Linguistic landscape

Linguistic landscape is the "visibility and salience of languages on public and commercial signs in a given territory or region" (Landry and Bourhis 1997:23). Linguistic landscape has been described as being "somewhere at the junction of sociolinguistics, sociology, social psychology, geography, and media studies".[1] It is a concept used in sociolinguistics as scholars study how languages are visually used in multilingual societies. For example, some public signs in Jerusalem are in Hebrew, English, and Arabic (Spolsky and Cooper 1991, Ben-Rafael, Shohamy, Amara, and Trumper-Hecht 2006).

Development of the field of study

Studies of the linguistic landscape have been published from studies done around the world. The field of study is relatively recent; "the linguistic landscapes paradigm has evolved rapidly and while it has a number of key names associated with it, it currently has no clear orthodoxy or theoretical core" (Sebba 2010:73). An entire issue of the International Journal of Multilingualism (3.1 in 2006) was devoted to the subject. Also, the journal World Englishes published a themed issue of five papers as a "Symposium on World Englishes and Linguistic Landscapes: Five Perspectives" (2012, vol. 31.1). Similarly, an entire issue of the International Journal of the Sociology of Language (228 in 2014) was devoted to the subject, including looking at signs that show influences from one language on another language. There is now an academic journal devoted to this topic, titled Linguistic Landscape: An International Journal, from John Benjamins. There is also a series of academic conferences on the study of linguistic landscape.[2]

Because "the methodologies employed in the collection and categorisation of written signs is still controversial",[3] basic research questions are still being discussed, such as: "do small, hand-made signs count as much as large, commercially made signs?". The original technical scope of "linguistic landscape" involved plural languages, and almost all writers use it in that sense, but Papen has applied the term to the way public writing is used in a monolingual way in a German city[4] and Heyd has applied the term to the ways that English is written, and people's reactions to these ways.[5]

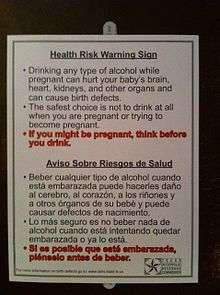

The languages used in public signs indicate what languages are locally relevant, or give evidence of what languages are becoming locally relevant (Kasanga 2012). In many multilingual countries, multilingual signs and packaging are taken for granted, especially as merchants try to attract as many customers as possible or people realize that they serve a multilingual community. In other places, it is a matter of law, as in Quebec, where signs cannot be in English only, but must include French (Bill 101, Charte de la langue française). In Texas, some signs are required to be in English and Spanish, such as warning signs about consuming alcohol while pregnant.

In some cases, the signs themselves are multilingual signs, reflecting an expected multilingual readership. In other cases, there are monolingual signs in different languages, written in relevant languages found within a multilingual community. Backhaus even points out that some signs are not meant to be understood so much as to appeal to readers via a more prestigious language (2007:58).

Some signs are spelled to convey the aura of another language (sometimes genuinely spelled as in the other language, others times fictionally), but are still meant to be understood by monolinguals. For example, some signs in English are spelled in a way that conveys the aura of German or French, but are still meant to be understood by monolingual English speakers.

The study of linguistic landscape also examines such patterns as which languages are used for which types of institutions (e.g. country club, hospital, ethnic grocery store), which languages are used for more expensive/cheaper items (new cars or used cars), or which languages are used for more expensive/cheaper services (e.g. pool cleaning or washing machine repair). Also, linguistic landscapes can be studied across an area, to see which neighborhoods have signs in which languages.

Linguistic landscape can also be applied to the study of competing scripts for a single language. For example, after the breakup of the Soviet Union, some signs in Mongolia were erected in the traditional Mongolian script, not just Cyrillic (Grivelet 2001). Similarly, in some Cherokee speaking communities, street signs and other public signage is written with the Cherokee syllabary (Bender 2008). Also, license plates in Greek Cyprus have been printed with Greek or Roman letters in different eras.[6]

The study of the linguistic landscape can also show evidence of the presence and roles of different languages through history.[7] [8] Some early work on a specific form of linguistic landscape was done in cemeteries used by immigrant communities,[9] some languages being carved "long after the language ceased to be spoken" in the communities.[10]

In addition to larger public signage, some who study linguistic landscapes are now including the study of other public objects with multilingual texts, such as banknotes in India which are labeled in over a dozen languages.[11]

Examples

-

Indian bank note with multiple languages

-

The three-language (Tamil, English and Hindi) name board at the Tirusulam railway station in South India. Almost all railway stations in India have signs in three or more languages (English, Hindi and the local language).

-

Spanish-English sign at Cathedral Santuario de Guadalupe in Dallas, Texas; the congregation has both English and Spanish speakers.

-

Bilingual sign in a Quebec supermarket with markedly predominant French text.

-

Monolingual biscriptal street sign in Belarusian in Minsk, Belarus.

-

English and Cherokee sign: Cherokee visually prominent but less functional.

-

English and Spanish hospital directory, English prominent, in USA.

-

English and French sign in Louisiana, French written to indicate historical link, not so much to be understood

-

Spanish church sign in Georgia, USA, addressed entirely to Spanish readers.

-

Washing machine repairman advertising on his truck, in English and Spanish, English on top, Texas

-

Product originally labeled in English; bilingual warning base added for any hospital visitors & workers who are Spanish-dominant.

-

Bilingual sign, in three scripts, near Hungary-Ukraine border.

-

Sign in Israel written in two locally relevant languages, plus international language.

-

Sign in Roman script but Hebrew words, a hostel in Haifa, Israel catering to European gentiles

-

This Spanish sign was advertising a mobile home for rent in a largely Hispanic neighborhood in Texas. The broader community is predominantly non-Spanish speaking.

-

Commercial signs in section of Houston, Texas with large Asian population.

-

Predominantly Spanish sign in Texas church working to welcome Spanish speakers, near English version of same sign

-

Spanish language billboard in Dallas, TX, but product itself labeled in English.

-

Chinese sign on restaurant in America, conveying Chinese aura but not propositional content.

-

Trilingual, biscriptal sign in Nunavut, Canada, using Canadian Aboriginal Syllabic script

-

Hebrew gravestone in Germany

-

German gravestone in Israel

-

Apartheid era trilingual sign in South Africa

-

Gujarati and English sign on shop in English-speaking town in America, a Hindu talisman in the Gujarati language

-

Manila Oriental Market, grocery store in Daly, CA catering to many customers of Asian origin

-

A library sign in English with Spanish below, in Texas. The city has many Spanish speakers moving in, so the public library has added Spanish books and Spanish signs.

-

Statue of Mariano Datahan, early promoter of the Eskayan language and script, labeled in Eskayan with its unique script

-

Vietnamese temple in Seattle, sign in three languages

-

Tombstone for Gurkha soldier who served in British army, in Gurkha and English

-

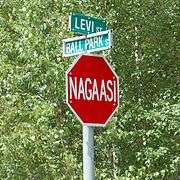

Mi'kmaq language stop sign in Elsipogtog First Nation, Canada, street names in English

-

Sign on building for Burmese refugees in USA

-

Warning sign in Jerusalem, Hebrew on top

-

Signs in both Japanese and Portuguese in the Homi housing complex in the Homigaoka district of Toyota City, Japan

-

In Fredericksburg, Texas founded by Germans, using German image for tourism. German part of the sign only for a German aura.

-

"Learn Danish" banner in Danish and German, in Flensburg, Germany where it is an officially recognised regional language.

-

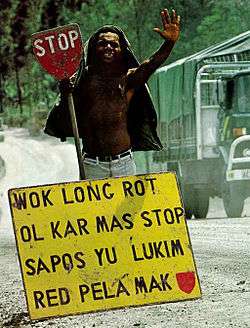

In Papua New Guinea, stop sign in English, more detailed warning in Tok pisin

-

Sign in Macau with street name in both Chinese and Portuguese

-

Latin on altar and wall of cathedral in USA. Understood by few, but seen as holier by some.

-

Sign specifically made for Spanish language church. Burglar alarm warning sign mass-produced, so English.

-

Sign in Jerusalem prohibiting slanderous speech

-

Sign for government-run eye clinic in Yellowknife, Canada, with all 11 official languages of the Northwest Territories

Notes

- ↑ Sebba, Mark (2010). "Review of Linguistic Landscapes: A Comparative Study of Urban Multilingualism in Tokyo.". Writing System Research 2 (1): 73–76. doi:10.1093/wsr/wsp006.

- ↑ Linguistic landscape conference 2015 at Berkeley

- ↑ Tufi, Stefania; Blackwood, Robert (2010). "Trademarks in the linguistic landscape: methodological and theoretical challenges in qualifying brand names in the public space". International Journal of Multilingualism 7 (3): 197–210. doi:10.1080/14790710903568417.

- ↑ Papen, Uta (2012). "Commercial discourses, gentrification and citizens' protest: the linguistic landscape of Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin". Journal of Sociolinguistics 16 (1): 56–80. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2011.00518.x.

- ↑ Heyd, Theresa (2014). "Folk-linguistic landscape". Language in Society 43 (5): 489–514. doi:10.1017/s0047404514000530.

- ↑ Dimitra Karoulla-Vrikki. 2013. Which alphabet on car number-plates in Cyprus? Language Problems and Language Planning 37.3: pp. 249-270

- ↑ Jam Blommaert. 2013. Ethnography, superdiversity, and linguistic landscapes: Chronicles of complexity. Multilingual Matters.

- ↑ Ramamoorthy, L. (2002) Linguistic landscaping and reminiscences of French legacy: The case of Pondicherry. In N.H. Itagy and S.K. Singh (eds) Linguistic Landscaping in India (pp. 118-131). Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages/Mahatma Gandhi International Hindi University.

- ↑ Doris Francis, Georgina Neophytu, Leonie Kellaher. 2005. The Secret Cemetery. Oxford: Berg.

- ↑ p. 42. Kara VanDam. 2009. Dutch- American language shift: evidence from the grave. LACUS Forum XXXIV 33-42.

- ↑ Larissa Aronin and Muiris Ó Laoire. 2012. The material culture of multilingualism. In Durk Gorter, Heiko F. Marten and Luk Van Mensel, eds., Minority Languages in the Linguistic Landscape, pp. 229-318. (Palgrave Studies in Minority Languages and Communities.) Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

References

- Angermeyer, Philipp Sebastian (2005). "Spelling bilingualism: Script choice in Russian American classified ads and signage". Language in Society 34 (4): 493–531. doi:10.1017/s0047404505050190.

- Aronin, Larissa; Laorie, Muiris Ó (2013). "The material culture of multilingualism: moving beyond the linguistic landscape". International Journal of Multilingualism 10 (3): 225–235. doi:10.1080/14790718.2012.679734.

- Backhaus, Peter (2006). "Multilingualism in Tokyo: A Look into the Linguistic Landscape". International Journal of Multilingualism 3 (1): 52–66. doi:10.1080/14790710608668385.

- Backhaus, Peter (2007). "'Linguistic landscapes: a comparative study of urban multilingualism in Tokyo". Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Ben Said, Selim. 2010. Urban Street Signs in the Linguistic Landscape of Tunisia: Tensions in Policy, Representation, and Attitudes. Doctoral dissertation, Pennsylvania State University.

- Bender, Margaret (2008). "Indexicality, voice, and context in the distribution of Cherokee scripts". International Journal of the Sociology of Language 192: 91–104. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2008.037.

- Ben-Rafael, Eliezer; Elana Shohamy; Muhammad Hasan Amara; Nira Trumper-Hecht (2006). "Linguistic Landscape as Symbolic Construction of the Public Space: The Case of Israel". International Journal of Multilingualism 3 (1): 7–30. doi:10.1080/14790710608668383.

- Cenoz, Jasone; Durk Gorter (2006). "Linguistic Landscape and Minority Languages". International Journal of Multilingualism 3 (1): 67–80. doi:10.1080/14790710608668386.

- Choski, Nisshant (2014). "Scripting the border: Script practices and territorial imagination among Santali speakers in eastern India". International Journal of the Sociology of language 227: 47–63. doi:10.1515/ijsl-2013-0087.

- Correll; Arthur Polk, Patrick (2014). "Productos Latinos: Latino business murals, symbolism, and the social enactment of identity in Greater Los Angeles". Journal of American Folklore 127: 285–320. doi:10.5406/jamerfolk.127.505.0285.

- Gorter, Durk (2006). "Introduction: The Study of the Linguistic Landscape as a New Approach to Multilingualism". International Journal of Multilingualism 3 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1080/14790710608668382.

- Gorter, Durk, Heiko F. Marten and Luk Van Mensel, eds. 2012. Minority Languages in the Linguistic Landscape. (Palgrave Studies in Minority Languages and Communities.) Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grivelet, Stéphane (2001). "Digraphia in Mongolia". International Journal of the Sociology of Language 150: 75–94. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2001.037.

- Hassa, Samira (2012). "Regulating and negotiating linguistic diversity: top-down and bottom-up language planning in the Moroccan city". Current Issues in Language Planning: 13 (3): 207–223. doi:10.1080/14664208.2012.722375.

- Kasanga, Luanga Adrien (2012). "Mapping the linguistic landscape of a commercial neighbourhood in Central Phnom Penh". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 32: 1–15. doi:10.1080/01434632.2012.683529.

- Lai, Mee Ling (2013). "The linguistic landscape of Hong Kong after the change of sovereignty". International Journal of Multilingualism 10 (3): 225–235. doi:10.1080/14790718.2012.708036.

- Landry, Rodrigue; Richard Y. Bourhis (1997). "Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality An Empirical Study". Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16 (1): 23–49. doi:10.1177/0261927X970161002.

- Macalister, John (2012). "Language policies, language planning and linguistic landscapes in Timor-Leste". Language Problems and Language Planning 36 (1): 25–45. doi:10.1075/lplp.36.1.02mac.

- Muth, Sebastian (2014). "Linguistic landscapes on the other side of the border: Signs, language, and the construction of cultural identity in Transnistria.". International Journal of the Sociology of language 227: 25–46. doi:10.1515/ijsl-2013-0086.

- Pons Rodríguez, Lola. 2012. El paisaje lingüístico de Sevilla. Lenguas y variedades en el escenario urbano hispalense. Sevilla: Diputación Provincial de Sevilla, Colección Archivo Hispalense. (Download)

- Rasinger, Sebastian M. (2014): Linguistic landscapes in Southern Carinthia (Austria), Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, DOI: 10.1080/01434632.2014.889142

- Sebba, Mark (2010). "Book review: "Linguistic Landscapes: A Comparative Study of Urban Multilingualism in Tokyo", by Peter Backhaus". Writing Systems Research 2 (1): 73–76. doi:10.1093/wsr/wsp006.

- Shiohata, Mariko (2012). "Language use along the urban street in Senegal: perspectives from proprietors of commercial signs". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 33 (3): 269–285. doi:10.1080/01434632.2012.656648.

- Shohamy, Elana; Durk Gorter (2009). Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery. New York and London: Routledge.

- Spolsky, Bernard; Robert Cooper (1991). The Languages of Jerusalem. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

External links

- Bibliography of studies in English on linguistic landscapes

- Linguistic Landscape: An International Journal