Isotopes of lithium

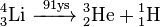

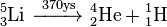

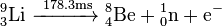

Naturally occurring lithium (chemical symbol Li) (relative atomic mass: 6.941(2)) is composed of two stable isotopes, lithium-6 and lithium-7, with the latter being far more abundant: about 92.5 percent of the atoms. Both of the natural isotopes have an unexpectedly low nuclear binding energy per nucleon (~5.3 MeV) when compared with the adjacent lighter and heavier elements, helium (~7.1 MeV) and beryllium (~6.5 MeV). The longest-lived radioisotope of lithium is lithium-8, which has a half-life of just 838 milliseconds. Lithium-9 has a half-life of 178 milliseconds, and lithium-11 has a half-life of about 8.6 milliseconds. All of the remaining isotopes of lithium have half-lives that are shorter than 10 nanoseconds. The shortest-lived known isotope of lithium is lithium-4, which decays by proton emission with a half-life of about 9.1×10−23 seconds, although the half-life of lithium-3 is yet to be determined, and is likely to be much shorter.

Lithium-7 and lithium-6 are two of the primordial nuclides that were produced in the Big Bang, with lithium-7 to be 10−9 of all primordial nuclides and amount of lithium-6 around 10−13.[1] A small percentage of lithium-6 is also known to be produced by nuclear reactions in certain stars. The isotopes of lithium separate somewhat during a variety of geological processes, including mineral formation (chemical precipitation and ion exchange). Lithium ions replace magnesium or iron in certain octahedral locations in clays, and lithium-6 is sometimes preferred over lithium-7. This results in some enrichment of lithium-7 in geological processes.

Lithium-6 is an important isotope in nuclear physics because when it is bombarded with neutrons, tritium is produced.

Isotope separation

Colex separation

Lithium-6 has a greater affinity than lithium-7 for the element mercury. When an amalgam of lithium and mercury is added to solutions containing lithium hydroxide, the lithium-6 becomes more concentrated in the amalgam and the lithium-7 more in the hydroxide solution.

The colex (column exchange) separation method makes use of this by passing a counter-flow of amalgam and hydroxide through a cascade of stages. The fraction of lithium-6 is preferentially drained by the mercury, but the lithium-7 flows mostly with the hydroxide. At the bottom of the column, the lithium (enriched with lithium-6) is separated from the amalgam, and the mercury is recovered to be reused with fresh raw material. At the top, the lithium hydroxide solution is electrolyzed to liberate the lithium-7 fraction. The enrichment obtained with this method varies with the column length and the flow speed.

Vacuum distillation

Lithium is heated to a temperature of about 550 °C in a vacuum. Lithium atoms evaporate from the liquid surface and are collected on a cold surface positioned a few centimetres above the liquid surface. Since lithium-6 atoms have a greater mean free path, they are collected preferentially.

The theoretical separation efficiency is about 8.0 percent. A multistage process may be used to obtain higher degrees of separation.

Lithium-4

Lithium-4 contains three protons and one neutron. It is the shortest-lived known isotope of lithium, with a half-life of about 9.1×10−23 seconds and decays by proton emission to helium-3.[2] Lithium-4 can be formed as an intermediate in some nuclear fusion reactions.

Lithium-6

Lithium-6 is valuable as the source material for the production of tritium (hydrogen-3) and as an absorber of neutrons in nuclear fusion reactions. Natural lithium contains about 7.5 percent lithium-6, with the rest being lithium-7. Large amounts of lithium-6 have been separated out for placing into hydrogen bombs. The separation of lithium-6 has by now ceased in the large thermonuclear powers, but stockpiles of it remain in these countries. Lithium-6 is one of only three stable isotopes with a spin of 1[3] and has the smallest nonzero nuclear electric quadrupole moment of any stable nucleus.

Lithium-7

Lithium-7 is by far the most-common isotope of natural lithium, making up about 92.5 percent of the atoms. A lithium-7 atom contains three protons, four neutrons, and three electrons, and it is a boson, which means that its total atomic spin is an integer, usually zero. In the Universe, because of its nuclear properties, lithium-7 is less-common than helium, beryllium, carbon, nitrogen, or oxygen, even though the latter four all have heavier nuclei than lithium.

After production of lithium-6, there is lithium left over, which is enriched in lithium-7 and depleted in lithium-6. This Lithium-7 enriched material has been sold commercially, and some of it has been released into the environment. A relative abundance of lithium-7 as high as 35 percent greater than the natural value have been measured in the ground water in a carbonate aquifer underneath the West Valley Creek in Pennsylvania, which is downstream from a lithium processing plant. In the depleted lithium, the relative abundance of lithium-6 can be reduced to as little as 20 percent of its nominal value, giving an atomic mass for the discharged lithium that can range from about 6.94 atomic mass units to about 7.00 a.m.u. Hence the isotopic composition of lithium can vary somewhat depending on its source. An accurate atomic mass for samples of lithium cannot be measured for all sources of lithium.[4]

Lithium-7 finds one use as a part of the molten lithium fluoride in molten salt reactors: liquid-fluoride nuclear reactors. The large neutron-absorption cross-section of lithium-6 (about 940 barns[5]) as compared with the very small neutron cross-section of lithium-7 (about 45 millibarns) makes high separation of lithium-7 from natural lithium a strong requirement for the possible use in lithium-fluoride reactors.

Lithium-7 hydroxide is used for alkalizing of the coolant in pressurized water reactors.[6]

Some lithium-7 has been produced, for a few picoseconds, which contains a lambda particle in its nucleus, whereas an atomic nucleus is generally thought to contain only neutrons, protons, and pions.[7][8]

Lithium-11

Lithium-11 is thought to possess a halo nucleus consisting of a core of three protons and eight neutrons, two of which have a nuclear halo. It has an exceptionally large cross-section of 3.16 fm, comparable to that of 208Pb. It decays by beta emission to 11Be, which then decays in several ways (see table below).

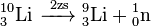

Lithium-12

Lithium-12 has a considerably shorter half-life of around 10 nanoseconds. It decays by neutron emission into 11Li, which decays as mentioned above.

Table

| nuclide symbol |

Z(p) | N(n) | isotopic mass (u) |

half-life | decay mode(s)[9] |

daughter isotope(s)[n 1] |

nuclear spin |

representative isotopic composition (mole fraction) |

range of natural variation (mole fraction) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| excitation energy | |||||||||

| 4Li | 3 | 1 | 4.02719(23) | 91(9)×10−24 s [6.03 MeV] |

p | 3He | |||

| 5Li | 3 | 2 | 5.01254(5) | 370(30)×10−24 s [~1.5 MeV] |

p | 4He | 3/2− | ||

| 6Li | 3 | 3 | 6.015122795(16) | Stable | 1+ | [0.0759(4)] | 0.07714–0.07225 | ||

| 7Li[n 2] | 3 | 4 | 7.01600455(8) | Stable | 3/2− | [0.9241(4)] | 0.92275–0.92786 | ||

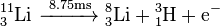

| 8Li | 3 | 5 | 8.02248736(10) | 840.3(9) ms | β− | 8Be[n 3] | 2+ | ||

| 9Li | 3 | 6 | 9.0267895(21) | 178.3(4) ms | β−, n (50.8%) | 8Be[n 4] | 3/2− | ||

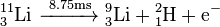

| β− (49.2%) | 9Be | ||||||||

| 10Li | 3 | 7 | 10.035481(16) | 2.0(5)×10−21 s [1.2(3) MeV] |

n | 9Li | (1−,2−) | ||

| 10m1Li | 200(40) keV | 3.7(15)×10−21 s | 1+ | ||||||

| 10m2Li | 480(40) keV | 1.35(24)×10−21 s | 2+ | ||||||

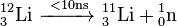

| 11Li[n 5] | 3 | 8 | 11.043798(21) | 8.75(14) ms | β−, n (84.9%) | 10Be | 3/2− | ||

| β− (8.07%) | 11Be | ||||||||

| β−, 2n (4.1%) | 9Be | ||||||||

| β−, 3n (1.9%) | 8Be[n 6] | ||||||||

| β−, α (1.0%) | 7He, 4He | ||||||||

| β−, fission (.014%) | 8Li, 3H | ||||||||

| β−, fission (.013%) | 9Li, 2H | ||||||||

| 12Li | 3 | 9 | 12.05378(107)# | <10 ns | n | 11Li | |||

- ↑ Bold for stable isotopes

- ↑ Produced in Big Bang nucleosynthesis

- ↑ Immediately decays into two 4He atoms for a net reaction of 8Li → 24He + e−

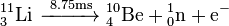

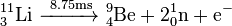

- ↑ Immediately decays into two 4He atoms for a net reaction of 9Li → 24He + 1n + e−

- ↑ Has 2 halo neutrons

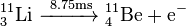

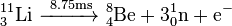

- ↑ Immediately decays into two 4He atoms for a net reaction of 11Li → 24He + 31n + e−

Notes

- The precision of the abundance of isotopes of lithium and the overall atomic weight is limited through variations. The given ranges should be applicable to any normal terrestrial material.

- Exceptional samples of lithium from geology are known in which the isotopic composition lies outside the reported range. The uncertainty in the atomic mass might exceed the stated value for such samples.

- Commercially available samples of lithium may have been subjected to the undisclosed or inadvertent separation of the isotopes. Substantial deviations from the given atomic mass and isotopic composition can be found.

- In depleted lithium (with the 6Li removed), the relative abundance of lithium-6 can be reduced to as little as 20 percent of its normal value, giving the measured atomic mass ranging from 6.94 Da to 7.00 Da.

- The values marked with # are not purely from experimental data, but they are partly or totally estimated from the general trends. The values of spin with weak assignment arguments are enclosed in parentheses.

- Uncertainties are given in concise form in parentheses after the corresponding last digits. Uncertainty values denote one standard deviation from the norm, except for the isotopic compositions and standard atomic masses from the IUPAC that use larger uncertainties.

- The unusual isotope lithium-11 has a nuclear halo of two weakly linked neutrons that explains the important difference in its nuclear radius.

- Nuclide masses are given by IUPAP Commission on Symbols, Units, Nomenclature, Atomic Masses and Fundamental Constants (SUNAMCO)

- Isotope abundances are given by IUPAC Commission on Isotopic Abundances and Atomic Weights

Decay Chains

While β− decay into isotopes of beryllium (often combined with single or multiple neutron emission) is predominant over heavier isotopes of lithium, 10Li and 12Li decay via neutron emission into 9Li and 11Li, respectively, due to their positions above the neutron drip line. Lithium-11 has also been observed to decay via multiple forms of fission. Lighter isotopes of lithium (<6Li) are only known to decay by proton emission. The decay modes of the two isomers of 10Li are unknown.

See also

References

- ↑ BD Fields "The Primordial Lithium Problem", Annual Reviews of Nuclear and Particle Science 2011

- ↑ "Isotopes of Lithium". Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ↑ Chandrakumar, N. (2012). Spin-1 NMR. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 5. ISBN 9783642610899.

- ↑ T. B. Coplen, J. A. Hopple, J. K. Böhlke, H. S. Peiser, S. E. Rieder, H. R. Krouse, K. J. R. Rosman, T. Ding, R. D. Vocke, Jr., K. M. Révész, A. Lamberty, P. Taylor, P. De Bièvre. "Compilation of minimum and maximum isotope ratios of selected elements in naturally occurring terrestrial materials and reagents", U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 01-4222 (2002). As quoted in T. B. Coplen; et al. (2002). "Isotope-Abundance Variations of Selected Elements (IUPAC technical report)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry 74 (10): 1987–2017. doi:10.1351/pac200274101987.

- ↑ Norman E. Holden (January–February 2010). "The Impact of Depleted 6Li on the Standard Atomic Weight of Lithium". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ↑ Managing Critical Isotopes: Stewardship of Lithium-7 Is Needed to Ensure a Stable Supply, GAO-13-716 // U.S. Government Accountability Office, 19 September 2013; pdf

- ↑ John Emsley (2001). Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford University Press. pp. 234–239. ISBN 978-0-19-850340-8.

- ↑ Geoff Brumfiel (1 March 2001). "The Incredible Shrinking Nucleus". Physical Review Focus 7. doi:10.1103/PhysRevFocus.7.11.

- ↑ "Universal Nuclide Chart". Nucleonica. Retrieved 2012-09-27. (registration required (help)).

- Isotope masses from:

- G. Audi; A. H. Wapstra; C. Thibault; J. Blachot; O. Bersillon (2003). "The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties" (PDF). Nuclear Physics A 729: 3–128. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- Isotopic compositions and standard atomic masses from:

- J. R. de Laeter; J. K. Böhlke; P. De Bièvre; H. Hidaka; H. S. Peiser; K. J. R. Rosman; P. D. P. Taylor (2003). "Atomic weights of the elements. Review 2000 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry 75 (6): 683–800. doi:10.1351/pac200375060683.

- M. E. Wieser (2006). "Atomic weights of the elements 2005 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry 78 (11): 2051–2066. doi:10.1351/pac200678112051. Lay summary.

- Half-life, spin, and isomer data selected from the following sources. See editing notes on this article's talk page.

- G. Audi; A. H. Wapstra; C. Thibault; J. Blachot; O. Bersillon (2003). "The NUBASE evaluation of nuclear and decay properties" (PDF). Nuclear Physics A 729: 3–128. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- National Nuclear Data Center. "NuDat 2.1 database". Brookhaven National Laboratory. Retrieved September 2005.

- N. E. Holden (2004). "Table of the Isotopes". In D. R. Lide. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (85th ed.). CRC Press. Section 11. ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

External links

Lewis, G. N.; MacDonald, R. T. (1936). "The Separation of Lithium Isotopes". Journal of the American Chemical Society 58 (12): 2519–2524. doi:10.1021/ja01303a045.

| Isotopes of helium | Isotopes of lithium | Isotopes of beryllium |

| Table of nuclides | ||

| Isotopes of the chemical elements | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 H |

2 He | ||||||||||||||||

| 3 Li |

4 Be |

5 B |

6 C |

7 N |

8 O |

9 F |

10 Ne | ||||||||||

| 11 Na |

12 Mg |

13 Al |

14 Si |

15 P |

16 S |

17 Cl |

18 Ar | ||||||||||

| 19 K |

20 Ca |

21 Sc |

22 Ti |

23 V |

24 Cr |

25 Mn |

26 Fe |

27 Co |

28 Ni |

29 Cu |

30 Zn |

31 Ga |

32 Ge |

33 As |

34 Se |

35 Br |

36 Kr |

| 37 Rb |

38 Sr |

39 Y |

40 Zr |

41 Nb |

42 Mo |

43 Tc |

44 Ru |

45 Rh |

46 Pd |

47 Ag |

48 Cd |

49 In |

50 Sn |

51 Sb |

52 Te |

53 I |

54 Xe |

| 55 Cs |

56 Ba |

|

72 Hf |

73 Ta |

74 W |

75 Re |

76 Os |

77 Ir |

78 Pt |

79 Au |

80 Hg |

81 Tl |

82 Pb |

83 Bi |

84 Po |

85 At |

86 Rn |

| 87 Fr |

88 Ra |

|

104 Rf |

105 Db |

106 Sg |

107 Bh |

108 Hs |

109 Mt |

110 Ds |

111 Rg |

112 Cn |

113 Uut |

114 Fl |

115 Uup |

116 Lv |

117 Uus |

118 Uuo |

| |

57 La |

58 Ce |

59 Pr |

60 Nd |

61 Pm |

62 Sm |

63 Eu |

64 Gd |

65 Tb |

66 Dy |

67 Ho |

68 Er |

69 Tm |

70 Yb |

71 Lu | ||

| |

89 Ac |

90 Th |

91 Pa |

92 U |

93 Np |

94 Pu |

95 Am |

96 Cm |

97 Bk |

98 Cf |

99 Es |

100 Fm |

101 Md |

102 No |

103 Lr | ||

| |||||||||||||||||