Erie Canal

| Erie Canal | |

|---|---|

|

Operations at Lockport, New York in 1839 | |

| Specifications | |

| Locks | 36 |

| History | |

| Original owner | New York State |

| Principal engineer | Benjamin Wright |

| Other engineer(s) | Canvass White, Amos Eaton |

| Construction began | July 4, 1817 (at Rome, New York) |

| Date of first use | May 17, 1821 |

| Date completed | October 26, 1825 |

| Date restored | September 4, 1996 |

| Geography | |

| Branch of | New York State Canal System |

| Erie Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

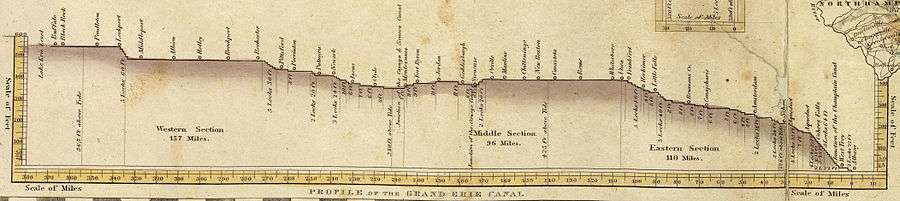

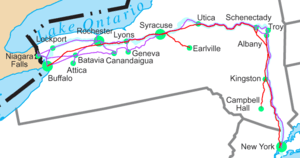

The Erie Canal is a canal in New York that is part of the east-west, cross-state route of the New York State Canal System (formerly known as the New York State Barge Canal). Originally it ran about 363 miles (584 km) from Albany, on the Hudson River to Buffalo, at Lake Erie. It was built to create a navigable water route from New York City and the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Lakes. First proposed in 1807, its construction began in 1817. The canal contains 36 locks and a total elevation differential of about 565 feet (172 m). It opened on October 26, 1825.[1]

In a time when bulk goods were limited to pack animals (an eighth-ton [250 pounds (113 kg)] maximum[2]), and there were no steamships or railways, water was the most cost-effective way to ship bulk goods. The canal was the first transportation system between the eastern seaboard (New York City) and the western interior (Great Lakes) of the United States that did not require portage. It was faster than carts pulled by draft animals, and cut transport costs by about 95%. The canal fostered a population surge in western New York and opened regions farther west to settlement. It was enlarged between 1834 and 1862. The canal's peak year was 1855, when 33,000 commercial shipments took place. In 1918, the western part of the canal was enlarged to become part of the New York State Barge Canal, which ran parallel to the eastern half and extended to the Hudson River.

In 2000, the United States Congress designated the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor[3] to recognize the national significance of the canal system as the most successful and influential human-built waterway and one of the most important works of civil engineering and construction in North America.[3] Mainly used by recreational watercraft since the retirement of the last large commercial ship (rather than boat), the Day Peckinpaugh in 1994, the canal saw a recovery in commercial traffic in 2008.[4]

Background

From the first days of the expansion of the British colonies from the coast of North America into the heartland of the continent, a recurring problem was that of transportation between the coastal ports and the interior. Close to the seacoast, rivers often provided adequate waterways, but the presence of the Appalachian Mountains, 400 miles (640 km) inland, presented a great challenge. Passengers and freight had to travel overland, a journey made more difficult by the rough condition of the roads. In 1800, it typically took 2.5 weeks to travel overland from New York to Cleveland, Ohio [460 miles (740 km)]; 4 weeks to Detroit [612 miles (985 km)].[5]

The principal exportable product of the Ohio Valley was grain, which was a high-volume, low-priced commodity, bolstered by supplies from the coast. Frequently it was not worth the cost of transporting it to far-away population centers. This was a factor leading to farmers in the west turning their grains into whiskey for easier transport and higher sales, and later the Whiskey Rebellion. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, it became clear to coastal residents that the city or state that succeeded in developing a cheap, reliable route to the West would enjoy economic success, and that the port at the seaward end of such a route would see business increase greatly.[6] In time, projects were devised in Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and relatively deep into coastal states.

Proposals and logistics

Proposals

- Early proposals

The successes of the Canal du Midi in France (1681), Bridgewater Canal in Britain (fully completed 1769) and Eiderkanal (superseded by today's Kiel Canal) in Denmark (later Germany) (1784) spurred on what was called in Britain 'canal mania'. The idea of a canal to tie the East Coast to the new western settlements was already in the air by 1724: New York provincial official Cadwallader Colden made a passing reference (in a report on fur trading) to improving the natural waterways of western New York.

Two men, Gouverneur Morris and Elkanah Watson, were early proponents of a canal along the Mohawk River. Their efforts led to the creation of the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company (which took the first steps to improve navigation on the Mohawk), but the company proved that private financing was insufficient.

- Potomac/Patowmack precedent

George Washington led a partly enduring effort to turn the Potomac River into a navigable link to the west, sinking substantial energy and capital into the Patowmack Canal from 1785 until his death fourteen years later.

By 1788 Washington's Potomac Company was successful in constructing five locks which took boats 4,500 feet (1,400 m) past the Potomac Great Falls. The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal superseded the Potomac Canal in 1823.

Christopher Colles (who was familiar with the Bridgewater Canal) surveyed the Mohawk Valley, and made a presentation to the New York state legislature in 1784 proposing a canal from Lake Ontario. The proposal drew attention and some action but was never implemented.

- Scheme

Jesse Hawley finally got the canal built. He had envisioned encouraging the growing of large quantities of grain on the Western New York plains (then largely unsettled) for sale on the Eastern seaboard. However, he went bankrupt trying to ship grain to the coast. While in Canandaigua debtors' prison, Hawley began pressing for the construction of a canal along the 90-mile (140 km)-long Mohawk River valley with support from Joseph Ellicott (agent for the Holland Land Company in Batavia). Ellicott realized that a canal would add value to the land he was selling in the western part of the state. He later became the first canal commissioner.

Engineering requirements

The Mohawk River (a tributary of the Hudson) rises near Lake Ontario and runs in a glacial meltwater channel just north of the Catskill range of the Appalachian Mountains, separating them from the geologically distinct Adirondacks to the north. The Mohawk and Hudson valleys form the only cut across the Appalachians north of Alabama, allowing an almost complete water route from New York City in the south to Lakes Ontario and Erie in the west. Along its course and from these lakes, other Great Lakes, and to a lesser degree, related rivers, a large part of the continent's interior (and many settlements) would be made well connected to the Eastern seaboard.

The problem was that the land rises about 600 feet (180 m) from the Hudson to Lake Erie. Locks at the time could handle up to 12 feet (3.7 m), so even with the heftiest cuttings and viaducts, fifty locks would be required along the 360-mile (580 km) canal. Such a canal would be expensive to build even with modern technology; in 1800, the expense was barely imaginable. President Thomas Jefferson called it "a little short of madness" and rejected it; however, Hawley interested New York Governor DeWitt Clinton in the project. There was much opposition, and the project was ridiculed as "Clinton's folly" and "Clinton's ditch." In 1817, though, Clinton received approval from the legislature for $7 million for construction.[1]

The original canal was 363 miles (584 km) long, from Albany on the Hudson to Buffalo on Lake Erie. The channel was cut 40 feet (12 m) wide and 4 feet (1.2 m) deep, with removed soil piled on the downhill side to form a walkway known as a towpath.[1]

Its construction, through limestone and mountains, proved a daunting task. The canal was built using some of the most advanced engineering technology from Holland. In 1823 construction reached the Niagara Escarpment, necessitating the building of five locks along a 3-mile (4.8 km) corridor to carry the canal over the escarpment. To move earth, animals pulled a "slip scraper" (similar to a bulldozer). The sides of the canal were lined with stone set in clay, and the bottom was also lined with clay. The stonework required hundreds of German masons, who later built many of New York's buildings. All labor on the canal depended upon human (and animal) power or the force of water. Engineering techniques developed during its construction included the building of aqueducts to redirect water; one aqueduct was 950 feet (290 m) long to span 800 feet (240 m) of river. As the canal progressed, the crews and engineers working on the project developed expertise and became a skilled labor force.

Operation

Canal boats up to 3.5 feet (1.1 m) in draft were pulled by horses and mules on the towpath. This canal has one towpath generally on the north side. When canal boats met, the boat with the right of way remained on the towpath side of the canal. The other boat steered toward the berm (or heelpath) side of the canal. The driver (or "hoggee", pronounced HO-gee) of the privileged boat kept his towpath team by the canalside edge of the towpath, while the hoggee of the other boat moved to the outside of the towpath and stopped his team. His towline would be unravelled from the horses, go slack, fall into the water and sink to the bottom while his boat decelerated on with its remaining momentum. The privileged boat's team would step over the other boat's towline with their horses pulling the boat over the sunken towline without stopping. Once clear, the other boat's team would continue on its way.

Construction

The men who planned and oversaw construction were novices, both as surveyors and as engineers. There were no civil engineers in the United States.[7] James Geddes and Benjamin Wright, who laid out the route, were judges whose experience in surveying was in settling boundary disputes. Geddes had only used a surveying instrument for a few hours before his work on the Canal.[7] Canvass White was a 27-year-old amateur engineer who persuaded Clinton to let him go to Britain at his own expense to study the canal system there. Nathan Roberts was a mathematics teacher and land speculator. Yet these men "carried the Erie Canal up the Niagara escarpment at Lockport, maneuvered it onto a towering embankment to cross over Irondequoit Creek, spanned the Genesee River on an awesome aqueduct, and carved a route for it out of the solid rock between Little Falls and Schenectady—and all of those venturesome designs worked precisely as planned". (Bernstein, p. 381)

Construction began July 4, 1817, at Rome, New York. The first 15 miles (24 km), from Rome to Utica, opened in 1819. At that rate the canal would not be finished for 30 years. The main hold-ups were felling trees to clear a path through virgin forest and moving excavated soil, which took longer than expected, but the builders devised way to solve these problems. To fell a tree, they threw rope over the top branches and winched it down. They pulled out the stumps with an innovative stump puller. A pair of huge wheels were mounted loose on an axle. A large wheel, barely smaller than the others, was fixed to the center of the axle. A chain was wrapped around the axle and hooked to the stump. A rope was wrapped around the center wheel and hooked to a team of oxen. The mechanical advantage (torque) obtained ripped the stumps out of the soil. Soil to be moved was shoveled into large wheelbarrows that were dumped into mule-pulled carts. Using a scraper and a plow, a three-man team with oxen, horses, and mules could build a mile in a year.[8]

The remaining problem was finding enough labor, and increased immigration helped fill the need. Many of the laborers working on the canal were Scots Irish, who had recently come to the United States as a group of about 5,000 from Northern Ireland, most of whom were Protestants and wealthy enough to pay for this caravan.

Construction continued at an increased rate as new workers arrived. When the canal reached Montezuma Marsh (at the outlet of Cayuga Lake west of Syracuse), it was rumored that over 1,000 workers died of "swamp fever" (malaria), and construction was temporarily stopped.[9] However, recent research has revealed that the death toll was likely much lower, as no contemporary reports mention significant worker mortality, and mass graves from the period have never been found in the area.[10] Work continued on the downhill side towards the Hudson, and when the marsh froze in winter, the crews worked to complete the section across the swamps.

The middle section from Utica to Salina (Syracuse) was completed in 1820, and traffic on that section started up immediately. Expansion to the east and west proceeded, and the whole eastern section, 250 miles (400 km) from Brockport to Albany, opened on September 10, 1823 to great fanfare.

The Champlain Canal, a separate but interconnected 64-mile (103 km) north-south route from Watervliet on the Hudson to Lake Champlain, opened on the same date.

In 1824, before the canal was completed, a detailed Pocket Guide for the Tourist and Traveler, Along the Line of the Canals, and the Interior Commerce of the State of New York, was published for the benefit of travelers and land speculators.

After Montezuma Marsh, the next difficulties were crossing Irondequoit Creek and the Genesee River near Rochester. The first ultimately required building the 1,320-foot (400 m) long "Great Embankment" which carried the canal at a height of 76 feet (23 m) above the level of the creek, which was carried through a 245-foot (75 m) culvert underneath.[11] The river was crossed on a stone aqueduct 802 feet (244 m) long and 17 feet (5.2 m) wide, with 11 arches.[12]

After the Genesee, the next obstacle was crossing the Niagara Escarpment, an 80-foot (24 m) wall of hard dolomitic limestone, to rise to the level of Lake Erie. The route followed the channel of a creek that had cut a ravine steeply down the escarpment, with two sets of five locks in a series, soon giving rise to the community of Lockport. The 12-foot (3.7 m) lift-locks had a total lift of 60 feet (18 m), exiting into a deeply cut channel. The final leg had to be cut 30 feet (9.1 m) through another limestone layer, the Onondaga ridge. Much of that section was blasted with black powder, and the inexperience of the crews often led to accidents, and sometimes rocks falling on nearby homes.

Two villages competed to be the terminus: Black Rock, on the Niagara River, and Buffalo, at the eastern tip of Lake Erie. Buffalo expended great energy to widen and deepen Buffalo Creek to make it navigable and to create a harbor at its mouth. Buffalo won over Black Rock, and grew into a large city, eventually encompassing its former competitor.

The entire canal was officially completed on October 26, 1825. The event was marked by a statewide "Grand Celebration," culminating in successive cannon shots along the length of the canal and the Hudson, a 90-minute cannonade from Buffalo to New York City. A flotilla of boats, led by Governor Dewitt Clinton aboard the Seneca Chief, sailed from Buffalo to New York City in ten days. Clinton then ceremonially poured Lake Erie water into New York Harbor to mark the "Wedding of the Waters". On its return trip, the Seneca Chief brought a keg of Atlantic Ocean water back to Buffalo to be poured into Lake Erie by Buffalo's Judge Samuel Wilkeson, who would later become mayor.

The Erie Canal was thus completed in eight years at a cost of $7,143,000.[13] It was acclaimed as an engineering marvel that united the country and helped New York City to become a financial capital.[1]

Route

The canal began on the west side of the Hudson River at Albany, and ran north to Watervliet, where the Champlain Canal branched off. At Cohoes, it climbed the escarpment on the west side of the Hudson River and then turned west along the south shore of the Mohawk River, crossing to the north side at Crescent and again to the south at Rexford. The canal continued west near the south shore of the Mohawk River all the way to Rome, where the Mohawk turns north.[1]

At Rome, the canal continued west parallel to Wood Creek, which flows westward into Oneida Lake, and turned southwest and west cross-country to avoid the lake. From Canastota west, it ran roughly along the north (lower) edge of the Onondaga Escarpment, passing through Syracuse and Rochester. Before reaching Rochester, the canal uses a series of natural ridges to cross the deep valley of Irondequoit Creek. At Lockport the canal turned southwest to rise to the top of the Niagara Escarpment, using the ravine of Eighteen Mile Creek.[1]

The canal continued south-southwest to Pendleton, where it turned west and southwest, mainly using the channel of Tonawanda Creek. From Tonawanda south toward Buffalo, it ran just east of the Niagara River, where it reached its "Western Terminus" at Little Buffalo Creek (later it became the Commercial Slip), which discharged into the Buffalo River just above its confluence with Lake Erie.[1] With Buffalo's re-excavation of Commercial Slip, completed in 2008, the Canal's original terminus is now re-watered and again accessible by boats. With several miles of the Canal inland of this location still lying under 20th-century fill and urban construction, the effective western navigable terminus of the Erie Canal is found at Tonawanda.

The Erie made use of the favorable conditions of New York's unique topography providing that area with the only break in the Appalachians south of the Saint Lawrence River. The Hudson is tidal to Troy, and Albany is west of the Appalachians. It allowed for east-west navigation from the coast to the Great Lakes within US territory.[14] The canal system thus gave New York a competitive advantage, helped New York City develop as an international trade center, and allowed Buffalo to grow from just 200 settlers in 1820 to more than 18,000 people by 1840. The port of New York became essentially the Atlantic home port for all of the Midwest – because of this vital connection and others to follow, such as the railroads, New York would become known as the "Empire State" or "the great Empire State".[1]

Enlargements and improvements

Problems developed but were quickly solved. Leaks developed along the entire length of the canal, but these were sealed using cement that hardened underwater (hydraulic cement). Erosion on the clay bottom proved to be a problem and the speed was limited to 4 mph (6 km/h).

The original design planned for an annual tonnage of 1.5 million tons (1.36 million metric tons), but this was exceeded immediately. An ambitious program to improve the canal began in 1834. During this massive series of construction projects, known as the First Enlargement, the canal was widened to 70 feet (21 m) and deepened to 7 feet (2.1 m). Locks were widened and/or rebuilt in new locations, and many new navigable aqueducts were constructed. The canal was straightened and slightly re-routed in some stretches, resulting in the abandonment of short segments of the original 1825 canal. The First Enlargement was completed in 1862, with further minor enlargements in later decades.

Today, the reconfiguration of the canal created during the First Enlargement is commonly referred to as the Improved Erie Canal or the Old Erie Canal, to distinguish it from the canal's modern-day course. Existing remains of the 1825 canal abandoned during the Enlargement are sometimes referred to today as Clinton's Ditch (which was also the popular nickname for the entire Erie Canal project during its original 1817–1825 construction).

Additional feeder canals soon extended the Erie Canal into a system. These included the Cayuga-Seneca Canal south to the Finger Lakes, the Oswego Canal from Three Rivers north to Lake Ontario at Oswego, and the Champlain Canal from Troy north to Lake Champlain. From 1833 to 1877, the short Crooked Lake Canal connected Keuka Lake and Seneca Lake. The Chemung Canal connected the south end of Seneca Lake to Elmira in 1833, and was an important route for Pennsylvania coal and timber into the canal system. The Chenango Canal in 1836 connected the Erie Canal at Utica to Binghamton and caused a business boom in the Chenango River valley. The Chenango and Chemung canals linked the Erie with the Susquehanna River system. The Black River Canal connected the Black River to the Erie Canal at Rome and remained in operation until the 1920s. The Genesee Valley Canal was run along the Genesee River to connect with the Allegheny River at Olean, but the Allegheny section, which would have connected to the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, was never built. The Genesee Valley Canal was later abandoned and became the route of the Genesee Valley Canal Railroad.

In 1903 the New York State legislature authorized construction of the New York State Barge Canal as the "Improvement of the Erie, the Oswego, the Champlain, and the Cayuga and Seneca Canals".[15]:14 In 1905, construction of the Barge Canal began, which was completed in 1918, at a cost of $96.7 million.[15]:557 Freight traffic reached a total of 5.2 million short tons (4.7 million metric tons) by 1951, before declining in the face of combined rail and truck competition.

Competition

As the canal brought travelers to New York City, it took business away from other ports such as Philadelphia and Baltimore. Those cities and their states started projects to compete with the Erie Canal. In Pennsylvania, the Main Line of Public Works was a combined canal and railroad running west from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh on the Ohio River, opened in 1834. In Maryland, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad ran west to Wheeling, West Virginia, also on the Ohio River, and was completed in 1853.

Other competition was more direct. The Mohawk and Hudson Railroad opened in 1837, providing a bypass to the slowest part of the canal between Albany and Schenectady. Other railroads were soon chartered and built to continue the line west to Buffalo, and in 1842 a continuous line (which later became the New York Central Railroad and its Auburn Road in 1853) was open the whole way to Buffalo. As the railroad served the same general route as the canal, but provided for faster travel, passengers soon switched to it. However, as late as 1852, the canal carried thirteen times more freight tonnage than all the railroads in New York State combined; it continued to compete well with the railroads through 1902, when tolls were abolished.

The New York, West Shore and Buffalo Railway was completed in 1884, as a route running closely parallel to both the canal and the New York Central Railroad. However, it went bankrupt and was acquired the next year by the New York Central.

Impact

The Erie Canal greatly lowered the cost of shipping between the Midwest and the Northeast, bringing much lower food costs to Eastern cities and allowing the East to economically ship machinery and manufactured goods to the Midwest. The canal also made an immense contribution to the wealth and importance of New York City, Buffalo, and New York State. Its impact went much further, increasing trade throughout the nation by opening eastern and overseas markets to Midwestern farm products and by enabling migration to the West.[16][17]

New ethnic Irish communities formed in some towns along its route after completion, as Irish immigrants were a large portion of the construction labor force. Earth extracted from the canal was transported to the New York city area and used as landfill in New York and New Jersey. A plaque honoring the canal's construction is located in Battery Park in southern Manhattan.

Because so many immigrants traveled on the canal, many genealogists have sought copies of canal passenger lists. Apart from the years 1827–1829, canal boat operators were not required to record or report passenger names to the government, which, in this case, was the state of New York. Those 1827–1829 passenger lists survive today in the New York State Archives, and other sources of traveler information are sometimes available.

The Canal also helped bind the still-new nation closer to Britain and Europe. British repeal of the Corn Law resulted in a huge increase in exports of Midwestern wheat to Britain. Trade between the United States and Canada also increased as a result of the Corn Law and a reciprocity (free-trade) agreement signed in 1854; much of this trade flowed along the Erie.

Its success also prompted imitation: a rash of canal-building followed. Also, the many technical hurdles that had to be overcome made heroes of those whose innovations made the canal possible. This led to an increased public esteem for practical education. Chicago, among other Great Lakes cities, recognized the commercial importance of the canal to its economy, and two West Loop streets are named Canal and Clinton (for canal proponent DeWitt Clinton).

Concern that erosion caused by logging in the Adirondacks could silt up the canal contributed to the creation of another New York National Historic Landmark, the Adirondack Park, in 1885.

Many notable authors wrote about the canal, including Herman Melville, Frances Trollope, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mark Twain, Samuel Hopkins Adams and the Marquis de Lafayette, and many tales and songs were written about life on the canal. The popular song "Low Bridge" by Thomas S. Allen was written in 1905 to memorialize the canal's early heyday, when barges were pulled by mules rather than engines.

20th century

In 1918, the Canal was replaced by the larger New York State Barge Canal. This new canal replaced much of the original route, leaving many abandoned sections (most notably between Syracuse and Rome). New digging and flood control technologies allowed engineers to canalize rivers that the original canal had sought to avoid, such as the Mohawk, Seneca, and Clyde rivers, and Oneida Lake. In sections that did not consist of canalized rivers (particularly between Rochester and Buffalo), the original Erie Canal channel was enlarged to 120 feet (37 m) wide and 12 feet (3.7 m) deep. The expansion allowed barges up to 2,000 short tons (1,800 t) to use the Canal. This expensive project was politically unpopular in parts of the state not served by the canal, and failed to save it from becoming obsolete for commercial shipping.

The new alignment began on the Hudson River at the border between Cohoes and Waterford, where it ran northwest with five locks (the so-called "Waterford Flight"), running into the Mohawk River east of Crescent. The Waterford Flight is claimed to be one of the steepest series of locks in the world.[18][1]:19

While the old Canal ran next to the Mohawk all the way to Rome, the new canal ran through the river, which was straightened or widened where necessary.[1]:13 At Ilion, the new canal left the river for good, but continued to run on a new alignment parallel to both the river and the old canal to Rome. From Rome, the new route continued almost due west, merging with Fish Creek just east of its entry into Oneida Lake.

From Oneida Lake, the new canal ran west along the Oneida River, with cutoffs to shorten the route. At Three Rivers the Oneida River turns northwest, and was deepened for the Oswego Canal to Lake Ontario. The new Erie Canal turned south there along the Seneca River, which turns west near Syracuse and continues west to a point in the Montezuma Marsh (43°00′11″N 76°43′52″W / 43.00296°N 76.73115°W). There the Cayuga and Seneca Canal continued south with the Seneca River, and the new Erie Canal again ran parallel to the old canal along the bottom of the Niagara Escarpment, in some places running along the Clyde River, and in some places replacing the old canal. At Pittsford, southeast of Rochester, the canal turned west to run around the south side of Rochester, rather than through downtown. The canal crosses the Genesee River at the Genesee Valley Park (43°07′17″N 77°38′33″W / 43.1215°N 77.6425°W), then rejoins the old path near North Gates.

From there it was again roughly an upgrade to the original canal, running west to Lockport. This reach of 64.2 miles from Henrietta to Lockport is called "the 60‑mile level" since there are no locks and the water level rises only two feet over the entire segment. Diversions from and to adjacent natural streams along the way are used to maintain the canal's level. It runs southwest to Tonawanda, where the new alignment discharges into the Niagara River, which is navigable upstream to the New York Barge Canal's Black Rock Lock and thence to the Canal's original "Western Terminus" at Buffalo's Inner Harbor.

The growth of railroads and highways across the state, and the opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway, caused commercial traffic on the canal to decline dramatically during the second half of the 20th century.

New York State Canal System

In 1992, the New York State Barge Canal was renamed the New York State Canal System (including the Erie, Cayuga-Seneca, Oswego, and Champlain canals) and placed under the newly created New York State Canal Corporation, a subsidiary of the New York State Thruway Authority. The canal system is operated using money generated by Thruway tolls.

21st century

Since the 1990s, the canal system has been used primarily by recreational traffic, although a small but growing amount of cargo traffic still uses it.

Today, the Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor covers 524 miles (843 km) of navigable water from Lake Champlain to the Capital Region and west to Buffalo. The area has a population of 2.7 million: about 75% of Central and Western New York's population lives within 25 miles (40 km) of the Erie Canal.

The Erie Canal is open to small craft and some larger vessels from May through November each year. During winter, water is drained from parts of the canal for maintenance. The Champlain Canal, Lake Champlain, and the Chambly Canal, and Richelieu River in Canada form the Lakes to Locks Passage, making a tourist attraction of the former waterway linking eastern Canada to the Erie Canal. In 2006 recreational boating fees were eliminated to attract more visitors.

Travel on the canal's middle section (particularly in the Mohawk Valley) was severely hampered by flooding in late June and early July 2006. Flood damage to the canal and its facilities was estimated as at least $15 million.

There were some 42 commercial shipments on the canal in 2008, compared to 15 such shipments in 2007 and more than 33,000 shipments in 1855, the canal's peak year. The new growth in commercial traffic is due to the rising cost of diesel fuel. Canal barges can carry a short ton of cargo 514 miles (827 km) on one gallon of diesel fuel, while a gallon allows a train to haul the same amount of cargo 202 miles (325 km) and a truck 59 miles (95 km). Canal barges can carry loads up to 3,000 short tons (2,700 long tons), and are used to transport objects that would be too large for road or rail shipment.[4] Today, the system is served by several commercial towing companies.[19]

Erie Canal Aqueduct crossing the Genesee River in Rochester, New York. Broad Street now runs atop it. A proposed rewatering project of the Erie Canal Aqueduct to connect to a round lock on the Genesee River is under review. This revitalization project will also facilitate boating. |

On the Erie Canal Aqueduct looking north below Broad Street, downtown Rochester The Aqueduct is divided by the concrete support for the Broad Street Bridge above, in the former bed runs the former Rochester Subway |

A commercial tour boat locks through Baldwinsville's Lock 24. |

Old Erie Canal

Sections of the old Erie Canal not used after 1918 are owned by New York State, or have been ceded to or purchased by counties or municipalities. Many stretches of the old canal have been filled in to create roads such as Erie Boulevard in Syracuse and Schenectady, and Broad Street and the Rochester Subway in Rochester. A 36‑mile (58 km) stretch of the old canal from the town of DeWitt, New York, east of Syracuse, to just outside Rome, New York, is preserved as the Old Erie Canal State Historic Park. In 1960 the Schoharie Crossing State Historic Site, a section of the canal in Montgomery County, was one of the first sites recognized as a National Historic Landmark.[20]

Some municipalities have preserved sections as town or county canal parks, or have plans to do so. Camillus Erie Canal Park preserves a 7-mile (11 km) stretch and has restored Nine Mile Creek Aqueduct, built in 1841 as part of the First Enlargement of the canal.[21] In some communities, the old canal has refilled with overgrowth and debris. Proposals have been made to rehydrate the old canal through downtown Rochester or Syracuse as a tourist attraction. In Syracuse, the location of the old canal is represented by a reflecting pool in downtown's Clinton Square and the downtown hosts a canal barge and weigh lock structure, now dry. Buffalo's Commercial Slip is the restored and re-watered segment of the canal which formed its "Western Terminus".

The Erie Canal is a destination for tourists from all over the world. An Erie Canal Cruise company, based in Herkimer, operates from mid-May until mid-October with daily cruises. The cruise goes through the history of the canal and also takes passengers through Lock 18.

In 2004, the administration of New York Governor George Pataki was criticized when officials of New York State Canal Corporation attempted to sell private development rights to large stretches of the Old Erie Canal to a single developer for $30,000, far less than the land was worth on the open market. After an investigation by the Syracuse Post-Standard newspaper, the Pataki administration nullified the deal.

Records of the planning, design, construction, and administration of the Erie Canal are vast and can be found in the New York State Archives. Except for two years (1827–1829), the State of New York did not require canal boat operators to maintain or submit passenger lists.[22]

Parks and museums

Parks and museums related to the old Erie Canal include (listed from East to West):

- Day Peckinpaugh ship; restoration and conversion to a floating museum was planned for completion in 2012 by the New York State Museum

- Watervliet Side Cut Locks, located at Watervliet and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1971[23]

- Enlarged Erie Canal Historic District (Discontiguous), a national historic district located at Cohoes, New York listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004[23]

- Enlarged Double Lock No. 23, Old Erie Canal, Rotterdam

- Schoharie Crossing State Historic Site at Fort Hunter

- Old Erie Canal State Historic Park, 36-mile linear park from Rome to DeWitt

- Erie Canal Village, near Rome

- Canastota Canal Town Museum, Canastota

- Chittenango Landing Canal Boat Museum, near Chittenango

- Erie Canal Museum in downtown Syracuse

- Camillus Erie Canal Park in Camillus

- Jordan Canal Park in Jordan, town of Elbridge

- Enlarged Double Lock No. 33 Old Erie Canal, St. Johnsville

- Erie Canal Lock 52 Complex, a national historic district located at Port Byron and Mentz in Cayuga County; listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1998[23]

- Seneca River Crossing Canals Historic District, a national historic district located at Montezuma and Tyre in Cayuga County; listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005[23]

- Centerport Aqueduct Park near Weedsport; listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2000[23]

- Lock Berlin Park near Clyde

- Macedon Aqueduct Park near Palmyra

- Old Erie Canal Lock 60 Park in Macedon

- Perinton Park in Perinton near Fairport

- Genesee Valley Park near the city of Rochester

- Spencerport Depot & Canal Museum, Spencerport

- Niagara Escarpment "Flight of Five" locks at Lockport

- Erie Canal Discovery Center, 24 Church Street, Lockport (Locks 34 and 35)

- Buffalo's Commercial Slip at the Canal's "Western Terminus"

Erie Canalway Trail

Locks

The following list of locks is provided for the current canal, from east to west. There are a total of 34 locks on the Erie Canal.

All locks on the New York State Canal System are single-chamber; the dimensions are 328 feet (100 m) long and 45 feet (13.7 m) wide with a minimum 12-foot (3.7 m) depth of water over the miter sills at the upstream gates upon lift. They can accommodate a vessel up to 300 feet (91 m) long and 43.5 feet (13.3 m) wide.[24][25][26] Overall sidewall height will vary by lock, ranging between 28 feet (8.5 m) and 61 feet (18.6 m) depending on the lift and navigable stages. Lock E17 at Little Falls has the tallest sidewall height at 80 feet (24.4 m).[27]

Distance is based on position markers from an interactive canal map provided online by the New York State Canal Corporation and may not exactly match specifications on signs posted along the canal. Mean surface elevations are comprised from a combination of older canal profiles and history books as well as specifications on signs posted along the canal.[24][28][29] The margin of error should normally be within 6 inches (15.2 cm).

The famous Waterford Flight of Locks are on the Erie. Locks E2, E3, E4, E5, and E6 lift boats 169 feet in 2 miles.

All surface elevations are approximate.

| Lock # | Location | Elevation

(upstream/west) |

Elevation

(downstream/east) |

Lift or Drop | Distance to Next Lock

(upstream/west) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Troy Lock * | Troy | 15.3 ft (4.7 m) | 1.3 ft (0.40 m) | 14.0 ft (4.3 m) | E2, 2.66 mi (4.28 km) |

| E2 | Waterford | 48.9 ft (14.9 m) | 15.3 ft (4.7 m) | 33.6 ft (10.2 m) | E3, 0.46 mi (0.74 km) |

| E3 | Waterford | 83.5 ft (25.5 m) | 48.9 ft (14.9 m) | 34.6 ft (10.5 m) | E4, 0.51 mi (0.82 km) |

| E4 | Waterford | 118.1 ft (36.0 m) | 83.5 ft (25.5 m) | 34.6 ft (10.5 m) | E5, 0.27 mi (0.43 km) |

| E5 | Waterford | 151.4 ft (46.1 m) | 118.1 ft (36.0 m) | 33.3 ft (10.1 m) | E6, 0.28 mi (0.45 km) |

| E6 | Crescent | 184.4 ft (56.2 m) | 151.4 ft (46.1 m) | 33.0 ft (10.1 m) | E7, 10.92 mi (17.57 km) |

| E7 | Vischer Ferry | 211.4 ft (64.4 m) | 184.4 ft (56.2 m) | 27.0 ft (8.2 m) | E8, 10.97 mi (17.65 km) |

| E8 | Scotia | 225.4 ft (68.7 m) | 211.4 ft (64.4 m) | 14.0 ft (4.3 m) | E9, 5.03 mi (8.10 km) |

| E9 | Rotterdam | 240.4 ft (73.3 m) | 225.4 ft (68.7 m) | 15.0 ft (4.6 m) | E10, 5.95 mi (9.58 km) |

| E10 | Cranesville | 255.4 ft (77.8 m) | 240.4 ft (73.3 m) | 15.0 ft (4.6 m) | E11, 4.27 mi (6.87 km) |

| E11 | Amsterdam | 267.4 ft (81.5 m) | 255.4 ft (77.8 m) | 12.0 ft (3.7 m) | E12, 4.23 mi (6.81 km) |

| E12 | Tribes Hill | 278.4 ft (84.9 m) | 267.4 ft (81.5 m) | 11.0 ft (3.4 m) | E13, 9.60 mi (15.45 km) |

| E13 | Yosts | 286.4 ft (87.3 m) | 278.4 ft (84.9 m) | 8.0 ft (2.4 m) | E14, 7.83 mi (12.60 km) |

| E14 | Canajoharie | 294.4 ft (89.7 m) | 286.4 ft (87.3 m) | 8.0 ft (2.4 m) | E15, 3.35 mi (5.39 km) |

| E15 | Fort Plain | 302.4 ft (92.2 m) | 294.4 ft (89.7 m) | 8.0 ft (2.4 m) | E16, 6.72 mi (10.81 km) |

| E16 | St. Johnsville | 322.9 ft (98.4 m) | 302.4 ft (92.2 m) | 20.5 ft (6.2 m) | E17, 7.97 mi (12.83 km) |

| E17 | Little Falls | 363.4 ft (110.8 m) | 322.9 ft (98.4 m) | 40.5 ft (12.3 m) | E18, 4.20 mi (6.76 km) |

| E18 | Jacksonburg | 383.4 ft (116.9 m) | 363.4 ft (110.8 m) | 20.0 ft (6.1 m) | E19, 11.85 mi (19.07 km) |

| E19 | Frankfort | 404.4 ft (123.3 m) | 383.4 ft (116.9 m) | 21.0 ft (6.4 m) | E20, 10.28 mi (16.54 km) |

| E20 | Whitesboro | 420.4 ft (128.1 m) | 404.4 ft (123.3 m) | 16.0 ft (4.9 m) | E21, 18.10 mi (29.13 km) |

| E21 | New London | 395.4 ft (120.5 m) | 420.4 ft (128.1 m) | −25.0 ft (−7.6 m) | E22, 1.32 mi (2.12 km) |

| E22 | New London | 370.1 ft (112.8 m) | 395.4 ft (120.5 m) | −25.3 ft (−7.7 m) | E23, 28.91 mi (46.53 km) |

| E23 | Brewerton | 363.0 ft (110.6 m) | 370.1 ft (112.8 m) | −7.1 ft (−2.2 m) | E24, 18.77 mi (30.21 km) |

| E24 | Baldwinsville | 374.0 ft (114.0 m) | 363.0 ft (110.6 m) | 11.0 ft (3.4 m) | E25, 30.69 mi (49.39 km) |

| E25 | Mays Point | 380.0 ft (115.8 m) | 374.0 ft (114.0 m) | 6.0 ft (1.8 m) | E26, 5.83 mi (9.38 km) |

| E26 | Clyde | 386.0 ft (117.7 m) | 380.0 ft (115.8 m) | 6.0 ft (1.8 m) | E27, 12.05 mi (19.39 km) |

| E27 | Lyons | 398.5 ft (121.5 m) | 386.0 ft (117.7 m) | 12.5 ft (3.8 m) | E28A, 1.28 mi (2.06 km) |

| E28A | Lyons | 418.0 ft (127.4 m) | 398.5 ft (121.5 m) | 19.5 ft (5.9 m) | E28B, 3.98 mi (6.41 km) |

| E28B | Newark | 430.0 ft (131.1 m) | 418.0 ft (127.4 m) | 12.0 ft (3.7 m) | E29, 9.79 mi (15.76 km) |

| E29 | Palmyra | 446.0 ft (135.9 m) | 430.0 ft (131.1 m) | 16.0 ft (4.9 m) | E30, 2.98 mi (4.80 km) |

| E30 | Macedon | 462.4 ft (140.9 m) | 446.0 ft (135.9 m) | 16.4 ft (5.0 m) | E32, 16.12 mi (25.94 km) |

| E32 | Pittsford | 487.5 ft (148.6 m) | 462.4 ft (140.9 m) | 25.1 ft (7.7 m) | E33, 1.26 mi (2.03 km) |

| E33 | Rochester | 512.9 ft (156.3 m) | 487.5 ft (148.6 m) | 25.4 ft (7.7 m) | E34/35, 64.28 mi (103.45 km) |

| E34 | Lockport | 539.5 ft (164.4 m) | 514.9 ft (156.9 m) | 24.6 ft (7.5 m) | E35, adjacent to Lock E34. |

| E35 | Lockport | 564.0 ft (171.9 m) | 539.5 ft (164.4 m) | 24.5 ft (7.5 m) | Black Rock Lock in Niagara River, 26.39 mi (42.47 km) |

| Black Rock Lock * | Buffalo | 570.6 ft (173.9 m) | 565.6 ft (172.4 m) | 5.0 ft (1.5 m) | Commercial Slip at Buffalo River, 3.89 mi (6.26 km) |

* Denotes Federal managed locks.

There is roughly a 2-foot (0.6 m) natural rise between locks E33 and E34 as well as a 1.5-foot (0.5 m) natural rise between Lock E35 and the Niagara River.[26]

- Note: There is no Lock E1 or Lock E31 on the Erie Canal. The place of "Lock E1" on the passage from the lower Hudson River to Lake Erie is taken by the Troy Federal Lock, located just north of Troy, New York, and is not part of the Erie Canal System proper. It is operated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers.[24] The Erie Canal officially begins at the confluence of the Hudson and Mohawk rivers at Waterford, New York.

- Note: The Black Rock Lock is in the New York State Barge Canal, and allows passage beside the Niagara River to the Erie Canal's "Western Terminus" at the Commercial Slip. Upstream and downstream water levels, as well as Black Rock Lock's lift, vary with the naturally fluctuating levels of Lake Erie and the Niagara River. Although a portion of the Erie Canal through Buffalo has been filled in, travel by water is still possible, from the Commercial Slip, through Buffalo's Inner Harbor and the Black Rock Lock, to Tonawanda, New York, Lockport, and eastward to Albany. The lock is operated by the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

- Note: The Waterford Flight series of locks (comprising Locks E2 through E6) is one of the steepest in the world.[1]:19[18]

Oneida Lake lies between locks E22 and E23, and has a mean surface elevation of 370 feet (112.8 m). Lake Erie has a mean surface elevation of 571 feet (174.1 m).

See also

- Alfred Barrett

- "Low Bridge", song written by Thomas S. Allen, also known as "The Erie Canal Song"

- Illinois and Michigan Canal, connecting Lake Michigan with the Mississippi River

- Ohio and Erie Canal, connecting Lake Erie with the Ohio River, and thus the Mississippi River

- List of canals in New York

- List of canals in the United States

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Finch, Roy G. (1925). "The Story of the New York State Canals" (PDF). New York State Engineer and Surveyor (republished by New York State Canal Corporation). Retrieved 2012-09-25.

- ↑ "Works of Man", Ronald W. Clark, ISBN 0-670-80483-5 (1985) 352 pages, Viking Penguin, Inc, NYC, NY,

quotation page 87: "There was little experience moving bulk loads by carts, while a packhorse would [sic, meaning 'could' or 'can only'] carry only an eighth of a ton. On a soft road a horse might be able to draw 5/8ths of a ton. But if the load were carried by a barge on a waterway, then up to 30 tons could be drawn by the same horse." - 1 2 "Erie Canalway National Heritage Corridor". Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- 1 2 Christopher Maag (November 2, 2008). "Hints of Comeback for Nation's First Superhighway". New York Times.

- ↑ "Railroad Travel Rates, 1800–1930".

- ↑ Joel Achenbach, "America's River; From Washington and Jefferson to the Army Corps of Engineers, everyone had grandiose plans to tame the Potomac. Fortunately for us, they all failed". The Washington Post, May 5, 2002; p. W.12.

- 1 2 Wedding of the Waters: The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation, Peter L. Bernstein

- ↑ Hunter, Louis C.; Bryant, Lynwood (1991). A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1730–1930, Vol. 3: The Transmission of Power. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-08198-9.

- ↑ Gerard Koeppel (2009). Bond of Union: Building the Erie Canal and the American Empire. Da Capo Press,. pp. 212–13.

- ↑ Andrew Kitzmann (2009). Postcard History Series:Erie Canal. Arcadia Publishing. p. 71.

- ↑ Farley, Doug (September 18, 2007). "ERIE CANAL DISCOVERY: The great embankment". Lockport Union-Sun & Journal. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ↑ "The Genesee River Aqueduct". The Erie Canal. Monroe County Library System. Retrieved May 12, 2015.

- ↑ Ransom, Roger (May 1964). "Canals and Development: A Discussion of the Issues". American Economic Review 54 (3): 375.

- ↑ http://www.history.rochester.edu/canal/bib/whitford/1906/Chap01.html

- 1 2 Whiteford, Noble E. (1922). History of the Barge Canal of New York State. J. B. Lyon Company. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

- ↑ Taylor, George Rogers. The Transportation Revolution, 1815–1860. ISBN 978-0-87332-101-3.

- ↑ North, Douglas C. (1966). The Economic Growth of the United States 1790–1860. New York, London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-00346-8.

- 1 2 "Dedication of the Flight of Five Locks as a Civil Engineering Landmark (9/9/2012)". ASCE Rennselaer. American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), RPI Chapter. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ↑ Commercial Shipping on the New York State Canal System Archived March 5, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ National Park Service, National Historic Landmarks Survey, New York, retrieved May 30, 2007. Archived July 7, 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Camillus Erie Canal Park, Nine Mile Creek Aqueduct, retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ↑ New York State Archives. Research at libraries, churches, and town halls of the ultimate destinations of canal travelers may provide passenger information. "Guide to Canal Records." www.archives.nysed.gov Archived January 1, 1970 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 5 Staff (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 New York State Canal Corporation - Canal Map, New York State Canals, Retrieved Jan. 26, 2015.

- ↑ New York State Canal Corporation - Frequently Asked Questions, Retrieved Jan. 26, 2015.

- 1 2 The Erie Canal - Locks, Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ↑ The Erie Canal, History of the Barge Canal of New York State by Noble E. Whitford, 1921, Chapter 23, Retrieved Jan. 28, 2015.

- ↑ Wilfred H. Schoff, The New York State Barge Canal, 1915, American Geographical Society, Vol. 47, No. 7, page 498, Retrieved Jan. 26, 2015.

- ↑ The Erie Canal - Canal Profiles, Retrieved Jan. 6, 2015.

Further reading

- Bernstein, Peter L. Wedding of the Waters: The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation, (W.W. Norton, 2005), ISBN 0-393-05233-8.

- Finch, Roy G. (1925). The Story of the New York State Canals: Historical and Commercial Information (PDF). New York State Canal Corporation. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- Koeppel, Gerard. Bond of Union: Building the Erie Canal and the American Empire, Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press, 2009, ISBN 0-306-81827-2 online review

- McGreevy, Patrick. Stairway to Empire: Lockport, the Erie Canal, and the Shaping of America ( Albany: SUNY Press, 2009) ISBN 978-1-4384-2527-6 online review

- Panagopoulos, Janie Lynn. "Erie Trail West", River Road Publications 1995, ISBN 0-938682-35-0

- Papp, John P. The Erie Canal Albany to Buffalo. Schenectady, New York: Historical Publications (1977).

- Shaw, Ronald E. Erie water west: a history of the Erie Canal, 1792–1854 (1990) online edition

- Sheriff, Carol. The Artificial River: The Erie Canal and the Paradox of Progress, 1817–1862, by New York : Hill and Wang, 1996, ISBN 0-8090-2753-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Erie Canal. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Erie Canal. |

- Information and Boater's Guide to the Erie Canal

- Canalway Trail Information

- Historical information (with photos) of the Erie Canal

- New York State Canal Corporation Site

- The Opening of the Erie Canal - An Online Exhibition by CUNY

- The Canal Society of New York State

- Digging Clinton's Ditch: The Impact of the Erie Canal on America 1807–1860 Multimedia

- A Glimpse at Clinton's Ditch, 1819–1820 by Richard F. Palmer

- Guide to Canal Records in the New York State Archives

- The Erie Canal Mapping Project

- New York Heritage - Working on the Erie Canal

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NY-231, "Erie Canal Viaduct, Moyer Creek Crossing"

- HABS No. NY-6040, "Erie Canal Locks"

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NY-6, "Erie Canal (Enlarged), Schoharie Creek Aqueduct"

- HAER No. NY-11, "Erie Canal (Enlarged), Lock Number 18"

- HAER No. NY-12, "Erie Canal (Enlarged), Upper Mohawk River Aqueduct"

- HAER No. NY-16, "Erie Canal, Yankee Hill Lock Number 28"

- HAER No. NY-17, "Erie Canal (Enlarged), Empire Lock Number 29"

- HAER No. NY-152, "Erie Canal (Enlarged), Oothout Culvert & Waste Weir"

- HAER No. NY-157, "Eagle's Nest Creek Culvert"

- HAER No. NY-337, "Erie Canal (Original), Locks 37 & 38"

- HAER No. NY-545, "Erie Canal (Original), Lock Number 20"

|