Least common multiple

For example, a card game which requires its cards to be divided equally among up to 5 players requires at least 60 cards, the number at the intersection of the 2, 3, 4 and 5 sets, but not the 7 set.

In arithmetic and number theory, the least common multiple (also called the lowest common multiple or smallest common multiple) of two integers a and b, usually denoted by LCM(a, b), is the smallest positive integer that is divisible by both a and b.[1] Since division of integers by zero is undefined, this definition has meaning only if a and b are both different from zero.[2] However, some authors define lcm(a,0) as 0 for all a, which is the result of taking the lcm to be the least upper bound in the lattice of divisibility.

The LCM is familiar from grade-school arithmetic as the "lowest common denominator" (LCD) that must be determined before fractions can be added, subtracted or compared . The LCM of more than two integers is also well-defined: it is the smallest positive integer that is divisible by each of them.

Overview

A multiple of a number is the product of that number and an integer. For example, 10 is a multiple of 5 because 5 × 2 = 10, so 10 is divisible by 5 and 2. Because 10 is the smallest positive integer that is divisible by both 5 and 2, it is the least common multiple of 5 and 2. By the same principle, 10 is the least common multiple of −5 and 2 as well.

Notation

In this article we will denote the least common multiple of two integers a and b as lcm(a, b).

Some older textbooks use [a, b].[2][3]

The J (programming language) uses a*.b

Example

What is the LCM of 4 and 6?

Multiples of 4 are:

- 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, 28, 32, 36, 40, 44, 48, 52, 56, 60, 64, 68, 72, 76, ...

and the multiples of 6 are:

- 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 54, 60, 66, 72, ...

Common multiples of 4 and 6 are simply the numbers that are in both lists:

- 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, ....

So, from this list of the first few common multiples of the numbers 4 and 6, their least common multiple is 12.

Applications

When adding, subtracting, or comparing vulgar fractions, it is useful to find the least common multiple of the denominators, often called the lowest common denominator, because each of the fractions can be expressed as a fraction with this denominator. For instance,

where the denominator 42 was used because it is the least common multiple of 21 and 6.

Computing the least common multiple

Reduction by the greatest common divisor

The following formula reduces the problem of computing the least common multiple to the problem of computing the greatest common divisor (GCD), also known as the greatest common factor:

This formula is also valid when exactly one of a and b is 0, since gcd(a, 0) = |a|. (However, if both a and b are 0, this formula would cause division by zero; lcm(0, 0) = 0 is a special case.

There are fast algorithms for computing the GCD that do not require the numbers to be factored, such as the Euclidean algorithm. To return to the example above,

Because gcd(a, b) is a divisor of both a and b, it is more efficient to compute the LCM by dividing before multiplying:

This reduces the size of one input for both the division and the multiplication, and reduces the required storage needed for intermediate results (overflow in the a×b computation). Because gcd(a, b) is a divisor of both a and b, the division is guaranteed to yield an integer, so the intermediate result can be stored in an integer. Done this way, the previous example becomes:

Finding least common multiples by prime factorization

The unique factorization theorem says that every positive integer greater than 1 can be written in only one way as a product of prime numbers. The prime numbers can be considered as the atomic elements which, when combined together, make up a composite number.

For example:

Here we have the composite number 90 made up of one atom of the prime number 2, two atoms of the prime number 3 and one atom of the prime number 5.

This knowledge can be used to find the LCM of a set of numbers.

Example: Find the value of lcm(8,9,21).

First, factor out each number and express it as a product of prime number powers.

The lcm will be the product of multiplying the highest power of each prime number together. The highest power of the three prime numbers 2, 3, and 7 is 23, 32, and 71, respectively. Thus,

This method is not as efficient as reducing to the greatest common divisor, since there is no known general efficient algorithm for integer factorization, but is useful for illustrating concepts.

This method can be illustrated using a Venn diagram as follows. Find the prime factorization of each of the two numbers. Put the prime factors into a Venn diagram with one circle for each of the two numbers, and all factors they share in common in the intersection. To find the LCM, just multiply all of the prime numbers in the diagram.

Here is an example:

- 48 = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3,

- 180 = 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 5,

and what they share in common is two "2"s and a "3":

- Least common multiple = 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 × 3 × 3 × 5 = 720

- Greatest common divisor = 2 × 2 × 3 = 12

This also works for the greatest common divisor (GCD), except that instead of multiplying all of the numbers in the Venn diagram, one multiplies only the prime factors that are in the intersection. Thus the GCD of 48 and 180 is 2 × 2 × 3 = 12.

A simple algorithm

This method works as easily for finding the LCM of several integers.

Let there be a finite sequence of positive integers X = (x1, x2, ..., xn), n > 1. The algorithm proceeds in steps as follows: on each step m it examines and updates the sequence X(m) = (x1(m), x2(m), ..., xn(m)), X(1) = X, where X(m) is the mth iteration of X, i.e. X at step m of the algorithm, etc. The purpose of the examination is to pick the least (perhaps, one of many) element of the sequence X(m). Assuming xk0(m) is the selected element, the sequence X(m+1) is defined as

- xk(m+1) = xk(m), k ≠ k0

- xk0(m+1) = xk0(m) + xk0(1).

In other words, the least element is increased by the corresponding x whereas the rest of the elements pass from X(m) to X(m+1) unchanged.

The algorithm stops when all elements in sequence X(m) are equal. Their common value L is exactly LCM(X).

A method using a table

This method works for any number of factors. One begins by listing all of the numbers vertically in a table (in this example 4, 7, 12, 21, and 42):

- 4

- 7

- 12

- 21

- 42

The process begins by dividing all of the factors by 2. If any of them divides evenly, write 2 at the top of the table and the result of division by 2 of each factor in the space to the right of each factor and below the 2. If a number does not divide evenly, just rewrite the number again. If 2 does not divide evenly into any of the numbers, try 3.

| x | 2 |

|---|---|

| 4 | 2 |

| 7 | 7 |

| 12 | 6 |

| 21 | 21 |

| 42 | 21 |

Now, check if 2 divides again:

| x | 2 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 12 | 6 | 3 |

| 21 | 21 | 21 |

| 42 | 21 | 21 |

Once 2 no longer divides, divide by 3. If 3 no longer divides, try 5 and 7. Keep going until all of the numbers have been reduced to 1.

| x | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 |

| 12 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 21 | 21 | 21 | 7 | 1 |

| 42 | 21 | 21 | 7 | 1 |

Now, multiply the numbers on the top and you have the LCM. In this case, it is 2 × 2 × 3 × 7 = 84. You will get to the LCM the quickest if you use prime numbers and start from the lowest prime, 2.

Formulas

Fundamental theorem of arithmetic

According to the fundamental theorem of arithmetic a positive integer is the product of prime numbers, and, except for their order, this representation is unique:

where the exponents n2, n3, ... are non-negative integers; for example, 84 = 22 31 50 71 110 130 ...

Given two positive integers  and

and  their least common multiple and greatest common divisor are given by the formulas

their least common multiple and greatest common divisor are given by the formulas

and

Since

this gives

In fact, any rational number can be written uniquely as the product of primes if negative exponents are allowed. When this is done, the above formulas remain valid. For example:

Lattice-theoretic

The positive integers may be partially ordered by divisibility: if a divides b (i.e. if b is an integer multiple of a) write a ≤ b (or equivalently, b ≥ a). (Forget the usual magnitude-based definition of ≤ in this section - it isn't used.)

Under this ordering, the positive integers become a lattice with meet given by the gcd and join given by the lcm. The proof is straightforward, if a bit tedious; it amounts to checking that lcm and gcd satisfy the axioms for meet and join. Putting the lcm and gcd into this more general context establishes a duality between them:

- If a formula involving integer variables, gcd, lcm, ≤ and ≥ is true, then the formula obtained by switching gcd with lcm and switching ≥ with ≤ is also true. (Remember ≤ is defined as divides).

The following pairs of dual formulas are special cases of general lattice-theoretic identities.

It can also be shown[4] that this lattice is distributive, i.e. that lcm distributes over gcd and, dually, that gcd distributes over lcm:

This identity is self-dual:

Other

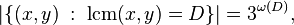

Let D be the product of ω(D) distinct prime numbers (i.e. D is squarefree).

Then[5]

where the absolute bars || denote the cardinality of a set.

The LCM in commutative rings

The least common multiple can be defined generally over commutative rings as follows: Let a and b be elements of a commutative ring R. A common multiple of a and b is an element m of R such that both a and b divide m (i.e. there exist elements x and y of R such that ax = m and by = m). A least common multiple of a and b is a common multiple that is minimal in the sense that for any other common multiple n of a and b, m divides n.

In general, two elements in a commutative ring can have no least common multiple or more than one. However, any two least common multiples of the same pair of elements are associates. In a unique factorization domain, any two elements have a least common multiple. In a principal ideal domain, the least common multiple of a and b can be characterised as a generator of the intersection of the ideals generated by a and b (the intersection of a collection of ideals is always an ideal).

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hardy & Wright, § 5.1, p. 48

- 1 2 Long (1972, p. 39)

- ↑ Pettofrezzo & Byrkit (1970, p. 56)

- ↑ The next three formulas are from Landau, Ex. III.3, p. 254

- ↑ Crandall & Pomerance, ex. 2.4, p. 101.

References

- Crandall, Richard; Pomerance, Carl (2001), Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective, New York: Springer, ISBN 0-387-94777-9

- Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (1979), An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (Fifth edition), Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-853171-5

- Landau, Edmund (1966), Elementary Number Theory, New York: Chelsea

- Long, Calvin T. (1972), Elementary Introduction to Number Theory (2nd ed.), Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company, LCCN 77-171950

- Pettofrezzo, Anthony J.; Byrkit, Donald R. (1970), Elements of Number Theory, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, LCCN 77-81766

.

.