Semi-empirical mass formula

In nuclear physics, the semi-empirical mass formula (SEMF) (sometimes also called Weizsäcker's formula, or the Bethe–Weizsäcker formula, or the Bethe–Weizsäcker mass formula to distinguish it from the Bethe–Weizsäcker process) is used to approximate the mass and various other properties of an atomic nucleus from its number of protons and neutrons. As the name suggests, it is based partly on theory and partly on empirical measurements. The theory is based on the liquid drop model proposed by George Gamow, which can account for most of the terms in the formula and gives rough estimates for the values of the coefficients. It was first formulated in 1935 by German physicist Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, and although refinements have been made to the coefficients over the years, the structure of the formula remains the same today.[1][2]

The SEMF gives a good approximation for atomic masses and several other effects, but does not explain the appearance of magic numbers of protons and neutrons, and the extra binding-energy and measure of stability that are associated with these numbers of nucleons.

| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

| Nucleus · Nucleons (p, n) · Nuclear force · Nuclear structure · Nuclear reaction |

|

Nuclear models and stability |

|

Nucleosynthesis topics Nuclear fusion Processes: Stellar · Big Bang · Supernova Nuclides: Primordial · Cosmogenic · Artificial |

|

Scientists |

The liquid drop model and its analysis

The liquid drop model in nuclear physics treats the nucleus as a drop of incompressible nuclear fluid. It was first proposed by George Gamow and then developed by Niels Bohr and John Archibald Wheeler. The nucleus is made of nucleons (protons and neutrons), which are held together by the strong nuclear force. This is very similar to the structure of spherical liquid drop made of microscopic molecules. This is a crude model that does not explain all the properties of the nucleus, but does explain the spherical shape of most nuclei. It also helps to predict the nuclear binding energy and to assess how much is available for consumption.

Mathematical analysis of the theory delivers an equation which attempts to predict the binding energy of a nucleus in terms of the numbers of protons and neutrons it contains. This equation has five terms on its right hand side. These correspond to the cohesive binding of all the nucleons by the strong nuclear force, a surface energy term, the electrostatic mutual repulsion of the protons, an asymmetry term (derivable from the protons and neutrons occupying independent quantum momentum states) and a pairing term (partly derivable from the protons and neutrons occupying independent quantum spin states).

If we consider the sum of the following five types of energies, then the picture of a nucleus as a drop of incompressible liquid roughly accounts for the observed variation of binding energy of the nucleus:

Volume energy. When an assembly of nucleons of the same size is packed together into the smallest volume, each interior nucleon has a certain number of other nucleons in contact with it. So, this nuclear energy is proportional to the volume.

Surface energy. A nucleon at the surface of a nucleus interacts with fewer other nucleons than one in the interior of the nucleus and hence its binding energy is less. This surface energy term takes that into account and is therefore negative and is proportional to the surface area.

Coulomb Energy. The electric repulsion between each pair of protons in a nucleus contributes toward decreasing its binding energy.

Asymmetry energy (also called Pauli Energy). An energy associated with the Pauli exclusion principle. Were it not for the Coulomb energy, the most stable form of nuclear matter would have the same number of neutrons as protons, since unequal numbers of neutrons and protons imply filling higher energy levels for one type of particle, while leaving lower energy levels vacant for the other type.

Pairing energy. An energy which is a correction term that arises from the tendency of proton pairs and neutron pairs to occur. An even number of particles is more stable than an odd number.

The formula

In the following formulae, let A be the total number of nucleons, Z the number of protons, and N the number of neutrons, so that A=Z+N.

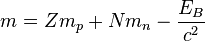

The mass of an atomic nucleus is given by

where  and

and  are the rest mass of a proton and a neutron, respectively, and

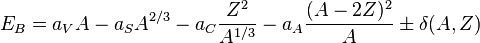

are the rest mass of a proton and a neutron, respectively, and  is the binding energy of the nucleus. The semi-empirical mass formula states that the binding energy will take the following form:

is the binding energy of the nucleus. The semi-empirical mass formula states that the binding energy will take the following form:

Each of the terms in this formula has a theoretical basis, as will be explained below. The coefficients  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and a coefficient that appears in the formula for

and a coefficient that appears in the formula for  are determined empirically.

are determined empirically.

Terms

Volume term

The term  is known as the volume term. The volume of the nucleus is proportional to A, so this term is proportional to the volume, hence the name.

is known as the volume term. The volume of the nucleus is proportional to A, so this term is proportional to the volume, hence the name.

The basis for this term is the strong nuclear force. The strong force affects both protons and neutrons, and as expected, this term is independent of Z. Because the number of pairs that can be taken from A particles is  , one might expect a term proportional to

, one might expect a term proportional to  . However, the strong force has a very limited range, and a given nucleon may only interact strongly with its nearest neighbors and next nearest neighbors. Therefore, the number of pairs of particles that actually interact is roughly proportional to A, giving the volume term its form.

. However, the strong force has a very limited range, and a given nucleon may only interact strongly with its nearest neighbors and next nearest neighbors. Therefore, the number of pairs of particles that actually interact is roughly proportional to A, giving the volume term its form.

The coefficient  is smaller than the binding energy of the nucleons to their neighbours

is smaller than the binding energy of the nucleons to their neighbours  , which is of order of 40 MeV. This is because the larger the number of nucleons in the nucleus, the larger their kinetic energy is, due to the Pauli exclusion principle. If one treats the nucleus as a Fermi ball of

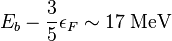

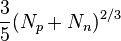

, which is of order of 40 MeV. This is because the larger the number of nucleons in the nucleus, the larger their kinetic energy is, due to the Pauli exclusion principle. If one treats the nucleus as a Fermi ball of  nucleons, with equal numbers of protons and neutrons, then the total kinetic energy is

nucleons, with equal numbers of protons and neutrons, then the total kinetic energy is  , with

, with  the Fermi energy which is estimated as 28 MeV. Thus the expected value of

the Fermi energy which is estimated as 28 MeV. Thus the expected value of  in this model is

in this model is  , not far from the measured value.

, not far from the measured value.

Surface term

The term  is known as the surface term. This term, also based on the strong force, is a correction to the volume term.

is known as the surface term. This term, also based on the strong force, is a correction to the volume term.

The volume term suggests that each nucleon interacts with a constant number of nucleons, independent of A. While this is very nearly true for nucleons deep within the nucleus, those nucleons on the surface of the nucleus have fewer nearest neighbors, justifying this correction. This can also be thought of as a surface tension term, and indeed a similar mechanism creates surface tension in liquids.

If the volume of the nucleus is proportional to A, then the radius should be proportional to  and the surface area to

and the surface area to  . This explains why the surface term is proportional to

. This explains why the surface term is proportional to  . It can also be deduced that

. It can also be deduced that  should have a similar order of magnitude as

should have a similar order of magnitude as  .

.

Coulomb term

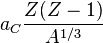

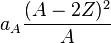

The term  or

or  is known as the Coulomb or electrostatic term.

is known as the Coulomb or electrostatic term.

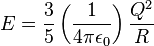

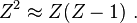

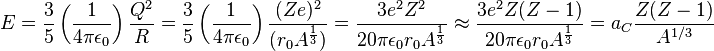

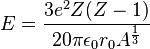

The basis for this term is the electrostatic repulsion between protons. To a very rough approximation, the nucleus can be considered a sphere of uniform charge density. The potential energy of such a charge distribution can be shown to be

where Q is the total charge and R is the radius of the sphere. Identifying Q with  , and noting as above that the radius is proportional to

, and noting as above that the radius is proportional to  , we get close to the form of the Coulomb term. However, because electrostatic repulsion will only exist for more than one proton,

, we get close to the form of the Coulomb term. However, because electrostatic repulsion will only exist for more than one proton,  becomes

becomes  . The value of

. The value of  can be approximately calculated using the equation above:

can be approximately calculated using the equation above:

Quantum charge integers:

Integration by substitution:

Potential energy of charge distribution:

Electrostatic Coulomb constant:

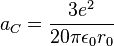

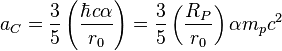

The value of  using the fine structure constant:

using the fine structure constant:

where  is the fine structure constant and

is the fine structure constant and  is the radius of a nucleus, giving

is the radius of a nucleus, giving  to be approximately 1.25 femtometers.

to be approximately 1.25 femtometers.  is the proton Compton radius and

is the proton Compton radius and  the proton mass. This gives

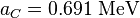

the proton mass. This gives  an approximate theoretical value of 0.691 MeV, not far from the measured value.

an approximate theoretical value of 0.691 MeV, not far from the measured value.

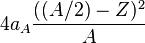

Asymmetry term

The term  or

or  is known as the asymmetry term. Note that as

is known as the asymmetry term. Note that as  , the parenthesized expression can be rewritten as

, the parenthesized expression can be rewritten as  . The form

. The form  is used to keep the dependence on A explicit, as will be important for a number of uses of the formula.

is used to keep the dependence on A explicit, as will be important for a number of uses of the formula.

The theoretical justification for this term is more complex. The Pauli exclusion principle states that no two fermions can occupy exactly the same quantum state in an atom. At a given energy level, there are only finitely many quantum states available for particles. What this means in the nucleus is that as more particles are "added", these particles must occupy higher energy levels, increasing the total energy of the nucleus (and decreasing the binding energy). Note that this effect is not based on any of the fundamental forces (gravitational, electromagnetic, etc.), only the Pauli exclusion principle.

Protons and neutrons, being distinct types of particles, occupy different quantum states. One can think of two different "pools" of states, one for protons and one for neutrons. Now, for example, if there are significantly more neutrons than protons in a nucleus, some of the neutrons will be higher in energy than the available states in the proton pool. If we could move some particles from the neutron pool to the proton pool, in other words change some neutrons into protons, we would significantly decrease the energy. The imbalance between the number of protons and neutrons causes the energy to be higher than it needs to be, for a given number of nucleons. This is the basis for the asymmetry term.

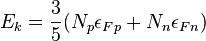

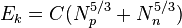

The actual form of the asymmetry term can again be derived by modelling the nucleus as a Fermi ball of protons and neutrons. Its total kinetic energy is

where  ,

,  are the numbers of protons and neutrons and

are the numbers of protons and neutrons and  ,

,  are their Fermi energies. Since the latter are proportional to

are their Fermi energies. Since the latter are proportional to  and

and  , respectively, one gets

, respectively, one gets

for some constant C.

for some constant C.

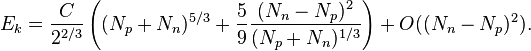

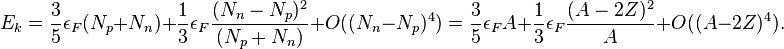

The leading expansion in the difference  is then

is then

At the zeroth order expansion the kinetic energy is just the Fermi energy  multiplied by

multiplied by  . Thus we get

. Thus we get

The first term contributes to the volume term in the semi-empirical mass formula, and the second term is minus the asymmetry term (remember the kinetic energy contributes to the total binding energy with a negative sign).

is 38 MeV, so calculating

is 38 MeV, so calculating  from the equation above, we get only half the measured value. The discrepancy is explained by our model not being accurate: nucleons in fact interact with each other, and are not spread evenly across the nucleus. For example, in the shell model, a proton and a neutron with overlapping wavefunctions will have a greater strong interaction between them and stronger binding energy. This makes it energetically favourable (i.e. having lower energy) for protons and neutrons to have the same quantum numbers (other than isospin), and thus increase the energy cost of asymmetry between them.

from the equation above, we get only half the measured value. The discrepancy is explained by our model not being accurate: nucleons in fact interact with each other, and are not spread evenly across the nucleus. For example, in the shell model, a proton and a neutron with overlapping wavefunctions will have a greater strong interaction between them and stronger binding energy. This makes it energetically favourable (i.e. having lower energy) for protons and neutrons to have the same quantum numbers (other than isospin), and thus increase the energy cost of asymmetry between them.

One can also understand the asymmetry term intuitively, as follows. It should be dependent on the absolute difference  , and the form

, and the form  is simple and differentiable, which is important for certain applications of the formula. In addition, small differences between Z and N do not have a high energy cost. The A in the denominator reflects the fact that a given difference

is simple and differentiable, which is important for certain applications of the formula. In addition, small differences between Z and N do not have a high energy cost. The A in the denominator reflects the fact that a given difference  is less significant for larger values of A.

is less significant for larger values of A.

Pairing term

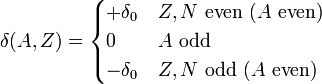

The term  is known as the pairing term (possibly also known as the pairwise interaction). This term captures the effect of spin-coupling. It is given by:[4]

is known as the pairing term (possibly also known as the pairwise interaction). This term captures the effect of spin-coupling. It is given by:[4]

where

Due to Pauli exclusion principle the nucleus would have a lower energy if the number of protons with spin up were equal to the number of protons with spin down. This is also true for neutrons. Only if both Z and N are even can both protons and neutrons have equal numbers of spin up and spin down particles. This is a similar effect to the asymmetry term.

The factor  is not easily explained theoretically. The Fermi ball calculation we have used above, based on the liquid drop model but neglecting interactions, will give an

is not easily explained theoretically. The Fermi ball calculation we have used above, based on the liquid drop model but neglecting interactions, will give an  dependence, as in the asymmetry term. This means that the actual effect for large nuclei will be larger than expected by that model. This should be explained by the interactions between nucleons; For example, in the shell model, two protons with the same quantum numbers (other than spin) will have completely overlapping wavefunctions and will thus have greater strong interaction between them and stronger binding energy. This makes it energetically favourable (i.e. having lower energy) for protons to pair in pairs of opposite spin. The same is true for neutrons.

dependence, as in the asymmetry term. This means that the actual effect for large nuclei will be larger than expected by that model. This should be explained by the interactions between nucleons; For example, in the shell model, two protons with the same quantum numbers (other than spin) will have completely overlapping wavefunctions and will thus have greater strong interaction between them and stronger binding energy. This makes it energetically favourable (i.e. having lower energy) for protons to pair in pairs of opposite spin. The same is true for neutrons.

Calculating the coefficients

The coefficients are calculated by fitting to experimentally measured masses of nuclei. Their values can vary depending on how they are fitted to the data. Several examples are as shown below, with units of megaelectronvolts.

| Least-squares fit | Wapstra[5] | Rohlf[6] | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

15.8 | 14.1 | 15.75 |

|

18.3 | 13 | 17.8 |

|

0.714 | 0.595 | 0.711 |

|

23.2 | 19 | 23.7 |

|

12 | n/a | n/a |

(even-even) (even-even) |

n/a | -33.5 | +11.18 |

(odd-odd) (odd-odd) |

n/a | +33.5 | -11.18 |

(even-odd) (even-odd) |

n/a | 0 | 0 |

The semi-empirical mass formula provides a good fit to heavier nuclei, and a poor fit to very light nuclei, especially 4He. This is because the formula does not consider the internal shell structure of the nucleus. For light nuclei, it is usually better to use a model that takes this structure into account.

Examples for consequences of the formula

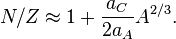

By maximizing B(A,Z) with respect to Z, we find the best neutrons to protons ratio N/Z for a given atomic weight A.[6] We get

This is roughly 1 for light nuclei, but for heavy nuclei the ratio grows in good agreement with nature.

By substituting the above value of Z back into B one obtains the binding energy as a function of the atomic weight, B(A). Maximizing B(A)/A with respect to A gives the nucleus which is most strongly bound, i.e. most stable. The value we get is A = 63 (copper), close to the measured values of A = 62 (nickel) and A = 58 (iron).

Notes

- ↑ von Weizsäcker, C. F. (1935). "Zur Theorie der Kernmassen". Zeitschrift für Physik (in German) 96 (7–8): 431–458. Bibcode:1935ZPhy...96..431W. doi:10.1007/BF01337700.

- ↑ Bailey, D. "Semi-empirical Nuclear Mass Formula". PHY357: Strings & Binding Energy. University of Toronto. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

- ↑ Oregon State University. "Nuclear Masses and Binding Energy Lesson 3" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ Krane, K. (1988). Introductory Nuclear Physics. John Wiley & Sons. p. 68. ISBN 0-471-85914-1.

- ↑ Wapstra, A. H. (1958). "Atomic Masses of Nuclides". External Properties of Atomic Nuclei. Springer. pp. 1–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45901-6_1. ISBN 978-3-642-45902-3.

- 1 2 Rohlf, J. W. (1994). Modern Physics from α to Z0. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0471572701.

References

- Freedman, R.; Young, H. (2004). Sears and Zemanskey's University Physics with Modern Physics (11th ed.). pp. 1633–1634. ISBN 0-8053-8768-4.

- Liverhant, S. E. (1960). Elementary Introduction to Nuclear Reactor Physics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 58–62. LCCN 60011725.

- Choppin, G.; Liljenzin, J.-O.; Rydberg, J. (2002). "Nuclear Mass and Stability" (PDF). Radiochemistry and Nuclear Chemistry (3rd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 41–57. ISBN 978-0-7506-7463-8.

External links

- Nuclear liquid drop model

- The semi-empirical mass formula

- Liquid drop model in the hyperphysics online reference at Georgia State University.

- Liquid drop model with parameter fit from First Observations of Excited States in the Neutron Deficient Nuclei 160,161W and 159Ta, Alex Keenan, PhD thesis, University of Liverpool, 1999 (HTML version).