Limes Arabicus

| ||||

| Part of a series on the | ||||

| Military of ancient Rome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural history | ||||

|

||||

| Campaign history | ||||

| Technological history | ||||

|

||||

| Political history | ||||

|

|

||||

| Strategy and tactics | ||||

|

||||

| Military of ancient Rome portal | ||||

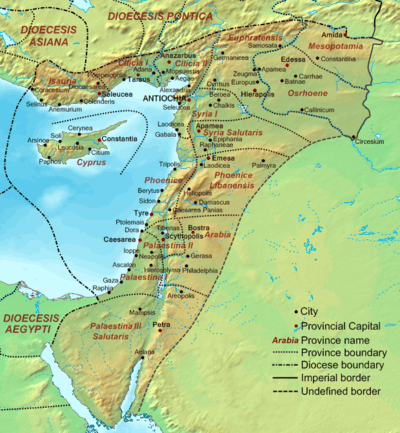

The Limes Arabicus) was a desert frontier of the Roman Empire, mostly in the province of Arabia Petraea. It ran northeast from the Gulf of Aqaba for about 1,500 kilometers (930 mi) at its greatest extent, reaching northern Syria (present-day Rojava) and forming part of the wider Roman limes system. It had several forts and watchtowers.

The reason of this defensive "Limes" was to protect the Roman province of Arabia from attacks of the "barbarian" tribes of the Arabian desert.[1] The main purpose of the Limes Arabicus is disputed; it may have been used both to defend from Saracen raids and to protect the commercial lines from robbers.

Next to the Limes Arabicus Trajan built a major road, the Via Nova Traiana, from Bosra to Aila on the Red Sea in Israel, a distance of 267 miles/430 kilometres. Built between 111 and 114 AD, its primary purpose may have been to provide efficient transportation for troop movements and government officials as well as facilitating and protecting trade caravans emerging from the Arabian peninsula. It was completed under Hadrian.[2]

Fortification

During the Severan dynasty (AD 193–235), the Romans strengthened their defences on the Arabian frontier. They constructed several forts at the northwest end of the Wadi Sirhan, and improved the roads. One important fort was Qasr Azraq, another was at Humeima (Latin: Auara), from the late 2nd C AD, on the Via Nova from Petra to Aila, where up to 500 auxiliary troops could have resided. It was probably abandoned in the fourth century.[3]

Diocletian partitioned the old province of Arabia by transferring the southern region to the province of Palaestina. Later in the 4th century, Palaestina was made into three provinces, and the southern one was eventually called Palaestina Tertia. Each province was administered by a praeses with civil authority and a dux with military authority.

Diocletian engaged in a major military expansion in the region, building a number of castella, watchtowers, and fortresses along the fringe of the desert just east of the Via Nova. This line of defence extended from south of Damascus to Wadi al-Hasa. The region from Wadi Mujib to Wadi al-Hasa contained four castella and a legionary camp. The frontier south of Wadi al-Hasa, which extended to the Red Sea at Aila (Aqaba), may have been called the Limes Palaestina.[4] In this region, ten castella and a legionary camp have been identified. The term may have referred to a series of fortifications and roads in the northern Negev, running from Rafah on the Mediterranean to the Dead Sea,[5] or to the region under the military control of the dux Palaestinae, the military governor of the Palaestinian provinces.[6]

Personnel

There were castra every 100 kilometres (62 mi) with the purpose to create a line of protection and control:[7] in the south there was the legionary fortress at Adrou (Udruh), just east of Petra. It probably housed the Legio VI Ferrata, which was moved from Lajjun (Israel) by Diocletian.[8] It is similar to Betthorus (el-Lejjun in the plain of Moab, south of Wadi Mujib) in size (12 acres (4.9 ha)) and design. Alistair Killick, who excavated the site, dates it to the early 2nd century, but Parker suggests a date in the late 3rd or early 4th century.

A legionary camp may have also existed at Aila (modern Aqaba), which has been excavated by Parker since 1994. The city was located at the north end of the Gulf of Aqaba where it was a centre of sea traffic. Several land routes also intersected here. Legio X Fretensis, originally stationed in Jerusalem, was transferred here to the terminus of the Via Nova. So far, a stone curtain wall and projecting tower have been identified, but it is uncertain whether they were part of the city wall of Aila or the fortress. The evidence suggests the fort was constructed in the late 4th or early 5th century.

Troops were progressively withdrawn from the Limes Arabicus in the first half of the 6th century and replaced with native Arab foederati, chiefly the Ghassanids.[9] After the Arab conquest the Limes Arabicus was left to disappear, but some fortifications were used and reinforced in the following centuries.

See also

References

- ↑ Parker, S. Thomas (1982-07-01). "Preliminary Report on the 1980 Season of the Central "Limes Arabicus" Project". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (247): 1–26. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 1356476. Retrieved 2014-08-25.

- ↑ Young, Gary K. Rome's Eastern Trade: International commerce and imperial policy, 31 BC – AD 305 p. 119

- ↑ Roman castra of Humeima

- ↑ Parker 1986, p. 6

- ↑ Gichon 1991

- ↑ Isaac 1990, pp. 408 – 409

- ↑ Purpose of Roman castra in Arabia

- ↑ Erdkamp, Paul (2008). A Companion to the Roman Army. John Wiley & Sons. p. 253. ISBN 9781405181440.

- ↑ End of Limes Arabicus

Bibliography

- Gichon, Mordechai (1991). "When And Why Did The Romans Commence The Defence of Southern Palestine". In Maxfield, V.A. and Dobson, M. J. Roman Frontier Studies 1989 – Proceedings of the XVth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. pp. 318–325.

- Graf, D. The Via Militaris and the Limes Arabicus in "Roman Frontier Studies 1995": Proceedings of the XVIth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies, ed. W. Groenman-van Waateringe, B. L. van Beek, W. J. H. Willems, and S. L. Wynia. Oxbow Monograph 91. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Gregory, Shelagh, Kennedy, David and Stein, Aurel, Sir Aurel Stein's Limes Report: Part 1 & 2 (British Archaeological Reports (BAR), 1985)

- Gregory, S. Was There an Eastern Origin for the Design of Late Roman Fortifications?: Some Problems for Research on Forts of Rome's Eastern Frontier in "The Roman Army in the East", ed. D. L. Kennedy. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series, 18. Ann Arbor, MI: Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- Isaac, B. The Limits of Empire: The Roman Army in the East Clarendon Press. Oxford, 1990.

- Parker, S.T. (1986). Romans and Saracens: A History of the Arabian Frontier. American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Parker, S. The Roman Frontier in Central Jordan Interim Report on the Limes Arabicus Project, 1980–1985. BAR International Series, 340. British Archaeological Reports. Oxford, 1987

- Young, Gary K. Rome's Eastern Trade: International commerce and imperial policy, 31 BC – AD 305 Routledge. London, 2001

- Welsby, D. Qasr al-Uwainid and Da'ajaniya: Two Roman Military Sites in Jordan Levant 30: 195–8. Oxford, 1990

External links

- Forts of the Limes Arabicus, from Virtual Karak Resources Project

- Qasr Bsshir (Roman castrum)