN 978-1439181034, by M. Scott Carpenter (Author), L. Gordon Cooper (Author), John H. Glenn (Author), Virgil I. Grissom (Author), Walter M. Schirra (Author), Alan B. Shepard (Author), Donald K. Slayton (Author),

- For Spacious Skies: The Uncommon Journey of a Mercury Astronaut, ISBN 0-15-100467-6 or the revised paperback edition ISBN 0-451-21105-7, Carpenter's biography, co-written with his daughter Kris Stoever; describes his childhood, his experiences as a naval aviator, a Mercury astronaut, including an account of what went wrong, and right, on the flight of Aurora 7.

- Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961–1965, by Francis French and Colin Burgess, 2007. A Carpenter-approved account of his life and space flight.

- The Steel Albatross, ISBN 978-0831776084. Science fiction. A "technothriller" set around the life of a fighter pilot in the US Navy's Top Gun school.

- Deep Flight, ISBN 978-0671759032. Science fiction. This follow-on to The Steel Albatross is an underwater outburst of war and action.

See also

References

- ↑ 40th Anniversary of the Mercury 7 Retrieved August 29, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Carpenter, Scott; Stoever, Kris (2003). For Spacious Skies: The Uncommon Journey Of A Mercury Astronaut. NAL Trade. pp. 384 pages. ISBN 978-0-451-21105-7. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ↑ Scott Carpenter JSC Oral History 1999 on YouTube

- ↑ M. Scott Carpenter at scouting.org

- ↑ Retrieved 2012-02-19

- ↑ For Spacious Skies, (hardcover ed.), p. 97.

- 1 2 This New Ocean, p. 453.

- ↑ "Scott Carpenter, One of the Original Seven Astronauts, Is Dead at 88". New York Times. October 10, 2013.

- ↑ Results of the Second United States Manned Orbital Spaceflight, NASA SP-6, p. 66.

- ↑ Sgt. Ramon Alonso, ed., Puerto Rico Air National Guard: Forty Five Years of History, 1947–1992. Centro Grafico del Caribe Inc., 1993.

- ↑ Results of the Second United States Manned Orbital Spaceflight, NASA SP-6, p. 1.

- ↑ "Flight of Aurora 7". Retrieved September 12, 2005.

- ↑ Eugene Cernan; Don Davis (1999). The Last Man on the Moon. St. Martins Press. pp. 51–52. ISBN 0-312-19906-6.

Scott Carpenter went up on Aurora 7, but didn't pay close enough attention to business and overshot his landing area, a mistake that cost him any future ride in space.

pg. 65 has “Scott was the only multi-engine pilot among the elite cadre of veteran jet pilots, and it was whispered that he didn’t volunteer for the space program, his dynamic and attractive wife did. Scott was just glad to be around, and was physically fit to an amazing degree. But he screwed up his own Mercury flight by joyriding, not paying enough attention to the job, missing his retrofire cue and splashing down several hundred miles from the target area. It became pretty obvious that Scott would never fly in space again.” - ↑ Chris Kraft, Flight: My Life in Mission Control (New York: Dutton, 2001).

- 1 2 Radloff, Roland and Helmreich, Robert (1968). Groups Under Stress: Psychological Research in Sealab II. Appleton-Century-Crofts. ISBN 0-89197-191-2.

- 1 2 Clarke TA, Flechsig AO, Grigg RW (September 1967). "Ecological studies during Project Sealab II. A sand-bottom community at depth of 61 meters and the fauna attracted to "Sealab II" are investigated". Science 157 (3795): 1381–9. Bibcode:1967Sci...157.1381C. doi:10.1126/science.157.3795.1381. PMID 4382569. Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ↑ MacInnis, Joseph B. (July 30, 1966). "The Medical and Human Performance Problems of Living Under the Sea" (PDF). The Canadian Medical Association Journal (Canadian Medical Association) 95 (5): 191–200. PMC 1936772. PMID 4380341. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ↑ Hellwarth, Ben (2012). Sealab: America's Forgotten Quest to Live and Work on the Ocean Floor. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-0-7432-4745-0. LCCN 2011015725.

- ↑ Craven, John Piña (2001). The Silent War: The Cold War Battle Beneath the Sea. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-87213-7.

- ↑ Martha Fay (April 7, 1975). "Ex-Astronaut Wife Rene Is the Carpenter in the News Now". People Magazine. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ↑ "Scott Carpenter Fast Facts". CNN NewSource. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Scott Carpenter Obituary". Legacy.com. October 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ↑ "History of Scott Carpenter Park and Pool". City of Boulder Colorado. City of Boulder. 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ Scott Carpenter Middle School

- ↑ M. Scott Carpenter Elementary School

- ↑ Chamberland, Dennis (2006). "Scott Carpenter Space Analog Station". The Challenge Project. NASA. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ Anthony Pascale (January 19, 2008). "Interview – Orci Answers Questions About New Star Trek Trailer". TrekMovie. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ Kenny G (1999). "Auld Lan Syne (The Millennium Mix) Lyric". Faith: A Holiday Album. EMI Music Publishing, Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, Warner/Chappell Music, Inc. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ Audio file on YouTube.

- ↑ "NASA veterans honour John Glenn's flight - World - CBC News". Cbc.ca. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ "John Glenn Polemic". snopes.com. Retrieved October 10, 2013.

- ↑ Wolfe, Tom. The Right Stuff. New York: Bantam, 2001. ISBN 0-553-38135-0.

- ↑ Marriott, John; Anderson, Gerry (foreword) (1992). Thunderbirds ARE GO! London: Boxtree. ISBN 1-85283-164-2. Page 18.

- ↑ Schulz, Charles M. (2009). "The Complete Peanuts: 1961–1962". Read About Comics web page. Fantagraphics Books. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ↑ Peanuts Comic Strip, June 28, 1962 on GoComics.com

- ↑ http://www.gocomics.com/peanuts/1962/06/28

- ↑ Scott Carpenter's physical description

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scott Carpenter. |

- Official website of Scott Carpenter

- Carpenter's official NASA long biography

- Carpenter's official NASA short biography

- Astronautix biography of Scott Carpenter

- Spacefacts biography of Scott Carpenter

- Carpenter at Encyclopedia of Science

- About Scott Carpenter

- Carpenter at Spaceacts

- Iven C. Kincheloe Awards

- Scott Carpenter at the Internet Movie Database

- Carpenter at International Space Hall of Fame

- NYTimes obituary

- Carpenter, Rene (June 1, 1962). "The Time That Grew Too Long". Life Magazine. p. 26-37. Retrieved August 2, 2015. Rene Carpenter's article for Life magazine on Carpenter's flight.

- Scott Carpenter at Find a Grave

|