M-estimator

In statistics, M-estimators are a broad class of estimators, which are obtained as the minima of sums of functions of the data. Least-squares estimators are M-estimators. The definition of M-estimators was motivated by robust statistics, which contributed new types of M-estimators. The statistical procedure of evaluating an M-estimator on a data set is called M-estimation.

More generally, an M-estimator may be defined to be a zero of an estimating function.[1][2][3][4][5][6] This estimating function is often the derivative of another statistical function: For example, a maximum-likelihood estimate is often defined to be a zero of the derivative of the likelihood function with respect to the parameter: thus, a maximum-likelihood estimator is often a critical point of the score function.[7] In many applications, such M-estimators can be thought of as estimating characteristics of the population.

Historical motivation

The method of least squares is a prototypical M-estimator, since the estimator is defined as a minimum of the sum of squares of the residuals.

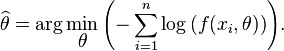

Another popular M-estimator is maximum-likelihood estimation. For a family of probability density functions f parameterized by θ, a maximum likelihood estimator of θ is computed for each set of data by maximizing the likelihood function over the parameter space { θ } . When the observations are independent and identically distributed, a ML-estimate  satisfies

satisfies

or, equivalently,

Maximum-likelihood estimators are often inefficient and biased for finite samples. For many regular problems, maximum-likelihood estimation performs well for "large samples", being an approximation of a posterior mode. If the problem is "regular", then any bias of the MLE (or posterior mode) decreases to zero when the sample-size increases to infinity. The performance of maximum-likelihood (and posterior-mode) estimators drops when the parametric family is mis-specified.

Definition

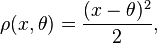

In 1964, Peter J. Huber proposed generalizing maximum likelihood estimation to the minimization of

where ρ is a function with certain properties (see below). The solutions

are called M-estimators ("M" for "maximum likelihood-type" (Huber, 1981, page 43)); other types of robust estimator include L-estimators, R-estimators and S-estimators. Maximum likelihood estimators (MLE) are thus a special case of M-estimators. With suitable rescaling, M-estimators are special cases of extremum estimators (in which more general functions of the observations can be used).

The function ρ, or its derivative, ψ, can be chosen in such a way to provide the estimator desirable properties (in terms of bias and efficiency) when the data are truly from the assumed distribution, and 'not bad' behaviour when the data are generated from a model that is, in some sense, close to the assumed distribution.

Types of M-estimators

M-estimators are solutions, θ, which minimize

This minimization can always be done directly. Often it is simpler to differentiate with respect to θ and solve for the root of the derivative. When this differentiation is possible, the M-estimator is said to be of ψ-type. Otherwise, the M-estimator is said to be of ρ-type.

In most practical cases, the M-estimators are of ψ-type.

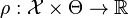

ρ-type

For positive integer r, let  and

and  be measure spaces.

be measure spaces.  is a vector of parameters. An M-estimator of ρ-type

is a vector of parameters. An M-estimator of ρ-type  is defined through a measurable function

is defined through a measurable function  . It maps a probability distribution

. It maps a probability distribution  on

on  to the value

to the value  (if it exists) that minimizes

(if it exists) that minimizes

:

:

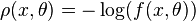

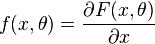

For example, for the maximum likelihood estimator,  , where

, where  .

.

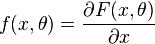

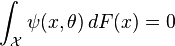

ψ-type

If  is differentiable, the computation of

is differentiable, the computation of  is usually much easier. An M-estimator of ψ-type T is defined through a measurable function

is usually much easier. An M-estimator of ψ-type T is defined through a measurable function  . It maps a probability distribution F on

. It maps a probability distribution F on  to the value

to the value  (if it exists) that solves the vector equation:

(if it exists) that solves the vector equation:

For example, for the maximum likelihood estimator,  , where

, where  denotes the transpose of vector u and

denotes the transpose of vector u and  .

.

Such an estimator is not necessarily an M-estimator of ρ-type, but if ρ has a continuous first derivative with respect to  , then a necessary corresponding M-estimator of ψ-type to be an M-estimator of ρ-type is

, then a necessary corresponding M-estimator of ψ-type to be an M-estimator of ρ-type is  . The previous definitions can easily be extended to finite samples.

. The previous definitions can easily be extended to finite samples.

If the function ψ decreases to zero as  , the estimator is called redescending. Such estimators have some additional desirable properties, such as complete rejection of gross outliers.

, the estimator is called redescending. Such estimators have some additional desirable properties, such as complete rejection of gross outliers.

Computation

For many choices of ρ or ψ, no closed form solution exists and an iterative approach to computation is required. It is possible to use standard function optimization algorithms, such as Newton-Raphson. However, in most cases an iteratively re-weighted least squares fitting algorithm can be performed; this is typically the preferred method.

For some choices of ψ, specifically, redescending functions, the solution may not be unique. The issue is particularly relevant in multivariate and regression problems. Thus, some care is needed to ensure that good starting points are chosen. Robust starting points, such as the median as an estimate of location and the median absolute deviation as a univariate estimate of scale, are common.

Properties

Distribution

It can be shown that M-estimators are asymptotically normally distributed. As such, Wald-type approaches to constructing confidence intervals and hypothesis tests can be used. However, since the theory is asymptotic, it will frequently be sensible to check the distribution, perhaps by examining the permutation or bootstrap distribution.

Influence function

The influence function of an M-estimator of  -type is proportional to its defining

-type is proportional to its defining  function.

function.

Let T be an M-estimator of ψ-type, and G be a probability distribution for which  is defined. Its influence function IF is

is defined. Its influence function IF is

assuming the density function  exists. A proof of this property of M-estimators can be found in Huber (1981, Section 3.2).

exists. A proof of this property of M-estimators can be found in Huber (1981, Section 3.2).

Applications

M-estimators can be constructed for location parameters and scale parameters in univariate and multivariate settings, as well as being used in robust regression.

Examples

Mean

Let (X1, ..., Xn) be a set of independent, identically distributed random variables, with distribution F.

If we define

we note that this is minimized when θ is the mean of the Xs. Thus the mean is an M-estimator of ρ-type, with this ρ function.

As this ρ function is continuously differentiable in θ, the mean is thus also an M-estimator of ψ-type for ψ(x, θ) = θ − x.

See also

References

- ↑ V. P. Godambe, editor. Estimating functions, volume 7 of Oxford Statistical Science Series. The Clarendon Press Oxford University Press, New York, 1991.

- ↑ Christopher C. Heyde. Quasi-likelihood and its application: A general approach to optimal parameter estimation. Springer Series in Statistics. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1997.

- ↑ D. L. McLeish and Christopher G. Small. The theory and applications of statistical inference functions, volume 44 of Lecture Notes in Statistics. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1988.

- ↑ Parimal Mukhopadhyay. An Introduction to Estimating Functions. Alpha Science International, Ltd, 2004.

- ↑ Christopher G. Small and Jinfang Wang. Numerical methods for nonlinear estimating equations, volume 29 of Oxford Statistical Science Series. The Clarendon Press Oxford University Press, New York, 2003.

- ↑ Sara A. van de Geer. Empirical Processes in M-estimation: Applications of empirical process theory, volume 6 of Cambridge Series in Statistical and Probabilistic Mathematics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000.

- ↑ Ferguson, Thomas S. (1982). "An inconsistent maximum likelihood estimate". Journal of the American Statistical Association 77 (380): 831–834. doi:10.1080/01621459.1982.10477894. JSTOR 2287314.

Further reading

- Andersen, Robert (2008). Modern Methods for Robust Regression. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences 152. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-4072-6.

- Godambe, V. P. (1991). Estimating functions. Oxford Statistical Science Series 7. New York: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852228-7.

- Heyde, Christopher C. (1997). Quasi-likelihood and its application: A general approach to optimal parameter estimation. Springer Series in Statistics. New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/b98823. ISBN 978-0-387-98225-0.

- Huber, Peter J. (2009). Robust Statistics (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-12990-6.

- Hoaglin, David C.; Frederick Mosteller; John W. Tukey (1983). Understanding Robust and Exploratory Data Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 0-471-09777-2.

- McLeish, D.L.; Christopher G. Small (1989). The theory and applications of statistical inference functions. Lecture Notes in Statistics 44. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-96720-2.

- Mukhopadhyay, Parimal (2004). An Introduction to Estimating Functions. Harrow, UK: Alpha Science International, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84265-163-6.

- Press, WH; Teukolsky, SA; Vetterling, WT; Flannery, BP (2007), "Section 15.7. Robust Estimation", Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8

- Serfling, Robert J. (2002). Approximation theorems of mathematical statistics. Wiley Series in Probability and Mathematical Statistics. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-21927-9.

- Shapiro, Alexander (2000). "On the asymptotics of constrained local M-estimators". Annals of Statistics 28 (3): 948–960. doi:10.1214/aos/1015952006. JSTOR 2674061. MR 1792795.

- Small, Christopher G.; Jinfang Wang (2003). Numerical methods for nonlinear estimating equations. Oxford Statistical Science Series 29. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850688-1.

- van de Geer, Sara A. (2000). Empirical Processes in M-estimation: Applications of empirical process theory. Cambridge Series in Statistical and Probabilistic Mathematics 6. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.2277/052165002X. ISBN 978-0-521-65002-1.

- Wilcox, R. R. (2003). Applying contemporary statistical techniques. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. pp. 55–79.

- Wilcox, R. R. (2012). Introduction to Robust Estimation and Hypothesis Testing, 3rd Ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

External links

- M-estimators — an introduction to the subject by Zhengyou Zhang

![\operatorname{IF}(x;T,G) = -\frac{\psi(x,T(G))}

{\int\left[\frac{\partial\psi(y,\theta)}

{\partial\theta}

\right] f(y) \mathrm{d}y

}](../I/m/d85bbe9999b9123a6c7671fe4fa2329c.png)