Haloform reaction

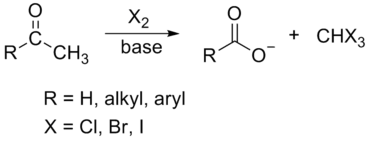

The haloform reaction is a chemical reaction where a haloform (CHX3, where X is a halogen) is produced by the exhaustive halogenation of a methyl ketone (a molecule containing the R–CO–CH3 group) in the presence of a base.[1] R may be alkyl or aryl. The reaction can be used to produce chloroform (CHCl3), bromoform (CHBr3), or iodoform (CHI3).

Scope

Substrates that successfully undergo the haloform reaction are methyl ketones and secondary alcohols oxidizable to methyl ketones, such as isopropanol. The only primary alcohol and aldehyde to undergo this reaction are ethanol and ethanal, respectively. 1,3-Diketones such as acetylacetone also give the haloform reaction. β-ketoacids such as acetoacetic acid will also give the test upon heating. Acetyl chloride and acetamide don't give this test. The halogen used may be chlorine, bromine, or iodine. Fluoroform (CHF3) cannot be prepared from a methyl ketone by the haloform reaction due to the instability of hypofluorite, but compounds of the type RCOCF3 do cleave with base to produce fluoroform; this is equivalent to the second and third steps in the process shown above.

Mechanism

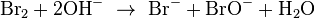

In the first step, the halogen disproportionates in the presence of hydroxide to give the halide and hypohalite (example with bromine, but reaction is the same in case of chlorine and iodine; one should only substitute Br for Cl or I):

If a secondary alcohol is present, it is oxidized to a ketone by the hypohalite:

If a methyl ketone is present, it reacts with the hypohalite in a three-step process:

- (1) Under basic conditions, the ketone undergoes keto-enol tautomerization. The enolate undergoes electrophilic attack by the hypohalite (containing a halogen with a formal +1 charge).

- (2) When the α position has been exhaustively halogenated, the molecule undergoes a nucleophilic acyl substitution by hydroxide, with −CX3 being the leaving group stabilized by three electron-withdrawing groups. In the third step the −CX3 anion abstracts a proton from either the solvent or the carboxylic acid formed in the previous step, and forms the haloform. At least in some cases (chloral hydrate) the reaction may stop and the intermediate product isolated if conditions are acidic and hypohalite is used is used.

animation

Uses

This reaction was traditionally used as a chemical test for qualitative organic analysis to determine the presence of a methyl ketone, or a secondary alcohol oxidizable to a methyl ketone through the iodoform test. Nowadays, spectroscopic techniques such as NMR and infrared are easy and quick to perform instead of qualitative tests. Iodoform reaction is used as test reaction of ethyl alcohol in given sample of alcohols.

It was formerly used to produce iodoform, bromoform, and even chloroform industrially.

In organic chemistry, this reaction may be used to convert a terminal methyl ketone into the analogous carboxylic acid.

Iodoform test

When iodine and sodium hydroxide are used as the reagents, a positive reaction gives iodoform. Iodoform (CHI3) is a pale-yellow substance. Due to its high molar mass caused by the three iodine atoms, it is solid at room temperature (cf. chloroform and bromoform). It is insoluble in water and has an antiseptic smell. A visible precipitate of this compound will form from a sample only when either a methyl ketone, ethanal, ethanol, or a methyl secondary alcohol is present.

History

The haloform reaction is one of the oldest organic reactions known.[2] In 1822, Serullas added potassium metal to a solution of iodine in ethanol and water to form potassium formate and iodoform, called in the language of that time hydroiodide of carbon.[3] In 1831, Justus von Liebig reported the reaction of chloral with calcium hydroxide to form chloroform and calcium formate. The reaction was rediscovered by Adolf Lieben in 1870. The iodoform test is also called the Lieben haloform reaction. A review of the Haloform reaction with a history section was published in 1934.[4]

Net reaction

The net reaction starting from a methyl ketone and hypohalite may be written:

R-CO-CH3 + 3XO- ==> RCOO- + CHX3 + 2OH-

The oxidation of alcohol to a ketone may be written:

R-CHOH-CH3 + XO- ==> R-CO-CH3 + X- + H2O

The net reaction starting from alcohol and hypohalite is therefore:

R-CHOH-CH3 + 4XO- ==> RCOO- + CHX3 + X- + H2O + 2OH-

Note that using hypohalite the alkalinity with not only be maintained but enhanced even though one hydroxide ion is consumed in the final reaction step. Using dihalogen hydroxide ions will instead be consumed in the halogen disproportionation step:

X2 + 2OH- ==> XO- + X- + H2O

Starting from dihalogen the net reactions will be:

R-CO-CH3 + 3X2 + 4OH- ==> RCOO- + CHX3 + 3X- + 3H2O starting from ketone and

R-CHOH-CH3 + 4X2 + 6OH- ==> RCOO- + CHX3 + 5X- + 5H2O starting from alcohol.

Byproducts

The ketone carbon chain will lose its methyl group forming a carboxylate group at the carbonyl position. In the alkaline environment it is expected to be present in ion form. If the ketone is acetone the carboxylate byproduct (RCOO-) would be an acetate ion. Depending on conditions water, hydroxide and halide ions will also form, see net reaction formulas. Note that halide ions form in the dihalogen disproportionation and alcohol oxidation steps, not the haloform reaction per se as is the case for water.

References

- ↑ Chakrabartty, in Trahanovsky, Oxidation in Organic Chemistry, pp 343–370, Academic Press, New York, 1978

- ↑ László Kürti and Barbara Czakó (2005). Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 0-12-429785-4.

- ↑ Georges-Simon Surellas, Notes sur l'Hydriodate de potasse et l'Acide hydriodique. – Hydriodure de carbone; moyen d'obtenir, à l'instant, ce composé triple [Notes on the hydroiodide of potassium and on hydroiodic acid – hydroiodide of carbon; means of obtaining instantly this compound of three elements] (Metz, France: Antoine, 1822). On pages 17–20, Surellas produced iodoform by passing a mixture of iodine vapor and steam over red-hot coals. However, later, on pages 28–29, he produced iodoform by adding potassium metal to a solution of iodine in ethanol (which also contained some water).

- ↑ Reynold C. Fuson and Benton A. Bull (1934). "The Haloform Reaction". Chemical Reviews 15 (3): 275–309. doi:10.1021/cr60052a001.