Louis Laybourne Smith

| Louis Edouard Laybourne Smith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1 April 1880 Unley, South Australia |

| Died |

13 September 1965 (aged 85) Adelaide, South Australia |

| Occupation | Architect, teacher & registrar |

Louis Laybourne Smith CMG (1 April 1880 – 13 September 1965) was an architect and educator in South Australia. Born in the Adelaide inner-southern suburb of Unley, he became interested in engineering and architecture while in the goldfields of Western Australia and later studied mechanical engineering at the School of Mines, serving an apprenticeship under architect Edward Davies. After graduating he accepted a position as a lecturer at the school, and was responsible for developing the first formal architecture course in the State in 1904. Between 1905 and 1914, he served as registrar at the school before leaving to join his long-time friend, Walter Bagot, at the architectural firm of Woods, Bagot and Jory. He remained with the firm until his death in 1965, and over the years was involved in a number of significant projects, including the South Australian National War Memorial and the original Australian Mutual Provident building on King William Street.

Along with his teaching and professional duties, Laybourne Smith was a member of the South Australian Institute of Architects, the Federal Council of the Australian Institute of Architects, and the Australian Institute of Architects, as well as being on numerous committees and advising the State Government in the formation of both the State Building Act of 1923 and the 1939 Architects Act.

During his life Laybourne Smith received a number of awards and honours, including Life Fellowship to the Royal Australian Institute of Architects and the Royal Institute of British Architects, the Royal Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medal, and was named a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George. Today, the architectural school which he founded (now part of the University of South Australia) bears his name—the Louis Laybourne Smith School of Architecture.[1]

Early life and education

Louis Laybourne Smith was born to Joseph and Annie Laybourne Smith on 1 April 1880, in Unley, South Australia.[2] His parents had emigrated to Australia so that his father could take up a post as a chemist with F.H. Faulding & Co. However, it appears that Joseph Laybourne Smith found dentistry more to his liking, for he went on to gain qualifications in the field through the Australian College of Dentistry.[3] Both Laybourne Smith's primary and secondary education were obtained at the nearby Windham and Way colleges; his education was interrupted in the mid-1890s when his parents decided to move to the goldfields of Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie in Western Australia.[4]

According to Laybourne Smith, he became interested in machinery while in the goldfields. His parents decided to direct him towards architecture, as it "was the nearest thing to white-collar engineering work that they could think of".[5] He was articled to A. A. E. Dancker for a period[4] before returning to Adelaide in 1898.[2] Laybourne Smith's parents had intended for him to study architecture at the University of Adelaide, but there were no courses available at the time.[6] As a result, Laybourne Smith undertook to complete a mechanical engineering course part-time at the School of Mines, and (in order to pursue his interest in architecture) he was articled to Edward Davies from 1901.[2][7]

He proved to be an excellent student, winning scholarships in both his second and third years, and was the first person to finish the course within the proscribed four years.[8] He completed his apprenticeship with Davies in 1904, and was admitted as an Associate to the South Australian Institute of Architects,[8] although the ongoing impact of the depression made finding work difficult. In spite of this, he found employment as a draftsman, initially with Ernest Bayer and later with John Quinton Bruce.[9]

After graduating at the School of Mines, Laybourne Smith continued his studies at the University of Adelaide, completing a Bachelor of Science in 1911. This was surrendered in 1914 for a Bachelor of Engineering.[10]

Teaching career

In 1903, Laybourne Smith was invited to lecture in mechanical engineering at the School of Mines—a position which Page states that Laybourne Smith was "delighted" to accept. He was thereafter elected as the school's registrar in 1905,[9] and continued in that post full-time until 1914, after which he ran the school part-time until 1951.[2] Even then, Laybourne Smith's involvement with the school did not end after Gavin Walkley took over, and he was still associated with the school when he died in 1965.[4]

While working at the school, Laybourne Smith initiated his own classes on architecture, gathering "a group of colleagues who instructed one another" in the field.[11] After being approached in 1906 by the Council of the School of Mines, Laybourne Smith teamed with Walter Bagot to develop a new architecture course.[9] The result was a three-year part-time Associate Diploma, although students were still expected to be articled to professional architects in order to gain more practical experience in the field.[11] By 1916 the course was regarded as of sufficient quality to place its students "in the same rank as architectural students in other parts of the world".[12]

While the School of Mines no longer exists, the school of architecture founded by Laybourne Smith is now part of the University of South Australia, and since 1963 the Louis Laybourne Smith School of Architecture and Building has borne his name as its founder.[8]

Architectural career

Upon leaving his full-time position at the School of Mines, Laybourne Smith acted as a "stand-in" for Walter Bagot at Bagot's architectural firm, Woods, Bagot and Jory, while Bagot was overseas. Edward Woods died in 1913, and three years later Laybourne Smith became a full partner in the newly named Woods, Bagot, Jory & Laybourne Smith.[14] Laybourne Smith was to remain with the firm until his death in 1965.[15]

Laybourne Smith's friendship with Walter Bagot had spanned many years prior to the partnership, but their respective working methods was "so different that they seemed unlikely partners".[16] While Baggot was "notorious" for the attention he gave to minor details in designs, Laybourne Smith was described as being just as happy to develop a sketch and to pass it on to the draftsmen to "work up" (although it should be noted that this does not represent a lack of attention, as his designs were "sketched in tiny, neat detail").[2][16] In spite of these differences, their respective strengths tended to balance one another: Bagot was a traditionalist in design, while Laybourne Smith brought an engineer's knowledge and "ingenuity" to the partnership.[16]

Works

Laybourne Smith's first major work with Woods, Bagot & Jory was the refurbishment of the National Bank building on King William Street,[17] and from there he graduated to work on a number of notable buildings within South Australia and interstate. Both the firm in general and Laybourne Smith in particular were traditionalists in their designs, to the point where Page reports that Laybourne Smith took as a compliment a description of one of his works in 1965 as "striped pants and all".[18] This traditionalism was particularly evident in their work for the University of Adelaide. Between 1910 and 1945, the firm served as architects to the University of Adelaide,[18] and Bagot strove towards congruity for the university.[19] The result included a number of buildings that were designed by Laybourne Smith in a "Georgian revival" style, including the original heritage listed Student Union building and the main building of the Waite Agricultural Research Institute, which is also heritage listed and has been described as being "reministent of the great English country houses".[16][20] Similarly, Laybourne Smith applied traditional designs to a number of ecclesiastical projects. These include St Cuthbert's Anglican Church in North Adelaide, which is heritage listed as an example of Gothic Revival architecture;[21] and the romanesque St. Dominic's Chapel at the Cabra Dominican College in Cumberland Park.[22]

His background in engineering was put to good use on a number of projects. In particular, the John Martins store on Rundle Street (now Rundle Mall), was constructed by raising the top floor of the building on hydraulic jacks, building two new floors underneath while the remainder of the store continued to operate normally.[16] Another of Laybourne Smith's buildings, the Australian Mutual Provident building on King William Street in Adelaide, was one of the first in the state to feature air conditioning, as this was considered to be quite an "innovative" addition in 1934.[23]

Other works by Laybourne Smith include the facade on the Balfours Cafe in Rundle Mall (heritage listed in part due to the innovative "building envelope", which is "independent of the internal structure"),[24] the Repatriation General Hospital in Daw Park (developed by Laybourne Smith from sketch plans produced by Melbourne firm Stephenson & Turner), and the South Australian National War Memorial. This last structure represents a collaboration between Laybourne Smith, Walter Bagot, and Sydney-based sculptor Rayner Hoff. Although Walter Bagot produced the original design for the architectural competition in 1924, his design was, (along with the other entrants), deemed to be "unsuitable".[25] After the entries were destroyed by fire late that year, Laybourne Smith, working with artist Rayner Hoff, was able to redraw the design largely from memory in order to enter the subsequent 1926 competition.[26] In doing so they built upon Bagot's work, making the memorial "grander" in its scope—and this proved to be sufficient for the firm to be awarded the commission.[27]

-

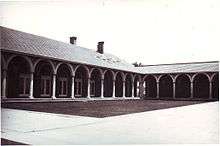

The Cloisters and Union Building at the University of Adelaide (1927) as it appeared in 1930.[1]

-

The South Australian National War Memorial (1931).

-

Australian Mutual Provident building, King William Street, Adelaide (1934).

-

.jpg)

The main building of the Repatriation Hospital, Daw Park, Adelaide (1941-1942).

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Ward2004was invoked but never defined (see the help page).

Professional activities and associations

Although Laybourne Smith continued to be involved in teaching and architectural design, he was also involved in professional organisations and committees. He was admitted to the South Australian Institute of Architects (SAIA) as an associate in 1904, made a fellow in 1907, elected to the council in 1909, and served two terms as President (1921–1923 and 1935–1937).[8] In all, Laybourne Smith served on the SAIA council for 50 years, from 1909 to 1959.[2]

Laybourne Smith played a significant role in the formation of a national body of architects. He was a founding member of the Federal Council of the Australian Institute of Architects, first proposed in 1914 and officially formed in 1915, which served as a "first step" towards the formation of a national body.[28][29] Between 1991 and 1922, he served as president of this body.[4] After the Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA) was formed (now known as the Australian Institute of Architects), he served as a councilor for 11 years (between 1933 and 1944), and as the President of the institute from 1937 to 1938.[4]

In addition to his role on the councils, Laybourne Smith was an adviser during the development of the State Building Act of 1923,[30] and he was largely responsible for the framing of the 1939 Architects Act, (which provided for the formal registration of architects in South Australia).[2] Because of his work on the State Building act, Laybourne Smith sat on the Board of Referees responsible for adjudicating disputes,[30] and his position on the Architects Board of South Australia was a direct result of his involvement in the creation of the Architects Act.[4]

Influence and awards

Louis Laybourne Smith is regarded as being one of the "key practitioners" of architecture in South Australia.[23] In particular, he had a significant influence on the direction of architectural education in South Australia.[4] His career spanned more than half a century, with much of it directly involved in education, and during that time he (and Walter Bagot) served as one of the "last links with the distant past of South Australian architecture"—having known (either directly or indirectly) most of the architects of the colonial era, while being responsible for the training of many of those who were to follow.[31]

Furthermore, he had a substantial impact on the development of architecture as a professional body through his involvement in the Architects Act of 1931 and the formation of a national body for architects.[4][30] This political work also had a social dimension: his work on the Building Act Advisory Committee helped to highlight the low quality of the housing in the poorer areas of Adelaide, and this led to a change in how the public viewed what was acceptable as low-income housing. The South Australian Housing Trust was a direct result of his actions, and led to the provision of low cost rental housing to working families in the state.[29]

As well as having the architectural school named in his honour, in 1961 Laybourne Smith was awarded the Gold Medal by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects,[2] and prior to that date, in 1948, he was appointed as a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George.[4] Two busts of his likeness have also been commissioned. One was by Rayner Hoff, with whom he had collaborated on the design for the South Australian National War Memorial, and is kept in the offices of Woods Bagot. The second was unveiled in 1961, and was sculpted by South Australian artist John Dowie.[2] It can be found at the Louis Laybourne Smith School of Architecture at the University of South Australia.[32]

Laybourne Smith was a Life Fellow with both the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, (awarded in 1944), and a Fellow (1939) and Life Fellow (1944) of the Royal Institute of British Architects.[4]

Personal life

Described as a "dapper young man with a moustache waxed into long points",[3] he made for a "dynamic figure with a penetrating voice",[2] and was noted for riding his Douglas motorcycle through the 1920s and 30s in his khaki overalls as he traveled between his professional practice, teaching duties and home life.[2][33] On the home front, Louis Laybourne Smith married Frances Maude Davies, the daughter of Edward Davies to whom he had been articled, on 9 April 1903. They had three daughters and a son,[2] Gordon Laybourne Smith, who ultimately followed his father into architecture.[34]

Laybourne Smith "consistently overworked";[2] architecture was said to be both his profession and his obsession.[33] When his firm announced a retirement scheme he declared that he had no intention of retiring, and such proved to be the case—he died at his desk on 13 September 1965 at the age of 85.[15]

Notes

- ↑ Louis Laybourne Smith School of Architecture & Design, UniSA.edu.au

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Irwin 2006

- 1 2 Page 1986, p. 108

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sullivan Architect Personal Details

- ↑ Louis Laybourne Smith, cited in Page 1986, p. 108

- ↑ Page 1986, p. 108. Page notes that during this period in South Australia, aspiring architects were articled to a practitioner for a fee, rather than studying the field through the education system. The first formal architecture course wasn't offered until 1906 under Laybourne Smith's direction, although according to Collins, Ibels and Garnaut, there were some architectural subjects taught in the 1880s at the School of Design (2005, p. 30).

- ↑ Page 1986, pp. 108–109

- 1 2 3 4 Garnaut 2006

- 1 2 3 Page 1986, p. 109

- ↑ Irwin 2006. There are some inconsistencies about the date of completion – Irwin places it in 1911, while Garnaut (2006) reports that his degree was completed in 1908.

- 1 2 Collins, Ibels and Garnaut 2005, p. 31

- ↑ H. Fuller cited in Collins, Ibels and Garnaut 2005, p. 31

- ↑ Last 1986, pp. 70, 74

- ↑ Page 1986, p. 111 In 1930 Woods, Bagot, Jory & Laybourne Smith became Woods, Bagot, Laybourne Smith & Irwin, after the departure of Herbert Jory, while today the firm is known simply as Woods Bagot.

- 1 2 Page 1986, p. 217

- 1 2 3 4 5 Page 1986, p. 166

- ↑ Collins, Ibels and Garnaut 2005, p. 32

- 1 2 Page 1986, p. 144

- ↑ Page 1986, pp. 146

- ↑ Ward July 2004 While some of Laybourne Smith's work remains, the site was extensively redeveloped in the 1960s and 1970s by Newell Platten and Robert Dickson.

- ↑ "St Cuthbert's Anglican Church (listing SA14045)". Australia Heritage Places Inventory. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ "Cabra Convent Chapel (entry AHD6555)". Australian Heritage Database. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- 1 2 "Office (former AMP Building) (listing SA11574)". Australia Heritage Places Inventory. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ↑ "Balfours Shop and Cafe (listing SA10411)". Australia Heritage Places Inventory. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ Richardson 1986, p. 4

- ↑ Page 1986, p. 148

- ↑ Richardson 25 April 1998, p. 10

- ↑ Collins, Ibels and Garnaut 2005, p. 30

- 1 2 Page 1986, p. 137

- 1 2 3 Page 1986, pp. 136–137

- ↑ Page 1986, p. 116

- ↑ Page 1986, p. 217. Page notes that there were plans to mount the bust on a plinth along Adelaide's North Terrace, where a number of other notable South Australian figures are displayed, but the City Council turned down the offer.

- 1 2 Page 1986, p. 149

- ↑ Page 1986, pp. 146, 217. Gordon Laybourne Smith was articled to his father's firm "as soon as he left school", and later became a partner in the company.

References

- Collins, Julie; Ibels, Alexander; Garnaut, Christine (2005). "Years of Significance: South Australian architecture and the Great War". Journal of the Historical Society of South Australia (33). Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Garnaut, Christine (9 August 2006). "Biography of Louis Edouard Laybourne Smith (1880-1965)". Louis Laybourne Smith School of Architecture and Design. University of South Australia. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- Irwin, J. C. (2006). "Smith, Louis Laybourne (1880–1965)". Australian Dictionary of Biography, Online Edition. Australian National University. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- Last, Peter (1994). The Repat: A Biography of Repatriation General Hospital (Daw Park) and a History of Repatriation Services in South Australia. Daw Park, Australia: Repatriation General Hospital. ISBN 0-646-13843-X.

- Page, Michael (1986). Sculptors in Space: South Australian Architects 1836–1986. Adelaide, Australia: The Royal Australian Institute of Architects (South Australian Chapter). ISBN 0-9588233-0-8.

- Richardson, Donald (25 April 1998). "Shaped for eternal honor". The Advertiser.

- Sullivan, Christine. "Architect Personal Details". Architects of South Australia. University of South Australia. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- Ward, Peter (July 2004). "State of the Union good enough for judges". The Adelaide Review. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

Further reading

- Freeland, J.M. The Making of a Profession, Sydney, Angus and Robertson, 1971.

- Walkley, G. The Louis Laybourne Smith School of Architecture & Building, South Australian Institute of Technology: a history, 1906–1976, South Australian Institute of Technology, [Adelaide], 1976.

External links

- 1961 photo of Layboune Smith and the John Dowie bust.

|