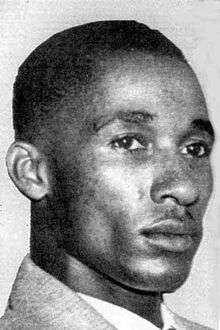

Lloyd L. Gaines

| Lloyd L. Gaines | |

|---|---|

Lloyd Gaines | |

| Born |

Lloyd Lionel Gaines 1911 Water Valley, Mississippi, US |

| Disappeared |

March 19, 1939 Chicago, Illinois, US |

| Status | Missing for 76 years, 10 months and 30 days |

| Ethnicity | African American |

| Education | B.A., history; M.A., economics |

| Alma mater | Lincoln University |

| Occupation | Student, odd jobs |

| Known for |

Successful legal challenge to racial discrimination; inexplicable disappearance |

Lloyd Lionel Gaines (1911, Water Valley, Mississippi – disappeared March 19, 1939, Chicago) was the plaintiff in Gaines v. Canada (1938), one of the most important court cases in the U.S. civil rights movement in the 1930s. After being denied admission to the University of Missouri School of Law because he was African American, and refusing the university's offer to pay for him to attend another neighboring state's law school with no racial restriction, he filed suit. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ruled in his favor, holding that the separate but equal doctrine required that Missouri either admit him or set up a separate law school for African American students.

The Missouri General Assembly chose the latter option, converting a former cosmetology school in St. Louis to the Lincoln University School of Law and other mostly African-American students were admitted to it. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which had supported Gaines' suit, planned to file another suit challenging the adequacy of the new law school. While he waited for classes to begin, Gaines traveled between St. Louis, Kansas City and Chicago looking for work, doing odd jobs and giving speeches before local NAACP chapters. One night in Chicago he left the fraternity house where he was staying to buy stamps and never returned.

His disappearance was not noted immediately, since he would frequently travel on his own for long periods of time without informing anyone. Only in the autumn of that year, when the NAACP's lawyers were unable to locate him to take depositions for a rehearing in state court, did a serious search begin. It failed, and the suit was dismissed. While most of his family believed at the time that he had been murdered in retaliation for his legal victory, there has been some speculation that he had tired of his role in the civil rights movement and simply went elsewhere, either New York or Mexico City, to start a new life. In 2007 the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agreed to look into the case, among many other unsolved missing persons cases related to the civil rights era.

Despite his unknown fate, Gaines has been honored by the University of Missouri School of Law and the state. The Black Culture Center at the University of Missouri and a law scholarship at the law school are named for him and another African American student initially denied admission, and in 2006 he was granted an honorary law degree. The state bar association followed with a posthumous law license. A portrait of Gaines hangs in the University of Missouri law school building.

Early life

Born in 1911 in Water Valley, Mississippi, Gaines moved with his mother and siblings to St. Louis in 1926 after the death of his father, settling in the city's Central West End neighborhood. He did well academically, and was a valedictorian at Vashon High School. After winning a $250 ($3,000 in modern dollars)[1] scholarship[2] in an essay contest, he went to college and graduated with honors from Lincoln University in Jefferson City, the state's undergraduate institution for African Americans, with a bachelor's degree in history. He made up the difference between the scholarship and the college's tuition by selling magazines on the street.[3] He was president of the senior class and a brother in the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.[4]

Lawsuit

In 1936, he applied for admission to the law school at the University of Missouri, encouraged by Lorenzo Greene, a Lincoln University professor at the time and veteran civil rights activist. Accounts vary as to whether Gaines did this purely on his own initiative or was encouraged by the NAACP simply to have a plaintiff, without any real interest of his own in attending law school.[5] When St. Louis lawyer Sidney Redmond, one of the three dozen African Americans then admitted to the Missouri bar, informed Charles Hamilton Houston, who was leading the NAACP's legal effort against the segregationist Jim Crow laws, that Gaines was willing to be a plaintiff, Houston at first asked him if he could find someone else. Houston later yielded when it was apparent Gaines was the only available plaintiff, but never explained what his initial objections might have been.[6]

The law school's registrar, Sy Woodson Canada, had denied Gaines' admission on racial grounds although he was otherwise qualified for admission to the law school. The official policy of the State of Missouri was to pay the "out of state" expenses for education of African Americans who wished to study law until such time as demand was sufficient to build a separate law school within the State of Missouri for them. Gaines and his lawyers argued that lawyers educated out of state lost the benefit of courses that were specific to Missouri law, and the connections and firsthand experience of the state's courts an in-state legal education would offer.[7]

Gaines and his lawyers were not hoping to overturn the "separate but equal" standard set out by the Court's 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision allowing legal racial segregation, but rather to subtly undermine it by holding states that did segregate along racial lines to the "equal" part of the doctrine. They targeted graduate and professional public institutions of higher learning, which unlike most other segregated facilities were few in number and under centralized state control. Once segregationist states realized they had a choice between expensive duplication of such institutions for a small group of African Americans and integration of their existing facilities, they would choose the latter and voluntarily integrate.[8] Houston also believed that since such schools served small portions of the population, attempts to integrate them would arouse less public opposition than efforts to integrate elementary and secondary schools would. Lastly, judges had themselves been educated in them and could better understand the impact of inequalities on students.[5]

They were encouraged by a 1936 case, University of Maryland v. Murray, in which Houston and Thurgood Marshall had persuaded the Maryland Court of Appeals, that state's highest court, that the University of Maryland could not meet its constitutional burden of equal treatment by offering to reimburse him for tuition out of state instead of allowing him to attend the university, which as an African American he was barred by the university's administration from doing.[9] In Missouri Gaines was likely as well to be offered reimbursement for his out-of-state tuition; however, the racial bar to attendance took the form of a state law instead of an administrative regulation. They hoped to get the Supreme Court to hear the case and establish a precedent.[10]

Houston, Redmond and Gaines left St. Louis before dawn one summer day that year to drive to Columbia for the trial at Boone County courthouse. They arrived as the courthouse was beginning to open for the morning. Due to that summer's severe drought, many of the white farmers in the surrounding communities were there, waiting to make applications for relief. Some went into the courtroom to take in the unusual sight of African American lawyers arguing a case.[11]

They were joined by a hundred current University of Missouri law students, reporters, and a few local African Americans. Two recent lynchings had discouraged most of the local black community from attending despite efforts to the contrary by the local NAACP chapters. They sat among the whites since none of the courtroom facilities were segregated. Even the lawyers for both sides shared a table, and shook hands before the case.[11]

By the time trial was to begin, the heat outside had already exceeded 100 °F (38 °C). The crowds and poor ventilation made it even hotter in the courtroom, and Judge W.M. Dinwiddie suggested that he and the lawyers conduct proceedings with their jackets off. Houston claimed Gaines's exclusion from the law school solely on racial grounds violated his constitutional rights. For the state, William Hogsett conceded that Gaines was an excellent and qualified student with a right to a legal education, as long as it was somewhere other than the law school since it was public policy of the state, codified in the constitution and laws enacted by its legislature elected by the people, that African American students not be allowed to attend Missouri law school.[11]

Gaines testified on his own behalf, and various state and university officials for their side. They claimed that admitting African Americans, the only applicants specifically barred regardless of other qualifications, would be "an unhappy thing" for both them and other students. William Masterson, dean of the University of Missouri School of Law, claimed not to know details of the admissions process or the school's budget on cross-examination.[11]

Hogsett presented his case for the audience, some of whom nodded in sympathy with his arguments, while Houston concentrated on getting facts in the record for the appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, the only venue where he expected and wanted to prevail. He never seriously expected to win at trial, and indeed two weeks later Dinwiddie decided the case for the state. The judge did not write an opinion explaining his holding,[11] and Gaines appealed to the Missouri Supreme Court.[5]

The state's highest court heard the arguments near the end of the year. While normally it sat in two divisions, the case was considered so important that all seven justices were present. Two months later, it upheld Judge Dinwiddie.[12] Justice William Francis Frank reiterated the court's earlier holdings for segregation, that it was to the advantage of blacks as well as whites. In Gaines' case, he held that the separate but equal standard was satisfied by the availability of an out-of-state legal education at state expense. "Equality is not identity of privileges," he wrote.[5]

Houston and Redmond successfully petitioned to the United States Supreme Court for certiorari. Now known as Gaines v. Canada, the case was argued on November 9, 1938. Houston said the state's offer to pay for Gaines to attend law school out of state could not guarantee him a legal education equal to that offered white students.[7]

A month later a 6-2[note 1] majority ordered the State of Missouri either to admit Gaines to the University of Missouri School of Law or to provide another school of equal stature within the state borders.[7] Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote for the majority:

The basic consideration is not as to what sort of opportunities other States provide, or whether they are as good as those in Missouri, but as to what opportunities Missouri itself furnishes to white students and denies to negroes solely upon the ground of color. The admissibility of laws separating the races in the enjoyment of privileges afforded by the State rests wholly upon the equality of the privileges which the laws give to the separated groups within the State. The question here is not of a duty of the State to supply legal training, or of the quality of the training which it does supply, but of its duty when it provides such training to furnish it to the residents of the State upon the basis of an equality of right. By the operation of the laws of Missouri a privilege has been created for white law students which is denied to negroes by reason of their race. The white resident is afforded legal education within the State; the negro resident having the same qualifications is refused it there and must go outside the State to obtain it. That is a denial of the equality of legal right to the enjoyment of the privilege which the State has set up, and the provision for the payment of tuition fees in another State does not remove the discrimination.[13]

The case articulated an important rule of law in the sequence of NAACP cases leading to the eventual desegregation order: that any academic program that a state provided to whites had to have an equivalent available to blacks. The Gaines holding helped lay the foundation for the landmark 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, which ordered all public schools desegregated and overturned Plessy by holding that separate facilities were inherently unequal.[2][4]

Since the Supreme Court had ordered the Missouri Supreme Court to rehear the case in light of its ruling, Gaines' legal battle was not over. Historian Gary Lavergne describes Gaines during this period as "high-maintenance". He sought out media attention, then complained about how stressful it was being the center of attention. Heman Marion Sweatt, later the plaintiff in another desegregation case heard by the Supreme Court, worked with Gaines at the University of Michigan, where the NAACP had paid for him to attend graduate school in the meantime, and reportedly found him "rather arrogant."[10]

After working as a clerk for the Works Progress Administration in Michigan and completing a master's degree in economics, Gaines returned to Missouri in anticipation of the proceedings there, set to begin in August. The Missouri legislature hastily passed a bill appropriating $275,000 ($4.68 million in modern dollars[1]) to convert an old beauty school in St. Louis into the new Lincoln University School of Law, in the hope that would satisfy the court. The NAACP planned to challenge the establishment of the new law school as still inadequate compared to the resources of the existing University of Missouri School of Law. Gaines, who would still need to pay his law school tuition as well as his daily living expenses, looked for work in the meantime. Between the continuing Depression and segregation, he had to settle for work at a gas station. He gave speeches to local NAACP chapters and church groups for donations, telling them "I am ready, willing and able to enroll in the law department at the University of Missouri in September, and I have the fullest intention of doing so," but still had to borrow money from his brother George for everyday expenses.[3]

He quit the job at the gas station when he discovered the owner was purposely mislabeling low-grade fuel as high-grade, fearing he might be caught up in the legal consequences should the fraud be discovered. After taking a train across the state to Kansas City to give a speech to the local NAACP chapter and look, unsuccessfully, for work, he boarded another train for Chicago. There he reunited with the Page family, friends and neighbors from his youth in the Central West End, and stayed at a local YMCA.[3]

Disappearance

Over the next several weeks he looked for work and visited with the Pages. While he maintained at public appearances during this time that he was determined to continue his court case till its end and attend the University of Missouri School of Law, in private he was becoming increasingly ambivalent. His mother said he had decided not to go, as they both believed it was "too dangerous". Nancy Page later recalled asking him directly about this. "His answer wasn't straightforward, and if I remember correctly, he said something like this: 'If I don't go, I will have at least made it possible for some other boy or girl to go.'"[3]

In his last letter to his mother, dated March 3, he expressed similar sentiments:

As for my publicity relative to the university case, I have found that my race still likes to applaud, shake hands, pat me on the back and say how great and noble is the idea: how historical and socially important the case but — and it ends ... Off and out of the confines of the publicity columns, I am just a man — not one who has fought and sacrificed to make the case possible: one who is still fighting and sacrificing — almost the 'supreme sacrifice' to see that it is a complete and lasting success for thirteen million Negroes — no! — just another man. Sometimes I wish I were just a plain, ordinary man whose name no one recognized.

He had begun the letter by telling her that he had come to Chicago "hoping to find it possible to make my own way" and ended it "Should I forget to write for a time, don't worry about it. I can look after myself OK".[3]

He also wrote that his accommodations at the Y were paid through March 7, and if he stayed in Chicago after that he would have to make "other arrangements". After that, brothers at an Alpha Phi Alpha house took him in. He continued to have dinner at the Pages'.[3]

Nancy Page said he told her he had taken a job at a department store. A reporter later found that although he had been hired, he had never reported for what would have been his first day of work. In the last days she had contact with him, Page said he seemed "to be running away from something." Gaines family members and descendants believe he and possibly the family as a whole had received death threats, and given their background in rural Mississippi would have been too fearful to report them to the police.[3]

Gaines' financial needs continued. The Alpha Phi Alpha brothers took up a collection for him. He promised the Pages that he would repay their generosity by taking them out to dinner on the night of March 19, but he never did. Earlier that evening, he told the house attendant he was going out on a cold, wet evening to buy some stamps. He never returned, and no one ever reported seeing him again. His ultimate fate remains unknown.[3]

Aftermath

Gaines left behind a duffel bag filled with dirty clothing at the fraternity house when he disappeared. Since he had had a history of leaving for days at a time with little or no notice to his friends and family, and often kept to himself, his absence seemed unremarkable at first. No report was made to the police in either Chicago or St. Louis.[3]

His disappearance finally became an issue several months later. In August, Houston and Sidney Redmond went looking for him as they began to argue his case at the Missouri Supreme Court's rehearing. They could not locate him, and Redmond recalled that the Gaines family was neither concerned nor very helpful in trying to do so. The Lincoln University School of Law in St. Louis opened in late September to pickets denouncing it as a segregationist sham.[14] While 30 students who had been admitted since it was created showed up, Gaines was not among them. Since only Gaines had been denied admission to the University of Missouri School of Law, only he had standing to pursue the case before the Supreme Court of Missouri, and the case could not proceed without him.[3]

Near the end of the year the NAACP began a frantic effort to find him. There were rumors that he had been killed or committed suicide, along with rumors that he had been paid off to disappear and was either living in Mexico City or teaching school in New York.[6] The story received widespread media attention, and his picture was published in newspapers across the country with a plea for anyone with information to contact the NAACP. No credible leads were received. In his 1948 memoirs, NAACP president Walter White said, "He has been variously reported in Mexico, apparently supplied with ample funds, and in other parts of North America."[15]

Gary Lavergne notes that Houston, Marshall and Redmond never publicly called for an investigation of the disappearance or stated that they believed Gaines had met with foul play. Since extrajudicial abductions and murders of African Americans who challenged segregation were not unheard of at the time, and the three lawyers frequently spoke out and demanded investigations when they believed they had occurred, he thinks that they had no such evidence and believed that the erratic Gaines, whom they knew to have grown resentful of the NAACP and his role in the lawsuit, had purposely dropped out of sight.[10] Fifty years later, near the end of his own career as a Supreme Court justice, Marshall recalled the case in terms that suggest this assessment: "The sonofabitch just never contacted us again."[16]

In January 1940, the state of Missouri moved to dismiss the case due to the absence of the plaintiff. Houston and Redmond did not oppose the motion, and it was granted.[4]

Investigations

No law enforcement agency of the era formally investigated Gaines' disappearance. It had not been reported to any of them, and many African Americans distrusted the police. J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), who took a very suspicious view of the civil rights movement, wrote in an internal memo in 1940 that he did not believe the case fell under the FBI's jurisdiction.[2]

With the onset of World War II, other concerns displaced the Gaines case for most of the 1940s. The only other official record relating to the case released by the FBI was a 1970 letter from Hoover to an unidentified member of the public, thanking them for their interest in the case but reiterating his position from 30 years earlier that he did not believe the FBI had any jurisdiction to investigate.[3] Two media outlets looked into the case a half-century apart, Ebony in the 1950s and The Riverfront Times in the 2000s.

Ebony

Ebony reporter Edward T. Clayton revisited Gaines and his disappearance in 1951. It has been described as the most thorough investigation of the case. Clayton retraced Gaines' movements in the months between the Supreme Court ruling and his trip to Chicago. Many who knew Gaines were still alive, such as his family in St. Louis and fraternity brothers in Chicago, and he interviewed them.[3]

He found little new information, but was able to draw a fuller portrait of Gaines that revealed the young man's disillusionment with his activist path. Callie Gaines, bedridden in her attic, shared her last conversation with him in which both of them realized that he wouldn't actually be following through and enrolling in the University of Missouri School of Law. She said that he had sent her a final postcard saying, "Goodbye. If you don't hear from me anymore you know I'll be all right." She had heard all the rumors about him turning up in Mexico or New York. "But nobody knows any more than we do."[3] One of his sisters believed he was still alive.[17] The family has never sought to have him declared legally dead.[3]

Gaines' brother George, who had kept loaning Lloyd spending money at that time, said that at the time of his disappearance Lloyd had owed him $500. He was particularly bitter about the NAACP for, in his opinion, exploiting Lloyd. "That organization—the N-A-A-C-P or whatever it was—had him going around here making speeches," Gaines told Clayton, "but when he got ready to go to Kansas City, I had to let him have $10 so he could get himself a white shirt." Sidney Redmond agreed that the Gaines family "doesn't seem too much concerned—and never was as I recall" about finding him due to their resentment of the civil rights' organization's role in pushing Lloyd Gaines into the public eye without adequately providing for or protecting him.[3]

George Gaines did, however, provide Clayton with Gaines' letters home, including the last one, almost two weeks before he disappeared. In it, Gaines again laments the insufficient support he received from his fellow African Americans and wishes he were just a regular, unknown person again. It, like the postcard, concludes with a suggestion that he may be out of touch for a while.[3] All of them have since been digitized and are currently online at the University of Missouri's digital archives.

In Chicago, Clayton talked to the Alpha Phi Alpha brothers among whom Gaines had spent his last known days and the Pages, his family friends from St. Louis. The former could offer little beyond pinning down the precise date of his disappearance and the duffel bag of dirty laundry he left behind.[3] Two who claimed Gaines had sent them postcards from Mexico were unable to corroborate their accounts with the actual postcards.[17]

The Pages shared the details of Gaines' increasingly anxious state of mind in March 1939. Nancy Page did not inquire closely, out of respect for his privacy, but could tell something was bothering him. She reported a conversation with Gaines in which he was at best ambivalent about continuing the legal case and attending the University of Missouri School of Law. From her Clayton found out about the job Gaines had accepted, and found through his own research that Gaines had never actually started work there.[3]

The Riverfront Times

St Louis' alternative weekly newspaper, The Riverfront Times revisited the case in 2007, well over 60 years after his disappearance. By that time Gaines had received honors (some described as posthumous) and the FBI had accepted the case as the oldest of nearly one hundred civil-rights era disappearances referred to it by the NAACP. His immediate family and all others who had worked or socialized with him during that time were dead. Reporter Chad Garrison spoke with George Gaines, a nephew of Lloyd's who was one of only two surviving family members who had been alive when Lloyd disappeared, although he had only been an infant at the time, and other, younger descendants.[3]

George Gaines said his family had rarely spoken of Lloyd during his childhood in the 1940s, but when they did it was usually in highly positive terms. "Lloyd was always held in high regard as a person who set a positive example and stood up for what was right", he recalled. He had assumed that his uncle had died, and only when he read the Ebony article did he learn that Lloyd's true fate was unknown.[3]

While Garrison mostly reiterated Clayton's reporting, finding no new facts about the disappearance itself or Gaines' time in Chicago, he found more direct evidence that Gaines might indeed have fled to Mexico and lived out his life there. Sid Reedy, a University City librarian who had been an Alpha Phi Alpha brother at Lincoln University as well, told Garrison that after becoming fascinated by the case in the late 1970s, he had sought out Lorenzo Greene, Gaines' mentor at Lincoln University and an esteemed civil rights activist and intellectual. Greene told Reedy that while on a visit to Mexico City in the late 1940s he had made contact with Lloyd Gaines.[3]

Greene, who died in 1988, claimed to have spoken on the telephone with Gaines, whose voice he recognized instantly, several times. The two made plans to have dinner together, but Gaines did not show up. Greene told Reedy that Gaines had indeed "grown tired of the fight ... He had some business in Mexico City and apparently did well financially."[3]

Garrison reported that Greene's son, Lorenzo Thomas Greene, said his father had also told him of the encounter. He said the older man always hoped Gaines would return. But because of his experience with the FBI while active in the civil-rights movement during those years, he did not report it. "There wasn't a lot of trust there," said the son. "Even if my father went to them with that information, I really don't think they would have cared."[3]

Some of Gaines' relatives were willing to accept that he lived out his life in Mexico, as opposed to the alternative scenarios. "It's better than being buried in a basement somewhere—Jimmy Hoffa style," said Paulette Mosby-Smith, one of Gaines' great-nieces. Others believe that would have been against his nature. "It's hard for me to believe that he went to Mexico and accepted a big payoff," George Gaines told Garrison. "That's not the same man who presented himself during the trial. I don't believe he would compromise his integrity like that." Another great-niece, Tracy Berry, who went to law school herself and became a federal prosecutor, agrees:

When you think of those old photos of lynchings and burned bodies, who wouldn't want to think that he lived a full life in Mexico? But based on the love my grandmother and great-grandmother had for their brother and son, that's really hard for me to reconcile. If he wanted to walk away, there are easier ways to do it than to sever ties from the entire family."[3]

She has since told The New York Times that she believes her great-uncle was murdered.[2]

Legacy and honors

Although they had never had Lloyd Gaines declared legally dead, the family nevertheless erected a monument to him in a Missouri cemetery in 1999.[17] "His legacy didn't so much make me want to go to law school," says Tracy Berry. "But I think he did instill the legacy of education in our family. It's expected that you go to college. He started the fight that made it all possible."[3] The Louisville Defender, that city's African American newspaper, expressed similar sentiments in a December 1939 editorial: "[W]hether Gaines has been bribed, intimidated or worse, should certainly have little permanent effect on the struggle for equal rights and social justice in connection with Negro education in the South ... [where] Negroes are already hammering upon the doors of graduate schools hitherto closed to them, with increasing persistence."[18]

"I remember the Gaines case as one of our greatest legal victories," said Thurgood Marshall, who argued Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court and was later that body's first African American justice. "But I have never lost the pain of having so many people spend so much time and money on him, just to have him disappear."[16]

Even without having forced the issue at the Missouri Supreme Court, and without challenging the separate but equal doctrine, Gaines "[made] constitutional compliance in the absence of integration difficult to achieve," according to historian Gary Lavergne. He cited three aspects of the decision:

- First, the Court held that Gaines' right was "a personal and individual one." Gaines was entitled to go to law school regardless of how little demand there was for legal education among African Americans.

- Second, the state could not meet its constitutional burden by sending students out of state. "With Gaines, the idea of using out-of-state scholarships to meet the test of separate but equal legally ended forever and everywhere in the United States," Lavergne says.

- Third, "the Court said that the promise of future equality ... did not make temporary discrimination constitutional."

NAACP lawyer Charles Hamilton Houston had hoped that the effect of similar court rulings that gave segregationist states a choice between full integration or duplication of programs for students of different races would lead many of them to choose the less expensive former option. But without Gaines, he could not carry through the next stage of his plan in the Missouri Supreme Court.[10]

In the short term the abrupt dismissal of the case forced by Gaines' disappearance was a setback for all efforts to legally challenge segregation. The NAACP's resources were depleted after having spent $25,000 ($422,000 in modern dollars[1]) on the case. New plaintiffs, already difficult to find in the depressed economy, couldn't be supported by the organization. Lincoln University School of Law, the only tangible result of the case, was closed by the mid-1950s due to lack of students. When World War II, which had already begun in Europe, swept in the United States two years later, the civil-rights struggle was suspended for the duration.

Houston, ill with the tuberculosis that would end his life a decade later, resigned from the NAACP to return to private practice. Marshall took over for him, a change of personnel that ultimately benefited the desegregation legal effort after the war, when the organization found more plaintiffs and challenged segregationist policies in public graduate schools with cases like Sipuel v. Board of Regents of Univ. of Okla.,[19] Sweatt v. Painter[20] and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents.[21] The University of Missouri School of Law, bowing to pressure from the student body, finally admitted its first African American student in 1951. Three years later the desegregation effort climaxed with Brown, overturning Plessy v. Ferguson and the separate but equal doctrine forever.[16]

At University of Missouri

In the years after Brown, when desegregation became a reality but tensions over it persisted, Gaines' story became a cautionary tale at the University of Missouri. In a 2004 paper, LeeAnn Whites, a professor of Civil War history at the school, repeated a version of it in which Gaines had been on his way to enroll at the school as an undergraduate and had disappeared from a train traveling across the state, with the implication that he was murdered.[22] Gerald M. Boyd, a St. Louis native and Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the New York Times who was one of a few hundred black students at the University of Missouri in the early 1970s, recalls hearing Gaines' story early in his time there, when he was confronted by open displays of racial prejudice such as the university's "Confederate Rock". "Whatever his fate", he wrote in his memoirs, "in the eyes of blacks, the university bore the brunt of the blame."[23]

The University of Missouri, and particularly the University of Missouri School of Law, began recognizing Gaines near the end of the 20th century, despite his never having been formally admitted as a student. It began with a scholarship in his name in 1995. In 2001, the school's African American center was named for Gaines and another early African American who challenged the school's color bar in court. A portrait of Gaines also hangs in a prominent public place in the law school building.[3]

Those honors were supplemented in 2006 when the law school awarded him an honorary degree in Law. The Supreme Court of Missouri, which had denied Gaines' admission almost 70 years before, and the state bar association granted him an honorary posthumous law license. It has been suggested that if Gaines were still alive (he would have turned 95 in 2006) and reappeared, those awards would allow him to practice law in the State of Missouri.[3]

See also

- List of Alpha Phi Alpha brothers

- List of people who disappeared mysteriously

- Lincoln University School of Law

Notes

- ↑ Justice Benjamin Cardozo had recently died, and his seat had not yet been filled, leaving one vacancy on the Court.

References

- 1 2 3 Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Stout, David (July 11, 2009). "A Supreme Triumph, Then Into the Shadows". The New York Times. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Garrison, Chad (April 4, 2007). "The Mystery of Lloyd Gaines". The Riverfront Times (St. Louis, MO: Village Voice Media). Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Katz, Hélèna (2010). Cold Cases: Famous Unsolved Mysteries, Crimes, and Disappearances in America. ABC-CLIO. pp. 157–63. ISBN 978-0-313-37692-4. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Linder, Douglas O. (2000). "Before Brown: Charles H. Houston and the Gaines Case". University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- 1 2 James, Rawn (2010). Root And Branch: Charles Hamilton Houston, Thurgood Marshall, And The Struggle to End Segregation. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-59691-606-7.

- 1 2 3 Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938).

- ↑ Johnson, Kimberley S. (2010). Reforming Jim Crow: Southern Politics and State In The Age Before Brown. Oxford University Press. pp. 153–54. ISBN 978-0-19-538742-1. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- ↑ University of Maryland v. Murray, 169 Md. 478, 182 A. 590, 1936.

- 1 2 3 4 Lavergne, Gary M. (2010). Before Brown: Heman Marion Sweatt, Thurgood Marshall, And the Long Road to Justice. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-0-292-72200-2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 James, 107–13.

- ↑ State ex. rel. Gaines v. Canada, 113 S.W.2d 783, 342 Mo. 121.

- ↑ Gaines. at 349–50, Hughes, C.J.

- ↑ James, 121.

- ↑ White, Walter (1948). A Man Called White: The Autobiography of Walter White. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8203-1698-7. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Crowe, Chris (2008). Thurgood Marshall: Up Close. Penguin. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-670-06228-7. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Zapp, M. (December 21, 2006). "Who was Lloyd Gaines?". Vox (Columbia, MO: Columbia Missourian). Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ↑ "From the Press of the Nation". The Crisis (NAACP). December 1939. p. 372. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ↑ Sipuel v. Board of Regents of Univ. of Okla., 332 U.S. 631 (1948).

- ↑ Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950).

- ↑ McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950).

- ↑ Whites, LeeAnn (2004). "You Can't Change History by Moving A Rock: Gender, Race and the Cultural Politics of Confederate Memorialization". In Waugh, Joan. The Memory of the Civil War in American Culture. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 213–235 [225]. ISBN 978-0-8078-5572-0. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ↑ Boyd, Gerald M. (2010). My Times in Black and White: Race and Power at The New York Times. Chicago Review Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-55652-952-8. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

Further reading

- Clayton, Edward T. (May 1951). "Strange Disappearance of Lloyd Gaines". Ebony magazine.

- Cronan, Patrick (May–June 1974). "A Battle of Yesterday--Integrating Missouri". Focus-Midwest, Issue 64, Vol. 10 (FOCUS/Midwest Publishing Company). pp. 26–27.

- Kelleher, Daniel T. (October 1971). "The Case of Lloyd Lionel Gaines: The Demise of the Separate but Equal Doctrine". Journal of Negro History (Association for the Study of African-American Life and History, Inc.). pp. 262–271.

- Alpha Phi Alpha Men: A Century of Leadership, 2006, Producer/Directors: Alamerica Bank/Rubicon Productions

External links

- Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938)

- A profile of Gaines' attorney, Charles Hamilton Houston, and the Gaines case

- PBS's case page in their history of segregation

- The Lloyd L. Gaines Digital Collection at the University of Missouri School of Law