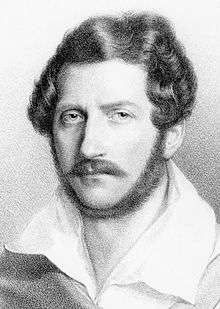

Lucia di Lammermoor

Lucia di Lammermoor is a dramma tragico (tragic opera) in three acts by Gaetano Donizetti. Salvadore Cammarano wrote the Italian language libretto loosely based upon Sir Walter Scott's historical novel The Bride of Lammermoor.[1]

Donizetti wrote Lucia di Lammermoor in 1835, a time when several factors led to the height of his reputation as a composer of opera. Gioachino Rossini had recently retired and Vincenzo Bellini had died shortly before the premiere of Lucia leaving Donizetti as "the sole reigning genius of Italian opera".[2] Not only were conditions ripe for Donizetti's success as a composer, but there was also a European interest in the history and culture of Scotland. The perceived romance of its violent wars and feuds, as well as its folklore and mythology, intrigued 19th century readers and audiences.[2] Sir Walter Scott made use of these stereotypes in his novel The Bride of Lammermoor, which inspired several musical works including Lucia.[3]

The story concerns the emotionally fragile Lucy Ashton (Lucia) who is caught in a feud between her own family and that of the Ravenswoods. The setting is the Lammermuir Hills of Scotland (Lammermoor) in the 17th century.

Performance history

19th century

The opera premiered on 26 September 1835 at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples. However, John Black notes that "the surprising feature of its subsequent performance history is that it established so slowly in the Neapolitan repertoire",[4] noting that while there were 18 performances in the rest of 1835, there were only four in 1836, 16 in 1837, two in 1838, and continuing in this manner with only two in each of 1847 and 1848.[4]

London saw the opera on 5 April 1838 and, for Paris, Donizetti revised the score for a French version which debuted on 6 August 1839 at the Théâtre de la Renaissance in Paris. It reached the United States with a production in New Orleans on 28 December 1841.[5]

20th century and beyond

The opera was never absent from the repertory of the Metropolitan Opera for more than one season at a time from the entire period from 1903 until 1972. After World War II, a number of sopranos including Maria Callas (with performances from 1952 at La Scala and Berlin in 1954/55 under Herbert von Karajan) and then Dame Joan Sutherland (with her 1959 and 1960 performances at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden), were instrumental in giving new life to the opera.

It has remained a staple of the standard operatic repertoire, and appears as number 21 on the Operabase list of the most-performed operas worldwide from the 2008/09 to 2012/13 season.[6]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 26 September 1835 (Conductor: – ) |

|---|---|---|

| Lucia | coloratura soprano | Fanny Tacchinardi Persiani |

| Lord Enrico Ashton, Lord of Lammermoor; Lucia's brother | baritone | Domenico Cosselli |

| Sir Edgardo di Ravenswood | tenor | Gilbert Duprez |

| Lord Arturo Bucklaw, Lucia's bridegroom | tenor | Balestrieri |

| Raimondo Bidebent, a Calvinist chaplain | bass | Carlo Ottolini Porto |

| Alisa, Lucia's handmaid | mezzo-soprano | Teresa Zappucci |

| Normanno, huntsman; a retainer of Enrico | tenor | Anafesto Rossi |

| Retainers and servants, wedding guests | ||

Instrumentation

The instrumentation[7] is:

- Woodwinds: piccolo, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (in B-flat, A & C) and 2 bassoons

- Brass: 4 horns (in E-flat, B-flat, D, C, A, G, D-flat, E & A-flat), 2 trumpets (in B-flat, A, D & E), 3 trombones

- Percussion: timpani, triangle, bass drum, cymbals and campana (tubular bells)

- Strings: harp, first violins, second violins, violas, violoncellos and double basses.

Additionally an off-stage wind band is used.

Synopsis

Act 1

Scene 1: The gardens of Lammermoor Castle

Normanno, captain of the castle guard, and other retainers are searching for an intruder. He tells Enrico that he believes that the man is Edgardo, and that he comes to the castle to meet Enrico's sister, Lucia. It is confirmed that Edgardo is indeed the intruder. Enrico reaffirms his hatred for the Ravenswood family and his determination to end the relationship.

Scene 2: By a fountain at the entrance to the park, beside the castle

Lucia waits for Edgardo. In her famous aria "Regnava nel silenzio", Lucia tells her maid Alisa that she has seen the ghost of a girl killed on the very same spot by a jealous Ravenswood ancestor. Alisa tells Lucia that the apparition is a warning and that she must give up her love for Edgardo. Edgardo enters; for political reasons, he must leave immediately for France. He hopes to make his peace with Enrico and marry Lucia. Lucia tells him this is impossible, and instead they take a sworn vow of marriage and exchange rings. Edgardo leaves.

Act 2

Scene 1: Lord Ashton's apartments in Lammermoor Castle

Preparations have been made for the imminent wedding of Lucia to Arturo. Enrico worries about whether Lucia will really submit to the wedding. He shows his sister a forged letter seemingly proving that Edgardo has forgotten her and taken a new lover. Enrico leaves Lucia to further persuasion this time by Raimondo, Lucia's chaplain and tutor, that she should renounce her vow to Edgardo, for the good of the family, and marry Arturo.

Scene 2: A hall in the castle

Arturo arrives for the marriage. Lucia acts strangely, but Enrico explains that this is due to the death of her mother. Arturo signs the marriage contract, followed reluctantly by Lucia. At that point Edgardo suddenly appears in the hall. Raimondo prevents a fight, but he shows Lucia's signature on the marriage contract to Edgardo. He curses her, demanding that they return their rings to each other. He tramples his ring on the ground, before being forced out of the castle.

Act 3

Scene 1: The Wolf's Crag

Enrico visits Edgardo to challenge him to a duel. He tells him that Lucia is already enjoying her bridal bed. Edgardo agrees to fight him. They will meet later by the graveyard of the Ravenswoods, near the Wolf's Crag.

Scene 2: A Hall in Lammermoor Castle

Raimondo interrupts the marriage celebrations to tell the guests that Lucia has gone mad and killed her bridegroom Arturo. Lucia enters. In the aria "Il dolce suono" she imagines being with Edgardo, soon to be happily married. Enrico enters and at first threatens Lucia but later softens when he realizes her condition. Lucia collapses. Raimondo blames Normanno for precipitating the whole tragedy.

Scene 3: The graveyard of the Ravenswood family

Edgardo is resolved to kill himself on Enrico's sword. He learns that Lucia is dying and then Raimondo comes to tell him that she has already died. Edgardo stabs himself with a dagger, hoping to be reunited with Lucia in heaven.[10]

Music

The "Mad Scene"

The "Mad Scene", "Il dolce suono... Spargi d'amaro pianto", has historically been a vehicle for several coloratura sopranos (providing a breakthrough for Dame Joan Sutherland) and is a technically and expressively demanding piece. Donizetti wrote it in F major, but it is often transposed down a tone (two half-steps) into E-flat.

Some sopranos, including Maria Callas, have performed the scene in a come scritto ("as written") fashion, adding minimal ornamentation to their interpretations. Most sopranos, however, add ornamentation to demonstrate their technical ability, as was the tradition in the bel canto period. This involves the addition and interpolation of trills, mordents, turns, runs and cadenzas. Almost all sopranos append cadenzas to the end of the "Mad Scene", sometimes ending them on a high keynote (E-flat or F, depending on the key in which they are singing though Mado Robin takes an even higher B-flat[11]). Some sopranos, including Ruth Welting[12] and Mariella Devia[13] have sung the "Mad Scene" in Donizetti's original F major key, although E-flat is more commonly heard.

The original scoring of this scene was for glass harmonica, but this was later replaced by the more usual arrangement with two flutes.

The popular soprano and flute duet cadenza was composed in 1888 by Mathilde Marchesi for her student Nellie Melba's performance of the role, requiring ten weeks of rehearsal for the new addition and causing a critical reevaluation and surge of new interest in the opera.[14]

List of arias and musical numbers

The index of Bonynge's edition lists the following numbers.

|

1. "Preludio" |

Act 2 |

Act 3 |

Lucie de Lammermoor (French version)

After the original had been performed in Paris, a French version of Lucia di Lammermoor was commissioned for the Théâtre de la Renaissance in Paris while Donizetti was living there preparing the revision of Poliuto into its French version which became Les Martyrs. Lucie opened on 6 August 1839 and subsequently this version was extensively toured throughout France. The libretto, written by Alphonse Royer and Gustave Vaëz, is not simply a translation, as Donizetti altered some of the scenes and characters. One of the more notable changes is the disappearance of Alisa, Lucia's friend. This allows the French version to isolate Lucia and to leave a stronger emotional impact than that left by the original. Furthermore, Lucia loses most of Raimondo's support; his role is dramatically diminished while Arturo gets a bigger part. Donizetti creates a new character, Gilbert, who is loosely based on the huntsman in the Italian version. However, Gilbert is a more developed figure and serves both Edgardo and Enrico, divulging their secrets to the other for money.

The French version is far less frequently performed than the Italian, but it was revived to great acclaim by Natalie Dessay and Roberto Alagna at the Opéra National de Lyon in 2002. It was also co-produced by the Boston Lyric Opera and the Glimmerglass Opera with Sarah Coburn singing the title role as her first "Lucia" in this French version in 2005. In 2008 Lucie was produced by the Cincinnati Opera with Sarah Coburn again in the title role.

Recordings

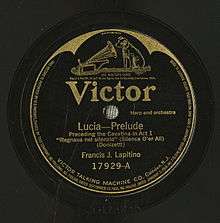

|

Prelude to Lucia di Lammermoor

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Both the Italian and French versions have received multiple recordings, although the Italian version predominates. One of the earliest versions was recorded in 1929 with Lorenzo Molajoli conducting the La Scala Orchestra and Chorus and Mercedes Capsir in the title role. There are several recordings with Maria Callas in the title role, including two versions conducted by Tullio Serafin (1953 and 1959) and one by Herbert von Karajan (1955). Joan Sutherland, who was particularly noted for performances as Lucia, has also recorded the opera several times including the 1971 Decca recording conducted by Richard Bonynge with Luciano Pavarotti as Edgardo. In 2002, Chandos Records released a recording in English of the Italian version conducted by David Parry with Elizabeth Futral As Lucia.[15]

Cultural references and adaptations

The "Lucia Sextet" ("Chi mi frena in tal momento?") was recorded in 1908 by Enrico Caruso, Marcella Sembrich, Antonio Scotti, Marcel Journet, Barbara Severina, and Francesco Daddi, (Victor single-sided 70036) and released at the price of $7.00, earning it the title of "The Seven-Dollar Sextet". The film The Great Caruso incorporates a performance of this sextet. The sextet's melody is used in Howard Hawks' gangster classic Scarface. Tony Camonte (Paul Muni) whistles "Chi mi frena?" ("What restrains me?") whenever he is about to kill someone, and the tune becomes a signifier for his murders.[16] The "Lucia Sextet" melody also figures in two scenes from the 2006 film The Departed, directed by Martin Scorsese. In one scene, Jack Nicholson's character is shown at a performance of Lucia di Lammermoor, and the music on the soundtrack is from the sextet. Later in the film, Nicholson's cell phone ringtone is the sextet melody.

The sextet has also been used in comedy and cartoon films. The American slapstick team, The Three Stooges used it in their short films Micro-Phonies and Squareheads of the Round Table, sung in the latter with the lyrics "Oh, Elaine, Elaine, come out ...", and it appears during a scene from the 1986 comedy film, The Money Pit. Its use in Warner Bros. cartoons includes Long-Haired Hare, sung by the opera singer (Bugs Bunny's antagonist); Book Revue, sung by the wolf antagonist; and in Back Alley Oproar, sung by a choir full of Sylvesters. In a season one episode of The Flintstones entitled "The Split Personality", Fred's alter ego Frederick (also voiced by Alan Reed) performs the sextet by himself quite poorly. In the 1946 Disney short, The Whale Who Wanted To Sing At The Met, the sextet appears in a unique interpretation with all parts performed by Nelson Eddy. In the film Because You're Mine, some soldiers sing a parody of the tune mockingly to Mario Lanza as he performs Army chores.

The "Mad Scene" aria "Il dolce suono" appears in the Luc Besson film The Fifth Element in a performance by the alien diva Plavalaguna (voiced by Albanian soprano Inva Mula and played onscreen by French actress Maïwenn Le Besco). Mula's performance is also used in an episode of Law & Order: Criminal Intent involving the murder of a young violinist by her opera singer mother (who performs the song right after the murder), and as a backdrop to "The Eye of Zion's Pocket" incorrectly credited to the Chemical Brothers for the Matrix Reloaded soundtrack (the original artist is unknown). The aria was covered by Russian pop singer Vitas over a heavily reworked orchestral techno score and released as a music video in 2006. In addition to the "Mad Scene", "Verranno a te sull'aure", and "Che facesti?" appear prominently in the 1983 Paul Cox film Man of Flowers, especially "Verranno a te sull'aure", which accompanies a striptease in the film's opening scene. "Regnava nel silenzio" accompanies the scene in Beetlejuice in which Lydia (Winona Ryder) composes a suicide note.

The opera is mentioned in the novels The Count of Monte Cristo, Madame Bovary, The Hotel New Hampshire, and Where Angels Fear to Tread and a performance of Lucia is a pivotal event in Tolstoy's Anna Karenina.[17] In the children's book The Cricket in Times Square, Chester Cricket chirps the tenor part to the "Lucia Sextet" as the encore to his farewell concert, literally stopping traffic in the process.

References

Notes

- ↑ The plot of Sir Walter Scott's original novel is based on an actual incident that took place in 1669 in the Lammermuir Hills area of Lowland Scotland. The real family involved were the Dalrymples. While the libretto retains much of Scott's basic intrigue, it also contains very substantial changes in terms of characters and events. In Scott's novel, it is her mother, Lady Ashton, not Enrico, who is the villain and evil perpetrator of the whole intrigue. Also, Bucklaw was only wounded by Lucy after their unfortunate wedding, and he later recovered, went abroad, and survived them all. In the opera, Lucia's descent into insanity is more speedy and dramatic and very spectacular, while, in the book, it is more mysterious and ambiguous. Also, in the novel, Edgar and Lucy's last talk and farewell (supervised by her mother) is far less melodramatic and more calm, though the final effect is equally devastating for both of them. At the end of the novel, Edgar disappears (his body never found) and is presumably killed in some sort of an accident on his way to have his duel with Lucy's older brother; therefore, he does not commit a spectacular, operatic style suicide with a stiletto on learning of Lucy's death.

- 1 2 Mackerras, p. 29

- ↑ Mackerras, p. 30

- 1 2 Black, pp. 34—35

- ↑ Ashbrook and Hibberd 2001, p. 236

- ↑ Performance statistics. Accessed 13 November 2013

- ↑ Free full score in IMSLP

- ↑ Enrico mentions the death of "William", assumedly William III who died in 1702

- ↑ Osborne, p. 240

- ↑ This synopsis by Simon Holledge was first published on Opera japonica (www.operajaponica.org) and appears here by permission.

- ↑ Mado Robin sings Bb over high C!!!. Youtube.com (television). Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ↑ Forbes, Elizabeth, Obituary: Ruth Welting, The Independent, 23 December 1999. Accessed 6 February 2009.

- ↑ Youtube clip singing the "Mad Scene" in the F major key

- ↑ Pugliese, p. 32

- ↑ Lucia di Lammermoor Discography on Operadis

- ↑ "Lucia in Popular Culture". seattleoperablog. Seattle Opera. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- ↑ Polhemus, Robert M. (1990). Erotic Faith: Being in Love from Jane Austen to D. H. Lawrence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-226-67322-7.

Cited sources

- Ashbrook, William; Sarah Hibberd (2001), in Holden, Amanda (Ed.), The New Penguin Opera Guide, New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 0-14-029312-4.

- Black, John (1982), Donizetti’s Operas in Naples, 1822—1848. London: The Donizetti Society.

- Mackerras, Sir Charles (1998). Lucia di Lammermoor (CD booklet). Sony Classical. pp. 29–33. ISBN 0-521-27663-2.

- Osborne, Charles (1994), The Bel Canto Operas of Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini, Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-71-3

- Pugliese, Romana (March 2004), Martin Deasy, "The Origins of Lucia di Lammermoor's Cadenza", Cambridge Opera Journal 16,1: 23–42

Other sources

- Allitt, John Stewart (1991), Donizetti: in the light of Romanticism and the teaching of Johann Simon Mayr, Shaftesbury: Element Books, Ltd (UK); Rockport, MA: Element, Inc. (USA)

- Ashbrook, William (1982), Donizetti and His Operas, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23526-X

- Ashbrook, William (1998), "Donizetti, Gaetano" in Stanley Sadie (Ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Vol. One. London: MacMillan Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-333-73432-7 ISBN 1-56159-228-5

- Boyden, Matthew (2007), The Rough Guide to Operas (4th ed.), Rough Guides, ISBN 1-84353-538-6

- Cipriani, Nicola (2008), Varese, ed., Le tre Lucie: un romanzo, un melodramma, un caso giudiziario : il percorso di tre vittime del pensiero maschile, Zecchini, p. 276, ISBN 88-87203-66-0

- Fisher, Burton D. (2005), Lucia di Lammermoor, Opera Journeys Publishing, ISBN 1-930841-79-5

- Loewenberg, Alfred (1970). Annals of Opera, 1597–1940, 2nd edition. Rowman and Littlefield

- Osborne, Charles, (1994), The Bel Canto Operas of Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini, Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-71-3

- Sadie, Stanley, (Ed.); John Tyrell (Exec. Ed.) (2004), The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 2nd edition. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-19-517067-2 (hardcover). ISBN 0-19-517067-9 OCLC 419285866 (eBook).

- Weinstock, Herbert (1963), Donizetti and the World of Opera in Italy, Paris, and Vienna in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, New York: Pantheon Books. LCCN 63-13703

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lucia di Lammermoor. |

- Lucia di Lammermoor: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Libretto of the French version at stanford.edu

- Italian libretto with line-by-line English, French, German libretto

- Libretto of the French version in the Magasin théâtral at the Internet Archive.

- Vocal score of the French version at the Internet Archive.

- Further Lucia di Lammermoor discography

- Lucia di Lammermoor synopsis (Metropolitan Opera)

- Online vocal score

- [http://operabase.com/oplist.cgi?from=01+01+2001&is=Lucia+di+Lammermoor&sort=D List of performances of Lucia di Lammermoor] on Operabase.

| ||||||

|