Land clearing in Australia

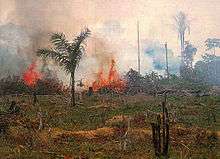

Land clearing in Australia describes the removal of native vegetation and deforestation in Australia. Land clearing involves the removal of native vegetation and habitats, including the bulldozing of native bushlands, forests, savannah, woodlands and native grasslands and the draining of natural wetlands for replacement with agriculture, urban and other land uses.

As much as 70% of Australia's native vegetation has been cleared or modified in the past 200 years, most of which has occurred in the last 50 years. Prior to European settlement native vegetation covered most of Australia but now only 87% of Australia's natural vegetation remains. This 13% of Australia's nativepoos and woodlands.[2]

By region

Tasmania

Tasmanian (in Australia) ancient and unique temperate rainforest areas, were in the danger of being converted into wood plantations for Japanese paper factories In 2007. The swamp gum tree or Tasmanian Oak (Eucalyptus regnans) is the world’s largest flowering plant and the tallest hardwood tree in the world.[3]

Reasons

Agriculture

The primary motivator for land clearing in Australia is agricultural production. Where soil fertility and rainfall allow, the clearing of land allows for increased agricultural production and increase in land values. Land clearing was seen as progressive, and there was the general view that land was wasted unless it was developed.

Historically, land clearing has been supported by the Commonwealth and State Governments as an essential part of improved productivity essential for national economic prosperity. A range of institutional incentives for agriculture increased the economic gain from land clearing, with offerings of cheap land along with venture capital in the form of loans or tax concessions. Other incentives included the War Service Land Settlement Scheme, low interest bank loans and financial support programs such as drought relief assistance.

The majority of cleared land in Australia has been developed for cattle, sheep and wheat production. 46.3% of Australia is used for cattle grazing on marginal semi-deserts with natural vegetation. This land is too dry and infertile for any other agricultural use (apart from some kangaroo culling). Some of this grazing land has been cleared of "woody scrub". 15% of Australia is currently in use for all other agriculture and forestry purposes on mostly cleared land. In New South Wales, much of the remaining forests and woodlands have been cleared, due to the high productivity of the land. Urban development is also the cause of some land clearing, though not a major driver. In The Australian Capital Territory for example, much urban development has occurred on previously cleared agricultural land.

Bushfires in Australia

Bushfires in Australia are frequently occurring events during the hotter months of the year.

Effects

Land clearing destroys plants and local ecosystems and removes the food and habitat on which other native species rely. Clearing allows weeds and invasive animals to spread, affects greenhouse gas emissions and can lead to soil degradation, such as erosion and salinity, which in turn can affect water quality.

The following table shows the Native Vegetation Inventory Assessment (NVIS)[2] of native vegetation by type prior to European settlement and as at 2001-2004.

| Vegetation Type | Pre Settlement Total | 2005 Total | Percentage lost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forest and Woodland | 4,101,868 | 3,184,260 | 22% |

| Shrublands | 1,470,614 | 1,411,539 | 4% |

| Heath | 9,256 | 8,071 | 13% |

| Grassland | 1,996,688 | 1,958,671 | 2% |

| Total Native Vegetation | 7,578,204 | 6,562,541 | 13% |

Effects Land Condition As land cover is crucial to land condition, land clearing exerts significant pressure on land condition. Removal of vegetation also leaves soil bare and vulnerable to erosion. Soil stability is essential to avoid land degradation.

Soil erosion

Soil erosion is a very significant pressure on land condition because it undermines existing vegetation and habitats and inhibits vegetation and other biota that inhabit the vegetation from re-establishing. Terrestrial vegetation is a source of nutrient replenishment for soils. If vegetation is removed, there is less biological matter available to break down and replenish the nutrients in the soil. Exposing soil to erosion leads to further nutrient depletion.

Salinity

Another consequence of land clearing is dryland salinity. Dryland salinity is the movement of salt to the land surface via groundwater. In Australia there are vast amounts of salt stored beneath the land surface. Much of Australian native vegetation has adapted to low rainfall conditions, and use deep root systems to take advantage of any available water beneath the surface. These help to store salt in the earth, by keeping ground water levels low enough so that salt is not pushed to the surface. However, with land clearing, the reduced amount of water that previously got pumped up by the roots of the trees means that the water table rises towards the surface, dissolving salt in the process. Salinity reduces plant productivity and affects the health of rivers and streams.

Biodiversity

The extinction of 108 different species (2 mammal, 9 bird and 97 plant species) has been partially attributed to land clearing. While land condition is one indicator of the pressure of vegetation removal, the health and resilience of the vegetation that remains is also largely dependent on the size of the fragments and their distance from each other. This is also true for species living within these habitat fragments. The smaller and more isolated the remnants, the greater the threat from external pressures as their boundaries (or edges) are more exposed to disturbances. Pressure also increases with the distance between fragments.

Climate change

Land clearing is a major source of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions, contributing approximately 12 percent to Australia’s total emissions in 1998. It has also been found that past clearing of native vegetation contributed to higher temperatures, decreased rainfall and more intense droughts. The removal of vegetation damages the microclimate by removing shade and reducing humidity. It also contributes to global climate change by diminishing the capacity of the vegetation to absorb carbon dioxide. Land clearing could also be responsible for reduced rainfall levels & possible desertification of land as well as soil erosion.

Deforestation and climate extremes

Deo et al. (2009) checked the impacts on climate extremes and droughts by analysing daily rainfall and surface temperature output from the CSIRO Mark 3 GCM. This work, the first of its kind, demonstrated an increase in the number of dry days (<1mm rainfall) and hot days (maximum temperature >35°C), a decrease in daily rainfall intensity and cumulative rainfall on rain days, and an increase in duration of droughts under modified land-cover conditions. These changes were statistically significant for all years across eastern Australia, and especially pronounced during strong El Niño events. Clearly, these studies have demonstrated that LCC has exacerbated the mean climate anomaly and climate extremes in southwest and eastern Australia, thus resulting in longer-lasting and more severe droughts.

Response

Since the 1980s, the rate of land clearing has declined due to changing attitudes and greater awareness of the damaging effects of clearing.

Regulation of clearing.

Clearing is now controlled by legislation in Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria, New South Wales, and to a lesser degree in Queensland. Land clearing controls differ substantially between jurisdictions, and despite growing awareness of the effect of land degradation, controls on clearing have been generally opposed by farmers.

Federal legislation

Land clearing is controlled indirectly by federal law in the form of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth), which may also apply if there are federally protected threatened species (plant or animal) or endangered ecological communities present on the land in question.

New South Wales

Clearing of native vegetation in NSW is regulated by the Native Vegetation Act 2003(NSW), by the protections on the habitat of threatened species contained in the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (NSW) and the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NSW). It is also regulated by development control and Environmental Planning Instruments (EPIs) under land use planning law, namely the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW). Federal law in the form of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) may also apply if there are federally protected threatened species (plant or animal) or endangered ecological communities present on the land in question.

Queensland

Clearing of native vegetation in Queensland is principally regulated by the Vegetation Management Act 1999 and the Vegetation Management (Regrowth Clearing Moratorium) Act 2009. The Federal EPBC Act may also apply (see above).

South Australia

Clearing of native vegetation in SA is principally regulated by the Native Vegetation Act 1991 (SA). The Federal EPBC Act may also apply (see above).

See also

Notes

- ↑ Lamont, Byron B.; Enright, Neal J.; Witkowski, E. T. F.; Groeneveld, J (2007-05-18). "Conservation biology of banksias: insights from natural history to simulation modelling". Australian Journal of Botany (CSIRO Publishing) 55 (3): 280–29. doi:10.1071/BT06024. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - 1 2 Department of Sustainability Environment Water Population and Communities. "Indicator: LD-01 The proportion and area of native vegetation and changes over time". Australian Federal Government. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ↑ Banks, Pulp and People 2007 by Chris Lang June 2007, Urgewald Urgewald.de, pulpmillwatch.org pg.16, 29-31, 45

References

- Australian Greenhouse Office 2000, Land Clearing: A Social History, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Accessed on 29 October 2007.

- Benson, J.S 1991, The effect of 200 years of European settlement on the vegetation and flora of New South Wales, Cunninghamia, 2:343-370.

- Cogger, H, Ford, H, Johnson, C, Holman, J and Butler, D 2003, Impacts of Land Clearing on Australian Wildlife in Queensland, World Wildlife Foundation Australia, Sydney

- Commonwealth Scientific and industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) 2007, Land and Water, www.clw.csiro.au/issues/salinity/faq.html viewed 29 October 2007.

- Department of Environment and Water Resources, State of the Environment Report, viewed 26 October 2007.

- Department of the Environment and Heritage 2005, National Vegetation Information System (NVIS) Stage 1, Version 3.0 Major Vegetation Groups,

- Giles, D 2007, State’s land clearing concern, in The Courier Mail, 28 October 2007.

- National Land and Water Resources Audit, Present Vegetation 1998 in National Land and Water Resources Audit 2001, Commonwealth of Australia, viewed 29 October 2007.

- Thackway, R & Cresswell, I.D (eds.) 1995, An Interim Biogeographic Regionalization for Australia: A Framework for Setting Priorities in the National Reserves System Cooperative Program, Australian Nature Conservation Agency, Canberra.

- The Australian Bureau of Statistics, www.abs.gov.au, viewed 26 October 2007.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||