Linearity

In common usage, linearity refers to a mathematical relationship or function that can be graphically represented as a straight line, as in two quantities that are directly proportional to each other, such as voltage and current in an RLC circuit, or the mass and weight of an object.

Example

A crude but simple example of this concept can be observed in the volume control of an audio amplifier. While our ears may (roughly) perceive a relatively even gradation of volume as the control goes from 1 to 10, the electrical power consumed in the speaker is rising geometrically with each numerical increment. The "loudness" is proportional to the volume number (a linear relationship), while the wattage is doubling with every unit increase (a non-linear, exponential relationship).

In mathematics

In mathematics, a linear map or linear function f(x) is a function that satisfies the following two properties:[1]

- Additivity: f(x + y) = f(x) + f(y).

- Homogeneity of degree 1: f(αx) = αf(x) for all α.

The homogeneity and additivity properties together are called the superposition principle. It can be shown that additivity implies homogeneity in all cases where α is rational; this is done by proving the case where α is a natural number by mathematical induction and then extending the result to arbitrary rational numbers. If f is assumed to be continuous as well, then this can be extended to show homogeneity for any real number α, using the fact that rationals form a dense subset of the reals.

In this definition, x is not necessarily a real number, but can in general be a member of any vector space. A more specific definition of linear function, not coinciding with the definition of linear map, is used in elementary mathematics.

The concept of linearity can be extended to linear operators. Important examples of linear operators include the derivative considered as a differential operator, and many constructed from it, such as del and the Laplacian. When a differential equation can be expressed in linear form, it is generally straightforward to solve by breaking the equation up into smaller pieces, solving each of those pieces, and summing the solutions.

Linear algebra is the branch of mathematics concerned with the study of vectors, vector spaces (also called linear spaces), linear transformations (also called linear maps), and systems of linear equations.

The word linear comes from the Latin word linearis, which means pertaining to or resembling a line. For a description of linear and nonlinear equations, see linear equation. Nonlinear equations and functions are of interest to physicists and mathematicians because they can be used to represent many natural phenomena, including chaos.

Linear polynomials

In a different usage to the above definition, a polynomial of degree 1 is said to be linear, because the graph of a function of that form is a line.[2]

Over the reals, a linear equation is one of the forms:

where m is often called the slope or gradient; b the y-intercept, which gives the point of intersection between the graph of the function and the y-axis.

Note that this usage of the term linear is not the same as the above, because linear polynomials over the real numbers do not in general satisfy either additivity or homogeneity. In fact, they do so if and only if b = 0. Hence, if b ≠ 0, the function is often called an affine function (see in greater generality affine transformation).

Boolean functions

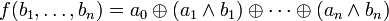

In Boolean algebra, a linear function is a function  for which there exist

for which there exist  such that

such that

, where

, where

A Boolean function is linear if one of the following holds for the function's truth table:

- In every row in which the truth value of the function is 'T', there are an odd number of 'T's assigned to the arguments and in every row in which the function is 'F' there is an even number of 'T's assigned to arguments. Specifically, f('F', 'F', ..., 'F') = 'F', and these functions correspond to linear maps over the Boolean vector space.

- In every row in which the value of the function is 'T', there is an even number of 'T's assigned to the arguments of the function; and in every row in which the truth value of the function is 'F', there are an odd number of 'T's assigned to arguments. In this case, f('F', 'F', ..., 'F') = 'T'.

Another way to express this is that each variable always makes a difference in the truth-value of the operation or it never makes a difference.

Negation, Logical biconditional, exclusive or, tautology, and contradiction are linear functions.

Physics

In physics, linearity is a property of the differential equations governing many systems; for instance, the Maxwell equations or the diffusion equation.[3]

Linearity of a differential equation means that if two functions f and g are solutions of the equation, then any linear combination af + bg is, too.

Electronics

In electronics, the linear operating region of a device, for example a transistor, is where a dependent variable (such as the transistor collector current) is directly proportional to an independent variable (such as the base current). This ensures that an analog output is an accurate representation of an input, typically with higher amplitude (amplified). A typical example of linear equipment is a high fidelity audio amplifier, which must amplify a signal without changing its waveform. Others are linear filters, linear regulators, and linear amplifiers in general.

In most scientific and technological, as distinct from mathematical, applications, something may be described as linear if the characteristic is approximately but not exactly a straight line; and linearity may be valid only within a certain operating region—for example, a high-fidelity amplifier may distort a small signal, but sufficiently little to be acceptable (acceptable but imperfect linearity); and may distort very badly if the input exceeds a certain value, taking it away from the approximately linear part of the transfer function.[4]

Integral linearity

For an electronic device (or other physical device) that converts a quantity to another quantity, Bertram S. Kolts writes:[5][6]

There are three basic definitions for integral linearity in common use: independent linearity, zero-based linearity, and terminal, or end-point, linearity. In each case, linearity defines how well the device's actual performance across a specified operating range approximates a straight line. Linearity is usually measured in terms of a deviation, or non-linearity, from an ideal straight line and it is typically expressed in terms of percent of full scale, or in ppm (parts per million) of full scale. Typically, the straight line is obtained by performing a least-squares fit of the data. The three definitions vary in the manner in which the straight line is positioned relative to the actual device's performance. Also, all three of these definitions ignore any gain, or offset errors that may be present in the actual device's performance characteristics.Many times a device's specifications will simply refer to linearity, with no other explanation as to which type of linearity is intended. In cases where a specification is expressed simply as linearity, it is assumed to imply independent linearity.

Independent linearity is probably the most commonly used linearity definition and is often found in the specifications for DMMs and ADCs, as well as devices like potentiometers. Independent linearity is defined as the maximum deviation of actual performance relative to a straight line, located such that it minimizes the maximum deviation. In that case there are no constraints placed upon the positioning of the straight line and it may be wherever necessary to minimize the deviations between it and the device's actual performance characteristic.

Zero-based linearity forces the lower range value of the straight line to be equal to the actual lower range value of the device's characteristic, but it does allow the line to be rotated to minimize the maximum deviation. In this case, since the positioning of the straight line is constrained by the requirement that the lower range values of the line and the device's characteristic be coincident, the non-linearity based on this definition will generally be larger than for independent linearity.

For terminal linearity, there is no flexibility allowed in the placement of the straight line in order to minimize the deviations. The straight line must be located such that each of its end-points coincides with the device's actual upper and lower range values. This means that the non-linearity measured by this definition will typically be larger than that measured by the independent, or the zero-based linearity definitions. This definition of linearity is often associated with ADCs, DACs and various sensors.

A fourth linearity definition, absolute linearity, is sometimes also encountered. Absolute linearity is a variation of terminal linearity, in that it allows no flexibility in the placement of the straight line, however in this case the gain and offset errors of the actual device are included in the linearity measurement, making this the most difficult measure of a device's performance. For absolute linearity the end points of the straight line are defined by the ideal upper and lower range values for the device, rather than the actual values. The linearity error in this instance is the maximum deviation of the actual device's performance from ideal.

Military tactical formations

In military tactical formations, "linear formations" were adapted from phalanx-like formations of pike protected by handgunners towards shallow formations of handgunners protected by progressively fewer pikes. This kind of formation would get thinner until its extreme in the age of Wellington with the 'Thin Red Line'. It would eventually be replaced by skirmish order at the time of the invention of the breech-loading rifle that allowed soldiers to move and fire independently of the large-scale formations and fight in small, mobile units.

Art

Linear is one of the five categories proposed by Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin to distinguish "Classic", or Renaissance art, from the Baroque. According to Wölfflin, painters of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries (Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael or Albrecht Dürer) are more linear than "painterly" Baroque painters of the seventeenth century (Peter Paul Rubens, Rembrandt, and Velázquez) because they primarily use outline to create shape.[7] Linearity in art can also be referenced in digital art. For example, hypertext fiction can be an example of nonlinear narrative, but there are also websites designed to go in a specified, organized manner, following a linear path.

Music

In music the linear aspect is succession, either intervals or melody, as opposed to simultaneity or the vertical aspect.

Measurement

In measurement, the term "linear foot" refers to the number of feet in a straight line of material (such as lumber or fabric) generally without regard to the width. It is sometimes incorrectly referred to as "lineal feet"; however, "lineal" is typically reserved for usage when referring to ancestry or heredity. The words "linear" & "lineal" both descend from the same root meaning, the Latin word for line, which is "linea".

See also

- Linear actuator

- Linear element

- Linear system

- Linear medium

- Linear programming

- Linear differential equation

- Bilinear

- Multilinear

- Linear motor

- Linear A and Linear B scripts.

- Linear interpolation

References

- ↑ Edwards, Harold M. (1995). Linear Algebra. Springer. p. 78. ISBN 9780817637316.

- ↑ Stewart, James (2008). Calculus: Early Transcendentals, 6th ed., Brooks Cole Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-01166-8, Section 1.2

- ↑ Evans, Lawrence C. (2010) [1998], Partial differential equations (PDF), Graduate Studies in Mathematics 19 (2nd ed.), Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-4974-3, MR 2597943

- ↑ Whitaker, Jerry C. (2002). The RF transmission systems handbook. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0973-1.

- ↑ Kolts, Bertram S. (2005). "Understanding Linearity and Monotonicity" (PDF). analogZONE. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 4, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ↑ Kolts, Bertram S. (2005). "Understanding Linearity and Monotonicity". Foreign Electronic Measurement Technology 24 (5): 30–31. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ↑ Wölfflin, Heinrich (1950). Hottinger, M.D., ed. Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Development of Style in Later Art. New York: Dover. pp. 18–72.

External links

The dictionary definition of linearity at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of linearity at Wiktionary