Lie Kim Hok

| Lie Kim Hok | |

|---|---|

|

Lie, c. 1900 | |

| Born |

1 November 1853 Buitenzorg, Dutch East Indies (modern Bogor, West Java, Indonesia) |

| Died |

6 May 1912 (aged 58) Batavia, Dutch East Indies (modern Jakarta, Indonesia) |

| Cause of death | Typhus |

| Ethnicity | Peranakan Chinese |

| Occupation | Writer, journalist |

| Years active | 1870s–1912 |

| Notable work | |

| Style | Realism |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 4 |

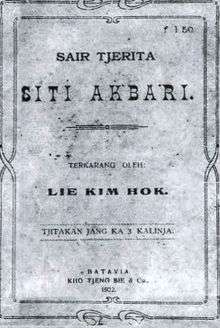

Lie Kim Hok (Chinese: 李金福; pinyin: Lǐ Jīnfú; 1 November 1853 – 6 May 1912) was a peranakan Chinese teacher, writer, and social worker active in the Dutch East Indies and styled the "father of Chinese Malay literature". Born in Buitenzorg (now Bogor), West Java, Lie received his formal education in missionary schools and by the 1870s was fluent in Sundanese, vernacular Malay, and Dutch, though he was unable to understand Chinese. In the mid-1870s he married and began working as the editor of two periodicals published by his teacher and mentor D. J. van der Linden. Lie left the position in 1880. His wife died the following year. Lie published his first books, including the critically acclaimed syair (poem) Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari and grammar book Malajoe Batawi, in 1884. When van der Linden died the following year, Lie purchased the printing press and opened his own company.

Over the following two years Lie published numerous books, including Tjhit Liap Seng, considered the first Chinese Malay novel. He also acquired printing rights for Pembrita Betawi, a newspaper based in Batavia (now Jakarta), and moved to the city. After selling his printing press in 1887, the writer spent three years working in various lines of employment until he found stability in 1890 at a rice mill operated by a friend. The following year he married Tan Sioe Nio, with whom he had four children. Lie published two books in the 1890s and, in 1900, became a founding member of the Chinese organisation Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan, which he left in 1904. Lie focused on his translations and social work for the remainder of his life, until his death from typhus at age 58.

Lie is considered influential to the colony's journalism, linguistics, and literature. According to the Malaysian scholar Ahmad Adam, he is best remembered for his literary works.[1] Several of his writings were printed multiple times, and Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari was adapted for the stage and screen. However, as a result of the language politics in the Indies and independent Indonesia, his work has become marginalised. When several of his writings were revealed as uncredited adaptations of existing works, Lie was criticised as unoriginal. Other critics, however, have found evidence of innovation in his writing style and handling of plots.

Early life

Lie was born in Buitenzorg (now Bogor), West Java, on 1 November 1853, the first child of seven born to Lie Hian Tjouw and his second wife Oey Tjiok Nio. The elder Lie had four children from a previous marriage, with Lie Kim Hok his first child from the new marriage. The well-to-do peranakan Chinese[lower-alpha 1] couple was living in Cianjur at the time but went to Buitenzorg, Lie Hian Tjouw's hometown, for the birth as they had family there. The family soon returned to Cianjur, where Lie Kim Hok was homeschooled in Chinese tradition and the local Sundanese culture and language.[2] By age seven he could haltingly read Sundanese and Malay.[3]

In the mid-19th century the colony's ethnic Chinese population was severely undereducated, unable to enter schools for either Europeans or natives.[4] Aged ten, Lie was enrolled in a Calvinist missionary school run by Christiaan Albers. This school had roughly 60 male students, mostly Chinese.[5] Under Albers, a fluent speaker of Sundanese, he received his formal education in a curriculum which included the sciences, language, and Christianity – the schools were meant to promote Christianity in the Dutch East Indies, and students were required to pray before class.[3] Lie, as with most students, did not convert,[6] although biographer Tio Ie Soei writes that an understanding of Christianity likely affected his world view.[7]

Lie and his family returned to Buitenzorg in 1866. At the time there were no schools offering a European-style education in the city, and thus he was sent to a Chinese-run school. For three years, in which the youth studied under three different headmasters, he was made to repeat traditional Hokkien phrases and copy Chinese characters without understanding them. Tio suggests that Lie obtained little knowledge at the school, and until his death Lie was unable to understand Chinese.[8] During his time in Buitenzorg, he studied painting under Raden Saleh, a friend of his father's. Although he reportedly showed skill, he did not continue the hobby as his mother disapproved. He also showed a propensity for traditional literary forms such as pantun (a form of poetry) and was fond of creating his own.[9]

When Sierk Coolsma opened a missionary school in Buitenzorg on 31 May 1869, Lie was in the first class of ten. Once again studying in Sundanese, he took similar subjects to his time in Cianjur. Around this time he began studying Dutch. After a government-run school opened in 1872, most of Lie's classmates were ethnic Chinese; the Sundanese students, mostly Muslim, had transferred to the new school for fear of being converted to Christianity.[10] In 1873 Coolsma was sent to Sumedang to translate the Bible into Sundanese and was replaced by fellow missionary D. J. van der Linden.[lower-alpha 2] Studies resumed in Malay, as van der Linden was unable to speak Sundanese. Lie and his new headmaster soon became close.[11] The two later worked together at van der Linden's school and publishing house and shared an interest in traditional theatre, including wayang (puppets).[12]

Teacher and publisher

By the age of twenty Lie had a good command of Sundanese and Malay; he also spoke fair Dutch, a rarity for ethnic Chinese at the time.[13] Lie assisted van der Linden at the missionary school, and in the mid-1870s operated a general school for poor Chinese children. He also worked for the missionary's printing press, Zending Press, earning forty gulden a month while serving as editor of two religious magazines, the Dutch-language monthly De Opwekker and the Malay-language bi-weekly Bintang Djohor.[14] He married Oey Pek Nio, seven years his junior, in 1876.[15] Tio, in an interview with the scholar of Chinese Malay literature Claudine Salmon, stated that Lie had been betrothed to Oey's elder sister, but when she ran away the night before the ceremony, he was told to by his parents to marry Oey Pek Nio to save face.[16] Although displeased with the arrangement, he obeyed.[15] The pair soon grew close. The following year they had their first child, although the baby died soon after birth. Lie's mother died in 1879, and his father died the next year.[17]

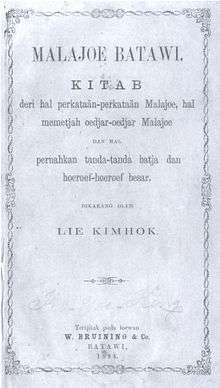

Following these deaths Lie was unable to support his wife. He therefore sold his school to Oey Kim Hoat and left his position at Zending Press to take a job as a land surveyor. In the next four years he held various jobs.[18] In 1881 Oey Pek Nio gave birth again. She died soon afterwards and the baby was sent to live with her grandfather father in Gadog, a village to the southeast of Buitenzorg, to be raised. The child died in 1886.[17] Lie published his first books in 1884. Two of these, Kitab Edja and Sobat Anak-Anak, were published by Zending Press. The former was a study book to help students learn to write Malay, while the latter was a collection of stories for children that Aprinus Salam of Gadjah Mada University credits as the first work of popular literature in the Indies.[19] The other two books were published by W. Bruining & Co., based in the colonial capital at Batavia (now Jakarta). One of these, Malajoe Batawi, was a grammar of Malay intended to standardise the language's spelling.[20] The other was the four-volume syair (a traditional Malay form of poetry) Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari; this book, dealing with a gender-disguised warrior who conquers the Sultanate of Hindustan to save her husband, became one of Lie's best-known works.[21]

After van der Linden's death in 1885, Lie paid his teacher's widow a total of 1,000 gulden to acquire the Zending Press; the funds were, in part, borrowed from his friends.[1] He changed the printer's name to Lie Kim Hok soon afterwards. He devoted most of his time to the publishing house, and it grew quickly, printing works by other authors and reprinting some of Lie's earlier writings. The publishing house was, however, unable to turn a profit.[22] That year he published a new syair, consisting of 24 quartets, entitled Orang Prampoewan.[23] He also wrote opinion pieces in various newspapers, including Bintang Betawi and Domingoe.[24]

The following year Lie purchased publishing rights to the Malay-language newspaper Pembrita Betawi, based in Batavia and edited by W. Meulenhoff, for 1,000 gulden. He again borrowed from his friends. From mid-1886,[lower-alpha 3] Lie's publishing house (which he had moved to Batavia) was credited as the newspaper's printer.[25] While busy with the press, he wrote or contributed to four books. Two were pieces of nonfiction, one a collection of Chinese prophecies and the last outlined lease laws. The third was a partial translation of the One Thousand and One Nights, a collection already popular with Malay audiences. The last was his first novel, Tjhit Liap Seng.[26] Following a group of educated persons in mainland China, Tjhit Liap Seng is credited as the first Chinese Malay novel.[27]

Lie continued to publish novels set in China through 1887, writing five in this period. Several of these stories were based on extant Chinese tales, as retold by his Chinese-speaking friends.[28] The writer sold his shares in Pembrita Betawi to Karsseboom & Co. in 1887, but continued to print the newspaper until it – and Lie's printing press – were acquired by Albrecht & Co. later that year.[29] Lie did not work as a publisher again, although he continued to contribute writings to various newspapers, including Meulenhoff's new publication Hindia Olanda.[25] Over the next three years he did not have fixed employment, taking a multitude of jobs, including bamboo salesman, contractor, and cashier.[30]

Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan, translations, and death

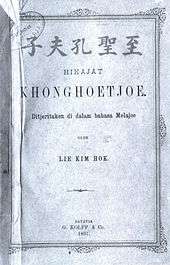

In 1890 Lie began working at a rice mill operated by his friend Tan Wie Siong as a supervisor; this would be his main source of income for the remainder of his life. The following year he married Tan Sioe Nio, twenty years his junior. The new couple had a comfortable life: his salary was adequate, and the work did not consume much energy. To supplement his income Lie returned to translating, Dutch to Malay or vice versa. Sometimes he would translate land deeds or other legal documents. Other times he translated works of literature.[31] This included De Graaf de Monte Cristo, an 1894 translation of Alexandre Dumas' Le Comte de Monte-Cristo, which he completed in collaboration with the Indo journalist F. Wiggers.[26] The two included footnotes to describe aspects of European culture which they deemed difficult for non-European readers to understand.[32] Three years later Lie published Hikajat Kong Hoe Tjoe, a book on the teachings of Confucius.[33] Its contents were derived from European writings on Confucianism and his friends' explanations.[34]

With nineteen other ethnic Chinese, including his former schoolmate Phoa Keng Hek, Lie was an establishing member of the Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan (THHK) school system and social organisation in 1900.[35] Meant to promote ethnic Chinese rights at a time when they were treated as second-class citizens[lower-alpha 4] and provide standardised formal education to ethnic Chinese students where the Dutch had not, the organisation was based on the teachings of Confucius and opened schools for both boys and girls. The THHK grew quickly and expanded into different fields, and Lie helped organise a debating club, sports club, and charity fairs and concerts.[36] From 1903 to 1904 Lie was a managing member of the board, serving mainly as its treasurer.[30]

Lie left the THHK in 1904, although he remained active in social work. Despite increasingly poor health,[7] he wrote opinion pieces for the dailies Sin Po and Perniagaan.[37] He also translated extensively. In 1905 Lie published the first volume of his last Chinese-themed novel, Pembalasan Dendam Hati. This was followed three years later by Kapitein Flamberge, a translation of Paul Saunière's Le Capitaine Belle-Humeur. In the following years he translated several books featuring Pierre Alexis Ponson du Terrail's fictional adventurer Rocambole, beginning with Kawanan Pendjahat in 1910. Two final translations were published in newspapers and collated as novels after Lie's death: Geneviève de Vadans, from a book entitled De Juffrouw van Gezelschap, and Prampoean jang Terdjoewal, from Hugo Hartmann's Dolores, de Verkochte Vrouw. The former translation was completed by the journalist Lauw Giok Lan.[26]

On the night of 2 May 1912 Lie became ill, and two days later his doctor diagnosed him with typhus. His condition steadily declined and on 6 May 1912 he died. He was buried in Kota Bambu, Batavia. THHK schools throughout the city flew their flags at half-mast. Lie was survived by his wife and four children: Soan Nio (born 1892), Hong Nio (born 1896), Kok Hian (born 1898), and Kok Hoei (born 1901). Tan Sioe Nio died the following year.[38]

Legacy

In his journalism career Lie attempted to avoid the yellow press tactics used by his contemporaries[39] and preferred to avoid extensive polemics in the press.[40] Malaysian journalism historian Ahmat Adam, writing in 1995, notes that Lie's entry into the press sparked a wave of peranakan Chinese writers to become newspaper editors,[1] and Sumardjo suggests that Lie remained best known to native Indonesians through his work in the press.[41]

From a linguist's perspective, Kasijanto Sastrodinomo of the University of Indonesia describes Malajoe Batawi as "extraordinary",[lower-alpha 5] noting that the first Malay-language textbook was written by a non-Malay.[42] He also emphasises that the book did not use any English-derived linguistics terms which were omnipresent in 20th-century Indonesian textbooks.[42] Linguist Waruno Mahdi writes that Lie's Malajoe Batawi was the "most remarkable achievement of Chinese Malay writing" from a linguist's point of view.[43] In his doctoral dissertation, Benitez suggests that Lie may have hoped for bazaar Malay to become a lingua franca in the Dutch East Indies.[44] In his history of Chinese Malay literature, Nio Joe Lan finds that Lie, influenced by his missionary education, tried to maintain an orderly use of language in a period where such attention to grammar was uncommon.[45] Nio describes Lie as the "only contemporary peranakan Chinese writer who had studied Malay grammar methodically."[lower-alpha 6][46] Adam considers Lie's works to have left "an indelible mark on the development of modern Indonesian language".[47]

Adam suggests that Lie is best remembered for his contributions to Indonesian literature,[1] with his publications well received by his contemporaries. Tio writes that "old and young intimately read his (Lie's) writings, which were praised for their simple language, rhythm, clarity, freshness, and strength. The skill and accuracy with which he chose his words, the neatness and orderliness with which he arranged his sentences. ... People said that he was ahead of his time. He was likened to a large shining star, a stark contrast to the small, faded stars in the dark sky."[lower-alpha 7][48] Further praise was awarded by other contemporaries, both native and Chinese, such as Ibrahim gelar Marah Soetan and Agus Salim.[49] When ethnic Chinese writers became common in the early 1900s, critics named Lie the "father of Chinese Malay literature" for his contributions, including Siti Akbari and Tjhit Liap Seng.[50]

Several of Lie's books, including Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari, Kitab Edja, Orang Prampoewan, and Sobat Anak-anak, had multiple printings, though Tio does not record any after the 1920s.[26] In 2000 Kitab Edja was reprinted in the inaugural volume of Kesastraan Melayu Tionghoa dan Kebangsaan Indonesia, an anthology of Chinese Malay literature.[51] His Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari, which he considered one of his best works, was adapted for the stage several times. Lie used a simplified version for a troupe of teenaged actors, which was successful in West Java.[52] In 1922 the Sukabumi branch of the Shiong Tih Hui published another stage adaptation under the title Pembalesan Siti Akbari, which was being performed by the theatre troupe Miss Riboet's Orion by 1926.[lower-alpha 8][53] The Wong brothers directed a film entitled Siti Akbari, starring Roekiah and Rd. Mochtar. The 1940 film was purportedly based on Lie's poem, although the extent of the influence is uncertain.[54]

After the rise of the nationalist movement and the Dutch colonial government's efforts to use Balai Pustaka to publish literary works for native consumption, Lie's work began to be marginalised. The Dutch colonial government used Court Malay as a language of administration, a language for everyday dealings that was taught in schools. Court Malay was generally spoken by the nobility in Sumatra, whereas bazaar Malay had developed as a creole for use in trade through much of the Western archipelago; it was thus more common among the lower class. The Indonesian nationalists appropriated Court Malay to help build a national culture, promoted through the press and literature. Chinese Malay literature, written in "low" Malay, was steadily marginalised and declared to be of poor quality.[55] Tio, writing in 1958, found that the younger generation were not learning about Lie and his works,[56] and four years later Nio wrote that bazaar Malay had "made its way to the museums".[lower-alpha 9][57] Literary historian Monique Zaini-Lajoubert indicates that no critical studies of Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari were undertaken between 1939 and 1994.[58]

Controversy

Writing for the Chinese-owned newspaper Lay Po in 1923, Tio revealed that Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari had been heavily influenced by the 1847 poem Sjair Abdoel Moeloek, credited variously to Raja Ali Haji or his sister Saleha. He noted that Sair Siti Akbari, which Lie stated to be his own, closely followed the earlier work's plot.[59] In his 1958 biography, Tio revealed that Lie's Tjhit Liap Seng was an amalgamation of two European novels: Jacob van Lennep's Klaasje Zevenster (1865) and Jules Verne's Les Tribulations d'un Chinois en Chine (1879).[28] Tio noted that a third book, Pembalasan Dendam Hati, had extensive parallels with a work by Xavier de Montépin translated as De Wraak van de Koddebeier.[34] In face of these revelations, literary critics such as Tan Soey Bing and Tan Oen Tjeng wrote that none of Lie's writings were original.[60]

This conclusion has been extensively challenged by writers who have shown original elements in Lie's work. Tio noted that in translating Kapitein Flamberge, Lie had changed the ending: the main character no longer died in an explosion of dynamite, but survived to marry his love interest, Hermine de Morlay.[60] In exploring the similarities between Sjair Abdoel Moeloek and Siti Akbari, Zaini-Lajoubert noted that the main plot elements in both stories are the same, although some are present in one story and not the other – or given more detail. She found that the two differed greatly in their styles, especially Lie's emphasis on description and realism.[61] Salmon wrote that Tjhit Liap Seng's general plot mostly followed that of Klaasje Zevenster, with some sections that seemed to be direct translations. However, she found that Lie also added, subtracted, and modified contents; she noted his more sparse approach to description and the introduction of a new character, Thio Tian, who had lived in Java.[62] The Indonesian literary critic Jakob Sumardjo summarised that Lie "may be said to have been original in his style, but not in his material".[lower-alpha 10][63]

Bibliography

According to Tio, Lie published 25 books and pamphlets; entries here are derived from his list.[26] Salmon writes that some, such as Lok Bouw Tan, may no longer be extant.[64] Lie also wrote some short stories, which are not listed here.[65]

Poetry

- Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari. Batavia: W. Bruining & Co. 1884. (200 pages in 2 volumes)

- Orang Prampoewan. Buitenzorg: Lie Kim Hok. 1885. (4 pages in 1 volume)

Fiction

- Sobat Anak-anak. Buitenzorg: Zending Pers. 1884. (collection of children's stories; 40 pages in 1 volume)

- Tjhit Liap Seng. Batavia: Lie Kim Hok. 1886. (novel; 500 pages in 8 volumes)

- Dji Touw Bie. Batavia: Lie Kim Hok. 1887. (novel; 300 pages in 4 volumes)

- Nio Thian Lay. Batavia: Lie Kim Hok. 1887. (novel; 300 pages in 4 volumes)

- Lok Bouw Tan. Batavia: Lie Kim Hok. 1887. (novel; 350 pages in 5 volumes)

- Ho Kioe Tan. Batavia: Lie Kim Hok. 1887. (novelette; 80 pages in 1 volume)

- Pembalasan Dendam Hati. Batavia: Hoa Siang In Kiok. 1905. (novel; 239 pages in 3 volumes)

Non-fiction

- Kitab Edja. Buitenzorg: Zending Pers. 1884. (38 pages in 1 volume)

- Malajoe Batawi. Batavia: W. Bruining & Co. 1885. (116 pages in 1 volume)

- Aturan Sewa-Menjewa. Batavia: Lie Kim Hok. 1886. (with W. Meulenhoff; 16 pages in 1 volume)

- Pek Hauw Thouw. Batavia: Lie Kim Hok. 1886.

- Hikajat Khonghoetjoe. Batavia: G. Kolff & Co. 1897. (92 pages in 1 volume)

- Dactyloscopie. Batavia: Hoa Siang In Kiok. 1907.

Translation

- 1001 Malam. Batavia: Albrecht & Co. 1887. (at least nights 41 to 94)

- Graaf de Monte Cristo. Batavia: Albrecht & Co. 1894. (with F. Wiggers; at least 10 of the 25 volumes published)

- Kapitein Flamberge. Batavia: Hoa Siang In Kiok. 1910. (560 pages in 7 volumes)

- Kawanan Pendjahat. Batavia: Hoa Siang In Kiok. 1910. (560 pages in 7 volumes)

- Kawanan Bangsat. Batavia: Hoa Siang In Kiok. 1910. (800 pages in 10 volumes)

- Penipoe Besar. Batavia: Hoa Siang In Kiok. 1911. (960 pages in 12 volumes)

- Pembalasan Baccorat. Batavia: Hoa Siang In Kiok. 1912. (960 pages in 12 volumes; posthumous)

- Rocambale Binasa. Batavia: Hoa Siang In Kiok. 1913. (1250 pages in 16 volumes; posthumous)

- Geneviere de Vadana. Batavia: Sin Po. 1913. (with Lauw Giok Lan; 960 pages in 12 volumes; posthumous)

- Prampoewan jang Terdjoeal. Surabaya: Laboret. 1927. (240 pages in 3 volumes; posthumous)

Notes

- ↑ Persons of mixed Chinese and native descent.

- ↑ Sources do not indicate his first name.

- ↑ Tio (1958, p. 55) gives 1 September, a date also cited by Adam (1995, pp. 64–66). However, in a postscript Tio (1958, p. 145) gives the date as 1 June.

- ↑ During this time the Dutch colonial government recognised three groups, each with different rights. Those of highest standing were the Europeans, followed by ethnic Chinese and other "foreign orientals". Native ethnic groups, including the Sundanese and Javanese, were of the lowest standing (Tan 2008, p. 15).

- ↑ Original: "... luar biasa."

- ↑ Original: "... penulis Tionghoa-Peranakan satu2nja pada zaman itu jang telah memperoleh peladjaran ilmu tata-bahasa Melaju setjara metodis."

- ↑ Original: "Tua-muda membatja dengan mesra tulisan2nja, jang dipudji gaja-bahasanja jang sederhana, berirama, djernih, hidup, segar dan kuat. Tjermat dan tepat dipilihnja kata2, tertib dan rapi disusunnja kalimat2. ... Dikatakan orang, ia terlahir mendahului zaman. Ia diibaratkan sebuah bintang besar berkilau-kilauan, suatu kontras tadjam terhadap bintang2 ketjil jang muram diangkasa jang gelap-gelita."

- ↑ This stageplay was reprinted by the Lontar Foundation in 2006 using the Perfected Spelling System.

- ↑ Original: "... sudah beralih kedalam musium."

- ↑ Original: "Boleh dikatakan ia asli dalam gaya tetapi tidak asli dalam bahan yang digarapnya."

References

- 1 2 3 4 Adam 1995, pp. 64–66.

- ↑ Tio 1958, pp. 14–15.

- 1 2 Tio 1958, p. 22.

- ↑ Setiono 2008, pp. 227–231.

- ↑ Suryadinata 1995, pp. 81–82; Setiono 2008, pp. 227–231.

- ↑ Sumardjo 2004, p. 101.

- 1 2 Tio 1958, p. 59.

- ↑ Tio 1958, p. 35.

- ↑ Tio 1958, p. 41.

- ↑ Tio 1958, pp. 32–34, 36.

- ↑ Setyautama & Mihardja 2008, pp. 175–176; Adam 1995, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Setiono 2008, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Setiono 2008, p. 233.

- ↑ Suryadinata 1995, pp. 81–82.

- 1 2 Tio 1958, p. 44.

- ↑ Salmon 1994, p. 141.

- 1 2 Tio 1958, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Tio 1958, p. 58; Suryadinata 1995, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Sumardjo 2004, p. 47; Salam 2002, p. 201.

- ↑ Tio 1958, p. 114.

- ↑ Tio 1958, pp. 46–47; Koster 1998, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Tio 1958, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Tio 1958, p. 125.

- ↑ Tio 1958, p. 51.

- 1 2 Tio 1958, p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tio 1958, pp. 84–86.

- ↑ Salmon 1994, p. 126.

- 1 2 Tio 1958, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Adam 1995, pp. 64–66; Tio 1958, p. 55.

- 1 2 Setyautama & Mihardja 2008, pp. 253–254.

- ↑ Tio 1958, pp. 57–59.

- ↑ Jedamski 2002, p. 30.

- ↑ Adam 1995, p. 73.

- 1 2 Tio 1958, p. 73.

- ↑ Adam 1995, p. 72.

- ↑ Tio 1958, pp. 63–71.

- ↑ Tio 1958, pp. 58–59, 82–83.

- ↑ Setyautama & Mihardja 2008, pp. 253–254; Tio 1958, pp. 58–59, 82–83.

- ↑ Setiono 2008, p. 239.

- ↑ Tio 1958, p. 53.

- ↑ Sumardjo 2004, p. 100.

- 1 2 Sastrodinomo 2009, Teringat akan Lie.

- ↑ Mahdi 2006, p. 95.

- ↑ Benitez 2004, p. 261.

- ↑ Nio 1962, p. 16.

- ↑ Nio 1962, p. 28.

- ↑ Coppel 2013, p. 352.

- ↑ Tio 1958, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Setiono 2008, p. 244.

- ↑ Tio 1958, p. 87.

- ↑ Lie 2000, p. 59.

- ↑ Tio 1958, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Lontar Foundation 2006, p. 155; De Indische Courant 1928, Untitled

- ↑ Filmindonesia.or.id, Siti Akbari; Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad 1940, Cinema: Siti Akbari

- ↑ Benitez 2004, pp. 15–16, 82–83; Sumardjo 2004, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Tio 1958, p. 3.

- ↑ Nio 1962, p. 158.

- ↑ Zaini-Lajoubert 1994, p. 104.

- ↑ Zaini-Lajoubert 1994, p. 103.

- 1 2 Tio 1958, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Zaini-Lajoubert 1994, pp. 109–112.

- ↑ Salmon 1994, pp. 133–139, 141.

- ↑ Sumardjo 2004, p. 99.

- ↑ Salmon 1974, p. 167.

- ↑ Tio 1958, p. 77.

Works cited

- Adam, Ahmat (1995). The Vernacular Press and the Emergence of Modern Indonesian Consciousness (1855–1913). Studies on Southeast Asia 17. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-87727-716-3.

- Benitez, J. Francisco B. (2004). Awit and Syair: Alternative Subjectivities and Multiple Modernities in Nineteenth Century Insular Southeast Asia (Ph.D. thesis). Madison: University of Wisconsin. (subscription required)

- "Cinema: Siti Akbari". Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad (in Dutch) (Batavia: Kolff & Co.). 1 May 1940.

- Coppel, Charles (2013). "Diaspora and Hybridity: Peranakan Chinese Culture in Indonesia". In Tan, Chee-Beng. Routledge Handbook of the Chinese Diaspora. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-60056-9.

- Jedamski, Doris (2002). "Popular Literature and Post-Colonial Subjectivities". In Foulcher, Keith; Day, Tony. Clearing a Space: Postcolonial Readings of Modern Indonesian Literature. Leiden: KITLV Press. pp. 19–48. ISBN 978-90-6718-189-1.

- Koster, G. (1998). "Making it new in 1884; Lie Kim Hok's Syair Siti Akbari". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 154 (1): 95–115. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003906.

- Lie, Kim Hok (2000). "Kitab Edja". In A.S., Marcus; Benedanto, Pax. Kesastraan Melayu Tionghoa dan Kebangsaan Indonesia [Chinese Malay Literature and the Indonesian Nation] (in Indonesian) 1. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. pp. 59–88. ISBN 978-979-9023-37-7.

- Lontar Foundation, ed. (2006). Antologi Drama Indonesia 1895–1930 [Anthology of Indonesian Dramas 1895–1930] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Lontar Foundation. ISBN 978-979-99858-2-8.

- Mahdi, Waruno (2006). "The Beginnings and Reorganization of the Commissie voor de Volkslectuur (1908-1920)". In Schulze, Fritz; Warnk, Holger. Insular Southeast Asia: Linguistic and Cultural Studies in Honour of Bernd Nothofer. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-05477-5.

- Nio, Joe Lan (1962). Sastera Indonesia-Tionghoa [Indonesian-Chinese Literature] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Gunung Agung. OCLC 3094508.

- Salam, Aprinus (2002). "Posisi Fiksi Populer di Indonesia" [Position of Popular Fiction in Indonesia] (PDF). Humaniora (in Indonesian) XIV (2): 201–210.

- Salmon, Claudine (1974). "Aux origines de la littérature sino-malaise: un sjair publicitaire de 1886" [On the Origins of Chinese Malay Literature: A Promotional Sjair from 1886]. Archipel (in French) 8 (8): 155–186. doi:10.3406/arch.1974.1193.

- Salmon, Claudine (1994). "Aux origines du roman malais moderne: Tjhit Liap Seng ou les «Pléiades» de Lie Kim Hok (1886–87)" [On the Origins of the Modern Malay Novel: Tjhit Liap Seng or the 'Pleiades' of Lie Kim Hok (1886–1887)]. Archipel (in French) 48 (48): 125–156. doi:10.3406/arch.1994.3006.

- Sastrodinomo, Kasijanto (16 October 2009). "Teringat akan Lie" [Remembering Lie]. Kompas (in Indonesian). p. 15.

- Setiono, Benny G. (2008). Tionghoa dalam Pusaran Politik [Indonesia's Chinese Community under Political Turmoil] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: TransMedia Pustaka. ISBN 978-979-96887-4-3.

- Setyautama, Sam; Mihardja, Suma (2008). Tokoh-tokoh Etnis Tionghoa di Indonesia [Ethnic Chinese Figures in Indonesia] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Gramedia. ISBN 978-979-9101-25-9.

- "Siti Akbari". filmindonesia.or.id (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Konfiden Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Sumardjo, Jakob (2004). Kesusastraan Melayu Rendah [Low Malay Literature] (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Galang Press. ISBN 978-979-3627-16-8.

- Suryadinata, Leo (1995). Prominent Indonesian Chinese: Biographical Sketches. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-3055-04-9.

- Tan, Mely G. (2008). Etnis Tionghoa di Indonesia: Kumpulan Tulisan [Ethnic Chinese in Indonesia: A Collection of Writings] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia. ISBN 978-979-461-689-5.

- Tio, Ie Soei (1958). Lie Kimhok 1853–1912 (in Indonesian). Bandung: Good Luck. OCLC 1069407.

- "(untitled)". De Indische Courant (in Dutch) (Batavia: Mij tot Expl. van Dagbladen). 19 October 1928.

- Zaini-Lajoubert, Monique (1994). "Le Syair Cerita Siti Akbari de Lie Kim Hok (1884) ou un avatar du Syair Abdul Muluk (1846)" [Syair Cerita Siti Akbari by Lie Kim Hok (1884), or an Adaptation of Syair Abdul Muluk (1846)]. Archipel (in French) 48 (48): 103–124. doi:10.3406/arch.1994.3005.

|