Riau-Lingga Sultanate

| Riau-Lingga Sultanate Kesultanan Riau-Lingga كسولتانن رياو-ليڠڬ | |||||

| Dutch protectorate | |||||

| |||||

|

| |||||

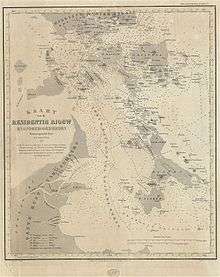

The dominion of Riau-Lingga Sultanate in red, which includes many islands in the South China Sea and portion of lands in mainland Sumatra. | |||||

| Capital | Penyengat Inderasakti (Administrative 1824–1900) (Royal and admistrative 1900–1911) Daik (Royal 1824–1900) | ||||

| Languages | Malay | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||

| Sultan | |||||

| • | 1819–1832 | Abdul Rahman | |||

| • | 1832–1835 | Muhammad II | |||

| • | 1835–1857 | Mahmud IV | |||

| • | 1857–1883 | Sulaiman II | |||

| • | 1885–1911 | Abdul Rahman II | |||

| Yamtuan | |||||

| • | 1805-1831 | Jaafar | |||

| • | 1831-1844 | Abdul | |||

| • | 1844-1857 | Ali II | |||

| • | 1857-1858 | Abdullah | |||

| • | 1858-1899 | Muhammad Yusuf | |||

| Historical era | Dutch Empire | ||||

| • | Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 | 1824 | |||

| • | Abolished by the Dutch | 1911 | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

Riau-Lingga Sultanate (Malay/Indonesian: Kesultanan Riau-Lingga, Jawi: كسولتانن رياو-ليڠڬ), also known as the Lingga-Riau Sultanate, Riau Sultanate or Lingga Sultanate was a Malay sultanate that existed from 1824 to 1911, before being dissolved following the Dutch intervention.

The sultanate was an effect of the partition of the Johor-Riau Sultanate that separated the Peninsular Johor and the island of Singapore from the Riau archipelago after the succession dispute following the death of Mahmud III of Johor, when Abdul Rahman II was crowned as the first Sultan of Riau-Lingga. The maritime kingdom was recognised by both the British and the Dutch following the Anglo-Dutch Treaty in 1824.

History

Background

The Riau Archipelago was a part of the Malaccan Empire since the expansion by Tun Perak in the 15th century, following the earlier regression of the Srivijaya Empire in the region. The axis of regional power then inherited the Johor Sultanate after the fall of Malacca under the hands of Portuguese conquistadors. During the golden age of Johor, the kingdom stretched across half of the Malay Peninsular, eastern Sumatra, Singapore, Bangka, Jambi and the Riau Islands.

It was stated in the Johor Annals of 1849, that on 27 September 1673 the Laksamana (admiral) of Johor, Tun Abdul Jamil was ordered by Abdul Jalil Shah III to open a settlement in Sungai Carang, Ulu Riau, on the Bintan Island. The settlement in Sungai Carang was later known as Riau Lama. Initially a fortress to protect the Johor Empire, the area then prospered into an entrepôt regional trade center that gained prominence in the Strait of Malacca.

Ulu Riau became the capital of Johor during the reign of Sultan Ibrahim when he relocated the capital Batu Sawar, Kota Tinggi in Peninsular Johor to Riau Lama after the old capital was sacked by the Jambi forces on 4 October 1722. Riau Lama then became the capital of the empire for 65 years from 1722 to 1787.[1]

The importance of Lingga began during the crowning of Sultan Mahmud III in 1761. He relocated the capital in Riau Lama, Ulu Riau, Bintan to Daik, Lingga in 1788. The relocation was made as the Sultan believed that he was being reduced to a mere figurehead under the Dutch. He then requested aid from his distant relative, Raja Ismail, a local ruler of Tempasuk to organise a systematic campaign against the Dutch. The campaign proved to be successful. The sultan thanked the perpetrators and rewarded them with gifts.

In fear of retaliation by the Dutch, he organised a mass transfer of the populace: the Sultan left for Lingga with 2000 people, the Bendahara (vizier) to Pahang with 1000 people while others headed to Terengganu. When the Dutch arrived in Riau, there were only a few Chinese planters left, who persuaded the Dutch not to chase the Orang-orang Melayu (Malay people).

The Sultan then developed Lingga and welcomed new settlers to the island, Dato Kaya Megat was appointed as the new Bendahara of Lingga. New dwellings were constructed, roads were built and buildings were improved. He found new unprecedented wealth when tin mines were organised in Singkep. Both the British and Dutch then restored his claim on the Riau island. He began to revive maritime trade as a major source of commodities, especially valuable tin, gambier and spices discreetly with the British.

Origin

In 1812, the Johor-Riau Sultanate suffered a succession crisis. The death of the Mahmud Shah III in Lingga left no heir apparent. During the death of Mahmud Shah III, the eldest prince, Tengku Hussein was in Pahang to celebrate his marriage to the daughter of the Bendahara (governor); however, it was required by royal custom that the successive sultan must with his predecessor at his deathbed.

To further complicate this matter, both of the royal candidates were not full blooded royalties in origin. The mother of Tengku Hussein, Cik Mariam owed her origin to a Balinese slave lady and a Bugis commoner. The other candidate was Tengku Hussein's half-brother, Tengku Abdul Rahman who similarly had a lowborn mother, Cik Halimah. The only unquestionably royal wife and consort of Mahmud Shah was Engku Putri Hamidah, nonetheless her only child died an hour after birth.

In the following chaos, Engku Putri was expected to install Tengku Hussein to be the next sultan, because he had been preferred by the late Mahmud Shah. Based on the royal adat (customary observance), the consent of Engku Puteri was crucial as she was holder of the Cogan (Royal Regalia) of Johor-Riau, by which the installation of the sultan would only be ratified by the presence of the regalia. Nonetheless, Yamtuan Jaafar (then-viceregal of the sultanate) supported the reluctant Tengku Abdul Rahman, adhering to the rules of royal court, as he was present at the late Sultan's deathbed.

Unwilling and furious, the outspoken Queen is then reported to have said, "Who elected Abdul Rahman as sovereign of Johor? Was it my brother Raja Jaafar or by what law of succession has it happened? It is owing to this act of injustice that the ancient empire of Johor is fast falling to decay". The position of the regalia was fundamental to the installation of the sultan; it was a symbol of power, legitimacy and sovereignty of the state. Possession of the regalia was equivalent to the possession of the Johor-Riau Empire.

Owed to the increased political interest penned against the Dutch in the region, the British began to spread their influence and crowned Tengku Hussein in Singapore, bearing the name Hussein Shah of Johor. The British were actively involved in the Johor-Riau administration between 1812–1818, their intervention in Johor-Riau further strengthened their dominance in the Strait of Malacca. They had earlier gained Malacca from the Dutch under Treaty of The Hague in 1795. The British then acknowledged Johor-Riau as a sovereign state and proposed to pay Engku Puteri 50,000 Ringgits (Spanish Coins) for the Royal Regalia, which she refused.

Observing the rapid diplomatic control of the region by the British, the Dutch began to follow the British by crowning Tengku Abdul Rahman as the sultan instead. The Dutch then tried to control the domination of the British by entering the Vienna Treaty in 1818. The Congress of Vienna was perceived to be legitimate by the Dutch, and the recognition of the Johor-Riau sovereignty by the British held to be void. To further curtail the British domination over the region, the Dutch entered into an agreement with the Johor-Riau Sultanate on 27 November 1818. The agreement stipulated that the Dutch shall be the paramount leader of the Johor-Riau Sultanate and only the Dutchman can engage with trade with the kingdom. A Dutch garrison was then stationed in Riau.[2] It was further stipulated that the subsequent appointment of the Johor-Riau Sultan must be consented by the Dutch. The agreement was signed by Yang Dipertuan Muda Raja Jaafar representing Abdul Rahman of Riau without Abdul Rahman's consent or knowledge.

Akin to the mission embarked by the British, both the Dutch and Yamtuan then desperately tried to win the Royal Regalia from Engku Puteri. The reluctant Abdul Rahman, believing he was not the rightful heir to the throne decided to move from Lingga to Terengganu, claiming that he wanted to celebrate his marriage. The Dutch, who desired to control the Johor-Riau Empire, were in fear of losing momentum simply because of an absence of a mere regalia, then informed Timmerman Tyssen, the Dutch Governor of Malacca, to seize Penyengat in October 1822 and removed the Royal Regalia from Tengku Hamidah by force. The regalia was then stored in the Kroonprins (Dutch: Crown Prince's) Fort in Tanjung Pinang. Engku Puteri was then reported to have written a letter to Van Der Capellen, the Dutch Governor in Batavia about this issue. With the Royal Regalia in Dutch hands, Abdul Rahman was invited from Terengganu and proclaimed as the Sultan of Johor, Riau-Lingga and Pahang on 27 November 1822. Hence, the legitimacy of the Johor-Riau Empire is now granted to Abdul Rahman, rather than the British-backed Hussin.

This led to the partition of Johor-Riau under the Anglo-Dutch treaty of 1824, by which the region north of the Singapore Strait including the island of Singapore and Johor were to be under British influence, while the south of the strait along with Riau and Lingga were to be controlled by the Dutch. By installing two sultans from the same kingdom, both the British and the Dutch effectively destroyed the Johor-Riau polity system and satisfied the respective needs of their colonial ambitions.

Under the treaty, Tengku Abdul Rahman was crowned as the Sultan of Riau-Lingga bearing the name of Abdul Rahman of Riau-Lingga, with the royal seat in Daik, Lingga. While Hussein of Johor who was backed by the British was installed as the Sultan of Johore and ruled over Singapore and the Peninsular Johor, he later ceded Singapore to the British in return for their support during the dispute. Both sultans of Johor and Riau acted mainly as puppet monarchs patronised under the guidance of the colonists.

Internal dispute

On 7 October 1857, the Dutch administrators deposed Mahmud IV from his throne for his campaign to throw off both the Dutch and the Yamtuan Hegemony. The Sultan contested that his kingdom was being heavily manipulated by the Dutch and the Yamtuan. He frequently traveled to Singapore, Terengganu and Pahang to gain support and recognition for his power by the British and his circle of kin in other Malay Royal Houses against the viceregal house of Riau that came from Bugis stock. This was also made on the ground that he believed that he was the rightful heir of the preceding Johor-Riau throne over Hussein Shah of Johor.

The act backfired on the Sultan, as his actions were met with suspicion by the British. The British then warned the Dutch that he was in breach of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 by a vassal of the Dutch colonial state. Angered and embarrassed by the Sultan, the Dutch then prohibited him to travel without their consent. Nonetheless, all these prohibitions were ignored by the Sultan.

The crisis reached its peak in 1857, when following the death of the Yamtuan, the Sultan procrastinated to name the Yamtuan's successor. This was due to the fact that the Sultan disagreed with the candidates offered by the Yamtuan's family. The Sultan then tried to name a candidate from Singapore and claimed that the revenues gained by the Yamtuan ought to be paid to him.

The final blow came when he decided to sail to Singapore without settling the issue despite the prohibition of the Dutch. Challenged by the Sultan, the Dutch then deposed him from the throne while he was in Singapore. The Sultan then remained in Singapore and sought to seek for a mediation with the Dutch. The British then decided not to interfere with the issue against the Dutch.

Transition

In Riau, the Dutch and Yamtuan later enthroned his uncle, Badrul Alam Syah II of Riau to be the fourth Sultan of Riau (1857–1883). He was assisted by Yamtuan IX Raja Haji Abdullah (1857–1858). During his reign, Daik was met with unprecedented prosperity. The Sultan improved the local economy by encouraging rice cultivation and opium preparation. He also possessed a small armada to promote trade relations. He introduced sago from the Moluccas to the local people which he believed was a better substitute than rice as a staple food, as rice can be only harvested once yearly. The area then become a regional trade centre attracting traders from China, Celebes, Borneo, Malay Peninsular, Sumatra, Pagaruyung, Java, Siak, Pahang to Daik.

This worried the Dutch, as it was feared that the sultanate could gain enough supplies and forces to defeat them. Due to this fear, the Dutch appointed an assistant resident to be stationed in Tanjung Buton, a port close to Mepar Island, 6 kilometres from the Riau administrative centre.

Nationalism

The globalisation witnessed in the 19th century opened a new opportunity in Riau-Lingga Sultanate. The proximity to the cosmopolitan Singapore located just 40 miles away shaped the political climate of the kingdom. It was an opportunity for the Riau Malays to familiarise themselves with the new ideas in the Middle East. The opening of Suez Canal made it possible that a journey to Mecca via Port Said, Egypt and Singapore would be reduced to a fortnight, thus these cities became major ports for the Hajj pilgrimage, a vital route in the Islamic World where Muslims around the world can gather, meet and exchange various perspectives and views.[3]

Inspired by the experience and intellectual progress attained in the Middle East and influenced by the Pan-Islamism brotherhood, the Riau Malay intelligentsias established Roesidijah (Club) Riouw in 1895. The association was born as a literature circle to develop the religious, cultural and intellectual needs of the sultanate, but as the association matured, it morphed into a more critical organisation and emerged to address the fight against Dutch rule in the kingdom.[4]

The era was marked by the awareness born by the elite and rulers on the importance of watan (homeland) and one's duty towards his or her native soil. In order to succeed to establish a watan, the land is thought to be independent and sovereign, a far-cry from a Dutch-controlled sultanate. Moreover, it is also viewed that the penetration of the west in the state is slowly tearing apart the fabric of the Malay-Muslim identity.

By the dawn of the 20th century, it was obvious that the association was a political tool to rise against the colonist, with Raja Muhammad Thahir and Raja Ali Kelana acting as its backbone. Diplomatic missions were embarked to liberate the kingdom by Raja Ali Kelana accompanied by a renowned Pattani-born Ulema, Syeikh Wan Ahmad Fatani to the Ottoman Empire in 1883, 1895 and in 1905.

The Dutch Colonial Office in Tanjung Pinang then claimed the organisation as versetpartai (Dutch: Left-leaning party). The organisation also won momentous support from the Mohakamah (Malay Judiciary) and the Dewan Kerajaan (Sultanate Administrative Board). The organisation had critically monitored and researched every step that had been taken by the Dutch Colonial Resident pertaining to the sultanate's administration, which led to the outrage of the Dutch.

The movement was an early form of Malay nationalism. Non-violence and passive resistance measures were adopted by the association. The main apparatus of the movement was to hold boycotts as an act of symbolism. The Dutch Colonist then branded the movement as leidelek verset (Dutch: Passive resistance), nonetheless with the passive steps such as ignoring the raising of the Dutch flag was nonetheless met with the anger by the Batavia-based Raad van Indie (Dutch East Indies Council) and the Advisor on Native Affairs, Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje. Based on a eheim (Dutch: secret) letter 660/G, dated 7 May 1904 to the Dutch East Indies Council by Hurgronje, he advocated that the sultanate and association be crushed akin to the earlier Aceh War.

The grounds made by Hurgronje were due to several factors, among which since 1902 the members of Roesidijah Klub would gather around the royal court and they would refuse to raise the Dutch flag on the government vessel. Report was surfaced by the Dutch Colonial Resident in Riau, A.L. Van Hasselt to the Governor of Netherlands East Indies that the Sultan was an opponent to the Dutch and immersed with a group of hardcore verzetparty. Later, on 1 January 1903, the Dutch Colonial Resident found that the Dutch flag was not being raised during his visit to the royal palace. In his report to the governor he wrote; "it seems that he (Abdul Rahman of Riau) acted as if he was a sovereign king and raises his own flag". Based on several records in the Indonesian National Archive, there were some reports that the Sultan then apologised to the governor due to the "flag incident".

In reply by Dutch East Indies Council on eheim letter numbered 1036/G 9 August 1904, the council was indeed agreed on the proposal embarked by Hurgronje and actions were to be taken against the nationalist association. Nonetheless, advice to the Sultan was to be first to put forward a military action towards the kingdom and association. The council then advised the Dutch Resident in Riau to avoid entering contractual agreement before achieving consensus with the ruling elite of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate.

Dissolution by the Dutch

On 18 May 1905, the Dutch made a new agreement with the sultan, among parts of the agreement is to further limit the powers of Riau-Lingga Sultanate, the Dutch flag must be raised higher than the flag of Riau and the Dutch officials shall be given a supreme honour in the land. The agreement further stipulated that the Riau-Lingga Sultanate is a mere achazat (Dutch: loan) from the Dutch Government. The agreement was made due to the fact that the appointment of Abdul Rahman of Riau (1885–1911) was not being made by the consent of the Dutch and he is also clearly against the colonial rule.[5]

The Dutch insisted the sultan to sign the agreement, nonetheless after consenting the fellow rulers of the state Engku Kelana, Raja Ali, Raja Hitam and other members of the ruling elite, the sultan finally refused to sign the agreement. Abdul Rahman II then decided to form a military regiment under the leadership of the regent prince, Tengku Umar. The affiliate of Roesidijah Klub who were mainly the members of the administrative class were seen able to slowly maneuvered Abdul Rahman who was once a supporter of the Dutch rule to act against the colonial desires.

The disagreement then reaches its peak when Raja Ali Kelana, Raja Khalid Hitam and Raja Haji Muhammad Tahir and other members of the ruling class opposed to accept the agreement purposed by the Dutch. The sultan then demonstrated his refusal to cooperate with the Dutch by referring to his ministers without the consent of the Dutch. During the Dutch Resident's visit to Penyengat, the sultan summoned the emirs (local Malay rulers) of Reteh, Gaung and Mandah of which the resident felt that as if he was being besieged by the sultanate.

The bold resolution embarked by the sultan and fellow officials was not welcomed by the Dutch rule. Based on the journal recorded by the Syahbandar (Harbourmaster), the decision of the Sultan was ridiculed by the Dutch Resident, G.F Bruijn Kops who stated "they molded the sultan to retaliate (against the Dutch), hence a retaliation (by the Dutch) he shall be received".

Thus, on the morning of 11 February 1911, the Dutch Naval ships of Java, Tromp and Koetai Torpedo Boat anchored in Penyengat Island deploying hundreds of marechausse (Dutch: pribumi soldiers) to siege the royal court. The event unfolds when the sultan and the court officials were in Daik to perform the Mandi Safar (a ritualistic purifying bath).

This followed by the arrival of Dutch official K.M Voematra to Roesidijah Club headquarter from Tanjung Pinang to renounce the Abdul Rahman II from his throne.[6] On the abdication letter read by Dutch official, he mocked the crown prince and other members of Roesidijah Klub as "sebagai orang berniat bermusuhan dengan Sri Padoeka Gouvenrnement Hindia Nederland" (individuals that harbours animosity against the excellency Governor of Netherlands Indies).

Following the military standoff and political incursion by the Dutch, a mass exodus of the civilians and officials to Johor and Singapore was recorded. The official Regalia and Paraphernalia were then seized Dutch colonial office.[7] In fears of a further seizure by the Dutch, many of the official buildings were deliberately razed by the members of the court themselves.

To avoid violence and the death of civilians in Pulau Penyengat, the Sultan and his officials decided not to fight the Dutch troops. The sultan and Tengku Ampuan (the Queen) left the seat in Pulau Penyengat and sail towards Singapore via the royal vessel Sri Daik, while Crown Prince Raja Ali Kelana, Khalid Hitam and the resistant movement in Bukit Bahjah followed a couple of days later. The Dutch then abdicate the sultan in absentia on 3 February 1911. The deposed Abdul Rahman II was forced to live in exile in Singapore.

Aftermath

The Dutch officially annexed the sultanate to avoid future claims from the monarchy. The Dutch then commenced rechtreek bestuur (Dutch: Direct rule) on the Riau Archipelago in 1913, the province was administered as Residentie Riouw en Onderhoorigheden (Dutch: Residence of Riau and Dependencies) by the Dutch. The Dutch Residence comprises Tanjung Pinang, Lingga, Riau and Indragiri, the Tudjuh Archipelago was being administered separately as "Afdeeling Poelau-Toedjoeh" (Dutch: The Division of Pulau Tudjuh).[8]

The sultan then appealed to the British administration for aid, despite being given an abode and protection in Singapore, the British was quite reluctant to interfere with the Dutch administration. Diplomatic missions were carried to Empire of Japan by Raja Khalid Hitam in 1911 and to the Ottoman Empire by Raja Ali Kelana in 1913 to call for the restoration of the sultanate.[9]

The sultan even at one point wanted to abdicate in favour of his son, Tengku Besar as the negotiation perceived to be in vain. The sultan died in Singapore in 1930. Several members of the royal family later contested their claim to be recognised as the sultan.

Restoration attempt

As the World War II erupted in East Asia, the Dutch was initially seemed to be quite reluctant to defend its territories in the East Indies. This propelled the British to create a buffer state in Riau. They discussed with Tengku Omar and Tengku Besar, the descendants of the sultan who were then based in Terengganu on a prospect for a revival. As the war approaches Southeast Asia, the Dutch actively engaged in the defensive system alongside the British, the British then decided to shelve the restoration plan.[10]

In the aftermath of the war and the struggle against the Dutch rule, several exile associations collectively known as Gerakan Kesultanan Riau (Riau Sultanate Movement) emerged in Singapore and planning for the restoration. Some of the groups dated as early as the heyday of dissolution of the sultanate, nonetheless they started to gain momentum following the post-world war confusion and politics.

Dewan Riouw

Rising from the ashes of political uncertainty and fragility of the East Indies following the World War II, a royalist fraction known as Persatoean Melayu Riouw Sedjati (PMRS) (Association of the Indigenous Riau Malays) emerged to call for the restoration of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate. The council was financially backed by rich Riau Malay émigrés and Chinese merchants who hoped to obtain tin concession. Initially founded in High Street, Singapore, the association moved to Tanjung Pinang, Riau under an unprecedented approval by the Dutch administrators. Based in Tanjung Pinang, the group managed to gain the consent of the Dutch for self-governance in the region with the foundation of Dewan Riouw (Dutch: Riouw Raad, English: Riouw Council), the Riouw Raad is the devolved national, unicameral legislature of Riau, a position equivalent to a Parliament.[11]

After the establishment in Tanjung Pinang, the group later formed a new organisation known as Djawatan Koewasa Pengoeroes Rakjat Riow (The Council of Riau People Administration), with the members hailing from Tudjuh Archipelago, Great Karimun, Lingga and Singkep. This group strongly maintain to restore the sovereignty of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate after the status of Indonesia was solidified.

The group perceived that the position of the Riau Malays were neglected under the expense of the non-Riau Indonesians that have dominated the upper ranks of the Riau civil administration. By restoring the monarch, they believed the position of Riau Malays would be guarded. The leader of the council, Raja Abdullah began to advocate this notion against the newcomers.

The royalist association nonetheless was met with resistance by the republican group led by Dr. Iljas Datuk Batuah that equally sending delegates to Singapore to counter the propaganda of the sultanate supporters. Based on the Indonesian archive, Dr. Iljas gained approvals from the non-Riau newcomers (Minangkabaus, Javanese, Bataknese, Palembagese, Indian, Arabs, among few). He later form a group known as Badan Kedaulatan Indonesia Riouw (BKRI) (Indonesian Riau Sovereign Body) on 8 October 1945. The organisation sought to absorb Riau Archipelago into the then-newly independent Indonesia, as the archipelago was still retained under the Dutch colonial power. BKRI hoped that the new administration under Soekarno will be given a fair chance for the pribumis to run the local government.

The royalist association sought not to publicly exhibit sympathy towards the Indonesian movement, this is by far evident for the refusal of the association to display the Bendera Merah-Putih (Indonesian Flag) during the Indonesian Independence Day celebration on 17 August 1947 in Singapore. Consequently, this led to the republicans to call the royalist as pro-Dutch. The royalist however, maintained that Riau is already a Dutch territory and only the Dutch that can aid with a helping hand.

The claim sought by BKRI was countered by granting an autonomous rule to the Riau Council, where it would exercise maximum autonomy, in which links with the Dutch would be maintained while royalty restoration would play as a secondary role. The inauguration of the council was made on 4 August 1947. The formation of the council was a major step for the resurrection of the monarchy system, several key members of the PMRS were elected to the Riau Council alongside the rivalling BKRI, the Chinese kapitans from Tanjung Pinang and Pulau Tujuh, the local Malay leaders of Lingga and Dutch Officials in Tanjung Pinang. It was formed under the consideration made by the Governor General of East Indies 12 July 1947. Later on 23 January 1948, the states of Bangka Council, the Belitung Council, and the Riau Council are merged as the Bangka Belitung and Riau Federation.

The call for revival of the monarchy system continued to be echoed throughout the autonomous rule under the Dutch-made Riau Council, despite the fact that the influence of republicanism is getting stronger. The appeal began to subside following the dissolution of the Bangka Belitung and Riau Federation on 4 April 1950. The Riau Archipelago was officially incorporated to be an Indonesian regency after the official withdrawal by the Dutch in 1950. The region became Keresidenan Riau under Central Sumatra Province following the absorption by the United States of Indonesia. Being one of the last territories merged into Indonesia, Riau was known as the daerah-daerah pulihan (recovered regions).

The leader of Riau forces, Major Raja Muhammad Yunus who led the bid to reestablish the sultanate apart from Indonesia fled into exile in Johor after his ill attempt. The geopolitical roots of the Riau Archipelago had molded her nationalist position to be sandwiched between the kindred monarchist Peninsular Malay Nationalism observed across the border in British Malaya with the pro-republic and pan-ethnic Indonesian Nationalism manifested in her own Dutch East Indies domain.

Government

In the Riau Sultanate administration, the Sultan acted as the Head of State. While the Dipertuan Muda/Yamtuan Muda (deputy ruler or Viceroy) is a position inherently hold by Bugis ruling elite that functions as the Head of Government. Following the partition of Johor-Riau, the position of the Yamtuan Muda was solely being retained in the Riau-Lingga Sultanate.

The sultan's royal palace was located in Penyengat Inderasakti and the Yamtuan resides in Daik, Lingga. It was perceived that the Malay Sultan shall be dominant in Lingga and its dependencies, while the Bugis Yamtuan would have the control in Riau (consisting Bintan, Penyengat and the surrounding islands), with each respective rulers will not have any claim against the revenues of the other. The sphere of control would only begun to dilute during the time of Yamtuan Yusuf Ahmadi.

Riau later become the heart of Bugis political influence in the western Malay World. It should be noted that however, the power division between the Malay and the Bugis was not met without any major dispute between the two houses.

Adat

The adat istiadat (custom) called for a separation of powers and a pledge of allegiance called Persetiaan Sungai Baru (The Oath of Sungai Baru) sworn between the Bugis and the Malays and renewed for five times between 1722-1858. Under the adat, only the Malays can be the sultan and the position of the Yamtuan reserved exclusively to the Bugis.[12]

The traditional system was retained until the appointment of Abdul Rahman II, the last sultan of Riau-Lingga. Abdul Rahman's father, Raja Muhammad Yusuf, was a Bugis aristocrat and the 10th and the last Yamtuan of Riau. He was married to Tengku Fatimah, the daughter of Sultan Mahmud and was the only full-blooded member of the Malay royalty.

On 17 September 1883, in wake of the death of Badrul Alam Syah II, the Bugis-Malay elites voted for Tengku Fatimah as his successor, becoming the first queen regnant in the history of the empire since the Malaccan period. Nearly a month later, on 13 October another gathering was convened, on this occasion Abdul Rahman II, was crowned as the new sultan after Tengku Fatimah voluntary abdicated in favour of her son.

Conversely, Abdul Rahman II was also first in line of succession to the Yamtuan position. In year 1895, the last of the pledge of allegiance was sworn and made as a final conclusion between the sultan and his father, the last Yamtuan. His father later renounced his position as the Yamtuan. This together mark as a symbol of unity between the Bugis and the Malay dynasties. Thus, solidifying the consolidation of the Sultan and Yamtuan under a single role.[13]

Among the pledge of allegiance stipulated as follows:

| Jawi script | Rumi script | English translation |

|---|---|---|

...جكالاو توان كڤد بوڬيس |

...jikalau tuan kepada Bugis, |

"... if he was an ally to the Bugis |

Yamtuan Muda

The viceregal house of Riau claimed to trace their ancestry from the Bugis Royal House in Luwu, Celebes. The Bugis prominence in the region began during the reign of Abdu'l-Jalil Rahmat of Johor-Riau, during the period of turbulence the Sultan was killed by Raja Kecil who claimed that he was an offspring of the late Sultan Mahmud. He later descent as the Sultan of old Johor. The death of Abdul Jalil was witnessed by his son, Sulaiman of Johor-Riau, who later then requested aid from the Bugis of Klang to combat Raja Kecil and his troops. The alliance formed between Sulaiman and the Bugis managed to defeat Raja Kecil off from his throne.[14]

As the settlement for the debt of honour by Sulaiman of Johor-Riau in 1772, a joint government were structured between the Bugis incomer and the native Malays and several political marriage were formed between the two dynasties. The Bugis chieftain were awarned with the titles of Yang di-Pertuan Muda/Yamtuan Muda (deputy ruler or Viceroy) and Raja Tua (principal prince), receiving the second and third paramount seat in the sultanate. Although the latter title became obsolete, the position of Yamtuan Muda dominated until the reformation that merged the sovereignty of the two Royal houses in 1899.[15]

The Yamtuan possessed a de facto prerogative powers exceeding that of the sultan himself. Despite the fact his function under the law was second highest in the office, nonetheless in practice he can over-ruled the sultan. This is strongly evident during the rule of Abdul Rahman of Riau when Yamtuan Muda Raja Jaafar is perceived to be dominant when he acted as the regent of the sultanate. The Yamtuan Muda Raja Jaafar is responsible for the crowning of Abdul Rahman of Riau and highly influential during the negotiation with the Dutch and English powers during the succession dispute between Tengku Hussein and Tengku Abdul Rahman.

Resident

For the hereditary position of the Sultan, the sultan was fully subjected under the influence of the Dutch East Indies authority. Albeit he is de jure on the apex of the monarchy system, he is under the direct control of the Dutch Resident in Tanjung Pinang. All matters pertaining the administration of the sultanate including the appointment of the sultan and the Yamtuan, must be made within the knowledge and even the consent of the Dutch Resident.

List of office bearers

Sultans of Riau

| Sultans of Johor-Riau | Reign |

|---|---|

| Malacca-Johor Dynasty | |

| Alauddin Riayat Shah II | 1528–1564 |

| Muzaffar Shah II | 1564–1570 |

| Abdul Jalil Shah I | 1570–1571 |

| Ali Jalla Abdul Jalil Shah II | 1571–1597 |

| Alauddin Riayat Shah III | 1597–1615 |

| Abdullah Ma'ayat Shah | 1615–1623 |

| Abdul Jalil Shah III | 1623–1677 |

| Ibrahim Shah | 1677–1685 |

| Mahmud Shah II | 1685–1699 |

| Bendahara Dynasty | |

| Abdul Jalil IV | 1699–1720 |

| Malacca-Johor Dynasty (descent) | |

| Abdul Jalil Rahmat Shah (Raja Kecil) | 1718–1722 |

| Bendahara Dynasty | |

| Sulaiman Badrul Alam Shah | 1722–1760 |

| Abdul Jalil Muazzam Shah | 1760–1761 |

| Ahmad Riayat Shah | 1761 - 1761 |

| Sultan Mahmud Shah III | 1761–1812 |

| Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah | 1812-1832 |

| Muhammad II Muazzam Shah | 1832-1842 |

| Mahmud IV Muzaffar Shah | 1842-1858 |

| Sulaiman II Badrul Alam Shah | 1858-1883 |

| Yamtuan Dynasty | |

| Abdul Rahman II Muazzam Shah | 1883-1911 |

Yang di-Pertuan Muda of Riau

| Yang di-Pertuan Muda of Riau | In office |

|---|---|

| Daeng Marewah | 1722-1728 |

| Daeng Chelak | 1728-1745 |

| Daeng Kemboja | 1745-1777 |

| Raja Haji | 1777-1784 |

| Raja Ali | 1784-1805 |

| Raja Ja'afar | 1805-1831 |

| Raja Abdul Rahman | 1831-1844 |

| Raja Ali bin Raja Jaafar | 1844-1857 |

| Raja Haji Abdullah | 1857-1858 |

| Raja Muhammad Yusuf | 1858-1899 |

National symbol

Flags of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate

The earlier flag of Riau Sultanate was established on 26 November 1818. It was provided in section 11 of the Royal decree that the flag of the Sultanate of Riau shall be black with a white canton. The similar flag design was also adopted in its sister state of Johor.

-

.svg.png)

Flag of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate in 1818.

-

.svg.png)

Personal standard of the Sultan

-

.svg.png)

Personal Standard of the Yamtuan Muda (Viceregal)

-

.svg.png)

Personal standard of the Pangeran Laksamana (Chief Admiral)

-

.svg.png)

Royal Standard

-

.svg.png)

Male Royal Standard

-

Royal Ensign

-

.svg.png)

Yamtuan Ensign

Royal and noble ranks

Royal family

- Sultan: The reigning prince would be styled as Sultan (personal reign name) ibni al-Marhum (father's title and personal name), Sultan of Riau, Lingga and dependencies, with the style of His Highness.

- Tengku Ampuan: The senior consort of the ruling prince.

- Tengku Besar: The Heir Apparent.

- Tengku Besar Perempuan: The consort of the Heir Apparent.

- Tengku Muda: The Heir Presumptive

- Tengku Muda Perempuan: The consort of the Heir Presumptive.

- Tengku: The other sons, daughters and descendants of Sultans, in the male line: They would be styled as Tengku (personal name) ibni al-Marhum (father's title and personal name).

Yamtuan

- Yang di-Pertuan Muda: The ruling prince of Riau, with the style of His Highness. In earlier days, the ruling prince also received the personal title of Sultan and a reign name.

- Raja Muda: The Heir Apparent, styled as Raja (personal name) bin Raja (father's name), Raja Muda.

- Raja: The sons, daughters, grandchildren's and other descendants of the ruling prince, in the male line: Raja (personal name) bin Raja (father's name).

Territory

Following the partition of Johor that relinquish her right over the mainland peninsular, the sultanate was then effectively morphed into a maritime state. The Riau Sultanate's dominion encompass the Riau, Lingga and Tudjuh Archipelago, including Batam, Rempang, Galang, Bintan, Combol, Kundur, Karimun, Bunguran, Lingga, Singkep, Badas, Tambelan, Natuna, Anambas and many smaller islands. There are also several territories in Igal, Gaung, Reteh and Mandah located in Indragiri on mainland Sumatra. All these territories were headed by a Datuk Kaya (nobleman), known as an Amir (equivalent to a Viscount) that had been chosen by the sultan or the ruling elite pertaining to the local administration.

Foreign relations and trade

There are two main economic and commercial sources in Riau-Lingga, spices (especially peppers) and tin. The Dutch had earlier monopolised the trade system in the Riau archipelago even before the partition of 1824. The Dutch was quite enthusiastic to control the region as they had gain the influence following the Dutch-Johor-Riau agreement.[16]

Dutch

One of the most prominent battle during the Riau-Dutch wars was between Raja Haji against the Dutch militia. The fight against the Dutch led by Raja Haji in Tanjung Pinang managed to curtail the Dutch force from advancing to Malacca. In June 1784, Raja Haji was killed in Teluk Ketapang and was posthumously known was "Marhum Teluk Ketapang". After his death in November 1784, the Dutch entered with an agreement with the Johor-Riau Sultanate.

The agreement entered with the Dutch after the death of Raja Ali was perceived to be severely disadvantaged by the Johor-Riau court. The Dutch has forced Mahmud Syah of Johor-Riau to enter the agreement in 1784. The agreement contains 14 clause which was proved to be depriving the powers of the Johor-Riau Sultanate. For instance, the Dutch are free to engaging commerce in the kingdom and can open its own trade post in Tanjung Pinang. Every passing ship in the region must obtain consent from the Dutch and only the Dutch can bring the ores and spices.

British

The Dutch dominance began to wane off when the Dutch East India Company went bankrupt in 1799. The British then started to supersede the influence of the Dutch in the region. In contrast to the Dutch, the British followed a more moderate approach in engaging with the Johor-Riau Empire. Apart from controlling Malacca in 1795, the British recognised the Johor-Riau Sultanate as a sovereign state.

The British were free to engage with commercial activities with the Riau traders without any major economic burden to the Riau traders. The commercial ties between the Johor-Riau sultanate and the British were initially done under secrecy; eventually agreement was being openly practised by both Riau and the British.

Ottoman

Observing the rise of Islamic Brotherhood that gained momentum in the late 18th century, the Riau-Lingga Sultanate regarded the Ottoman Empire as a protector against the non-Muslim colonial powers. In the eyes of the ruling elite of the court, it perceived the Ottomans as a source of inspiration and a balancing power between the western powers and Islamic world. The Crimean War fought by the Ottomans earlier was regarded as a "Muslim power" against the "Foreigners", Christian, which in a degree correlating with the struggle faced in Riau-Lingga.

Seeing the successful Aceh Sultanate gaining a status as a vassal of the Ottoman, it provided a vital precedent for the Riau-Linggas to adhere a similar footsteps following the deteriorating relationship with the Dutch. The court then discussed a possibility to receiving the same status and protection under the Ottomans with the Ottoman consulate-general in Batavia in 1897-1899 Muhammad Kiamil Bey. Diplomatic mission embarked in October 1904 by Raja Ali Kelana with the necessary documents, letter and treaties. In spite so, following the crumbling domestic situation in the Ottoman Empire itself, the Riau case failed to gain any interest by the Ottomans.

Japan

The meteoric rise of Japan as a global superpower by the 19th century was also marveled in awe and hope by the Riau people. Following the demise of the sultanate in 1911, the officials of Riau began to sought help for the restoration of the sultanate. This was in view of the Pan-Asianism movement against the Europeans that began to manifested in southeast Asia.

The members of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate began to appeal for aid and protection. Thus in October 1912, a letter requesting an intervention from the Japanese Emperor was exercised. The letter applied to become a Japanese vassal state together with the restoration of the sultanate, it was signed by the deposed Sultan Abdul Rahman. Raja Khalid Hitam was then delegated to led the diplomatic mission, upon his arrival in Tokyo, he temporary resided with Encik Ahmad, a Penyengat-born Malay academician who taught in Tokyo School of Foreign Languages. Nonetheless, after his arrival in Tokyo, the Dutch Consul-General in Tokyo left the country and heads towards Singapore, resulting the mission to be obsolete.

A second diplomatic mission was then embarked in June 1914 as a final bid, nonetheless the second diplomatic mission was proved to be fatal and vain. Due to the deteriorating health of Raja Khalid Hitam, he died after a brief hospitalisation in Japan.

Society

The opening of Stannary towns in Karimun, Kundur and Singkep by 1801 proved to bring prosperity into the Riau Islands. During this time was when Pulau Penyengat established into a royal settlement in 1804. Initially founded as a royal dowry for Engku Puteri, a Johor-Riau aristrocrat of Bugis lineage who returned to the island from the Mempawah Sultanate in western Borneo. She became the fourth-wife of Sultan Mahmud Syah and Queen Consort of the Johor-Riau Sultanate.

Penyengat was later developed as the seat for the Yamtuan Muda, constructing a palace, balai (audience hall), mosque and fortification on the island, presumably an act to resolve the dispute between the Malays and the Bugis. He expressly promulgated the island to Raja Hamidah and the descendants of Raja Haji (her late father who previously won the war against the Dutch), the sultan then separated his kingdom into a Malay and Bugis sphere. He decided that the Bugis Yamtuans would govern Riau (islands of Bintan, Penyengat and their dependencies) while the Malay Sultan would administer Lingga and its dependencies, with each having no claim with the respective revenues of the other.

Though the island personally belonged to Engku Puteri Hamidah, it was nonetheless being administered by her brother, Raja Jaafar (the Yamtuan) and later by his descendants. Following the division by the sultan, this award an unprecedented opportunity for Raja Jaafar to develop Penyengat as the heart of the kingdom.

Penyengat, situated in the middle of the maritime trade and commercial routes of the Malay World soon become a key Malay literature and cultural centre in the 19th century.[17][18]

Religion

Inspired to elevate the status of Islam to a greater height in Riau-Lingga, Raja Jaafar begun to invite religious clerics and scholars to the palace court. The Islamisation process begun to accelerate during the time of his successor, Raja Ali. Adhering a more strict interpretation of the Quran, Raja Ali began to promulgate Islamic law and custom into the region. During his rule, Naqshbandi gained prominence in Penyengat, with all the princes and court officials are required to study about the religion, Sufism and improved their Quranic recitation. It is also being described by the Dutch that the Bugis Yamtuans and his family as being fanatical Muslims and highly interested in the Islamic studies.

Raja Ali adhered to the view of Al-Ghazali pertaining to the administration, adopting the theory of the bond between a ruler and religion. Reformation also were made within the society, gambling, cockfighting, the mixing of unmarried men and women and the wearing of gold or silk are all being forbidden, while women are required to be veiled. Pirates and evil doers were severely punished and the miscreants would be exiled. The members of the public were all required to perform the five obligatory prayers, with a special dawn watch were also being constituted to ensure the people would rose for the subuh (fajr) prayer. This was continued during the rule of Raja Abdullah, who was equally a devoted member of the Sufi Tariqat.

The role of the imam in Riau-Lingga is perceived to be legitimate concerning the matters of Islamic law, as much as the role of respective sultan and Yamtuan under the pledge of allegiance. The administration adhering to the separation of powers between the imam, the sultan and the ulema, each acting with their own function to create an Islamic state.

Riau was then hailed as the Serambi Mekah (Gateway to Mecca) where the people of Riau would visit Penyengat before embarking on their Hajj pilgrimage to the Muslim holy land. The mosque is the centerpiece of the society, it is not solely confined as a religious centre, but also scholarship, law and administration office. The mosque, located opposite of the Dutch administrative centre of Tanjung Pinang, stood for the strength of the Yamtuans through their devotion to Islam.

Malayness

By the mid 19th century, the Bugis Yamtuans began perceived themselves as the guardian of the quintessential Malay culture, this was in lieu of gradual extinction of the Bugis language and customs within the diaspora community in Riau-Lingga after being largely Malayised under several generations. Several customary practices and ideology did survive however, for instance the revered position of the women in the society and the close affinity kinship based on their common Bugis ancestry and heritage.

A prominent advocate of the Malay culture in Riau-Lingga was Raja Ali Haji, a Bugis-Malay extraction himself. He stressed the responsibility to preserve the Malay culture by the society while the customs of the west and Chinese were not to be duplicated. He further emphasis the attention on the Malay language on how it should not be misappropriate by the European use of the language.

Raja Ali believed that abandoning the Malay tradition would destroy of the order of the world and the Kerajaan (Kingdom), while adopting the western and Chinese dress code would tantamount to the betrayal of Malayness. Raja Ali's view was not seemed to be a forceful compulsion of one's Malayness, but merely an appeal to maintain the tradition in order to achieve the harmony between man and man, man and ruler and man and Allah.

The situation in the other side of the border differs in some extend compared with that of Riau-Lingga Sultanate. Many acts and habits of the rather westernised Malays of Johor and Singapore were frown upon by the officials in Riau.

Roesidijah (Club) Riouw

The progress made during the era also attributed by an intellectual circle known as Roesidijah (Club) Riouw or Rusydiah Klub Riau, formed in 1895. The club was inspired by Jam’iyah al-Fathaniyyah, founded by Malay intelligentsias in Mecca in 1873 by Syekh Ahmad al-Fathani. The association was earlier known as Jam’iyah ar-Rusydiyah, which later renamed itself as Rusydiah Klub Riau and Roesidijah (Club) Riouw.

The name was derived from Arabic word "Roesidijah", meaning intellectuals and "Club" from Dutch which literary translated as a gathering. The influence of Arabic name on the organisation was due to the fact that the members of the group are mainly well-versed in Arab, as Middle eastern countries is a preferred destination for the Malays to further their studies during the era. While the group adopted a Dutch name to illustrate that the association are progressive, open to development and change.

The association was known as the first modern association in the Dutch East Indies. Earlier, the organisation played a major role in supporting intellectuals, artist, writers, poets and philosophers in the Riau-Lingga Sultanate. The aim was to facilitate the development of arts, theatre, live performance and literature. The organisation partake in the major religious celebrations in Riau-Lingga, Isra and Mi'raj, Mawlid, Eid al-Adha, Eid al-Fitr and Nuzul Quran. The association also organised Islamic debates and intellectual discourse, which unsurpisingly that it would morphed as an anti-colonial movement later in its history. The development of the association was being backed by several main sources, sponsorship by the sultanate, Mathba‘at al Ahmadiah (for literature) and Mathba at al Riauwiyah (for government gazettes) publishing houses and the establishment Kutub Kanah Marhum Ahmadi library.[19][20]

Nonetheless, the literature culture witnessed in the Riau-Lingga Sultanate began to stall after 1913, as the Dutch dissolved the monarchy which resulted an exodus of Malay elites and intellectuals departing to Singapore and Johor.

Literature

A prominent leader of the Malay literature in the Riau-Lingga Sultanate is Ali Haji of Riau, born in Selangor and raised in the Royal Court in Penyengat. He was celebrated as a prolific author, poet, historian, legal jurist and a linguist. Some of his works are considered as the Magna opera of the Malay literature, among which are Tuhfat al-Nafis ("the Precious Gift"), Kitab Pengetahuan Bahasa ("Book of Language") — the first dictionary in Malay and Gurindam dua belas ("The Twelve Gurindams"). His works played a vital role in the development of the Malay language. He spends most of his life writing and researching on the Malay language, history, culture and law.

The literary cultivation flourished in Penyengat was also being acknowledged by the Johor delegation during their visit in 1868. The 19th century Riau was marked by various publications of romantic and realist modes of Malay hikayats, pantuns, gurindams, syairs, poetry, historical and literary works by a generation of male and female writers and poets paving the development of Malay literary culture. Literature was not solely seemed to be confined as a source of entertainment, but also a source of mental stimulation and religious solace.

Raja Aisyah's Hikayat Syamsul Anwar completed in 1890 perhaps one earliest testament of feminism that can be witnessed in the Malay literature: it inaugurates the secret life of Badrul Muin, a heroin that disguises herself as a male, the story illustrates that a woman can achieve a same level with a man. While her subsequent work, Syair Khadamuddin decipting the grief of its heroine Sabariah after the death of her husband under the hands of the pirates, it was presumed that the work to be a semi-autobiographical account of herself, following the death of her husband Raja Khalid Hitam in Japan, with pirates being a metaphor of a foreign land.

While Raja Ali Kelana's series of works in Riau-Lingga includes Pohon Perhimpunan Pada Menyatakan Peri Perjalanan (1899) (a narration of his trip to Tudjuh Archipelago between February to March 1896), Perhimpunan Plakat (1900) (a report on his journey to the Middle East) and Kitab Kumpulan Ringkas (1910) (a religious and psychological guidance).[21]

Library

A main figure for the literary culture in Pulau Penyengat was Muhammad Yusof Ahmadi, the 10th Yamtuan of Riau. He was known to be a member of Naqshbandi, a major Sufi Tariqa. He stressed the importance of religion and knowledge with literature. He viewed that a Muslim must be equipped theological wisdom before performing his or her Islamic obligation. Without knowledge, in his view, all the duties as a Muslim will be in vain. He further stressed that knowledge and literature are kindred to one another, literature was born by the thirst of knowledge, while knowledge transfusion was born by literature.[22]

He founded Kutub Khanah Yamtuan Ahmadi in 1866, an Islamic Library, the first of its kind in the Malay world. The collection of the library was bought by Muhammad Yusof from the India, Cairo, Mecca and Medina that cost him 10,000 Ringgits (Spanish Coins). A major abundance of the collection in the library were devoted to the Islamic theological studies. As the library was located at the Penyengat Grand Mosque, the collections were thus readily accessible to the traders, visitors and devotees of the mosque. Following his death, the library was renamed Kutub Khanah Marhum Ahmadi.

Publishing Houses

The printing history in Riau-Lingga begun when the sultanate established a Rumah Cap Kerajaan publishing house in Lingga c. 1885. The printing house published its materials via Lithography technique, with its materials printed in Jawi script and occasionally in Rumi script. Several major works were printed in this house during that period, among which are Muqaddimah fi Intidzam (a critical examination of the duty of the leader to its subjects and religion) in 1886, Tsamarat al-muhimmah (on law, administration of justice and statecraft) in 1886, Undang-Undang Lima Pasal (Code of Laws), Qanun Kerajaan Riau-Lingga (Code of Laws) all written by Raja Ali Haji. In addition to Raja Ali Haji, the publishing house also known to publish the works of Munshi Abdullah, the father of modern Malay literature.

In 1894, Raja Muhammad Yusuf al Ahmadi the 10th Yamtuah founded a publishing house in Penyengat. The publishing house marked with two distinctive prints, it would be stamped as Mathaba'at al Ahmadiah for non-government publications and Mathaba'at al Riauwiyah for official government-related publications.

Mathaba'at al Ahmadiah mainly engaged with general knowledge, Islamic literature and translation works, among which includes Makna Tahyat (Definition of the Tashahhud), Syair Perjalanan Sultan Lingga ke Johor (The journey of Sultan of Lingga to Johore) and Gema Mestika Alam (Echoes of the Universe), among few. While among the works that is known to be published by its cousin publication, the Mathaba'at al Riauwiyah includes Faruk Al-Makmur (the Laws of Riau) and Pohon Perhimpunan (The journey of Raja Ali Kelana to Tudjuh Archipelago).

All the publications in Al Ahmadiah and Riauwiyah were written in Jawi script, the sole exception was Rumah Obat (Medical Journal) by R.H Ahmad, a physician. The journal was written in Rumi on its title in 1894. This mark the increasing influence of Rumi script by the end of the 19th century. Nonetheless, it was perceived by the Riau intellectuals during that period that the Jawi script must be preserved and maintained especially in the matters of religion and culture.

Following the dissolution of the sultanate in 1911, many of the Riau intellectuals headed north to Singapore and Johore. They re-established Mathaba'at al Ahmadiah in Singapore to continue their printing activities, where they would even distribute materials on general knowledge and Islamic literature for free and to act against the Dutch occupation on their homeland. The publishing house was renamed Al-Ahmadiah Press in 1925.[23] [24]

Culture

Apart from being celebrated for its literary contribution, the Riau-Lingga palace court also known for the passion of its musical tradition. Musical performance was rejoiced as a form of entertainment by both the palace and commoners alike. With the coming of the Dutch, the European influence to the musical traditions slowly looms into the court, this is widely consistent with the introduction of instruments in the sultanate such as the violin and tambur from the Western Hemisphere.[25]

The introduction of the Western instruments to the royal court can be traced to the arrival of Raja Jaafar, the Yamtuan of Riau-Lingga. Prior to his installation as the Yamtuan, he was a Klang-based merchant from Selangor that gain prominence because of tin trade. He came to Riau under the invitation of Mahmud III of Johor upon the demise of Raja Aji. Upon his installation, he constructed palace and due to his love for music, he became a pioneer for the western music in the kingdom. Adopting martial music as practised in the west, he sends several young Riau men to Malacca to train from the Dutch on western instruments such as violin, trumpet, flute, among few.

One of the earliest account of the musical tradition of the royal court was made by C. Van Angelbeek, a Dutch official during his visit to Daik, he observed that Tarian Ronggeng (Ronggeng dance) was staged in the palace court, while the suling and rebab were the among favourite of the locals. His report was then published in Batavia in year 1829.

Gamelan Melayu

Among other prominent ensembles of the palace court was the Tarian Gamelan (Malay Gamelan dance), the Malay Gamelan performance is believed to trace its origin from the Johor-Riau palace court as early as the 17th century. It was recorded that an ensemble of Gamelan performance was invited from Pulau Penyengat to Pahang in 1811 in conjunction of the royal wedding between Tengku Hussein of Johor-Riau and Wan Esah, a Pahangite aristocrat.

The dance was performed for the first time in public during the royal wedding in Pekan, Pahang. This mark the birth of Joget Pahang and the spread Tarian Gamelan in the Malay Peninsular.

Mak Yong

The history of Mak Yong, a dance and theatrical performance which had gained prominence in the royal court of Riau-Lingga began in 1780, where two men from Mantang, Encik Awang Keladi and Encik Awang Durte went to Kelantan for their marriage. They returned south and settled in Pulau Tekong (currently located in Singapore) after the marriage. They then told their stories to the locals about their experience witnessing the Mak Yong performance in Kelantan. Enthused by their tale, the people of Pulau Tekong went to Kelantan to learn about the theater performance. Ten years later, the first Mak Yong performance was staged in Riau-Lingga.

The news was then received by Sultan Mahmud Shah III. Attracted by the story, he invited the performers to the palace court. It was not long before Mak Yong become a staple in the dance court of Johor-Riau.[26] Apart from entertainment, the Mak Yong ritual can also act as a mystical healing performance. A main feature that set the Mak Yong Riau aside from Kelantan, in Riau the performance was enhanced by the use of a ceremonial mask, a feature that was nonexistence in Kelantan, the usage of ritual mask closely resembles the Mak Yong performance staged in Pattani and Narathiwat, both located in present-day southern Thailand.

Royal orchestra

The earliest account of Musik Nobat Diraja (Royal Orchestra) was recorded in Sulalatus Salatin (Malay Annals), it was stated that the usage of orchestra performance begun during the reign of the ancient female ruler of Bintan, Wan Seri Bini, also known as Queen Sakidar Syah who claimed to had traveled to Banua Syam (Levant). The Nobat was used during the coronation of Sang Nila Utama, the king of ancient Singapore. The usage of the Nobat was then spread to other Malay Royal Houses in the Malay Peninsular, Samudera Pasai and Brunei.

Between 1722 to 1911, the Nobat played an instrumental toll during the coronation ceremony of the sultan, it was an instrumental component of the royal regalia and a symbol of sovereignty. It can only be played under the order of the sultan in the royal ceremony with a special troupe of performers, known as Orang Kalur or Orang Kalau.

A new Nobat was commissioned for the coronation of Abdul Rahman II in 1885, as it was reported that the Dutch Colonial officer was succumbed into an abdominal pain which it was widely believed caused by supernatural forces. It caused the coronation of Abdul Rahman to be postponed several times as the Dutch Colonial officer would fell into stomach pain each time the old Nobat was playing.

Thus, due to the "supernatural incident", Tengku Embung Fatimah (then Queen mother) ordered that a new Nobat to be made. The new Nobat was donned with Jawi script written Yang Dipertuan Riau dan (and) Lingga Sanah, tahun (year) 1303(AH) (1885AD). The new Nobat was used for the coronation of the sultan in 1885 with the old one never been used again. The old Nobat is now stored in Kadil Private Museum, in Tanjung Pinang while the new one has been inherited to the Royal House of Terengganu.[25]

Royal Brass Band

The western music achieved its prime during the reign of Abdul Rahman of Riau (1881-1911). The genre was better known as cara Hollandia which literary translated as "the Dutch way" genre of music, reflecting its western origin. The seed of western music which begun during the arrival of Raja Jaafar in 1805 matured and become part-and-parcel of the palace institution by the end of the 19th century Riau.

It was during this time where the instrument fully adopted her western counterpart to the purest form, adhering to the composition and instrumental play such as the trumpet, trombone, saxophone, clarinet and European-made drums. Consisting all-Malay members, it was led by Raja Abdulrahman Kecik, the Bentara Kanan (vice-herald) of Riau-Lingga Sultanate.[27]

The brass band began since the 1880s, not long after Abdul Rahman ascended to the throne. The musical assemble formed as an integral part of the official ceremony and the military parade of the palace court. It is also being performed during the royal ball or banquet from the Dutch visit or from other European delegations, usually the invitees from Singapore. The performance played a vital role in the celebration of Crown Prince Yusof upon his reception of the Order of the Netherlands Lion by Wilhelmina of the Netherlands in 1889.

Due to the exclusive nature that is being reserved to the nobility in the sultanate, the performance become extinct alongside with the Royal Orchestra following the dissolution of the sultanate in 1911.

Legacy

The sultanate is widely credited in the development of the Malay and Indonesian language, as various books, literary works and dictionary was contributed in the sultanate. These works formed as the backbone of the modern Indonesian language. Raja Ali Haji, was celebrated for his contribution on the language and honoured as the National Hero of Indonesia in 2004.[28]

See also

- Malay people

- Malayness

- Johor Sultanate

- Selangor Sultanate

- Malacca Sultanate

- Siak Sri Indrapura Sultanate

- Singapura Kingdom

- Srivijaya Kingdom

- Riau Archipelago

- Johor

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

Notes

- ↑ "Dari Sinilah Kejayaan Melayu Riau Bermula" (in Indonesian). Batam: YouTube. 16 December 2013.

- ↑ "Singapore-Johor Sultanate". Countries of the world. December 1989.

- ↑ "Meneroka Peran Cendekiawan Kerajaan Riau-Lingga dalam Menentang Belanda (2)" (in Indonesian). Batam: Batampos.co.id. 4 November 2014.

- ↑ "Verzeparty dan Lydelyk Verzet: Perdirian Roesidijah (Club) Riouw 1890-an -1991" (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang: Tanjungpinangpos.co.id. 2 March 2013.

- ↑ "Sejarah Kerajaan Riau-Lingga Kepulauan Riau" (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang: Balai Pelestarian Nilai Budaya Tanjung Pinang, Ministry of Education and Culture. 8 June 2014.

- ↑ "Meneroka Peran Cendekiawan Kerajaan Riau-Lingga dalam Menentang Belanda (3)" (in Indonesian). Batam: Batampos.co.id. 4 November 2014.

- ↑ "Riau-Lingga dan politik kontrak belanda 1905-1911/" (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang: TanjungPinangPos. 6 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Riau". Amsterdam: Hubert de Vries. 11 November 2010.

- ↑ "Raja Ali Kelana - Ulama pejuang Riau dan Johor" (in Malay). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Utusan Malaysia. 12 July 2004.

- ↑ "Lingga-The Bendahara Dynasty". The Royal Arc.

- ↑ "Gerakan Sultan Riau" (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang: Tanjung Pinang Post. 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Johor dan Kepulauan Riau: Berlainan negara tetapi tetap bersaudara" (PDF) (in Malay). Malaysia: Abdullah Zakaria bin Ghazali.

- ↑ "Silsilah Politik dalam Sejarah Johor-Riau-Lingga-Pahang 1722-1784" (in Malay/Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia: Aswandi Syahri. 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "Malay-Bugis in the Johor-Riau and Riau-Lingga Kingdoms" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia: Dedi Zuraidi. 2012.

- ↑ "Riau-The Vice Regal or Bugis Dynasty". The Royal Arc.

- ↑ "Kesultanan Riau-Lingga" (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Balai Melayu. 2009.

- ↑ "Raja Ali Haji Pencatat Sejarah Nusantara yang Pertama" (in Malay). Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. 1990.

- ↑ "Sejarah Percetakan dan Penerbitan di Riau Abad ke-19-20" (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang: Balai Pelestarian Budaya Tanjung Pinang. 6 June 2014.

- ↑ "Kebudayaan Melayu Riau" (in Indonesian). Indonesia: Pahlevi Annisa.

- ↑ "Naskah Kuno di Riau dan Cendekiawan Melayu" (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Balai Melayu.

- ↑ "Bapak Jurnalistik Indonesia" (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia: Tanjungpinangpos.id. 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Kutub Khanah Marhum Ahmadi, Pustaka Islam Pertama di Asia Tenggara" (in Indonesian). Indonesia: Gunawan Malay. 27 May 2014.

- ↑ "Kemunculan Novel dalam Sastera Moden Indonesia dan Malaysia" (in Malay). Malaysia: A. Wahab Ali. 2014.

- ↑ "Sejarah Percetakan dan Penerbitan di Riau Abad ke-19-20" (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia. 6 June 2014.

- 1 2 "Muzik cara holanda dan istana riau lingga 1805 1911" (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia: Tanjungpinangpos.id. 12 January 2013.

- ↑ "Makyong bernafas di hujung tanduk" (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia: Tanjungpinangpos.id. 21 June 2011.

- ↑ "Muzik cara holanda dan istana riau lingga 1805 1911" (in Indonesian). Tanjung Pinang, Indonesia: Tanjungpinangpos.id. 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Raja Ali Haji" (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Balai Melayu.

Bibliography

- Barbara Watson Andaya (2003) Gender, Islam and the Bugis Diaspora in Nineteenth and Twentieth-Century Riau, Kuala Lumpur:National University of Malaysia, online edition

- Vivienne Wee (2002) Ethno-nationalism in process: ethnicity, atavism and indigenism in Riau, Indonesia, The Pacific Review, online edition

- Mun Cheong Yong (2004) The Indonesian Revolution and the Singapore Connection, 1945-1949, Singapore: KITLV Press, ISBN 9067182060

- Derek Heng, Syed Muhd Khirudin Aljunied (ed.) (2009) Reframing Singapore: Memory, Identity, Trans-regionalism, Singapore: Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 9789089640949

- Virginia, Matheson (1989) Pulau Penyengat : Nineteenth Century Islamic Centre of Riau, online edition

- Barbara Watson Andaya (1977) From Rūm to Tokyo: The Search for Anticolonial Allies by the Rulers of Riau, 1899-1914, online edition