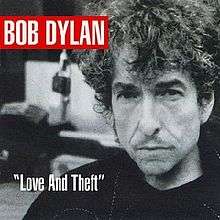

Love and Theft (Bob Dylan album)

| "Love and Theft" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Bob Dylan | ||||

| Released | September 11, 2001 | |||

| Recorded | May 2001 | |||

| Genre | Folk rock, blues rock, country blues, roots rock, electric blues, Americana | |||

| Length | 57:25 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Jack Frost (Bob Dylan's pseudonym) | |||

| Bob Dylan chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Love And Theft" (generally referred to as Love and Theft) is the thirty-first studio album by American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, released on September 11, 2001 by Columbia Records. It featured backing by his touring band of the time, with keyboardist Augie Meyers added for the sessions. It peaked at #5 on the Billboard 200, and has been certified with a gold album by the RIAA.[1] A limited edition release included two bonus tracks on a separate disc recorded in the early 1960s, and two years later, on September 16, 2003, this album was one of fifteen Dylan titles reissued and remastered for SACD hybrid playback.

Content

The album continued Dylan's artistic comeback following 1997's Time Out of Mind and was given an even more enthusiastic reception. The title of the album was apparently inspired by historian Eric Lott's book Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, which was published in 1993. "Love and Theft becomes his Fables of the Reconstruction, to borrow an R.E.M. album title", writes Greg Kot in The Chicago Tribune (published September 11, 2001), "the myths, mysteries and folklore of the South as a backdrop for one of the finest roots rock albums ever made."

The opening track, "Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum", includes many references to parades in Mardi Gras in New Orleans, where participants are masked, and "determined to go all the way" of the parade route, in spite of being intoxicated. "It rolls in like a storm, drums galloping over the horizon into ear shot, guitar riffs slicing with terse dexterity while a tale about a pair of vagabonds unfolds," writes Kot. "It ends in death, and sets the stage for an album populated by rogues, con men, outcasts, gamblers, gunfighters and desperados, many of them with nothing to lose, some of them out of their minds, all of them quintessentially American.

They're the kind of twisted, instantly memorable characters one meets in John Ford's westerns, Jack Kerouac's road novels, but, most of all, in the blues and country songs of the 1920s, '30s and '40s. This is a tour of American music—jump blues, slow blues, rockabilly, Tin Pan Alley ballads, Country Swing—that evokes the sprawl, fatalism and subversive humor of Dylan's sacred text, Harry Smith's Anthology of American Folk Music, the pre-rock voicings of Hank Williams, Charley Patton and Johnnie Ray, among others, and the ultradry humor of Groucho Marx.

Offered the song by Dylan, Sheryl Crow later recorded an up-tempo cover of "Mississippi" for her The Globe Sessions, released in 1998, before Dylan revisited it for Love and Theft. Subsequently the Dixie Chicks made it a mainstay of their Top of the World, Vote for Change, and Accidents & Accusations Tours.

As music critic Tim Riley notes, "[Dylan's] singing [on Love and Theft] shifts artfully between humble and ironic...'I'm not quite as cool or forgiving as I sound,' he sings in 'Floater,' which is either hilarious or horrifying, and probably a little of both."[2]

"Love and Theft is, as the title implies, a kind of homage," writes Kot, "[and] never more so than on 'High Water (for Charley Patton),' in which Dylan draws a sweeping portrait of the South's racial history, with the unsung blues singer as a symbol of the region's cultural richness and ingrained social cruelties. Rumbling drums and moaning backing vocals suggest that things are going from bad to worse. 'It's tough out there,' Dylan rasps. 'High water everywhere.' Death and dementia shadow the album, tempered by tenderness and wicked gallows humor."

"'Po Boy', scored for guitar with lounge chord jazz patterns, 'almost sounds as if it could have been recorded around 1920," says Riley. "He leaves you dangling at the end of each bridge, lets the band punctuate the trail of words he's squeezed into his lines, which gives it a reluctant soft-shoe charm."

In a critique, "A missed work of genius", Tony Attwood compares the lyrics of "Honest With Me" with Dylan's 1965 song "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues", concluding that the former song is "utter brilliance"[3]

The album closes with "Sugar Baby", a lengthy, dirge-like ballad, noted for its evocative, apocalyptic imagery and sparse production drenched in echo. Praising it as "a finale to be proud of," Riley notes that "Sugar Baby" is "built on a disarmingly simple riff that turns foreboding."

Recording

This album has been incorrectly cited as being recorded digitally into Pro Tools. This album was recorded to a Studer A800 mkIII @ 30ips on BASF/Emtec 900 tape at +6/250 nanowebers per meter. Pro Tools was used solely for editing of specific tracks and was thus used very sparingly. Whatever work was done in Pro Tools was flown right back to the 2-inch (51 mm) masters. It was mixed from the 2-inch (51 mm) masters to an Ampex ATR-102 1-inch 2-track customized by Mark Spitz at ATR Services.

In an interview conducted by Alan Jackson for The Times Magazine in 2001, before the album was released, Dylan said "these so-called connoisseurs of Bob Dylan music...I don't feel they know a thing, or have any inkling of who I am and what I’m about. I know they think they do, and yet it’s ludicrous, it's humorous, and sad. That such people have spent so much of their time thinking about who? Me? Get a life, please. It’s not something any one person should do about another. You’re not serving your own life well. You’re wasting your life."

Reception

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Aggregate scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 93/100[4] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A–[7] |

| The Guardian | |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| PopMatters | 9/10[10] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Spin | 9/10[13] |

| The Village Voice | A+[14] |

In a glowing review for his "Consumer Guide" column published by The Village Voice, Robert Christgau wrote: "If Time Out of Mind was his death album—it wasn't, but you know how people talk—this is his immortality album."[14] Later, when The Village Voice conducted its annual Pazz & Jop Critics Poll, Love and Theft topped the list, the third Dylan album to accomplish this.[15] It also topped Rolling Stone's list.[16] Q listed Love and Theft as one of the best 50 albums of 2001.[17] Kludge ranked it at number eight on their list of best albums of 2001.[18]

In 2012, the album was ranked #385 on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, while Newsweek magazine pronounced it the second best album of its decade.[19] In 2009, Glide Magazine ranked it as the #1 Album of the Decade.[20] Entertainment Weekly put it on its end-of-the-decade, "best-of" list, saying, "The predictably unpredictable rock poet greeted the new millennium with a folksy, bluesy instant classic."[21]

The album won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Folk Album at the 44th Annual Grammy Awards. It was nominated for Album of the Year and the track "Honest with Me" was nominated for Best Male Rock Vocal Performance.

Chart positions

| Year | Chart | Position |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Billboard 200 | 5[22] |

Allegations of plagiarism

"Love and Theft" generated controversy when some similarities between the album's lyrics to Japanese writer Junichi Saga's book Confessions of a Yakuza were pointed out.[23][24] Translated to English by John Bester, the book was a biography of one of the last traditional Yakuza bosses in Japan. In the article published in the Journal, a line from "Floater" ("I'm not quite as cool or forgiving as I sound") was traced to a line in the book, which said "I'm not as cool or forgiving as I might have sounded." Another line from "Floater" is "My old man, he's like some feudal lord." On the first lines of the book is the line "My old man would sit there like a feudal lord." However, when informed of this, author Saga's reaction was one of having been honored rather than abused from Dylan's use of lines from his work.[25]

Track listing

All songs written and composed by Bob Dylan.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum" | 4:46 |

| 2. | "Mississippi" | 5:21 |

| 3. | "Summer Days" | 4:52 |

| 4. | "Bye and Bye" | 3:16 |

| 5. | "Lonesome Day Blues" | 6:05 |

| 6. | "Floater (Too Much to Ask)" | 4:59 |

| 7. | "High Water (For Charley Patton)" | 4:04 |

| 8. | "Moonlight" | 3:23 |

| 9. | "Honest with Me" | 5:49 |

| 10. | "Po' Boy" | 3:05 |

| 11. | "Cry a While" | 5:05 |

| 12. | "Sugar Baby" | 6:40 |

Total length: |

57:25 | |

| Limited edition bonus disc digipack release | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | "I Was Young When I Left Home" (Recorded December 22, 1961) | 5:24 |

| 2. | "The Times They Are a-Changin'" (Alternate version, recorded October 23, 1963[26]) | 2:56 |

Total length: |

8:20 | |

Personnel

- Bob Dylan — vocals, guitar, piano, record production

- Larry Campbell — guitar, banjo, mandolin, violin

- Charlie Sexton — guitar

- Augie Meyers — accordion, Hammond B3 organ, Vox organ

- Tony Garnier — bass

- David Kemper — drums

- Clay Meyers — bongos

- Chris Shaw — engineering

References

- ↑ RIAA website retrieved 03-12-10. Archived 2 September 2008 at WebCite

- ↑ Public Arts review

- ↑ http://bob-dylan.org.uk/archives/329

- ↑ "Reviews for Love and Theft by Bob Dylan". Metacritic. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ↑ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Love and Theft – Bob Dylan". AllMusic. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Wolk, Douglas. ""Love and Theft"". Blender. Archived from the original on June 30, 2006. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Browne, David (September 10, 2001). "Love and Theft". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Petridis, Alex (September 7, 2001). "One for the Bobcats". The Guardian. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Hilburn, Robert (September 9, 2001). "This Year's Dylan Is a Sonic Dynamo". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Stephens, Michael (September 11, 2001). "Bob Dylan: "Love and Theft"". PopMatters. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ "Bob Dylan: "Love and Theft"". Q (182): 122. October 2001.

- ↑ Sheffield, Rob (September 27, 2001). "Love and Theft". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ Light, Alan (November 2001). "The Jack of Hearts". Spin 17 (11): 127–28. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- 1 2 Christgau, Robert (September 18, 2001). "Consumer Guide: Minstrels All". The Village Voice. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ↑ "Pazz & Jop 2001: Album Winners". The Village Voice. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ↑ Fricke, David (December 27, 2001). "The Year in Recordings: The Top 10 Albums of the Year 2001". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved March 28, 2014.

- ↑ "The Best 50 Albums of 2001". Q. December 2001. pp. 60–65.

- ↑ Perez, Arturo. "Top 10 Albums of 2001". Kludge. Archived from the original on July 22, 2004. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ↑ "#2 'Love and Theft' Bob Dylan". Newsweek. 2009-12-11. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 2009-12-27.

- ↑ "Glide's Best Albums of the Decade" Archived October 29, 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Geier, Thom; Jensen, Jeff; Jordan, Tina; Lyons, Margaret; Markovitz, Adam; Nashawaty, Chris; Pastorek, Whitney; Rice, Lynette; Rottenberg, Josh; Schwartz, Missy; Slezak, Michael; Snierson, Dan; Stack, Tim; Stroup, Kate; Tucker, Ken; Vary, Adam B.; Vozick-Levinson, Simon; Ward, Kate (December 11, 2009), "THE 100 Greatest MOVIES, TV SHOWS, ALBUMS, BOOKS, CHARACTERS, SCENES, EPISODES, SONGS, DRESSES, MUSIC VIDEOS, AND TRENDS THAT ENTERTAINED US OVER THE PAST 10 YEARS". Entertainment Weekly. (1079/1080):74-84

- ↑ Allmusic website

- ↑ This is a reprint of an article from The Wall Street Journal as cited in next footnote."Did Bob Dylan Lift Lines From Dr Saga?". California State University, Dear Habermas. 2003-07-08. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ↑ "Did Bob Dylan Lift Lines From Dr Saga?". Wall Street Journal. 2003-07-08. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ↑ Wilentz, Sean. Bob Dylan in America. ISBN 978-0-385-52988-4, p. 310.

- ↑ Bjorner (January 25, 2002) New York City, New York, October 23, 1963 Bjorner's Still on the Road. Retrieved August 27, 2010