Nuremberg Chronicle

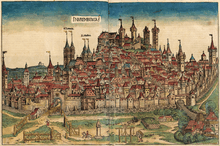

Woodcut of Nuremberg, Nuremberg Chronicle | |

| Author | Hartmann Schedel |

|---|---|

| Original title | Liber Chronicarum |

| Illustrator | Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff |

| Language | Latin; German |

| Subject | History of the world |

| Publisher | Anton Koberger |

Publication date | 1493 |

| Pages | 336 |

The Nuremberg Chronicle is an illustrated biblical paraphrase and world history that follows the story of human history related in the Bible; it includes the histories of a number of important Western cities. Written in Latin by Hartmann Schedel, with a version in German, translation by Georg Alt, it appeared in 1493. It is one of the best-documented early printed books—an incunabulum —and one of the first to successfully integrate illustrations and text.

Latin scholars refer to it as Liber Chronicarum (Book of Chronicles) as this phrase appears in the index introduction of the Latin edition. English speakers have long referred to it as the Nuremberg Chronicle after the city in which it was published. German speakers refer to it as Die Schedelsche Weltchronik (Schedel's World History) in honour of its author.

Production

Two Nuremberg merchants, Sebald Schreyer (1446–1503) and his son-in-law, Sebastian Kammermeister (1446–1520), commissioned the Latin version of the Chronicle. They also commissioned George Alt (1450–1510), a scribe at the Nuremberg treasury, to translate the work into German. Both Latin and German editions were printed by Anton Koberger, in Nuremberg.[1] The contracts were recorded by scribes, bound into volumes, and deposited in the Nuremberg City Archives.[2] The first contract, from December, 1491, established the relationship between the illustrators and the patrons. Wolgemut and Pleydenwurff, the painters, were to provide the layout of the Chronicle, to oversee the production of the woodcuts, and to guard the designs against piracy. The patrons agreed to advance 1000 gulden for paper, printing costs, and the distribution and sale of the book. A second contract, between the patrons and the printer, was executed in March, 1492. It stipulated conditions for acquiring the paper and managing the printing. The blocks and the archetype were to be returned to the patrons once the printing was completed.[3]

The author of the text, Hartmann Schedel, was a medical doctor, humanist and book collector. He earned a doctorate in medicine in Padua in 1466, then settled in Nuremberg to practice medicine and collect books. According to an inventory done in 1498, Schedel's personal library contained 370 manuscripts and 670 printed books. The author used passages from the classical and medieval works in this collection to compose the text of Chronicle. He borrowed most frequently from another humanist chronicle, Supplementum Chronicarum, by Jacob Philip Foresti of Bergamo. It has been estimated that about 90% of the text is pieced together from works on humanities, science, philosophy, and theology, while about 10% of the Chronicle is Schedel’s original composition.[4]

Nuremberg was one of the largest cities in the Holy Roman Empire in the 1490s, with a population of between 45,000 and 50,000. Thirty-five patrician families comprised the City Council. The Council controlled all aspects of printing and craft activities, including the size of each profession and the quality, quantity and type of goods produced. Although dominated by a conservative aristocracy, Nuremberg was a center of northern humanism. Anton Koberger, printer of the Nuremberg Chronicle, printed the first humanist book in Nuremberg in 1472. Sebald Shreyer, one of the patrons of the Chronicle, commissioned paintings from classical mythology for the grand salon of his house. Hartmann Schedel, author of the Chronicle, was an avid collector of both Italian Renaissance and German humanist works. Hieronymus Münzer, who assisted Schedel in writing the Chronicle’s chapter on geography, was among this group, as were Albrecht Dürer and Johann and Willibald Pirckheimer.[2]

Publication

The Chronicle was first published in Latin on 12 July 1493 in the city of Nuremberg. This was quickly followed by a German translation on 23 December 1493. An estimated 1400 to 1500 Latin and 700 to 1000 German copies were published. A document from 1509 records that 539 Latin versions and 60 German versions had not been sold. Approximately 400 Latin and 300 German copies survived into the twenty-first century.[5] The larger illustrations were also sold separately as prints, often hand-coloured in watercolour. Many copies of the book are also coloured, with varying degrees of skill; there were specialist shops for this. The colouring on some examples has been added much later, and some copies have been broken up for sale as decorative prints.

The publisher and printer was Anton Koberger, the godfather of Albrecht Dürer, who in the year of Dürer's birth in 1471 ceased goldsmithing to become a printer and publisher. He quickly became the most successful publisher in Germany, eventually owning 24 printing presses and having many offices in Germany and abroad, from Lyon to Budapest.[6]

Contents

The Chronicle is an illustrated world history, in which the contents are divided into seven ages:

- First age: from creation to the Deluge

- Second age: up to the birth of Abraham

- Third age: up to King David

- Fourth age: up to the Babylonian captivity

- Fifth age: up to the birth of Jesus Christ

- Sixth age: up to the present time (the largest part)

- Seventh age: outlook on the end of the world and the Last Judgment

Illustrations

The large workshop of Michael Wolgemut, then Nuremberg's leading artist in various media, provided the unprecedented 1,809 woodcut illustrations (before duplications are eliminated; see below). Sebastian Kammermeister and Sebald Schreyer financed the printing in a contract dated March 16, 1492, although preparations had been well under way for several years. Wolgemut and his stepson Wilhelm Pleydenwurff were first commissioned to provide the illustrations in 1487-88, and a further contract of December 29, 1491, commissioned manuscript layouts of the text and illustrations.

Albrecht Dürer was an apprentice with Wolgemut from 1486 to 1489, so may well have participated in designing some of the illustrations for the specialist craftsmen (called "formschneider"s) who cut the blocks, onto which the design had been drawn, or a drawing glued. From 1490 to 1494 Dürer was travelling. A drawing by Wolgemut for the elaborate frontispiece, dated 1490, is in the British Museum.

As with other books of the period, many of the woodcuts, showing towns, battles or kings were used more than once in the book, with the text labels merely changed; one count of the number of original woodcuts is 645. The book is large, with a double-page woodcut measuring about 342 x 500mm.[6] Only the city of Nuremberg is given a double page illustration with no text. The illustration for the city of Venice is adapted from a much larger woodcut of 1486 by Erhard Reuwich in the first illustrated printed travel book, the Sanctae Perigrinationes of 1486. This and other sources were used where possible; where no information was available a number of stock images were used, and reused up to eleven times. The view of Florence was adapted from an engraving by Francesco Rosselli.[7]

References

- ↑ Cambridge Digital Library, University of Cambridge, http://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/PR-INC-00000-A-00007-00002-00888/1

- 1 2 WIlson, Adrian. The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle. Amsterdam: A. Asher & Co. 1976

- ↑ Landau, David and Peter Parshall. The Renaissance Print, 1470–1550. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994

- ↑ "About this book - Author", Beloit College Morse Library, 2003

- ↑ "About this book - Latin and German Editions", Beloit College Morse Library

- 1 2 ,Giulia Bartrum, Albrecht Dürer and his Legacy, British Museum Press, 2002, pp. 94-96, ISBN 0-7141-2633-0

- ↑ A Hyatt Mayor, Prints and People, Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, nos 43 & 173.ISBN 0-691-00326-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nuremberg Chronicle. |

| German Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Coloured Latin edition and First English Translation (and comparison) at Beloit College

- Un-coloured (B&W) German language edition at Google Books

- Coloured German language full edition online

- Coloured Latin edition from the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

- The fulltext of the original book published in 1493

.jpg)