Alfred, Lord Tennyson

| The Right Honourable The Lord Tennyson FRS | |

|---|---|

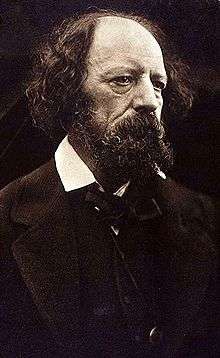

1869 Carbon print by Julia Margaret Cameron | |

| Born |

6 August 1809 Somersby, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died |

6 October 1892 (aged 83) Lurgashall, Sussex, England[1] |

| Occupation | Poet Laureate |

| Alma mater | Cambridge University |

| Spouse | Emily Sellwood (m. 1850) |

| Children |

|

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson, FRS (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was Poet Laureate of Great Britain and Ireland during much of Queen Victoria's reign and remains one of the most popular British poets.[2]

Tennyson excelled at penning short lyrics, such as "Break, Break, Break", "The Charge of the Light Brigade", "Tears, Idle Tears" and "Crossing the Bar". Much of his verse was based on classical mythological themes, such as Ulysses, although In Memoriam A.H.H. was written to commemorate his friend Arthur Hallam, a fellow poet and student at Trinity College, Cambridge, after he died of a stroke aged just 22.[3] Tennyson also wrote some notable blank verse including Idylls of the King, "Ulysses", and "Tithonus". During his career, Tennyson attempted drama, but his plays enjoyed little success. A number of phrases from Tennyson's work have become commonplaces of the English language, including "Nature, red in tooth and claw" (In Memoriam A.H.H.), "'Tis better to have loved and lost / Than never to have loved at all", "Theirs not to reason why, / Theirs but to do and die", "My strength is as the strength of ten, / Because my heart is pure", "To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield", "Knowledge comes, but Wisdom lingers", and "The old order changeth, yielding place to new". He is the ninth most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations.[4]

Early life

Tennyson was born in Somersby, Lincolnshire, England.[5] He was born into a middle-class line of Tennysons, but also had a noble and royal ancestry.

His father, George Clayton Tennyson (1778–1831), was rector of Somersby (1807–1831), also rector of Benniworth (1802–1831) and Bag Enderby, and vicar of Grimsby (1815). Rev. George Clayton Tennyson raised a large family and "was a man of superior abilities and varied attainments, who tried his hand with fair success in architecture, painting, music, and poetry. He was comfortably well off for a country clergyman and his shrewd money management enabled the family to spend summers at Mablethorpe and Skegness, on the eastern coast of England". Alfred Tennyson's mother, Elizabeth Fytche (1781–1865), was the daughter of Stephen Fytche (1734–1799), vicar of St. James Church, Louth (1764) and rector of Withcall (1780), a small village between Horncastle and Louth. Tennyson's father "carefully attended to the education and training of his children".

Tennyson and two of his elder brothers were writing poetry in their teens, and a collection of poems by all three was published locally when Alfred was only 17. One of those brothers, Charles Tennyson Turner, later married Louisa Sellwood, the younger sister of Alfred's future wife; the other was Frederick Tennyson. Another of Tennyson's brothers, Edward Tennyson, was institutionalised at a private asylum.

Education and first publication

Tennyson was a student of Louth Grammar School for four years (1816–1820)[6] and then attended Scaitcliffe School, Englefield Green and King Edward VI Grammar School, Louth. He entered Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1827, where he joined a secret society called the Cambridge Apostles.[7] A portrait of Tennyson by George Frederic Watts is in Trinity's collection.[8]

At Cambridge, Tennyson met Arthur Henry Hallam and William Henry Brookfield, who became his closest friends. His first publication was a collection of "his boyish rhymes and those of his elder brother Charles" entitled Poems by Two Brothers published in 1827.[6]

In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his first pieces, "Timbuktu".[9][10] Reportedly, "it was thought to be no slight honour for a young man of twenty to win the chancellor's gold medal".[6] He published his first solo collection of poems, Poems Chiefly Lyrical in 1830. "Claribel" and "Mariana", which later took their place among Tennyson's most celebrated poems, were included in this volume. Although decried by some critics as overly sentimental, his verse soon proved popular and brought Tennyson to the attention of well-known writers of the day, including Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Return to Lincolnshire and second publication

In the spring of 1831, Tennyson's father died, requiring him to leave Cambridge before taking his degree. He returned to the rectory, where he was permitted to live for another six years, and shared responsibility for his widowed mother and the family. Arthur Hallam came to stay with his family during the summer and became engaged to Tennyson's sister, Emilia Tennyson.

In 1833 Tennyson published his second book of poetry, which included his well-known poem, "The Lady of Shalott". The volume met heavy criticism, which so discouraged Tennyson that he did not publish again for ten years, although he did continue to write. That same year, Hallam died suddenly and unexpectedly after suffering a cerebral haemorrhage while on vacation in Vienna. Hallam's death had a profound impact on Tennyson, and inspired several masterpieces, including "In the Valley of Cauteretz" and In Memoriam A.H.H., a long poem detailing the "Way of the Soul".[11]

Tennyson and his family were allowed to stay in the rectory for some time, but later moved to High Beach, Essex, about 1837, leaving in 1840.[12] An unwise investment in an ecclesiastical wood-carving enterprise soon led to the loss of much of the family fortune. Tennyson then moved to London, and lived for a time at Chapel House, Twickenham.

Third publication

In 1842 while living modestly in London, Tennyson published two volumes of Poems, of which the first included works already published and the second was made up almost entirely of new poems. They met with immediate success. Poems from this collection, such as Locksley Hall, "Tithonus", and "Ulysses" have met enduring fame. The Princess: A Medley, a satire on women's education, which came out in 1847, was also popular for its lyrics. W. S. Gilbert later adapted and parodied the piece twice: in The Princess (1870) and in Princess Ida (1884).

It was in 1850 that Tennyson reached the pinnacle of his career, finally publishing his masterpiece, In Memoriam A.H.H., dedicated to Hallam. Later the same year he was appointed Poet Laureate, succeeding William Wordsworth. In the same year (on 13 June), Tennyson married Emily Sellwood, whom he had known since childhood, in the village of Shiplake. They had two sons, Hallam Tennyson (b. 11 August 1852)—named after his friend—and Lionel (b. 16 March 1854).

Tennyson rented Farringford House on the Isle of Wight in 1853, and then bought it in 1856.[13] He eventually found that there were too many starstruck tourists who pestered him in Farringford, so he moved to Aldworth, in West Sussex in 1869.[14] However, he retained Farringford, and regularly returned there to spend the winters.

Poet Laureate

In 1850, after William Wordsworth's death and Samuel Rogers' refusal, Tennyson was appointed to the position of Poet Laureate; Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Leigh Hunt had also been considered.[15] He held the position until his own death in 1892, by far the longest tenure of any laureate before or since. Tennyson fulfilled the requirements of this position by turning out appropriate but often uninspired verse, such as a poem of greeting to Princess Alexandra of Denmark when she arrived in Britain to marry the future King Edward VII. In 1855, Tennyson produced one of his best-known works, "The Charge of the Light Brigade", a dramatic tribute to the British cavalrymen involved in an ill-advised charge on 25 October 1854, during the Crimean War. Other esteemed works written in the post of Poet Laureate include Ode on the Death of the Duke of Wellington and Ode Sung at the Opening of the International Exhibition.

Tennyson initially declined a baronetcy in 1865 and 1868 (when tendered by Disraeli), finally accepting a peerage in 1883 at Gladstone's earnest solicitation. In 1884 Victoria created him Baron Tennyson, of Aldworth in the County of Sussex and of Freshwater in the Isle of Wight.[16] He took his seat in the House of Lords on 11 March 1884.[6]

Tennyson also wrote a substantial quantity of unofficial political verse, from the bellicose "Form, Riflemen, Form", on the French crisis of 1859 and the Creation of the Volunteer Force, to "Steersman, be not precipitate in thine act/of steering", deploring Gladstone's Home Rule Bill.

Virginia Woolf wrote a play called Freshwater, showing Tennyson as host to his friends Julia Margaret Cameron and G.F. Watts.[17]

Tennyson was the first to be raised to a British peerage for his writing. A passionate man with some peculiarities of nature, he was never particularly comfortable as a peer, and it is widely held that he took the peerage in order to secure a future for his son Hallam.

Thomas Edison made sound recordings of Tennyson reading his own poetry, late in his life. They include recordings of The Charge of the Light Brigade, and excerpts from "The splendour falls" (from The Princess), "Come into the garden" (from Maud), "Ask me no more", "Ode on the death of the Duke of Wellington", "Charge of the Light Brigade", and "Lancelot and Elaine"; the sound quality is as poor as wax cylinder recordings usually are.

Towards the end of his life Tennyson revealed that his "religious beliefs also defied convention, leaning towards agnosticism and pandeism":[18] Famously, he wrote in In Memoriam: "There lives more faith in honest doubt, believe me, than in half the creeds." [The context directly contradicts the apparent meaning of this quote.] In Maud, 1855, he wrote: "The churches have killed their Christ". In "Locksley Hall Sixty Years After," Tennyson wrote: "Christian love among the churches look'd the twin of heathen hate." In his play, Becket, he wrote: "We are self-uncertain creatures, and we may, Yea, even when we know not, mix our spites and private hates with our defence of Heaven". Tennyson recorded in his Diary (p. 127): "I believe in Pantheism of a sort". His son's biography confirms that Tennyson was not an orthodox Christian, noting that Tennyson praised Giordano Bruno and Spinoza on his deathbed, saying of Bruno, "His view of God is in some ways mine", in 1892.[19]

Tennyson continued writing into his eighties. He died on 6 October 1892 at Aldworth, aged 83. He was buried at Westminster Abbey. A memorial was erected in All Saints' Church, Freshwater. His last words were; "Oh that press will have me now!".[20] He left an estate of £57,206.[21]

He was succeeded as 2nd Baron Tennyson by his son, Hallam, who produced an authorised biography of his father in 1897, and was later the second Governor-General of Australia.

Tennyson and the Queen

Though Prince Albert was largely responsible for Tennyson's appointment as Laureate,[15] Queen Victoria became an ardent admirer of Tennyson's work, writing in her diary that she was "much soothed & pleased" by reading In Memoriam A.H.H. after Albert's death.[22] The two met twice, first in April 1862, when Victoria wrote in her diary, "very peculiar looking, tall, dark, with a fine head, long black flowing hair & a beard, — oddly dressed, but there is no affectation about him."[23] Tennyson met her a second time nearly two decades later, and the Queen told him what a comfort In Memoriam A.H.H. had been.[24]

The art of Tennyson's poetry

As source material for his poetry, Tennyson used a wide range of subject matter ranging from medieval legends to classical myths and from domestic situations to observations of nature. The influence of John Keats and other Romantic poets published before and during his childhood is evident from the richness of his imagery and descriptive writing.[25] He also handled rhythm masterfully. The insistent beat of Break, Break, Break emphasises the relentless sadness of the subject matter. Tennyson's use of the musical qualities of words to emphasise his rhythms and meanings is sensitive. The language of "I come from haunts of coot and hern" lilts and ripples like the brook in the poem and the last two lines of "Come down O maid from yonder mountain height" illustrate his telling combination of onomatopoeia, alliteration, and assonance:

- The moan of doves in immemorial elms

- And murmuring of innumerable bees.

Tennyson was a craftsman who polished and revised his manuscripts extensively, to the point where his efforts at self-editing were described by his contemporary Robert Browning as "insane", symptomatic of "mental infirmity".[26] Few poets have used such a variety of styles with such an exact understanding of metre; like many Victorian poets, he experimented in adapting the quantitative metres of Greek and Latin poetry to English.[27] He reflects the Victorian period of his maturity in his feeling for order and his tendency towards moralising. He also reflects a concern common among Victorian writers in being troubled by the conflict between religious faith and expanding scientific knowledge.[28] Like many writers who write a great deal over a long time, his poetry is occasionally uninspired, but his personality rings throughout all his works – work that reflects a grand and special variability in its quality. Tennyson possessed the strongest poetic power, which his early readers often attributed to his "Englishness" and his masculinity.[29] He put great length into many works, most famous of which are Maud and Idylls of the King, the latter arguably the most famous Victorian adaptation of the legend of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. A common thread of grief, melancholy, and loss connects much of his poetry (e.g., Mariana, The Lotos Eaters, Tears, Idle Tears, In Memoriam), likely reflecting Tennyson's own lifelong struggle with debilitating depression.[30] T. S. Eliot famously described Tennyson as "the saddest of all English poets", whose technical mastery of verse and language provided a "surface" to his poetry's "depths, to the abyss of sorrow".[31] Other poets such as W. H. Auden maintained a more critical stance, stating that Tennyson was the "stupidest" of all the English poets, adding that: "There was little about melancholia he didn't know; there was little else that he did."[32]

Partial list of works

- From Poems, Chiefly Lyrical (1830):

- Nothing Will Die [33]

- All Things Will Die [34]

- The Dying Swan

- The Kraken

- Mariana

- Lady Clara Vere de Vere (1832)

- From Poems (1833):

- The Lotos-Eaters

- The Lady of Shalott (1832, 1842) – three versions painted by J. W. Waterhouse (1888, 1894, and 1916). Also put to music by Loreena McKennitt on her album The Visit (1991).

- St. Simeon Stylites (1833)

- From Poems (1842):

- Locksley Hall

- Tithonus

- Vision of Sin [35]

- The Two Voices (1834)

- "Ulysses" (1833)

- From The Princess; A Medley (1847)

- "The Princess"

- Godiva

- Now Sleeps the Crimson Petal – it later appeared as a song in the film Vanity Fair, with musical arrangement by Mychael Danna

- "Tears, Idle Tears"

- In Memoriam A.H.H. (1849)

- Ring Out, Wild Bells (1850)

- The Eagle (1851)

- The Sister's Shame[36]

- From Maud; A Monodrama (1855/1856)

- Maud

- The Charge of the Light Brigade (1854) – an early recording exists of Tennyson reading this.

- From Enoch Arden and Other Poems (1862/1864)

- Enoch Arden

- The Brook – contains the line "For men may come and men may go, But I go on for ever" which inspired the naming of a men's club in New York City.

- Flower in the crannied wall (1869)

- The Window – Song cycle with Arthur Sullivan. (1871)

- Harold (1876) – began a revival of interest in King Harold

- Idylls of the King (composed 1833–1874)

- "Becket" (1884) [37]

- Crossing the Bar (1889)

- The Foresters – a play with incidental music by Arthur Sullivan (1891)

- Kapiolani (published after his death by Hallam Tennyson)[38]

Tennyson heraldry

An Heraldic achievement of Alfred, Lord Tennyson exists in an 1884 stained glass window in the Hall of Trinity College, Cambridge, showing arms: Gules, a bend nebuly or thereon a chaplet vert between three leopard's faces jessant-de-lys of the second; Crest: A dexter arm in armour the hand in a gauntlet or grasping a broken tilting spear enfiled with a garland of laurel; Supporters: Two leopards rampant guardant gules semée de lys and ducally crowned or; Motto: Respiciens Prospiciens[39] ("Looking backwards (is) looking forwards"). These are a difference of the arms of Thomas Tenison (1636-1715), Archbishop of Canterbury, themselves a difference of the arms of the 13th century Denys family of Glamorgan and Siston in Gloucestershire, themselves a difference of the arms of Thomas de Cantilupe (c.1218-1282), Bishop of Hereford, thenceforth the arms of the See of Hereford; the name "Tennyson" signifies "Denys's son", although no connection between the two families is recorded.

References

- ↑ "British Listed Buildings – Aldworth House, Lurgashall". British Listed Buildings Online. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ↑ "Ten of the greatest: British poets". Mail on Sunday. Retrieved 6 November 2012

- ↑ Stern, Keith (2007). Queers In History (2007 ed.). Quistory Publishers.

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. 1999.

- ↑ Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Brief Biography, Glenn Everett, Associate Professor of English, University of Tennessee at Martin

- 1 2 3 4 Poems of Alfred Lord Tennyson. Eugene Parsons (Introduction). New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1900.

- ↑ "Tennyson, Alfred (TNY827A)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ "Trinity College, University of Cambridge". BBC Your Paintings.

- ↑ Friedlander, Ed. "Enjoying "Timbuktu" by Alfred Tennyson"

- ↑ "Alfred, Lord Tennyson 1809 – 1892". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved on 27 October 2007.

- ↑ H. Tennyson, Alfred Lord Tennyson: A Memoir by His Son, New York, MacMillan, 1897.

- ↑ "History of Holy Innocents Church", Highbeachchurch.org. Retrieved 27 April 2012

- ↑ The Home of Tennyson, Rebecca FitzGerald, Farringford: The Home of Tennyson official website

- ↑ Good Stuff. "Aldworth House - Lurgashall - West Sussex - England - British Listed Buildings". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk.

- 1 2 Batchelor, John. Tennyson: To Strive, To Seek, To Find. London: Chatto and Windus, 2012.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 25308. p. 243. 15 January 1884.

- ↑ "primaveraproductions.com". primaveraproductions.com.

- ↑ Cambridge Book and Print Gallery

- ↑ Freethought of the Day, 6 August 2006, Alfred Tennyson

- ↑ Andrew Motion, BBC Radio 4, "Great Lives: Alfred, Lord Tennyson", broadcast on 4 August 2009

- ↑ Christopher Ricks Tennyson Macmillan 1972 p.236

- ↑ "Queen Victoria's Journals - Information Site". queenvictoriasjournals.org. January 5, 1862.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria's Journals - Information Site". queenvictoriasjournals.org. April 14, 1862.

- ↑ "Queen Victoria's Journals - Information Site". queenvictoriasjournals.org. August 7, 1883.

- ↑ Grendon, Felix (July 1907). "The Influence of Keats upon the Early Poetry of Tennyson". The Sewanee Review 15 (3): 285–296. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Baker, John Haydn (2004). Browning and Wordsworth. Cranbury NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 10. ISBN 0838640389. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Pattison, Robert (1979). Tennyson and Tradition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 106. ISBN 0674874153. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Gossin, Pamela (2002). Encyclopedia of Literature and Science. Westport CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 461. ISBN 0313305382. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ↑ Sherwood, Marion (2013). Tennyson and the Fabrication of Englishness. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 69–70. ISBN 1137288892. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ↑ Riede, David G. (2000). "Tennyson's Poetics of Melancholy and the Imperial Imagination". Studies in English Literature 40 (4): 659–678. doi:10.1353/sel.2000.0040.

- ↑ T. S. Eliot, Selected Prose of T. S. Eliot. Ed. Frank Kermode. New York: Harcourt, 1975. P. 246.

- ↑ Carol T. Christ, Catherine Robson, The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume E: The Victorian Age. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt & M.H. Abrams. New York: Norton, 2006. P.1111

- ↑ The Bitmill Inc. "Nothing Will Die". litscape.com.

- ↑ The Bitmill Inc. "All Things Will Die". litscape.com.

- ↑ Vision of Sin

- ↑ "Poetry Lovers' Page: Alfred Lord Tennyson". poetryloverspage.com.

- ↑ "Becket and other plays by Baron Alfred Tennyson Tennyson - Free Ebook". gutenberg.org. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ↑ Alfred Lord Tennyson (1899). Hallam Tennyson, ed. The life and works of Alfred Lord Tennyson 8. Macmillan. pp. 261–263.

- ↑ Debrett's Peerage, 1968, p.1091

Bibliography

- Alfred, Lord Tennyson Tennyson: A Selected Edition (California: University of California Press, 1989) ISBN 0-520-06588-3 (hbk.) or ISBN 0-520-06666-9 (pbk.) Edited with a preface and notes by Christopher Ricks. Selections from the definitive edition The Poems of Tennyson, with readings from the Trinity MSS; long works like Maud and In Memoriam A. H. H. are printed in full.

External links

- Leslie, Stephen (1898). "Life of Tennyson". Studies of a Biographer 2. London: Duckworth and Co. pp. 196–240.

- "Tennyson", a poem by Florence Earle Coates

- Tennyson's Grave, Westminster Abbey

- Poems by Alfred Tennyson

- Tennyson index entry at Poets' Corner

- Biography & Works (public domain)

- Online copy of Locksley Hall

- Selected Poems of A. Tennyson

- The Twickenham Museum – Alfred Lord Tennyson in Twickenham

- Farringford Holiday Cottages and Restaurant, Home of Tennyson, Isle of Wight

- Tennyson in Twickenham

- Works by Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Alfred, Lord Tennyson at Internet Archive

- Works by Alfred, Lord Tennyson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Settings of Alfred Tennyson's poetry in the Choral Public Domain Library

- The Louverture Project: Anacaona – poem by Alfred Tennyson – Poem about the Taíno queen.

- Selected Works at Poetry Index

- Sweet and Low

- Recording of Tennyson reciting "The Charge of the Light Brigade"

- Anonymous (1873). Cartoon portraits and biographical sketches of men of the day. Illustrated by Frederick Waddy. London: Tinsley Brothers. pp. 78–84. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- A substantial collection of Tennyson's works are held at Special Collections and Archives, Cardiff University.

| Court offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by William Wordsworth |

British Poet Laureate 1850–1892 |

Succeeded by Alfred Austin |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New title | Baron Tennyson 1884–1892 |

Succeeded by Hallam Tennyson |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||

|