Iranian languages

| Iranian | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity: | Iranian peoples |

| Geographic distribution: | Southwest Asia, Caucasus, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and western South Asia |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Proto-language: | Proto-Iranian |

| Subdivisions: | |

| ISO 639-5: | ira |

| Linguasphere: | 58= (phylozone) |

| Glottolog: | iran1269[1] |

|

Countries and autonomous subdivisions where an Iranian language has official status or is spoken by a majority | |

The Iranian languages or Iranic languages[2][3] form a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages, which in turn are a branch of the Indo-European language family. The speakers of Iranian languages are known as Iranian peoples. Historical Iranian languages are grouped in three stages: Old Iranian (until 400 BCE), Middle Iranian (400 BCE – 900 CE), and New Iranian (since 900 CE). Of the Old Iranian languages, the better understood and recorded ones are Old Persian (a language of Achaemenid Iran) and Avestan (the language of the Avesta). Middle Iranian languages included Middle Persian (a language of Sassanid Iran), Parthian, and Bactrian.

As of 2008, there were an estimated 150–200 million native speakers of Iranian languages.[4] Ethnologue estimates there are 86 Iranian languages,[5][6] the largest amongst them being Persian, Pashto, Kurdish, and Balochi.

Term

The term Iranian is applied to any language which descends from the ancestral Proto-Iranian language.[7] Iranian derives from the Persian and Sanskrit origin word Arya.

The use of the term for the Iranian language family was introduced in 1836 by Christian Lassen.[8] Robert Needham Cust used the term Irano-Aryan in 1878,[9] and Orientalists such as George Abraham Grierson and Max Müller contrasted Irano-Aryan (Iranian) and Indo-Aryan (Indic). Some recent scholarship, primarily in German, has revived this convention.[10][11][12][13]

Proto-Iranian

All Iranian languages are descended from a common ancestor, Proto-Iranian. In turn, and together with Proto-Indo-Aryan and the Nuristani languages, Proto-Iranian descends from a common ancestor Proto-Indo-Iranian. The Indo-Iranian languages are thought to have originated in Central Asia. The Andronovo culture is the suggested candidate for the common Indo-Iranian culture ca. 2000 BC.

It was situated precisely in the western part of Central Asia that borders present-day Russia (and present-day Kazakhstan). It was in relative proximity to the other satem ethno-linguistic groups of the Indo-European family, like Thracian, Balto-Slavic and others, and to common Indo-European's original homeland (more precisely, the steppes of southern Russia to the north of the Caucasus), according to the reconstructed linguistic relationships of common Indo-European.

Proto-Iranian thus dates to some time after Proto-Indo-Iranian break-up, or the early second millennium BCE, as the Old Iranian languages began to break off and evolve separately as the various Iranian tribes migrated and settled in vast areas of southeastern Europe, the Iranian plateau, and Central Asia.

Innovations of Proto-Iranian compared to Proto-Indo-Iranian include (from Witzel, 2001):[14]

- *s other than *[ʃ] turns into *[h]

- *bʰ, *dʰ, *gʰ merge into *b, *d, *g

- Fricativization of voiceless stops

- *p, *t, *k become *f, *θ, *x before another consonant

- in all positions, *pʰ, *tʰ, *kʰ become *f, *θ, *x

Old Iranian

The multitude of Middle Iranian languages and peoples indicate that great linguistic diversity must have existed among the ancient speakers of Iranian languages. Of that variety of languages/dialects, direct evidence of only two have survived. These are:

- Avestan, the two languages/dialects of the Avesta, i.e. the liturgical texts of Zoroastrianism.

- Old Persian, the native language of a south-western Iranian people known as Persians.[15]

Indirectly attested Old Iranian languages are discussed below.

Old Persian is the Old Iranian dialect as it was spoken in south-western Iran by the inhabitants of Parsa, who also gave their name to their region and language. Genuine Old Persian is best attested in one of the three languages of the Behistun inscription, composed circa 520 BC, and which is the last inscription (and only inscription of significant length) in which Old Persian is still grammatically correct. Later inscriptions are comparatively brief, and typically simply copies of words and phrases from earlier ones, often with grammatical errors, which suggests that by the 4th century BC the transition from Old Persian to Middle Persian was already far advanced, but efforts were still being made to retain an "old" quality for official proclamations.

The other directly attested Old Iranian dialects are the two forms of Avestan, which take their name from their use in the Avesta, the liturgical texts of indigenous Iranian religion that now goes by the name of Zoroastrianism but in the Avesta itself is simply known as vohu daena (later: behdin). The language of the Avesta is subdivided into two dialects, conventionally known as "Old (or 'Gathic') Avestan", and "Younger Avestan". These terms, which date to the 19th century, are slightly misleading since 'Younger Avestan' is not only much younger than 'Old Avestan', but also from a different geographic region. The Old Avestan dialect is very archaic, and at roughly the same stage of development as Rigvedic Sanskrit. On the other hand, Younger Avestan is at about the same linguistic stage as Old Persian, but by virtue of its use as a sacred language retained its "old" characteristics long after the Old Iranian languages had yielded to their Middle Iranian stage. Unlike Old Persian, which has Middle Persian as its known successor, Avestan has no clearly identifiable Middle Iranian stage (the effect of Middle Iranian is indistinguishable from effects due to other causes).

In addition to Old Persian and Avestan, which are the only directly attested Old Iranian languages, all Middle Iranian languages must have had a predecessor "Old Iranian" form of that language, and thus can all be said to have had an (at least hypothetical) "Old" form. Such hypothetical Old Iranian languages include Carduchi (the hypothetical predecessor to Kurdish) and Old Parthian. Additionally, the existence of unattested languages can sometimes be inferred from the impact they had on neighbouring languages. Such transfer is known to have occurred for Old Persian, which has (what is called) a "Median" substrate in some of its vocabulary.[16] Also, foreign references to languages can also provide a hint to the existence of otherwise unattested languages, for example through toponyms/ethnonyms or in the recording of vocabulary, as Herodotus did for what he called "Scythian".

Isoglosses

Conventionally, Iranian languages are grouped in "western" and "eastern" branches.[17] These terms have little meaning with respect to Old Avestan as that stage of the language may predate the settling of the Iranian peoples into western and eastern groups. The geographic terms also have little meaning when applied to Younger Avestan since it isn't known where that dialect (or dialects) was spoken either. Certain is only that Avestan (all forms) and Old Persian are distinct, and since Old Persian is "western", and Avestan was not Old Persian, Avestan acquired a default assignment to "eastern". Confusing the issue is the introduction of a western Iranian substrate in later Avestan compositions and redactions undertaken at the centers of imperial power in western Iran (either in the south-west in Persia, or in the north-west in Nisa/Parthia and Ecbatana/Media).

Two of the earliest dialectal divisions among Iranian indeed happen to not follow the later division into Western and Eastern blocks. These concern the fate of the Proto-Indo-Iranian first-series palatal consonants, *ć and *dź:[18]

- Avestan and most other Iranian languages have deaffricated and depalatalized these consonants, and have *ć > s, *dź > z.

- Old Persian, however, has fronted these consonants further: *ć > θ, *dź > *ð > d.

As a common intermediate stage, it is possible to reconstruct depalatalized affricates: *c, *dz. (This coincides with the state of affairs in the neighboring Nuristani languages.) A further complication however concerns the consonant clusters *ćw and *dźw:

- Avestan and most other Iranian languages have shifted these clusters to sp, zb.

- In Old Persian, these clusters yield s, z, with loss of the glide *w, but without further fronting.

- The Saka language, attested in the Middle Iranian period, and its modern relative Wakhi fail to fit into either group: in these, palatalization remains, and similar glide loss as in Old Persian occurs: *ćw > š, *dźw > ž.

A division of Iranian languages in at least three groups during the Old Iranian period is thus implied:

- Persid (Old Persian and its descendants)

- Sakan (Saka, Wakhi, and their Old Iranian ancestor)

- Central Iranian (all other Iranian languages)

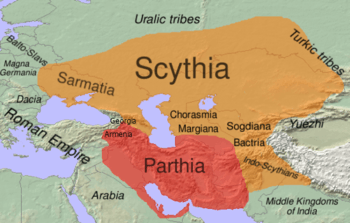

It is possible that other distinct dialect groups were already in existence during this period. Good candidates are the hypothethical ancestor languages of Alanian/Scytho-Sarmatian subgroup of Scythian in the far northwest; and the hypothetical "Old Parthian" (the Old Iranian ancestor of Parthian) in the near northwest, where original *dw > *b (paralleling the development of *ćw).

Middle Iranian languages

What is known in Iranian linguistic history as the "Middle Iranian" era is thought to begin around the 4th century BCE lasting through the 9th century. Linguistically the Middle Iranian languages are conventionally classified into two main groups, Western and Eastern.

The Western family includes Parthian (Arsacid Pahlavi) and Middle Persian, while Bactrian, Sogdian, Khwarezmian, Saka, and Old Ossetic (Scytho-Sarmatian) fall under the Eastern category. The two languages of the Western group were linguistically very close to each other, but quite distinct from their eastern counterparts. On the other hand, the Eastern group was an areal entity whose languages retained some similarity to Avestan. They were inscribed in various Aramaic-derived alphabets which had ultimately evolved from the Achaemenid Imperial Aramaic script, though Bactrian was written using an adapted Greek script.

Middle Persian (Pahlavi) was the official language under the Sasanian dynasty in Iran. It was in use from the 3rd century CE until the beginning of the 10th century. The script used for Middle Persian in this era underwent significant maturity. Middle Persian, Parthian and Sogdian were also used as literary languages by the Manichaeans, whose texts also survive in various non-Iranian languages, from Latin to Chinese. Manichaean texts were written in a script closely akin to the Syriac script.[19]

New Iranian languages

Teal: regional co-official/de facto status.

Following the Islamic Conquest of Persia (Iran), there were important changes in the role of the different dialects within the Persian Empire. The old prestige form of Middle Iranian, also known as Pahlavi, was replaced by a new standard dialect called Dari as the official language of the court. The name Dari comes from the word darbâr (دربار), which refers to the royal court, where many of the poets, protagonists, and patrons of the literature flourished. The Saffarid dynasty in particular was the first in a line of many dynasties to officially adopt the new language in 875 CE. Dari may have been heavily influenced by regional dialects of eastern Iran, whereas the earlier Pahlavi standard was based more on western dialects. This new prestige dialect became the basis of Standard New Persian. Medieval Iranian scholars such as Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa (8th century) and Ibn al-Nadim (10th century) associated the term "Dari" with the eastern province of Khorasan, while they used the term "Pahlavi" to describe the dialects of the northwestern areas between Isfahan and Azerbaijan, and "Pârsi" ("Persian" proper) to describe the Dialects of Fars. They also noted that the unofficial language of the royalty itself was yet another dialect, "Khuzi", associated with the western province of Khuzestan.

The Islamic conquest also brought with it the adoption of Arabic script for writing Persian and much later, Kurdish, Pashto and Balochi. All three were adapted to the writing by the addition of a few letters. This development probably occurred some time during the second half of the 8th century, when the old middle Persian script began dwindling in usage. The Arabic script remains in use in contemporary modern Persian. Tajik script was first Latinised in the 1920s under the then Soviet nationality policy. The script was however subsequently Cyrillicized in the 1930s by the Soviet government.

The geographical regions in which Iranian languages were spoken were pushed back in several areas by newly neighbouring languages. Arabic spread into some parts of Western Iran (Khuzestan), and Turkic languages spread through much of Central Asia, displacing various Iranian languages such as Sogdian and Bactrian in parts of what is today Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. In Eastern Europe, mostly comprising the territory of modern-day Ukraine, southern European Russia, and parts of the Balkans, the core region of the native Scythians, Sarmatians, and Alans had been decisively been taken over as a result of absorption and assimilation (e.g. Slavicisation) by the various Proto-Slavic population of the region, by the 6th century AD. This resulted in the displacement and extinction of the once predominant Scythian languages of the region. Sogdian's close relative Yaghnobi barely survives in a small area of the Zarafshan valley east of Samarkand, and Saka as Ossetic in the Caucasus, which is the sole remnant of the once predominant Scythian languages in Eastern Europe proper and large parts of the North Caucasus. Various small Iranian languages in the Pamirs survive that are derived from Eastern Iranian.

Comparison table

| English | Zaza | Kurdish (Northern/Central) | Pashto | Tati | Balochi | Mazandarani | Persian | Middle Persian | Parthian | Old Persian | Avestan | Ossetian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beautiful | řind, delal, ciwan | řind, nayab, bedew, delal/cwan | x̌kūlay, x̌āista | xojir | sharr, soherâ, mah rang | xoşgel | zibā/xuš-čehr(e) | hučihr, hužihr | hužihr | naiba | vahu-, srîra | ræsughd |

| blood | gunî | xwîn/xwên | wīna | xevn | hon | xun | xūn | xōn | gōxan | vohuni- | tug | |

| bread | nan | nan | ḍoḍəi, məṛəi | nun | nān, nagan | nun | nān | nān | nān | dzul | ||

| bring | ardene | anîn/hênan/weranîn, hawirdin | (rā)wṛəl | vârden, biyordon | âurten, yārag, ārag | biyârden | āwurdan, biyār ("(you) bring!") | āwurdan, āwāy-, āwar-, bar- | āwāy-, āwar-, bar- | bara- | bara, bar- | xæssyn |

| brother | bira | brader, bra, bira | wror | bərâr | brāt, brās | birâr | barādar | brād, brâdar | brād, brādar | brātar | brātar- | æfsymær |

| come | amayene | hatin | rā tləl | biyâmiyan | āhag, āyag,hatin | biyamona, enen, biyâmuen | āmadan | āmadan, awar | awar, čām | āy-, āgam | āgam- | cæwyn |

| cry | berbayene | girîn, giryan | žəṛəl | bərma | greewag, greeten | birme | gerīstan/gerīye | griy-, bram- | barmâdan | kæwyn | ||

| dark | tarî | tarî/tarîk | skəṇ, skaṇ, tyara | ul, gur, târica, târek | thár | sîyo, sîyu | tārīk | tārīg/k | tārīg, tārēn | sâmahe, sâma | tar | |

| daughter | kêna | keç, kîj, qîz, dot/kiç, kîj, kenişk, düet (pehlewanî) | lūr | titiye, dətar | dohtir, duttag | kîjâ, deter | doxtar | duxtar | duxt, duxtar | duxδar | čyzg (Iron), kizgæ (Digor) | |

| day | řoce/řoje/řoze | řoj | wrəd͡z (rwəd͡z) | revj, ruz | roç | ruz | rūz | rōz | raucah- | raocah- | bon | |

| do | kerdene | kirin/kirdin | kawəl | korden | kanag, kurtin | hâkerden | kardan | kardan | kartan | kạrta- | kәrәta- | kænyn |

| door | ber, kêber/çêber | derî, derge/derke, derga | wər | darvâca | gelo, darwāzag | dar, loş | dar | dar | dar, bar | duvara- | dvara- | dwar |

| die | merdene | mirin/mirdin | mrəl | bamarden | mireg | bamerden | murdan | murdan | mạriya- | mar- | mælyn | |

| donkey | her | ker | xər | astar, xar | har,her, kar | xar | xar | xar | xæræg | |||

| egg | hak | hêk/hêlke, tuxm | hagəi | merqâna, karxâ | heyg, heyk, ā morg | merqâne, tîm , balî | toxm, xāya ("testicle") | toxmag, xâyag | taoxmag, xâyag | taoxma- | ajk | |

| earth | erd | zemîn, zewî, ʿerz, erd | d͡zməka (md͡zəka) | zemin | zemin | zamîn, bene | zamīn | zamīg | zamīg | zam- | zãm, zam, zem | zæxx |

| evening | şan | êvar/êware | māx̌ām (māš̥ām) | nemâzi sar | begáh | nemâşun | begáh | ēvārag | êbêrag | izær | ||

| eye | çim | çav/çaw/çaş | stərga | coš | ch.hem, chem | çəş, bəj | čashm | čašm | čašm | čaša- | čašman- | cæst |

| father | pî, baw, babî, bawk | bav/bab, bawk, ba | plār | piya, piyar, dada | pit, piss | pîyer | pedar, pidar | pidar | pid | pitar | pitar | fyd |

| fear | ters | tirs | wēra (yara), bēra | târs | turs, terseg | taşe-vaşe | tars | tars | tars | tạrsa- | tares- | tas |

| fiancé | waşte, nîşanbîyaye | xwestî, nîşankirî, dezgîran | čənghol [masculine], čənghəla [feminine] | numuzâ | nāmzād | numze | nāmzād | - | - | usag | ||

| fine | weş | xweş | x̌a (š̥a), səm, ṭik (Urdu origin) |

xojir | wash, hosh | xâr | xoš, xūb, beh | dārmag | srîra | xorz, dzæbæx | ||

| finger | gişte, engişte, bêçike | til/qamik, bêçî, pêçîk, engust, pence | gwəta | anquš | lenkutk, mordâneg,changol | angus | angošt | angust | dišti- | ængwyldz | ||

| fire | adir | agir/awir, ahir | wōr (ōr) | taš | âch, âs | taş | ātaš, āzar | âdur, âtaxsh | ādur | âç- | âtre-/aêsma- | art |

| fish | mase | masî | kəb | mâyi | māhi, māhig | mâhî | māhi | māhig | māsyāg | masya | kæsag | |

| food / eat | werdene | xwarin / xwardin | xwāṛə, xurāk / xwaṛəl | harden | warag, warâk | xerâk / baxârden | xordan / xurāk / ġhazā | parwarz / xwâr, xwardīg | parwarz / xwâr | hareθra / ad-, at- | xærinag | |

| go | şîyayene | çûn, řoştin, řoyiştin | tləl | šiyen, bišiyan | jwzzegh, shutin | şunen / burden | raftan | raftan | ay- | ai- | ay-, fra-vaz | cæwyn |

| god | heq, homa | Yezdan, xwedê, xuda, xodê, xwa(y) | xwədāi | xədâ | hwdâ | xedâ | xudā | yazdān | baga- | baya- | xwycaw | |

| good | baş, rind | baş, řind/baş, çak | x̌ə (š̥ə) | xâr, xojir | jawáin, šarr,zabr | xâr | xub, nīkū, beh | xūb, nêkog | vahu- | vohu, vaŋhu- | xorz | |

| grass | vaş | giya/gya | wāx̌ə (wāš̥ə) | vâš | rem, sabzag | vâş | sabzeh, giyāh | giyâ | giya | urvarâ | kærdæg | |

| great | girs/gird, pîl, xişn | mezin, gir/gewre, mezin | lōy, stər | pilla | mastar, mazan,tuh | gat | bozorg,setabr | wuzurg, pīl | vazraka- | uta-, avañt | styr | |

| hand | dest | dest, des | lās | bâl | dast | das, bāl | dast | dast | dast | dasta- | zasta- | k'ux / arm |

| head | ser | ser | sər | kalla | saghar,sar, sarag | kalle | sar | sar | sairi | sær | ||

| heart | zerrî | dil/dił/dir(Erbil)/zil | zṛə | dəl | dil, hatyr | del | del | dil | dil | aηhuš | zærdæ | |

| horse | estor | hesp/esp, hês(t)ir | ās [male], aspa [female] | asb, astar | asp | as, asb | asp | asp, stōr | asp, stōr | aspa | aspa- | bæx |

| house | keye | mal/mał, xanu, xang | kor | kiya | log, dawâr,ges | sere, xene | xāna | xânag | demâna-, nmâna- | xædzar | ||

| hunger | vêşan | birçî/birsî | lwəga | vašnâ, vešir, gosna | shudhagh | veşnâ | gorosna | gursag, shuy | strong | |||

| language (also tongue) | ziwan, zon | ziman, ziwan | žəba | zobun, zəvân | zevān, zobān | zebun, zivun | zabān | zuwān | izβān | hazâna- | hizvā- | ævzag |

| laugh | huyayene | kenîn/pêkenîn, kenîn | xandəl/xənda | xurəsen, bexandastan | khendegh, hendeg | rîk, baxendesten | xandidan | xandīdan, xanda | karta | Syaoθnâvareza- | xudyn | |

| life | cu/cuye, jewiyaene | jiyan | žwəndūn, žwənd | zindәgi | zendegih, zind | zindegî | zendegi | zīndagīh, zīwišnīh | žīwahr, žīw- | gaêm, gaya- | card | |

| man | merd, lacek | merd, mêr, pîyaw | səṛay, mēṛə | mardak, miarda | merd | mard(î) | mard | mard | mard | martiya- | mašîm, mašya | adæjmag |

| moon | aşme, meng (for month) | heyv, meh/mang (for month) | spūgməi (spōẓ̌məi) | mâng | máh | ma, munek | mâh | māh | māh | mâh- | måŋha- | mæj |

| mother | maye, daye, dayike | dayek, dayk, daye, mak | mōr | mâr, mâya, nana | mât, mâs | mâr | mâdar | mâdar | dayek | mâtar | mâtar- | mad |

| mouth | fek | dev, fek/dem | xūla (xʷəla) | duxun, dâ:ân | dap | dâhun, lâmîze | dahân | dahân, rumb | åŋhânô, âh, åñh | dzyx | ||

| name | name | nav/naw, nam, nêw | nūm | num | nâm | num | nâm | nâm | nâman | nãman | nom | |

| night | şewe | şev/şew | špa | šö, šav | šap, shaw | şow | shab | shab | xšap- | xšap- | æxsæv | |

| open | akerdene | vekirin/kirdinewe | prānistəl | vâ-korden | pabožagh, paç | vâ-hekârden | bâz-kardan | abâz-kardan, višādag | būxtaka- | būxta- | gom kænyn | |

| peace | aştî | aştî, aramî | rōɣa, t͡sōkāləi | dinj | ârâm | âştî | âshti, ârâmeš, ârâmî | âštih, râmīšn | râm, râmīšn | šiyâti- | râma- | fidyddzinad |

| pig | xoz, xonz | beraz, | soḍər, xənd͡zir (Arabic) | xu, xuyi, xug | khug | xî | xūk | xūk | hū | xwy | ||

| place | ja | jî, jih, je(jega), ga | d͡zāi | yâga | hend, jâgah | jâ | jâh/gâh | gâh | gâh | gâθu- | gâtu-, gâtav- | ran |

| read | wendene | xwendin/xwêndin | lwastəl, kōtəl | baxânden | wánagh | baxinden, baxundesten | xândan | xwândan | kæsyn | |||

| say | vatene | gotin/gutin, witin | wayəl | vâten, baguten | gushagh | baowten | goftan, gap(-zadan) | guftan, gōw-, wâxtan | gōw- | gaub- | mrû- | dzuryn |

| sister | waye | xweh, xweşk, xoşk, xuşk, xoyşk | xōr (xʷōr) | xâke, xâv, xâxor, xuâr | gwhâr | xâxer | xâhar/xwâhar | xwahar | x ̌aŋhar- "sister" | xo | ||

| small | qic/qicik, wurdî/hurdî | biçûk, giçke, qicik, hûr | kūčnay, waṛ(ū)kay | qijel, qolâ | gwand, hurd | peçik, biçuk, xurd | kuchak, kam, xurd, rîz | kam, rangas | kam | kamna- | kamna- | chysyl |

| son | qij, lac/laj | kur, law/kuř | d͡zoy (zoy) | pur, zâ | baç, phusagh | piser/rîkâ | pesar, baça | pur, pusar | puhr | puça | pūθra- | fyrt |

| soul | gan | gan, giyan, rewan, revan | sā | rəvân | rawân | ravân | rūwân, gyân | rūwân, gyân | urvan- | ud | ||

| spring | wisar/wesar/usar | behar, bihar, wehar | spərlay | vâ:âr | bhârgâh | vehâr | bahâr | wahâr | vâhara- | θūravâhara- | ||

| tall | berz | bilind/berz | lwəṛ, ǰəg | pilla | bwrz, borz | bilen(d) | boland / bârez | buland, borz | bârež | barez- | bærzond | |

| ten | des | deh/de | ləs | da | deh | da | dah | dah | datha | dasa | dæs | |

| three | hîrê | sê, sisê | drē | so | sey | se | se | sê | hrē | çi- | θri- | ærtæ |

| village | dewe | gund, dêhat, dê | kəlay | döh, da | helk, kallag, dê | dih, male | deh, wis | wiž | dahyu- | vîs-, dahyu- | vîs | qæw |

| want | waştene | xwastin, xwestin, wîstin | ɣ(ʷ)ux̌təl | begovastan, jovastan | lotagh | bexâsten | xâstan | xwâstan | fændyn | |||

| water | awe | av/aw | obə/ūbə | âv, ö | âp | ow | âb/aw | âb | aw | âpi | avô- | don |

| when | key | kengê/key, kengê | kəla | key | kadi,ked | ke | key | kay | ka | čim- | kæd | |

| wind | va | ba, wa (pehlewanî) | siləi | vâ | gwáth | vâ | bâd | wâd | wa | vâta- | dymgæ / wad | |

| wolf | verg | gur/gurg, wurg | lewə, šarmux̌ (šarmuš̥) | varg | gurkh | verg | gorg | gurg | varka- | vehrka | birægh | |

| woman | cenî | jin | x̌əd͡za (š̥əd͡za) | zeyniye, zenak | jan,jinik | zan | zan | zan | žan | gǝnā, γnā, ǰaini-, | sylgojmag / us | |

| year | serre | sal/sał | kāl | sâl | sâl | sâl | sâl | sâl | θard | ýâre, sarәd | az | |

| yes / no | ya, belê / ne, ney | erê, bełê, a / na, ne | Hao, ao, wō / na, ya | ahan / na | ere / na | are / nâ | baleh, ârē, hā / na, née | ōhāy / ne | hâ / ney | yâ / nay, mâ | yâ / noit, mâ | o / næ |

| yesterday | vizêr | duh/dwênê, duêke | parūn | azira, degiru | zí | dîruz | diruz | dêrûž | diya(ka) | zyō | znon | |

| English | Zaza | Kurdish (Northern/Central) | Pashto | Tati | Balochi | Mazandarani | Persian | Middle Persian | Parthian | Old Persian | Avestan | Ossetian |

See also

References

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Iranian". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Toward a Typology of European Languages edited by Johannes Bechert, Giuliano Bernini, Claude Buridant

- ↑ Persian Grammar: History and State of its Study by Gernot L. Windfuhr

- ↑ Windfuhr, Gernot. The Iranian languages. Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

- ↑ "Ethnologue report for Iranian". Ethnologue.com.

- ↑ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005). "Report for Iranian languages". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Fifteenth ed.) (Dallas: SIL International).

- ↑ (Skjærvø 2006)

- ↑ Lassen, Christian. 1936. Die altpersischen Keil-Inschriften von Persepolis. Entzifferung des Alphabets und Erklärung des Inhalts. Bonn: Weber. S. 182.

This was followed by Wilhelm Geiger in his Grundriss der Iranischen Philologie (1895). Friedrich von Spiegel (1859), Avesta, Engelmann (p. vii) used the spelling Eranian. - ↑ Cust, Robert Needham. 1878. A sketch of the modern languages of the East Indies. London: Trübner.

- ↑ Dani, Ahmad Hasan. 1989. History of northern areas of Pakistan. Historical studies (Pakistan) series. National Institute of Historical and Cultural Research.

"We distinguish between the Aryan languages of Iran, or Irano-Aryan, and the Aryan languages of India, or Indo-Aryan. For the sake of brevity, Iranian is commonly used instead of Irano-Aryan". - ↑ Lazard, Gilbert. 1977. Preface in: Oranskij, Iosif M. Les langues iraniennes. Traduit par Joyce Blau.

- ↑ Schmitt, Rüdiger. 1994. Sprachzeugnisse alt- und mitteliranischer Sprachen in Afghanistan in: Indogermanica et Caucasica. Festschrift für Karl Horst Schmidt zum 65. Geburtstag. Bielmeier, Robert und Reinhard Stempel (Hrg.). De Gruyter. S. 168–196.

- ↑ Lazard, Gilbert. 1998. Actancy. Empirical approaches to language typology. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-015670-9, ISBN 978-3-11-015670-6

- ↑ Michael Witzel (2001): Autochthonous Aryans? The evidence from Old Indian and Iranian texts. Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7(3): 1–115.

- ↑ Roland G. Kent: "Old Persion: Grammar Texts Lexicon". Part I, Chapter I: The Linguistic Setting of Old Persian. American Oriental Society, 1953.

- ↑ (Skjaervo 2006) vi(2). Documentation.

- ↑ Nicholas Sims-Williams, Iranica, under entry: Eastern Iranian languages

- ↑ Windfuhr, Gernot (2009). "Dialectology and Topics". The Iranian Languages. Routledge. pp. 18–21.

- ↑ Mary Boyce. 1975. A Reader in Manichaean Middle Persian and Parthian, p. 14.

Notes

- Bailey, H. W. (1979). Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge University Press. 1979. 1st Paperback edition 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-14250-2.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (ed.) (1989). Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum (in German). Wiesbaden: Reichert. ISBN 3-88226-413-6.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1996). "Iranian languages". Encyclopedia Iranica 7. Costa Mesa: Mazda. pp. 238–245.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.) (1996). "Iran". Encyclopedia Iranica 7. Costa Mesa: Mazda.

- Frye, Richard N. (1996). "Peoples of Iran". Encyclopedia Iranica 7. Costa Mesa: Mazda.

- Windfuhr, Gernot L. (1995). "Cases in Iranian languages and dialects". Encyclopedia Iranica 5. Costa Mesa: Mazda. pp. 25–37.

- Lazard, Gilbert (1996). "Dari". Encyclopedia Iranica 7. Costa Mesa: Mazda.

- Henning, Walter B. (1954). "The Ancient language of Azarbaijan". Transactions of the Philological Society 53 (1): 157. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1954.tb00282.x.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2001). "The Iranian Language Family".

- Skjærvø, Prods Oktor (2006). "Encyclopædia Iranica" 13.

|contribution=ignored (help) - Delshad, Farshid (2010). Georgica et Irano-Semitica (PDF). Ars Poetica. Deutscher Wissenschaftsverlag DWV. ISBN 978-3-86888-004-5.

- Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (2006). The Oxford introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European world. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929668-2

External links

- Society for Iranian Linguistics

- Kurdish and other Iranic Languages

- Iranian EFL Journal

- Audio and video recordings for over 50 languages spoken in Iran

- Iranian language tree in Russian, identical with above classification.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|