Linearised polynomial

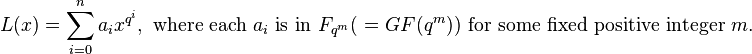

In mathematics, a linearised polynomial (or q- polynomial) is a polynomial for which the exponents of all the constituent monomials are powers of q and the coefficients come from some extension field of the finite field of order q.

We write a typical example as

This special class of polynomials is important from both a theoretical and an applications viewpoint.[1] The highly structured nature of their roots makes these roots easy to determine.

Properties

- The map x → L(x) is a linear map over any field containing Fq

- The set of roots of L is an Fq-vector space and is closed under the q-Frobenius map

- Conversely, if U is any Fq-linear subspace of some finite field containing Fq, then the polynomial that vanishes exactly on U is a linearised polynomial.

- The set of linearised polynomials over a given field is closed under addition and composition of polynomials.

- If L is a nonzero linearised polynomial over

with all of its roots lying in the field

with all of its roots lying in the field  an extension field of

an extension field of  , then each root of L has the same multiplicity, which is either 1, or a positive power of q.[2]

, then each root of L has the same multiplicity, which is either 1, or a positive power of q.[2]

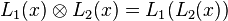

Symbolic multiplication

In general, the product of two linearised polynomials will not be a linearized polynomial, but since the composition of two linearised polynomials results in a linearised polynomial, composition may be used as a replacement for multiplication and, for this reason, composition is often called symbolic multiplication in this setting. Notationally, if L1(x) and L2(x) are linearised polynomials we define

when this point of view is being taken.

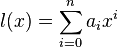

Associated polynomials

The polynomials L(x) and

are q - associates (note: the exponents "qi " of L(x) have been replaced by "i" in l(x)). More specifically, l(x} is called the conventional q-associate of L(x), and L(x) is the linearised q-associate of l(x).

q-polynomials over Fq

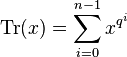

Linearised polynomials with coefficients in Fq have additional properties which make it possible to define symbolic division, symbolic reducibility and symbolic factorizaton. Two important examples of this type of linearised polynomial are the Frobenius automorphism  and the trace function

and the trace function  .

.

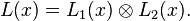

In this special case it can be shown that, as an operation, symbolic multiplication is commutative, associative and distributes over ordinary addition.[3] Also, in this special case, we can define the operation of symbolic division. If L(x) and L1(x) are linearised polynomials over Fq, we say that L1(x) symbolically divides L(x) if there exists a linearised polynomial L2(x) over Fq for which:

If L1(x) and L2(x) are linearised polynomials over Fq with conventional q-associates l1(x) and l2(x) respectively, then L1(x) symbolically divides L2(x) if and only if l1(x) divides l2(x).[4] Furthermore, L1(x) divides L2(x) in the ordinary sense in this case.[5]

A linearised polynomial L(x) over Fq of degree > 1 is symbolically irreducible over Fq if the only symbolic decompositions

with Li over Fq are those for which one of the factors has degree 1. Note that a symbolically irreducible polynomial is always reducible in the ordinary sense since any linearised polynomial of degree > 1 has the nontrivial factor x. A linearised polynomial L(x) over Fq is symbolically irreducible if and only if its conventional q-associate l(x) is irreducible over Fq.

Every q-polynomial L(x) over Fq of degree > 1 has a symbolic factorization into symbolically irreducible polynomials over Fq and this factorization is essentially unique (up to rearranging factors and multiplying by nonzero elements of Fq.)

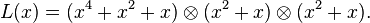

For example,[6] consider the 2-polynomial L(x) = x16 + x8 + x2 + x over F2 and its conventional 2-associate l(x) = x4 + x3 + x + 1. The factorization into irreducibles of l(x) = (x2 + x + 1)(x + 1)2 in F2[x], gives the symbolic factorization

Affine polynomials

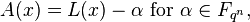

Let L be a linearised polynomial over  . A polynomial of the form

. A polynomial of the form  is an affine polynomial over

is an affine polynomial over  .

.

Theorem: If A is a nonzero affine polynomial over  with all of its roots lying in the field

with all of its roots lying in the field  an extension field of

an extension field of  , then each root of A has the same multiplicity, which is either 1, or a positive power of q.[7]

, then each root of A has the same multiplicity, which is either 1, or a positive power of q.[7]

Notes

- ↑ Lidl & Niederreiter 1983, pg.107 (first edition)

- ↑ Mullen & Panario 2013, p. 23 (2.1.106)

- ↑ Lidl & Niederreiter 1983, pg. 115 (first edition)

- ↑ Lidl & Niederreiter 1983, pg. 115 (first edition) Corollary 3.60

- ↑ Lidl & Neiderreiter 1983, pg. 116 (first edition) Theorem 3.62

- ↑ Lidl & Neiderreiter 1983, pg. 117 (first edition) Example 3.64

- ↑ Mullen & Panario 2013, p. 23 (2.1.109)

References

- Lidl, Rudolf; Niederreiter, Harald (1997). Finite fields. Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications 20 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39231-4. Zbl 0866.11069.

- Mullen, Gary L.; Panario, Daniel (2013), Handbook of Finite Fields, Discrete Mathematics and its Applications, Boca Raton: CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-4398-7378-6