Nuchal ligament

| Nuchal ligament | |

|---|---|

|

Muscles connecting the arm to the spine seen from behind (nuchal ligament labeled in red at center) | |

| |

| Details | |

| From | External occipital protuberance |

| To | Spinous process of C7 |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Ligamentum nuchae |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | l_09/12492708 |

| TA | A03.2.01.006 |

| FMA | 13427 |

The nuchal ligament is a ligament at the back of the neck that is continuous with the supraspinous ligament.

Structure

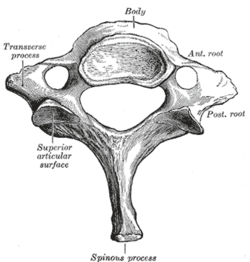

The nuchal ligament extends from the external occipital protuberance on the skull and median nuchal line to the spinous process of the seventh cervical vertebra in the lower part of the neck.[1]

From its anterior border a fibrous lamina is given off, which is attached to the posterior tubercle of the atlas, and to the spinous processes of the cervical vertebrae, and forms a septum between the muscles on either side of the neck.

The trapezius and splenius capitis muscle attach to the nuchal ligament.

In animals

In sheep and cattle it is known as the paddywhack. It relieves the animal of the weight of its head. Dried paddywhack is commonly packaged and sold as a dog treat.

In most other mammals, including the great apes, the nuchal ligament is absent or present only as a thin fascia.[2] As it is required for running, not all animals have one.[3]

All dogs (and all living Canidae - wolves, foxes, and wild dogs) possess a similar ligament connecting the spinous process of their first thoracic (or chest) vertebrae to the back of the axis bone (second cervical or neck bone), which supports the weight of the head without active muscle exertion, thus saving energy.[4] This ligament is analogous in function (but different in exact structural detail) to the nuchal ligament found in ungulates. [4]This ligament allows dogs to carry their heads while running long distances, such as while following scent trails with their nose to the ground, without expending much energy.[4]

Function

In humans it is a tendon-like structure that has developed independently in humans and other animals well adapted for running.[2] In some four legged animals, particularly ungulates, the nuchal ligament serves to sustain the weight of the head.

Additional images

-

Occipital bone seen from outside (nuchal lines are identified at left)

See also

External links

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students (Pbk. ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-443-06612-2.

- 1 2 Swindler, D. R., and C. D. Wood. 1973 An Atlas of Primate Gross Anatomy. Seattle: University of Washington Press

- ↑ Bramble, Dennis M.; Lieberman, Daniel E. (2004). "Endurance running and the evolution of Homo". Nature 432 (7015): 345–52. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..345B. doi:10.1038/nature03052. PMID 15549097.

- 1 2 3 Wang, Xiaoming and Tedford, Richard H. Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008. pp.97-8

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||