Lions led by donkeys

"Lions led by donkeys" is a phrase popularly used to describe the British infantry of World War I and to blame the generals who led them. The contention is that the brave soldiers (lions) were sent to their deaths by incompetent and indifferent leaders (donkeys).[1] The phrase was the source of the title of one of the most scathing examinations of British First World War generals, The Donkeys - a study Western Front offensives - by politician and writer of military histories Alan Clark.[2] The book was representative of much First World War history produced in the 1960s and was not outside the mainstream—Basil Liddell Hart vetted Clark's drafts[3]—and helped to form a popular view of the First World War (in the English-speaking world) in the decades that followed. However, the work's viewpoint of incompetent military leaders was never accepted by mainstream historians, and both the book and its viewpoint have been subject to attempts at revisionism.[4] A good example of this would be general Haig, who led most of the troops from the battle of the Somme to their deaths.

Origin of the phrase

The origin of the phrase pre-dates the First World War. Plutarch attributed to Chabrias the saying that "an army of deer commanded by a lion is more to be feared than an army of lions commanded by a deer".[5][6] An ancient Arabian proverb says "An army of sheep led by a lion would defeat an army of lions led by a sheep". During the Crimean War a letter was reportedly sent home by a British soldier quoting a Russian officer who had said that British soldiers were "lions commanded by donkeys".[7] This was immediately after the failure to storm the fortress of Sevastopol which, if true, would take the saying back to 1854–5.

These and other Crimean War references were included in the British Channel 4 TV’s The Crimean War series (1997) and accompanying book (Michael Hargreave Mawson, expert reader).[better reference needed]

Karl Marx and Frederick Engels used the phrase on September 27, 1855, in an article published in Neue Oder-Zeitung, No. 457 (October 1, 1855), on the British military's strategic mistakes and failings during the fall of Sevastopol, and particularly General Simpson's military leadership of the assault on the Redan rampart.

The joke making the rounds of the Russian army, that "L'armée anglaise est une armée des lions, commandee par des ânes" (The English army is an army of lions led by asses) has been thoroughly vindicated by the assault on Redan.[8]

The Times reportedly recycled the phrase as "lions led by donkeys" with reference to French soldiers during the Franco-Prussian War,

Unceasingly they [the French forces] had had drummed into them the utterances of The Times: "You are lions led by jackasses." Alas! The very lions had lost their manes. (On leur avait répété tout le long de la campagne le mot du Times: – "Vous êtes des lions conduits par des ânes! – Hélas! les lions mêmes avaient perdus leurs crinières") Francisque Darcey (sometimes Sarcey).[9]

There were numerous examples of its use during the First World War, referring to both the British and the Germans.[1] In Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear: Russia's War with Japan (2003), Richard Connaughton attributed a later quotation to Colonel J. M. Grierson (later Sir James Grierson) in 1901, when reporting on the Russian contingent to the Boxer Rebellion, describing them as 'lions led by asses'.[10]

In the Second World War Erwin Rommel said it to the British after he captured Tobruk. [11]

Attribution to First World War German or British officers

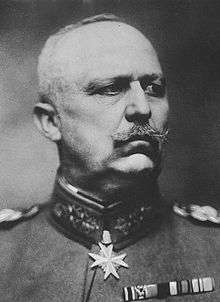

Evelyn, Princess Blücher, an Englishwoman who lived in Berlin during the First World War, in her memoir published in 1921, recalled hearing German general Erich Ludendorff praise the British for their bravery and remembered hearing first hand the following statement from the German General Headquarters (Grosses Hauptquartier): "The English Generals are wanting in strategy. We should have no chance if they possessed as much science as their officers and men had of courage and bravery. They are lions led by donkeys."[12]

The phrase Lions Led by Donkeys was used as a title for a book published in 1927, by Captain P. A. Thompson. The subtitle of this book was "Showing how victory in the Great War was achieved by those who made the fewest mistakes."[13]

Alan Clark based the title of his book "The Donkeys" (1961) on the phrase. Prior to publication in a letter to Hugh Trevor Roper, he asked "English soldiers, lions led by donkeys etc - can you remember who said that?" Liddell Hart, although he did not dispute the veracity of the quote, had asked Clark for its origins.[14] Whatever Trevor Roper's reply, Clark eventually used the phrase as an epigraph to The Donkeys and attributed it to a conversation between German generals Erich Ludendorff and Max Hoffmann,

The conversation was supposedly published in the memoirs of General Erich von Falkenhayn, the German chief of staff between 1914 and 1916 but the exchange and the memoirs remain untraced.[1] A correspondent to The Daily Telegraph in July 1963, wrote that librarians in London and Stuttgart had not traced the quotation and a letter to Clark was unanswered.[15] Clark was equivocal about the source for the dialogue for many years, although in 2007 a friend Euan Graham, recalled a conversation in the mid-sixties, when Clark on being challenged as to the provenance of the dialogue, looked sheepish and said "well I invented it". At one time Clark claimed that Liddell Hart had given him the quote (unlikely as Hart had asked him where it came from) and Clark's biographer believes he invented the Ludendorff-Hoffmann attribution.[16] This invention has provided an opportunity for critics of The Donkeys to condemn the work. Richard Holmes, wrote of The Donkeys

... it contained a streak of casual dishonesty. Its title is based on the "Lions led by Donkeys" conversation between Hindenburg [sic] and Ludendorff. There is no evidence whatever for this: none. Not a jot or scintilla. Liddell Hart, who had vetted Clark’s manuscript, ought to have known it.[17]

Popular culture

The musical Oh, What a Lovely War! (1963) and the comedy television series Blackadder Goes Forth (1989) are two well-known works of popular culture, depicting the war as a matter of incompetent donkeys sending noble (or sometimes ignoble, in the case of Blackadder) lions to their doom. Such works are in the literary tradition of the war poets like Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon and Erich Maria Remarque's novel (and subsequent film) All Quiet on the Western Front, which have been criticised by revisionists such as Brian Bond for having given rise to what he considered the myth and conventional wisdom of the Great War as futile. What Bond found most objectionable was how in the 1960s, the works of Remarque and the Trench Poets slipped into the nasty caricature of lions led by donkeys, while the more complicated history of the war receded into the background.[18]

Producers of television documentaries about the war have had to grapple with the "lions led by donkeys" interpretive frame since the 1960s. The 1964 seminal and award-winning BBC Television The Great War has been described as taking a moderate approach, with co-scriptwriter John Terraine fighting against what he viewed as an oversimplification, while Liddell Hart resigned as an advising historian to the series, in an open letter to The Times, in part over a dispute with Terraine, claiming that he minimised the faults of the High Command on The Somme and other concerns regarding the treatment of Third Ypres. The Great War was viewed by about a fifth of the adult population in Britain and the production of documentaries on the war has continued ever since. While recent documentaries such as Channel 4's 2003 The First World War, have confronted the popular image of lions led by donkeys, by reflecting current scholarship presenting more nuanced portrayals of British leaders and more balanced appraisals of the difficulties faced by the High Commands of all the combatants, they have been viewed by far fewer members the public than either 1964's The Great War or comedies such as Blackadder.[19]

Criticism

Brian Bond, in editing a 1991 collection of essays on First World War history, expressed the collective desire of the authors to move beyond "popular stereotypes of The Donkeys", while acknowledging that serious leadership mistakes were made and that the authors would do little to rehabilitate the reputations of the senior commanders on The Somme.[4] Hew Strachan quoted Maurice Genevoix for the proposition "[i]f it is neither desirable nor good that the professional historian prevail over the veteran; it is also not good that the veteran prevail over the historian" and then proceeded to take Liddell Hart to task for "suppressing the culminating battles of the war", thus "allow[ing] his portrayal of British generals to assume an easy continuum, from incompetence on the Western Front to conservatism in the 1920s...."[4] While British leadership at the beginning of the war made costly mistakes, by 1915–16 the General Staff were making great efforts to lessen British casualties through better tactics (night attacks, creeping barrages and air power) and weapons technology (poison gas and later the arrival of the tank). British generals were not the only ones to make mistakes about the nature of modern conflict: Russian armies too suffered badly during the first years of the war, most notably at the Battle of Tannenberg. To many generals who had fought colonial wars during the second half of the 19th century, where the Napoleonic concepts of discipline and pitched battles were still successful, fighting another highly industrialized power with equal and sometimes superior technology required an extreme change in thinking.

Later, Strachan, in reviewing Aspects of the British experience of the First World War edited by Michael Howard, observed that "In the study of the First World War in particular, the divide between professionals and amateurs has never been firmly fixed". He points out that revisionists take strong exception to the amateurs, particularly in the media, with whom they disagree, while at the same time Gary Sheffield welcomes to the revisionist cause, the work of many "hobby"-ists who only later migrated to academic study.[20] Gordon Corrigan, for example, did not even consider Clark to be a historian.[21] The phrase "lions led by donkeys" has been said to have produced a false, or at least very incomplete, picture of generalship in the First World War, giving an impression of Generals as "château Generals", living in splendour, indifferent to the sufferings of the men under their command, only interested in cavalry charges and cowards. One historian wrote that "the idea that they were indifferent to the sufferings of their men is constantly refuted by the facts, and only endures because some commentators wish to perpetuate the myth that these generals, representing the upper classes, did not give a damn what happened to the lower orders".[22] Some current academic opinion has described this school of thought as "discredited".[23][24] Strachan quotes Gavin Stamp, who bemoans "a new generation of military historians", who seem as "callous and jingoistic" as Haig, while himself referring to the "ill-informed diatribes of Wolff and Clark".[20]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Rees, Nigel. Brewer's Famous Quotations. Weidenfeld & Nicolson (2006) (personal communication from author including text from book 2007-11-15)

- 1 2 Clark, A. (1961). The Donkeys. Morrow. p. front-papers. OCLC 245804594.

- ↑ Ion Trewin, Alan Clark: The Biography Weidenfield & Nicholson 2009, p 160.

- 1 2 3 Brian Bond, ed. (1991). The First World War and British Military History. Oxford Clarendon Press. pp. 6–12, 41, 47. ISBN 978-0-19-822299-6.

[D]espite the saturation coverage of the First World War in the 1960s, little was produced of lasting scholarly value because there was so little attempt to place the war in historical perspective; books such as The Donkeys and films such as Oh, What a Lovely War tell us as much about the spirit of the 1960s as about the period supposedly portrayed.

- ↑ Plutarch; Morgan, Matthew (1718). Plutarch's Morals. London: W. Taylor. p. 204.

- ↑ Plutarch, Regum et imperatorum apophthegmata 47.3

- ↑ Tyrrell, Henry (1855). The History of the War with Russia: Giving Full Details of the Operations of the Allied Armies, Volumes 1-3. p. 256.

- ↑ Marx, K and Engels, F (1980). The Reports of Generals Simson, Pelissier and Niel. Collected Works, Volume 14: Progress Publishers, Moscow. pp. p.542. ISBN 085315435X.

- ↑ Terraine, 1980 pp. 170–171

- ↑ Connaughton 2003, p. 32

- ↑ The Guinness History of the British Army (1993) by John Pimlott, p. 138

- ↑ Evelyn, Princess Blücher (1921). An English Wife in Berlin. London: Constable. p. 211. OCLC 252298574.

- ↑ P. A. Thompson (1927). Lions Led by Donkeys Showing How Victory in the Great War was Achieved by Those Who Made the Fewest Mistakes. London: T. W. Laurie. OCLC 4326703.

- ↑ Ion Trewin, Alan Clark: The Biography Weidenfield & Nicholson 2009, p. 168

- ↑ Terraine, 1980, p. 170

- ↑ Trewin 2009, pp. 182–189

- ↑ Richard Holmes War of Words: The British Army and the Western Front CRF Prize Lecture 26 & 28 May 2003 Aberdeen and Edinburgh

- ↑ Matthew Stewart (2003). "Review Great War History, Great War Myth: Brian Bond's Unquiet Western Front and the Role of Literature and Film" (pdf). War, Literature and the Arts (United States Air Force Academy) 15: 345, 349–351. ISSN 2169-7914. Retrieved 2010-07-26.

- ↑ Emma Hanna (2009). The Great War on the Small Screen: Representing the First World War in Contemporary Britain. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 21, 26–28, 35. ISBN 978-0-7486-3389-0.

- 1 2 Hew Strachan Back to the trenches – Why can't British historians be less insular about the First World War? The Sunday Times November 5, 2008

- ↑ Corrigan, p. 213. "Alan Clark was an amusing writer, a brilliant story teller and bon viveur. British political life is the poorer for his passing, but he cannot be described as a historian".

- ↑ Neillands, Robin (1998). The Great War Generals on the Western Front. London: Robinson. p. 514. ISBN 1-85487-900-6.

- ↑ Simpson, Andy, Directing Operations: British Corps Command on the Western Front, p. 181.

- ↑ Sheffield, Gary. The Somme, pp. xiv–xv.

Further reading

- Mitchell, S. B. T. (2013). An Inter-Disciplinary Study of Learning in the 32nd Division on the Western Front, 1916–1918 (PhD). Birmingham University. OCLC 894593861. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

External links

- The Donkeys (1962) archive.org

- The Western Front Association: British Military Leadership In The First World War, John Terraine, 1991

- University of Birmingham Centre for First World War Studies: Lions Led By Donkeys

- National archives: Learning Curve WW1

- BBC History's World War's in Depth: World War One