Lubbe v Cape plc

| Lubbe v Cape Plc | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | House of Lords |

| Decided | 20 July 2000 |

| Citation(s) | [2000] UKHL 41, [2000] 1 WLR 1545, [2000] 4 All ER 268 |

| Case history | |

| Prior action(s) | [2000] 1 Lloyd's Rep 139 |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Lord Bingham of Cornhill, Lord Steyn, Lord Hoffmann, Lord Hope of Craighead and Lord Hobhouse of Woodborough |

| Keywords | |

| Tort, corporate veil, duty of care, forum non conveniens, group of companies | |

Lubbe v Cape Plc [2000] UKHL 41 is a conflict of laws case, which is also highly significant for the question of lifting the corporate veil in relation to tort victims. In this case it was alleged, and postulated by the House of Lords, that in principle it is possible to show that a parent company owes a direct duty of care in tort to anybody injured by a subsidiary company in a group.

Facts

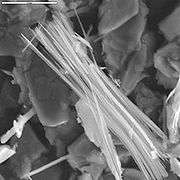

Mr Lubbe was injured at work while manufacturing asbestos for a South African subsidiary company of the UK parent company, Cape plc. The South African subsidiary had no money left and Cape Plc had no assets in South Africa. His case was one of 3000 claims. The case was initiated in the high court in London. He alleged that the parent, Cape Plc, owed a direct duty of care in tort to him as a worker in the company group. Cape Plc was applying to stay the actions on the basis of forum non conveniens, submitting that they were an abuse of process on grounds that intention to launch a multi party action was not disclosed to the court. Mr Lubbe argued that the claims should not be stayed since, in South Africa, the legal aid necessary to continue the claim had been withdrawn, no contingency fee arrangement was available and no other source of funding would be available. The Court of Appeal refused Mr Lubbe's arguments and continued the stay, and Mr Lubbe appealed to the House of Lords.

Judgment

The House of Lords held unanimously that although South Africa was the more appropriate forum for hearing the claim, it was highly likely that legal representation for the claimants would be unavailable. The expert evidence suggested a denial of justice would result, exacerbated by the lack of procedures in South Africa to accommodate multi-party actions. This meant that lifting the stay was appropriate and the action continued in the English courts.

Lord Bingham made the following remark about the tort issue,[1]

| “ | 20. The issues in the present cases fall into two segments. The first segment concerns the responsibility of the defendant as a parent company for ensuring the observance of proper standards of health and safety by its overseas subsidiaries. Resolution of this issue will be likely to involve an inquiry into what part the defendant played in controlling the operations of the group, what its directors and employees knew or ought to have known, what action was taken and not taken, whether the defendant owed a duty of care to employees of group companies overseas and whether, if so, that duty was broken. Much of the evidence material to this inquiry would, in the ordinary way, be documentary and much of it would be found in the offices of the parent company, including minutes of meetings, reports by directors and employees on visits overseas and correspondence.

21. The second segment of the cases involves the personal injury issues relevant to each individual: diagnosis, prognosis, causation (including the contribution made to a plaintiff's condition by any sources of contamination for which the defendant was not responsible) and special damage. Investigation of these issues would necessarily involve the evidence and medical examination of each plaintiff and an inquiry into the conditions in which that plaintiff worked or lived and the period for which he did so. Where the claim is made on behalf of a deceased person the inquiry would be essentially the same, although probably more difficult. |

” |

On a side issue, however, matters of public interest and policy were not relevant to determining which forum was best, and only private interests would be taken into account.[2]

Significance

The dicta of Lord Bingham were applied for the first time in Chandler v Cape plc.[3]

See also

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ [2000] 1 WLR 1545, 1556

- ↑ Spiliada Maritime Corp v Cansulex Ltd (The Spiliada) [1987] AC 460

- ↑ [2012] EWCA Civ 525, and see E McGaughey, 'Donoghue v Salomon in the High Court' (2011) 4 Journal of Personal Injury Law 249, on SSRN