Lucille Teasdale-Corti

| Lucille Teasdale-Corti | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

January 30, 1929 Montreal East, Canada |

| Died |

August 1, 1996 (aged 67) Besana in Brianza, Italy |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Other names | Lucille Teasdale |

| Occupation | Medical doctor and surgeon |

| Known for | Surgeon and international aid worker |

| Awards |

Order of Canada National Order of Quebec |

Lucille Teasdale-Corti, CM GOQ (January 30, 1929 – August 1, 1996) was a Canadian physician, surgeon and international aid worker, who worked in Uganda and contributed to the development of medical services in the country.

Early life in Canada

Born in Montreal East, Quebec on 30 January 1929, Lucille Teasdale was the fourth of seven children. Her father René ran a grocery store in Avenue Guybourg, Saint-Léonard, Montreal.[1]

She was educated as a boarder at Collège Jésus-Marie d'Outrement, a select Catholic college[2] by nuns whose methods she thought to be very strict. A visit to the college by some nuns who had worked as missionaries in China acted as a catalyst for her, then aged 12,[3] to consider becoming a doctor,[4] this coming on top of voluntary work which she had done in a clinic serving the disadvantaged people of the Plateau Mont-Royal from which she had gained a conviction that the worst injustice was disease and that she could do something about it.[2]

She won a scholarship to attend medical school at the University of Montreal, starting in 1950. Females were not common in the medical profession at that time and her class of 110 students included only eight women. She graduated in 1955, becoming one of the first female surgeons in Quebec, and took work at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine, Montreal.[3]

It was at this time, while working in the pediatric department,[5] that she first met the Italian doctor, Piero Corti. He was working at the hospital to obtain a specialist qualification in pediatrics, to add to those in radiology and neuropsychiatry which he already had. Corti showed an interest in her but Teasdale was concentrating on her job, working up to 16 hours a day and sometimes fainting in the operating theater as a consequence.[6]

A condition of completing her postgraduate training was that she must agree to work for a period of time in a hospital abroad. Teasdale tried to obtain work in the USA but was turned down by 20 hospitals. She later said that this was "probably because I was a woman".[3][7]

France and Uganda

In September 1960 Lucille traveled to France to work at l'Hôpital de la Conception in Marseille, and, although she lacked confidence in her own abilities she was nonetheless highly regarded by staff members there.[8] She had been unhappy with the Canadian health-care system which, to her, appeared to be an immoral one because it had both private and public sectors, and patients in the private sector obtained better treatment. She thought indeed that medicine was so interesting that doctors should pay for the honor of practicing it.[9]

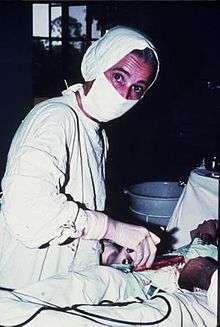

It was while working in Marseilles that Corti approached her: he needed a surgeon at a small clinic which had been established in Uganda and to which he had recently been invited and had hopes of turning into a hospital. The clinic was located in a small village of the Acoli tribe, 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) from Gulu (2°46′34″N 32°15′07″E / 2.776154°N 32.252026°E) It was run by a staff of six Combonian nuns and consisted of an outpatient unit and around 40 maternity beds.[10] She agreed to go with Corti, initially for a period of two months, and arrived in May 1961.[3] On 10 June 1961 she performed her first operation,[11] on a makeshift table, and thereafter spent mornings treating outpatients and afternoons in theater.[3]

Facilities improved as Corti spent his time soliciting donations from abroad. The clinic was renamed Lacor Hospital, after the nearby town, and Teasdale returned to France after extending her stay from two months to four.[3]

She returned in December 1961, finding herself unable to be separated from Corti. They were married in the hospital chapel on 5 December and on 17 November 1962 she gave birth to their daughter Dominique.[12] At this time Teasdale was seeing around 300 outpatients each morning and then performing operations in the afternoon, in conditions which were poor due to, amongst other things, a fluctuating supply of electricity, shortage of suitable medication and the poor quality of the water supplied.[3]

She also spent time educating Acoli mothers who were uninformed about medical science and were utilising the traditional practice of ebino, the extraction of infants' canine tooth buds, which supposedly cures disease, but in fact often causes bacterial infections.[13][14]

Uganda, a British protectorate, gained independence on 9 October 1962. Years of civil unrest and then outright civil war followed, involving the supporters of the dictators Amin Dada (1971–1978), Milton Obote (1979–1985) and the Lord’s Resistance Army (1986–2006), as well as an invasion by Tanzanian troops.[10] By the end of Amin's period in power there had been an estimated 300,000 victims.[3] The hospital received its share of the wounded and the dying, causing Teasdale-Corti to become a war surgeon and increasing her workload further.[15] The hospital not merely dealt with the casualties but also suffered from looting and the kidnap of staff members.[3] During this time Teasdale continued to expand her abilities and expertise and, in 1979, performed her first bone graft, this being on a wounded soldier in an attempt to avoid the alternative of amputation,.[16]

In 1972 she and her husband established a school of nursing at the hospital to train local people; from 1982 she ran a program at Makerere University, Kampala for the training of surgical residents and also arranged the work preparation of Italian doctors intending to work in Africa.[17]

She was a mentor, champion and a great friend to Matthew Lukwiya, another distinguished doctor at the same hospital, who later died of ebola there.[18]

Illness

Teasdale-Corti had prided herself on her stamina, working extremely long hours in difficult circumstances.[3] When her health began to deteriorate and her ability to sustain a heavy workload was consequently reduced, she sought medical advice for herself. The diagnosis, which is variously said to have been made in Italy[3] and by Anthony Pinching (an immunologist) in London,[19] was that she was suffering from AIDS, probably as a consequence of operating on a victim of the civil war.

She suffered the consequences of the illness for a further eleven years,[3] with trips to San Raffaele Hospital in Milan in order to receive treatment for herself. She died on 1 August 1996, weighing 33 kg,[20] in Besana in Brianza, Italy, to which she had recently moved in search of treatment for herself.[21] A copy of what is believed to be her last letter exists and describes the situation of both the hospital and herself at the time.[22] Her body was returned to Uganda and interred in the grounds of the hospital.[5] A few months after her death Corti had his fourth heart attack;[10] and he eventually died seven years later, of pancreatic cancer. He had continued working at the hospital, had conducted research into AIDS with Dr J W Carswell,[23] and was buried next to his wife.[5]

In 1993, three years before her death she and her husband had established the Lucille Teasdale and Piero Corti Foundation in Montreal, followed two years later by a similar body based in Milan.[3][24] These were intended to ensure the continued existence of the hospital.[25][26] By that time she had performed more than 13,000 operations and the hospital had grown to have 465 beds and departments covering numerous specialities.[3] As at 2011 Dominique, the couple's daughter and herself a doctor of medicine, continues to run the Foundations.[3][24]

A TV movie of the story was made in 2000.[27]

Honours and recognition

- In 1986, she and her husband were awarded the World Health Organization's Sasakawa Health Prize, "given to one or more persons, institutions or non-governmental organizations having accomplished outstanding innovative work in health development, in order to encourage the further development of such work".[28]

- In 1991 she was made a Member of the Order of Canada.[17]

- In 1995 she was made a Grand Officer of the National Order of Quebec.[29]

- In 1996 she was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by the University of Montreal.[17]

- In 1999 Parc Lucille-Teasdale in Montreal was named in her honour. (45°17′45″N 73°21′21″W / 45.2959°N 73.3559°W)

- In 2000 Canada Post issued a 46 cent stamp in her honour.[30]

- In 2001 she was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame.[17][31]

- In 2001 Lucille-Teasdale secondary school in Blainville, Quebec was built and it has been named in her honour. (45°43′15″N 73°53′49″W / 45.72085°N 73.897018°W)

- In 2013 Lucille-Teasdale international school in Brossard, Quebec has been renamed in her honour. (45°26′55″N 73°28′39″W / 45.448563°N 73.477444°W)

- There is a CSSS (Centre de Santé et de Services Sociaux - Health and Social Service Center) named after her in Montreal[32] (45°34′09″N 73°34′37″W / 45.569159°N 73.577042°W) and also a road, Boulevard Lucille Teasdale. (45°43′32″N 73°30′40″W / 45.725485°N 73.511245°W)

- She also received awards from the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei and the International Medical Women's Association.[29]

- The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada give an award named after her and Piero Corti for Canadian physicians "who, while providing health care or emergency medical services, go beyond the accepted norms of routine practice, which may include exposure to personal risk. The recipient's action will exemplify altruism and integrity, courage and perseverance in the alleviation of human suffering.for Canadian physicians who go beyond the accepted norms of routine practice to exemplify altruism and integrity, courage and perseverance in the alleviation of human suffering".[33]

References

- ↑ Arseneault p. 48

- 1 2 "Lucille Teasdale in The Great Names of the French Canadian Community". Fondation ConceptArt. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Famous Canadian Physicians: Dr Lucille Teasdale". Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 2011-02-16.

- ↑ Arseneault p. 51

- 1 2 3 "Piero Corti and Lucille Teasdale". Lacor Hospital. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ Arseneault p. 18

- ↑ Arseneault p. 22

- ↑ Arseneault p. 59

- ↑ Arseneault p. 62

- 1 2 3 "Who are we". Fondation Teasdale-Corti pour l'hôpital Lacor. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ Arseneault p. 72

- ↑ Arseneault p. 131

- ↑ Arseneault p. 122

- ↑ Iriso, R.; Accorsi, S.; Akena, S.; Amone, J. (2000). Fabiani, M., Ferrarese, N., Lukwiya, M., Rosolen, T. and Declich, S.. ""Killer" canines: the morbidity and mortality of ebino in northern Uganda". Tropical Medicine & International Health 5: 706–710. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00625.x. PMID 11044265.

- ↑ Arseneault p. 179

- ↑ Arseneault p. 213

- 1 2 3 4 "Dr Lucille Teasdale-Corti". The Canadian Medical Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ Blaine Harden (February 18, 2001). "Dr. Matthew's Passion-". New York Times.

- ↑ Arseneault p. 226

- ↑ Arseneault p. 323

- ↑ Arseneault p. 327

- ↑ "Full transcript of the last letter from an ill and tired Lucille Teasdale, unofficial translation". Library & Archives Canada. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ Arseneault p. 229

- 1 2 "Who are we". Fondation Teasdale-Corti pour l'hôpital Lacor. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ "Fondazione onlus Piero e Lucille Corti per Lacor Hospital (in Italian/English)". Fondazione onlus Piero e Lucille Corti. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ "Fondation Teasdale-Corti pour l'hôpital Lacor (in French/English)". Fondation Teasdale-Corti pour l'hôpital Lacor. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑

- ↑ "The Sasakawa Health Prize". World Health Organization.

- 1 2 "AIDS claims medical pioneer, humanitarian". Canadian Medical Association Journal 155 (6): 741. 1996-09-15. PMC 1335237. PMID 8925492.

- ↑ Canadian Medical Association Journal (Canadian Medical Association) 162 (9). 2000-05-02 http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/162/9/1337-a. Retrieved 2011-02-17. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Seven new inductees named to Canadian Medical Hall of Fame". Canadian Medical Association Journal 164 (8). 2001-04-17. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ "CSSS Lucille Teasdale". Government of Quebec. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ "RCPSC Teasdale-Corti Humanitarian Award". RCPSC. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

Bibliography

- Arseneault, Michel (1999). Un sogno per la vita Lucille e Piero Corti, una coppia di medici in prima linea (in Italian). Torino: Paoline Editoriale Libri. ISBN 9788831517829.

- Cowley, Deborah (2005). Lucille Teasdale: Doctor of Courage. XYZ Publishing. ISBN 1-894852-16-8.

External links

- "Canada and the World: Lucille Teasdale". Historica Dominion. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- "St. Mary's Hospital Lacor". St. Mary's Hospital Lacor. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- Teasdale-Corti Foundation

- in French/English: "Fondation Teasdale-Corti pour l'hôpital Lacor". Fondation Teasdale-Corti pour l'hôpital Lacor. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- in Italian/English: "Fondazione onlus Piero e Lucille Corti per Lacor Hospital". Fondazione onlus Piero e Lucille Corti. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- "Société Radio-Canada 1995 interview" (in French). Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- "Teasdale-Corti Global Health Research Partnership Program". The International Development Research Centre (IDRC). Archived from the original on 2006-05-05. Retrieved 2011-02-17.